Articles/Essays – Volume 24, No. 3

Why Ane Wept: A Family History Fragment

Ane PEdersdatter of Sjaelland, Denmark, entered Bear River Valley in northern Utah much as if she were going to jail. Her granddaughter Elvina told the story long afterwards:

About April 15th [of 1866] Ane left Brigham City. She followed an early trapper’s or Indian trail north along the foothills to the point half way between Honeyville and Deweyville. Then westward, crossing the Bear River at Boise Bend. At this point the Bear River was wide and the bottom was sandstone and not mirey.

Ane beheld the Bear River Valley with sage and Indian trails. She wept bitterly as she camped that night on the west side of the river. The family traveled on. (Jensen 1947, 5)

Later Elvina and her sister-in-law May N. Anderson refined the story for the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers record to make Ane’s tears understandable. Ane (“Ann-eh” in old-style Danish) couldn’t sit by her campfire at the end of her pioneer journey and weep without reason. She couldn’t remain old-fashioned Ane either. She became English-style Anne in their account (“Annie” finally on her tombstone).

On April 10, 1866, they started north and crossed Bear River at Boise Bend. That night Anne became very despondent. She saw the Bear River Valley sunbaked and covered with sage, and wept bitterly. She thought of her home and her royal friends in Denmark, and of the comforts of the life she had left forever. The place where they crossed the river was called Boise Bend Ford. Here a marker has since been placed. (Jensen and Anderson 1966, 74)

Her crossing of the Bear paved the way for my birth fifty-six years later in the valley she had entered, and now sixty-eight additional years have passed. As a wide-eyed boy, I watched my father, Ane’s grandson, dedicate the marker engraved simply “Boise Ford, 1866.” My cousin Bob claims the incised stone still lies there smothered in willows, though the ford itself has washed away. It ought to say, “Ane Pedersdatter crossed here and wept.”

Ane came from Denmark’s main island to Mormon Utah in mid life, a widow with six grown children. The Bear crossing was the last lap of a ten thousand-mile journey by ship, train, and covered wagon (the last making her eligible for the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers record). Despite the explanation by Elvina and May, I can’t immediately understand her bitter tears just as she reached what would be the family’s American home ground. I would think she would have sung joyously with her traveling companions:

O ye mountains high

Where the clear blue sky

Arches over the vales of the free . . .

Now my own mountain home

Unto thee I have come,

All my fond hopes are centered in thee.

Hopeful or not, however, that evening in April at Boise Ford, she cried.

Could she have realized just at that point that Brigham Young’s Zion wasn’t paradise, only sagebrush country? Could she suddenly, deeply, have wanted the Bear River (where Bob and I would later fish and swim) to magically become the Roskilde Fjord by Nordskoven in Sjaelland (where her own boys had learned to fish and swim)? Did it come to her totally just then that her husband Peder, eight years dead, wasn’t with her? I want her real reasons.

Might it have been fear of the wilderness, of the Indian trails she had seen, that suddenly undid her? She and her vulnerable family had some experience with Indian ferocity. Just out of Fort Laramie the previous October, their wagon train had stopped for water and sustained a swift attack. “We had driven the loose stock and our teams up a ravine to a watering place about three-fourths of a mile from camp,” young Anton Nelsen recorded in his journal of their odyssey, “when the Indians came upon us from their hiding places.”[1] A Danish woman younger than Ane was snatched away and never rescued. Bluffs like those in Wyoming confront the river at Boise Ford. Ane could have wept at the Bear fearing a like fate for her or for her only daughter, Christine, who wasn’t even baptized into the Mormon Church yet.

Many times in later years I waded through that ford with carp darting past my legs and now and then an alarmist beaver slapping the water with its tail. It remained a wild place for a long time. Indians riding in from the wilderness didn’t seem beyond possibility even in the 1930s. Once my father’s friend Will Ottogary, a Shoshone, was helping us gather hay in the bend where Ane and her family camped, and Will said with a sweep of his arm, “Some day, Lee, this will be Indian land again.” A chill went through me.

Still, when Ane crossed the ford in 1866, she had three grown sons with her who had helped her cross the sea and the continent. Anders (my grandfather), the eldest, carried the talismanic Henry rifle he’d borne against the Prussians in the Schleswig-Holstein War. He was going on twenty-five when they crossed the ford, Hans was twenty three, and Rasmus twenty. The youngest son, James, who would live to tell a thrilling story of Indian horse thieves on the Montana Trail, had just turned thirteen. Christine was sixteen. (Peter, born between Hans and Rasmus, had been left behind in Hamburg, quarantined for smallpox.) Ane had ample protection. And if plain fear of Indians had caused her tears, would they have been “bitter” tears?

Elvina and May say she wept bitterly when she looked at the valley covered with sage and thought of all she’d left behind in Denmark. Maybe so. There were things she would miss. Ane was a Pedersdatter (both father and husband named Peder) born in 1814 at Skuldelev where Vikings once moored their long boats—north of ancient Roskilde. She married a weaver of Sonderby and then—widowed early—married Peder, my great-grandfather. They settled on a grand farm named Skaaningegaard north of Jaegerspris castle on the Hornsherred peninsula and had seven children. Storks from Egypt settled on the chimneys of farmhouses like theirs each spring.

When Ane reached Utah in November of 1865 (having sold the farm), she sought out an old Skuldelev friend, a Danish dairyman, and his wife who were already settled in Brigham City, one of Brigham Young’s northern outposts. Christian and Elizabeth Hansen took in Ane’s family for five snowy months, until the warm-up of April. Their house was of the timber-frame and stucco type Ane and her children had known in Sjaelland, only here it was adobe walled.

The Brigham house where Ane stayed is still there, like the Boise Ford campground where she wept. The house was remodeled snugly in the Spanish Revival style by a doctor who bought it sixty years later. Its white walls, deep-set windows, and tile roof now give it a modish, dreamy air, but the old, low-built adobe dimensions are still apparent. I stood on the street in front of it recently, picturing Ane arriving here at the end of her ocean and continent-crossing ordeal to find a semblance of soft Sjaelland built in these hard mountains of the West.

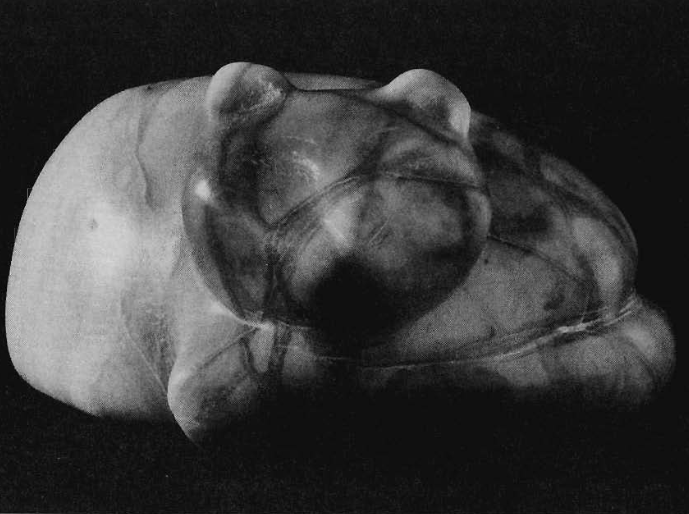

When she confronted raw Bear River Valley in mid-April, the part of Ane accustomed to comfort registered the loss of the warm Danish shelter she’d found in Brigham City. She brought with her to America a few essential mementos of her Sjaelland life—a mantel clock, two turned brass candlesticks, a little cast-iron Danish cookstove, even a fine broad-striped Sjaelland dress in which she had herself photo graphed during the Brigham winter. Elvina records that she received an offer of a house and two city lots in Brigham City for her stove, but “it failed to interest her.” The offer probably came from her friendly host, Christian Hansen, wanting good Danish baking to go with his cheeses. Had she accepted the offer, she could have taken up her American life in the bustling new town.

Brigham City’s surprising springtime warmth encouraged fruit growing, particularly peaches. It would have been a secure, delightful place for Ane to settle. I wish she’d done that. Later I loved bright Brigham with its fat peaches, its red and white tabernacle, and its grand county courthouse. She could have built a proper Danish house there around her clock and candlesticks, with a fireplace like the Hansens’ in place of her stove. Her boys could still have gone on probing the sagebrush and Indian trails and harsh weather.

But she went on with her sons as their leader and accepted the loss of Brigham City.

Perhaps the pang of regret (coupled with wet, cold feet from crossing the ford in April) sharpened Ane’s Sjaelland homesickness. Elvina and May say she wept when she looked out at the Bear River Valley, “sunbaked and covered with sage,” and thought of “her home and her royal friends in Denmark, and of the comforts of life she had left forever.” My memory of the valley compels me to stress that it wasn’t sunbaked in April—this was Elvina and May’s hot summer boredom of later valley years talking. Crusty snow would still have been melting in the shade of sagebrush when Ane crossed the ford; probably there was still ice along the shore of the river. Later we didn’t dream of swimming in it until June.

The valley was certainly sage-covered, however, and Ane couldn’t help seeing it wasn’t her dear Sjaelland.

And certainly no royal friends were in sight.

I’m compelled to consider the royal friends, of whom other relatives besides Elvina and May have made a great deal. In the family’s folklore, Ane and Peder were descended in some labyrinthine way from the Danish royal family. Could Ane then not have cried bitter tears over her separation from “royal friends” when she crossed Boise Ford?

At Skaaningegaard with Peder, the record shows, Ane shared a tenant farmer’s life of fealty to a royal hunting estate named “Jaegerspris,” meaning “Hunter’s Paradise.” The estate lay in the beau tiful wooded peninsula of Hornsherred between Roskilde Fjord and Isefjord. Its small castle is still there (“reminding you,” wrote an English visitor in 1859, “of an Elizabethan manor house”). The castle owned the big forest of the peninsula (“Nordskoven”) and dozens of farms in and around it, including Skaaningegaard where Peder’s family had been tenants for four generations. Like his great-grandfather, grand father, and father before him, Peder performed tasks for the castle to pay a rent and gave the castle a portion of his harvests as well. One of Peder’s special duties to the castle was to fish and hunt with the king—Frederick VII, the constitution-giver.

Ane meanwhile may possibly have been an occasional companion to Frederick VIFs low-born third wife, the Copenhagen ballerina Louise Rasmussen, whom the king designated Countess Danner. This is less certain. Was she a maid or a friend? Elvina makes Ane and the count ess friendly neighbors. At least Ane knew Countess Danner. The king and countess were Peder and Ane’s “royal friends” (though technically Countess Danner wasn’t royal enough to succeed Frederick).

Jaegerspris Castle, Skaaningegaard farmstead, and the woods of Nordskoven are still in place (as all Ane’s old scenes seem to be). One may easily fancy Peder and Ane coursing the paths between farm and castle. No book of either the castle or the farm was kept, so we’re fancy-free.

Spiky stag horns are mounted on felt panels in window alcoves of the castle, with dates of the kills below them. The dates cover Peder’s Jaegerspris service, so the panels may be said to record Peder and King Frederick’s friendship. They hunted together in the grand years after Frederick approved the constitution of 1849. As hunters will, I presume they drank many a toast before and after the hunts. It is said that above all Frederick loved drinking and hunting. Surely the bibulous king drank with companions such as Peder.

But in that event, their many skoals undid Peder, who died an alcoholic in mid-life. Drink helped derail Frederick, too, just as the crucial war for Schleswig-Holstein was beginning in 1863; the Danes lost.

In the end the countess owned the castle and its woodlands. Before his death, Frederick gave her Jaegerspris as an outright gift (since she wasn’t qualified to inherit royal property), and she wound up turning the estate to the benefit of underprivileged children. She had been less than privileged herself—a chambermaid’s illegitimate child who danced her way to success and into the king’s house. She made commoners (like Ane) her lifelong daily concern.

So while the king and Peder hunted, and then after both of them were gone, Elvina records, “Ane and her friend Louise became sincere friends and their visits were frequent exchange visits without formality.” One may hope so, for certainly Ane had need of a good, forgiving friend when Peder—forfalden til drik—hanged himself at Skaaningegaard just before Mikkelsday (the payoff day for farm hands) in the fall of 1858.[2] For seven years Ane bore the social ostracism this deed brought upon the family. She successfully ran the farm before converting to Mormonism and setting out for America.

Ane would have remembered Skaaningegaard (which she and Peder came to own outright before he died) when she crossed the Boise Ford and would have remembered, too, the turreted little red-brick castle of Jaegerspris where sympathetic Louise Rasmussen lived—Ane’s refuge, I believe, in a Lutheran world gone grim and cold for her family after 1858. Peder was barred from their parish churchyard and from heaven. None could be his advocates. Did Countess Danner and King Frederick, I wonder, provide a burial place for Peder in the woods of Jaegerspris where he had hunted?

When she crossed Boise Ford and began her American life, Ane wept, I’m sure, for those high beech woods near Skaaningegaard, and the fine castle she had known, and her gracious friend Louise Ras mussen, the countess. “Grevende Danner and members of the Roy alty . . . pleaded with them to stay in Denmark giving assurance they would not want for the necessities of life, but to no avail,” writes Elvina.

Security without redemption would have been hell, Ane saw. Perhaps by herself she could have survived—even could have served Louise Rasmussen in her project of converting the royal hunting estate to social welfare purposes (a. la modern Denmark). But Ane’s children, however comfortable in Sjaelland, would have been dogged by Peder’s disgrace.

So in 1865 she committed them to the ordeal of settlement in the Mormon American West, an ordeal that would bring them earthly, perhaps heavenly, salvation. And now in the evening of 10 April 1866, after crossing Boise Ford, she saw that she had made it. She was on the other side of the world, sunk deep in Zion’s sagebrush.

I believe it was partly relief that made her cry. She knew how much she had sacrificed—especially her personal future as companion to the commoner countess. She wept for that. She had given up Skaaningegaard too, exhausting the profits of its sale in transporting her family and a host of other new converts to Zion (as she ruefully told my father and others). And she may well have wept for the gamble she was taking—for she had no assurance she or the children would be redeemed in Zion. In fact, Anders, Peter, and Rasmus would die young of Zion’s cold weather, barely managing to start their own families; only Hans, Christine, and James would make it to the end of the century. Ane’s foreseeing spirit may have failed her then, and she wept bitterly for losing everything and gaining nothing. She must have asked God bitterly if she had not now lost enough.

She still harbored the hope that her family would blossom here from its new roots, for in the morning she went on. And it did blossom and branch. A raft of grandchildren were born before Ane died in Bear River City in 1887, and then came the big generation of great grandchildren that I belong to, who would fish and swim in the river she forded, in the country she came to.

We are her children, and she wept for us.

[1] Nelsen at twenty came from Denmark to America with Ane and more than five hundred others and kept a terse journal beginning in Hamburg about 1 May 1865 and ending in Salt Lake City 8 November 1865. Elvina A. Jensen and other of Ane’s descendants knew him in later years, and he gladly permitted Elvina to incorporate his journal into her “Sketch of Ane Larsen Andersen.”

[2] The details of this tragic event are told by Lars Nielsen, a woodcarver of Skoven, Denmark, in his Stories of the Families of Skoven, an unpublished collection of writings done in 1928 for the Local Historisk Arkiv of Jaegerspris Kommune, p. 89. The relevant stories are “Skaaningegard 9” and “Peder Andersen, d0d ca. 1857.”

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue