Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 3

Without Purse or Scrip

[1]Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints see pro claiming the gospel to all people as an important part of the church’s responsibility. Many elements of their missionary efforts have not changed over the years. Elders and sisters still knock on doors, meet people on the streets, and hold public meetings. The way in which they are supported has changed. They no longer travel without funds, nor do they depend on the hospitality of friends and strangers for room and board. For many Mormons the dependency on others for support, “traveling without purse or scrip” as it is called, is a nineteenth-century characteristic. They imagine the first missionary, Samuel Smith, Joseph Smith Jr.’s younger brother, going from house to house discussing the Book of Mormon and asking for room and board. They may also see Brigham Young, Wilford Woodruff, and other early church leaders depending on members and those friendly to the church in England. What many Mormons do not realize is that missionaries traveled without purse or scrip as late as 1950. This essay examines the church’s practice of sending missionaries with out purse or scrip and focuses particularly on those who went without funds immediately after World War II.

Background

Following the example described in the New Testament, Joseph Smith received a revelation asking missionaries to travel without funds.[2] As a result, many early missionaries depended on their contacts for room and board.[3] With time church leaders recognized the problems of missionaries wandering without support. It was difficult to find people who would help, so elders often turned to members. Brigham Young counseled against this practice in the 1860s. He “tr[ied] to get [the brethren] to go and preach without purse or scrip . . . and not beg the poor Saints to death.”[4] But that was not a consistent policy. In 1863 Apostle George A. Smith explained, “Circumstances have changed and in view of the poverty of other peoples and the wealth of the Saints that missionaries should not need to go without purse or scrip.”[5]

Several conditions made this type of missionary work practical. Al though the United States was becoming increasingly urban by the end of the nineteenth century (at least according to the census which defines a city over 2,500 as urban), there were still many Americans who lived on isolated farms. Missionaries had limited ways to contact these people. They did not have cars; there was no public transportation. If they wanted to stay in a small town, frequently there was no place to rent or even a hotel to stay in overnight. There might not be a place to find a meal. So the only way to contact everyone was to ask residents for assistance.

Eventually this policy changed. During the twentieth century, church leaders encouraged members to stay in their communities and build up the church there. In towns and cities where there were enough members, the church established congregations where the faithful could meet. The focus in some missions changed to organizing church programs instead of just finding new converts. When missionaries were in cities, it was more difficult to find people who would provide free room and board. As a result, missionaries started receiving support from their families, relatives, and friends. They used the money to rent apartments in cities. Peri odically they would still travel into rural areas for “country tracting,” often without purse or scrip.

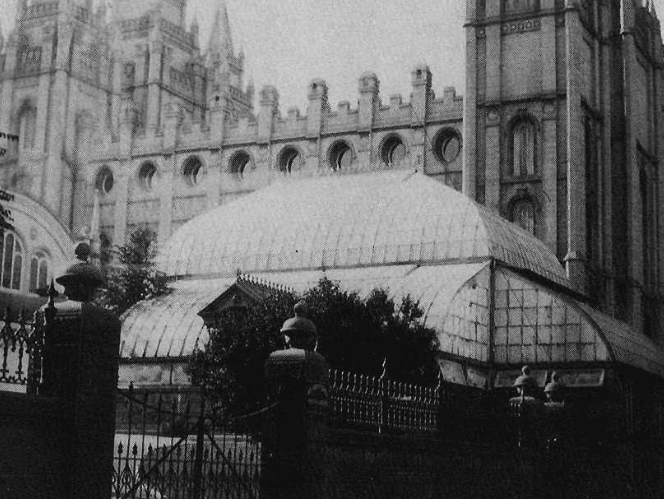

The transfer from traveling in rural areas to working in cities happened gradually. Individual mission presidents decided where missionaries worked. Some favored urban centers; others focused on agricultural areas. The California Mission is a good example. Henry S. Tanner, who became mission president in 1894, sent the first missionaries to work in Los Angeles. He had them concentrate on meeting people, inviting them to become members and attend the local branch. Tanner organized a Los Angeles branch in October 1895, and within a year the local congregation had 120 members. General church leaders expressed concerns about Tanner’s expenses as he found places for the new branches to meet, but they were impressed with the church’s growth when they visited Los Angeles. However, Tanner’s efforts did not last. He was released in 1896, and his replacement, Ephraim H. Nye, again encouraged missionaries to go with out purse and scrip and to move out of their apartments. When there was a decline in baptisms, Nye had the elders move back into the cities, and the numbers of converts increased.[6]

Reactions

How did these early elders feel about traveling without purse or scrip? The responses varied. Spencer W. Kimball, who much later became president of the LDS church, went to the Central States Mission in 1914. In November the mission president assigned Kimball and his companion, an Elder Peterson, to do country tracting for several weeks. The first day they left Jefferson City, Missouri, with overcoats and “grips” (suitcases) weighing thirty-five pounds. After walking for twelve miles, they started asking for “entertainment. At house after house we were turned away. On, on, on we dragged our tired limbs. After walking 3 mi and having asked 12 times for a bed without success we were let in a house, not wel come tho. 15 miles. Very tired, sleepy and hungry. No dinner, no supper.” For the next five weeks, Kimball recorded similar problems getting people to listen and finding a place to stay.[7]

S. Dilworth Young, who also became an LDS general authority, went to the Southern States Mission in January 1920. After arriving and buying supplies, he recalled that mission leaders “took all of our money and gave us back enough to get to our fields of labor and two dollars extra.” He and his companion started country tracting. Once two families sharing a small home invited them in. At first the families said they could feed the elders but they could not stay over night. However, after a gospel conversation, the residents decided, “We can’t let you out in a storm like that.” So the elders and the two men slept in the back room and the women and all the children bedded down in the front room. In summarizing his experiences, Young wrote, “When you go out to the country without purse or scrip, you don’t go out and beg from house to house. That isn’t the trick. You go out and preach from house to house. If you’re humble enough and tell your message well enough, they’ll invite you to stay.”[8]

Rulon Killian also served in the Southern States Mission. He arrived in October 1922 and spent the first part of his mission doing country tracting.[9] After three negative experiences on the first day, Killian and his companion sat under a walnut tree and ate nuts. Killian later wrote that when he thought of “two years of cold reception, doors slammed in his face, and other rude mistreatment, his Spirit really hit bottom. He wondered if it was worth it all.” He recalled experiences such as climbing a tree and ripping his pants, begging for leftover Thanksgiving dinner, and having his suitcases searched by a deputy sheriff for bootleg whiskey. On 28 December the mission leader told him to report to cities for the rest of the winter. Killian recorded, “Thrill! Thrill! Thrill!”[10]

Killian expressed more of his feelings about country tracting than either Kimball or Young. First, he explained, “Mormon missionaries had worked the wooded hills and mountains of Tennessee for half a century. Nine-tenths of their converts were out in the country, a little nest here, and a little nest there, twenty or thirty miles apart—not enough in any one place to form a branch.” Since many had little contact with the church after their baptisms, he felt it was a “miracle” they remained Mormons.[11]

Killian did not think country tracting was effective missionary work. He felt “the Elders do too much walking and too little good missionary work. I feel we have been ‘walking’ away from opportunities.” He told the elders in his district, “Let’s change.. . . When you find interested people, stick with them and preach until they know something about our church and doctrine. Let us MAKE baptisms instead of HUNT them.” He recalled teaching a Mrs. LeFever whom the missionaries had been visit ing for thirty years. When he asked why, she said the missionaries had not gone beyond discussing faith and repentance. Killian and his companion developed lessons based on the Articles of Faith. As a result, the woman and her two children asked to be baptized.[12]

Killian’s views were not typical though. Many mission leaders saw value in country tracting not only for the people but for the missionaries. In 1928 Elias S. Woodruff, president of the Western States Mission, explained, “It would be wise if every elder in the mission could have at least two weeks every year, traveling without purse or scrip,” because “it would bring them nearer to the Lord and nearer to the people.” Although elders found the experience “perhaps not altogether a pleasant one,” they told the president that “it was a good thing to do.” He recalled two missionaries who “started out with great confidence; when they discovered that the Lord was blessing them and raising up friends for them they were over-confident, with the result that they had to spend one night in a corn field.” Woodruff continued, though, “They were soon humbled and thereafter in response to their appeal they were never without friends.”[13]

In 1937 William T. Tew, president of the East Central States Mission, continued to send his missionaries into the country during the summer. In a letter to the missionaries’ parents, he explained that by doing the summer work, the missionaries had “done much to extend the frontier of Mormonism among non-members.” Tew continued that the work was “strenuous and self denying” but the missionaries were blessed.[14] Tew also asked the missionaries to work in the cities for eight months where there were chapels and to come back to these centers after two or three weeks to relieve the stress of country work, check on the branches, and encourage the branch members.[15] He promised them that if they would travel the roads and meet people, “they will entertain you and give you a meal and bed.” So that members were not left without the church organization, Tew told missionaries to organize home Sunday schools and to hold meetings even if only a few attended.[16]

Until World War II, missionaries in the United States continued to travel occasionally during the summer without purse or scrip. The practice varied from mission to mission; usually mission presidents decided if elders should do summer work and for how long. The focus of country tracting was to find people and to share the message of Joseph Smith and the Restoration. If those people joined, elders returned to visit the con verts, present gospel messages, baptize children who had turned eight, and encourage families to stay true to the church. Sometimes mission presidents sent missionaries to conduct a census of members who had not been contacted for several years.

Without Purse or Scrip, 1940s–50s

Little mission work took place between 1941 and 1945 because of World War II. Following the war, church leaders started sending more missionaries throughout the U.S. and reopened the European missions. In September 1947 there were forty-two missions. Since many young Mormon men had had to delay missions because of military service, 70 percent of one mission class that month were former servicemen.[17]

Surprisingly, some new mission presidents asked elders to go into the country and travel without purse or scrip. The first to do so was S. Dil worth Young, already a member of the Quorum of Seventy, who presided over the New England Mission. He recalled when he arrived at the mission home in May 1947 that the former president, William H. Reeder, con ducted a missionary conference and did not include Young. Once he was in charge, Young found the elders ‘Tow in morale with no spirit.” So he decided to send them into the country the same way he had been initiated into missionary life.[18] Russell Leonard Davis, who served under Young, recalled, “When Dilworth Young arrived as mission president, the mission just wasn’t doing well” because the “missionaries had false pride.” Davis continued, “He instructed us by telling about his first week in the mission field in the Southern States. … He said it rained all the time and they didn’t have a place to get dry. Then he said to us, ‘Now re member, no matter how bad your first week is, it can’t be as bad as mine.'”[19]

Young told the missionaries to buy grips similar to the one he had carried in the Southern States Mission. Each missionary carried enough money to meet the requirements of vagrancy laws, two dollars in Massachusetts, five in Maine, and ten in Canada. Young also gave them instructions to contact the police and tell them what they were doing. Elders were to say that they were “dependent for their physical needs upon the hospitality of those who want to hear our message” rather than say they were traveling without purse or scrip. The missionaries gave the mission home the address of where they would be each Saturday, and mission leaders would forward mail, literature, and money for clothes and hair cuts there. Young explained, “It shouldn’t cost more than $20 per month to live on this basis.”[20]

With these instructions, the elders departed for the country. Truman Madsen recalled, “In the early stages we were so preoccupied with our stomachs and with the question of lodging that we, in fact, failed. . . . When we … decided we would put bearing witness and arranging meetings first and not worry about our stomachs, the work began to succeed.”[21] That first summer elders sent back reports of their successes and difficulties. The mission office compiled these comments and mailed them out to the elders. Lloyd W. Brown and C. P. Hill found that people would not listen until they helped with a haying crew. The next day “we found that nearly every door was open to us and inviting us to eat and sleep and discuss the Gospel.” Elders continued in the country into October. They spent ten weeks without funds, and during that time they aver aged sleeping outside two nights. One set of elders in New Brunswick reported sleeping outside twenty-one nights; another set in Nova Scotia had a place to sleep every night and never had to ask for a meal.[22]

One missionary, Hale Gardner, said Young’s announcement troubled some local members who considered the president’s plans “laughable” and “doomed to failure” because “the New England people, it was said, were too cold and inhospitable.” Parents were also concerned and wrote to the general authorities. In response, Young wrote to his fellow church leaders in October 1947, explaining that “there is only one way to do missionary work.” First on his list was “go without money where possible,” last was “learn to depend on the Lord completely.” George F. Richards, president of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, responded to Young’s re port that he had given “careful thought… and courageous effort and the results seem to be very satisfactory.”[23]

Truman Madsen recalled that when Elder Harold B. Lee came to visit the mission, some missionaries believed it was to ask Young to stop sending elders to the country without money. However, after Lee finished visiting the mission, he found that the elders were “rather bedraggled but all [were] full of dedication.” Madsen concluded, “[Lee] returned to Salt Lake and encouraged the brethren to support the plan.” After giving his report, Lee wrote back to Young, saying that the general authorities “were all very much interested in what I had to say because of the comments for and against, no doubt, that had been made.” He continued that if he had a son going on a mission he would want him to work with Young in the New England Mission.[24]

One missionary serving in the New England Mission was Oscar McConkie, Jr. His father was the mission president in California, and McConkie Jr. wrote about his country experiences to his father. La Rue Sneff, who served as a secretary to Oscar McConkie, recalled that the mission president read his son’s letters to the missionaries in the office. According to her, “The elders were sitting around the table saying, If we could only do that’ [go without purse or scrip].” She explained that vagrancy laWain California prevented McConkie from considering it.[25]

Eventually, as in New England, McConkie worked around vagrancy laws by asking the missionaries to carry some cash. According to his son, he prayed and asked to have the faith of Enoch. Soon “he realized that he could have prayed until his tongue went dry, but … he had to have the works of Enoch and Elijah to develop that faith.”[26] Spencer J. Palmer de scribed McConkie as “a man of unflinching faith” who felt he was “entitled to constant revelation in the administration of the California Mission.” The president’s request surprised Palmer, but he continued that McConkie “believed that we had a shortage of faith among the missionaries. We were not baptizing as we should because we were not humble or loving enough.”[27] Douglas F. Sonntag said he used to “kid the president.” After getting a “letter from Oscar in New England that told how great this going without purse or scrip was,” Sonntag said McConkie felt, “I’ll get these missionaries out of their beds one way or another.”[28] This became the mission story. Carl W. Bingham who arrived in the mission in December 1948 said, “I was told that the reason for us traveling without purse or scrip was because the missionaries were too comfortable in their apartments and were not doing much missionary work.”[29]

In August and September 1948 the mission president visited all the elders and asked them to go without purse or scrip. The mission’s quarterly report explained that they voted unanimously in favor of the plan.[30] James B. Allen, who had just arrived in the mission two months before McConkie’s request, wrote his reaction in a journal. “Boy, what a surprise.” While Allen felt, “It’s rather strange to think that right now I have no idea whatever as to where I’ll be sleeping tomorrow night,” he concluded, “this experience is going to humble us and teach us to put our faith and trust in the Lord.”[31] Grant Carlisle, who had been on his mission for sixteen months, was Allen’s companion. He also recalled his first reaction, “It was kind of scary because I didn’t know what it would be like.” He recalled their landlady was interested in the church. She gave them a refund on their rent, but, Carlisle added, “She felt bad that we had to give up everything and just head out with no place to stay and no place to eat unless we begged off the people. It was quite disappointing to her.”[32]

As in the New England Mission, some members did not approve of McConkie’s plan. Carl Bingham said, “The instructions for missionaries to travel without purse or scrip were accepted by different people in different ways. Usually the members who were humble, sincere and anxious for the work to proceed accepted it without reservations. Some of the more affluent and wealthy members felt it was degrading to the missionaries as well as to the elders.”[33] Spencer Palmer said some local leaders in Los Angeles wrote to church president George Albert Smith protesting McConkie’s decision. But Smith wrote back supporting McConkie’s decision since he had “the keys of administration and revelation for all affairs affecting his mission.”[34] This was probably not the majority though; James Allen said he only got positive feedback from members. They supported the missionaries because they were doing what the mission president wanted.[35]

Most missionaries accepted McConkie’s challenge and learned to adjust. Carl Bingham said, “I soon fell into the routine of the work and learned to accept the method as the will of the Lord and the way we were intended to work.” Bingham worked as supervising elder and felt, “The missionaries I was called to preside over accepted the program and to the best of my knowledge did what was necessary to make it.”[36]

Ogden Kraut remembered that traveling without purse or scrip was difficult because “there was no cookbook to go by on how to do it. We just went out there and struggled along trying to figure out how to do it the most effective way.” He continued that by the end of his mission “I felt that I could travel around the world that way. … It was easy for me to do.” He said people asked him if he missed meals, and his common response was “no but I’ve postponed a lot of them.” Kraut felt some missionaries were not as faithful. He claimed, “Some . .. packed up their bags when they got the announcement.” Others, he said, took apartments without the mission president’s knowledge or stayed with members.[37]

Other mission presidents also asked their elders to travel in the country. However, California was the only mission that did it full time. Francis W. Brown, for example, was president of the Central States Mission. That mission’s historical report for 31 March 1948 explained, “It is also the de sire of the Mission President to send each Elder into the country without purse or scrip to take the gospel to the many people in the Mission who have not had the opportunity of hearing the gospel for many years. We feel that much good will be accomplished through this, both for the people contacted and for the Elders.”[38] Hyrum B. Ipson, who was in the Central States Mission, explained that Brown did not suggest that missionaries go without purse or scrip until after “Dil Young” had tried it in the New England Mission.[39]

When the elders returned from the first summer, the quarterly report noted, “Many have said that they feel it is one of the[ir] greatest blessings.” One missionary explained why: “We were never tested above our capacity to endure, and I can think of nothing that would build a per son’s faith in a Living God than to be taken care of from day to day among the people who know nothing about us individually.”[40] As a result, the next summer the elders returned to the country.[41]

Other mission presidents who sent elders out without purse or scrip included Thomas W. Richards in the East Central States Mission, Albert Choules, Sr., in the Southern States Mission, Edward Clissold in the Central Pacific Mission, Creed Haymond in the Northern States Mission, and Loren F. Jones in the Spanish American Mission.

Reasons

Mission presidents and elders and LDS publications suggested why missionaries went without purse or scrip during the late 1940s and early 1950s. Interestingly enough, although others might have had the same feelings, only one interviewee, Ogden Kraut, mentioned that it was a commandment. Kraut arrived in the California Mission in September 1948 just after McConkie had asked elders to go without purse or scrip. Kraut had been praying for the opportunity to travel as Christ’s apostles had and planned to ask McConkie if he could work that way during his first interview. But Kraut never had to ask the question; an elder who had a layover in Los Angeles before going on to Hawaii came out of McConkie’s office just before Kraut went in. The elder reportedly ex claimed he was glad he was not staying in California since the mission president had just informed him that elders were traveling without purse or scrip in that mission. Kraut saw McConkie’s decision as an answer to prayer. Shortly after Kraut finished his mission, McConkie also left the mission, and the new mission president adopted a new approach.

Kraut felt the scriptural reasons for traveling without purse or scrip were very important. He believed that anyone going on a mission should travel that way because “it’s a commandment.” He felt that the missionary program began to deteriorate when elders “began to rely on the money from home instead of in the Lord. That’s not the way it’s supposed to be done. They changed the rules on the Lord. He didn’t.”[42]

Some elders said they referred to the scriptures occasionally when they asked people for a place to stay. They would say they were traveling as Christ’s disciples had and were depending on people for food and lodging. Boyd Burbidge, who served in the Spanish American Mission from 1949 to 1952, said he would “read out of the Bible where Peter, James, and John and the apostles went among the people without purse or scrip and the people would take care of them and help them.”[43] However, these interviewees did not express the view that this was the only way to do missionary work.

So what were the reasons for traveling without purse or scrip? The reason suggested most often was the benefits to the missionaries. According to Don Lind, who was in the New England Mission from 1950 to 1952, the summer he spent country tracting resulted in few baptisms but “for the missionaries it was a time of great spiritual growth.”[44] Owen Leon Wait, who served in the Northern States Mission from 1947 to 1949, said his mission president Creed Haymond “wanted the Elders to learn humility and faith thru these experiences.”[45] Haymond told the Church News, “If this work did nothing else it made good missionaries.”[46] Missionaries frequently referred to their experiences as “humbling” and added statements such as the experience had helped them in “de pending upon Heavenly Father and putting my total trust in Him.”[47] According to Russell Davis, missionaries “were blessed. Most important of all we became humble and changed our attitude.” Davis continued that his experience “kept the gospel strong in my life and strong in the family. It changes you so that you do the Lord’s work for His reasons and for the people that you serve and not for your own.”[48]

Hiton Starley who served in the Central States Mission remembered that as missionaries returned to Independence, Missouri, after country tracting they were “stiff, sore and dirty but thankful that we had the Spirit of the Lord in greater abundance than we had had it before because we had to call upon the Lord and depend on him for our food and shelter all the time.” That experience convinced Starley that the Mormon church was right. During the summer he had only had to sleep out twice and had never missed more than two meals in a row. “I truly believe the scriptures when they tell us that the laborer is worthy of his hire, because the Lord repaid me many times and in many ways for the little bit of work that I have done for him.”[49]

Did traveling without purse or scrip increase baptisms? Irven L. Henrie, in the New England Mission from 1948 to 1950, believed that “direct baptisms from country tracting were few but spirituality increased such that the overall mission baptisms increased.”[50] Several missionaries in the California Mission felt they had more baptisms. Spencer Palmer and his companion were working in a small town in Lone Pine, California, when McConkie asked them to go without purse or scrip. His companion Evan Stephenson was not “thrilled with the idea” of leaving their apartment, “expecting the hard nosed people of Lone Pine” to take care of them. But they had considerable success. Before they had had no baptisms, but after a year of asking for support they had enough members to establish a branch. Palmer continued, “It was not because we had changed in terms of our talent, but because we had humbled ourselves and had finally lived up to the spirit of our calling. The blessings of the Lord rested upon the minds and the hearts of those people.”[51]

Mission president McConkie was also encouraged because missionaries could “reach male members of the families and bring converts rather than the predominantly female converts as has frequently been the case.”[52] E. Franklin Heiser spent his first three weeks in New England traveling without purse or scrip before he went into the cities for the win ter. He remembered, “President Young told us that the bigger cities had been tracted and tracted and tracted. He knew there were thousands out in the country who were not receiving the gospel. . .. The most practical way was doing without purse or scrip.” The mission only had two cars; the elders could not use bicycles. They could use public transportation, but it didn’t go into the rural areas.[53]

Grant Carlisle felt that just by staying with people missionaries had a good influence even if they did not baptize. “I don’t remember that we really did much gospel talking to them or not while we stayed the night. Maybe we socialized too much. We talked about Salt Lake. I guess that was good to talk about the temple and the Church.” But he had also questioned his effectiveness in his mission work before going without purse or scrip. At least when they stayed with people he felt, “We were meeting with the people. It was our influence of being with them rather than preaching to them. We gave a good example of missionaries.”[54]

Some missionaries did not question why they were asked to go with out funds; they felt it was their responsibility to follow their leaders. Carl Cox, who served in the Northern States Mission from 1947 to 1949, said, “My mission president was a good man, and I looked up to him. … I did what needed to be done.”[55] Don Lind said when he came to the New En gland Mission missionaries were already going without purse or scrip. He was not sure how he would have reacted if he been in the mission be fore, but since the policy was established, he felt it was the norm.[56]

Several missionaries thought that traveling without purse or scrip worked because of the period. Jesse N. Davis explained, “We were just in a transition period at that time. People before World War II kind of trusted each other. After the war there were so many things that went on with robberies and other bad things happening to people that they were afraid to take you in.” Hitchhiking was a not problem; people would pick up the elders. But Davis explained, “I don’t know whether you could do it in this day and age or not.” He was sure that the hitchhiking would not work. Even after the war people in southern Ohio were “apprehensive of strangers.”[57]

Problems

Several missionaries, however, questioned the effectiveness of going without purse or scrip. Owen Leon Wait took his inability to find people to baptize personally. He wrote, “My lack of success pained me then and has grieved me ever since…. I had no complaints at the time. I accepted whatever came as the will of God.”[58]

Why was Wait not able to find people to baptize? Some missionaries said they spent too much time asking for food and places to stay. That left little time to teach. Norman D. Smith in the California Mission said during the day missionaries did not get food because they were at homes between meal time. At night, though, the people who entertained them “were expected to feed us and provide a place to stay if they accepted us. It seemed like we were so busy involved with eating and then getting ready for bed that we just had to teach or try to get them to ask us questions about the gospel between mouthfuls. It’s kind of like Elder Peterson would talk and I’d eat. Then I’d talk and he’d eat. We’d kick each other and trade off sort of. I don’t think we really kicked each other, but it was kind of between bites.”[59]

Douglas Sonntag agreed: “In my opinion there would have been a much more efficient way to do missionary work. . . . Some of the towns stopped the missionaries and charged them with vagrancy. … It seemed to me they spent most of their time trying to find a place to stay.”[60]

Jesse Davis said it was always hard to talk to people with no appointment and no advance contact. “Just going in cold to visit people outside the cities made them suspect then, and I think they’d be even more so now.” While he had some experiences where people seemed to be waiting for missionaries, he said that usually “Even if it’s a neighbor introducing you, it’s just a foot in the door.”[61]

Orvil Ray Warner explained that his mission president, Thomas W. Richards, in the East Central States Mission had them go without purse or scrip because Richards felt “that everybody had to hear the gospel no matter where they lived.” Yet Warner explained, “It was not an effective way to do it looking back on it.” He continued that he baptized twenty five people, mostly in the country. “They had no place to go to church… . They had no other members with which to associate. . . . There was no place to participate in church programs. Consequently, after awhile they would drift away and leave the Church and go with the neighboring community church.” Warner continued that while traveling without purse or scrip built missionaries’ testimonies, “leaving people alone in the mission field like that is probably not a wise idea.”[62]

Ending the Practice

Like missionaries, mission presidents serve for a limited period. S. Dilworth Young was replaced by Howard Maughan in the New England Mission in 1951, and David Stoddard took over Oscar McConkie’s California assignment in 1950. The other mission presidents also finished their service between 1950 and 1952. The new presidents did not continue having missionaries travel without purse or scrip. The missionaries and LDS church publications suggest several reasons.

Oscar McConkie, Jr., said one reason was the different nature of the mission presidents. Young asked the missionaries to go without purse or scrip because he had that experience as a young man. McConkie continued, “The man who replaced him no doubt was just as good a man as President Young, but he hadn’t had that experience and didn’t have that sort of drive to do it.” He also said that missionaries did not continue to go without funds “because I think people don’t have enough guts.”[63]

One reason was the increased use of the automobile. Although cars had been popular since the 1920s, the U.S. government had rationed them during World War II. There was still a shortage just after the conflict ended. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, missionaries started purchasing cars to use in their missionary work. First Presidency circular letters in 1956 and 1958 discouraged purchasing cars unless they were necessary. But they did not outlaw the use of personal cars. As a result, some missionaries purchased their own vehicles. In 1963 the church started purchasing automobiles for the missionaries to use.[64] Cars made it possible for elders to establish headquarters and then travel throughout the area. Also, since they did not have to walk, ask for rides, or depend on public transportation and could travel faster, they could see more people. According to an article in the Church News in 1949, missionaries in North Carolina and Virginia who had cars were “able to conduct more cottage meetings than would otherwise be possible.”[65]

During the late 1940s and early 1950s missionaries also started using standardized discussions to teach investigators. Before then, some missions had used LeGrand Richards’s “Messages of Mormonism” which he developed after his work as president of the Southern States Mission in 1937. His outline eventually became the book A Marvelous Work and a Wonder. Other missionaries and mission presidents wrote lesson presentations following gospel themes and using “well-known salesmanship techniques.” Richard L. Anderson, a missionary in the Northwestern States Mission, wrote such a plan that his mission used in 1948. As a result, baptisms increased from 158 during the first six months of that year to 358 during the second six months. Other missions adopted the Ander son Plan, modified it, or developed their own plans.[66]

Mission leaders adopted these plans at the time that missionaries were going without purse or scrip. Because of that change, Don Lind, who worked under Young and Maughan in the New England Mission, said: “It’s hard to compare the country tracting versus no country tracting because we were making a major change and improvements that were going to increase the relative number of converts.”[67] The major change he referred to was using missionary discussions.

Mission presidents had varying reactions to the Anderson Plan. Some embraced it, others felt that it was unnecessary. James Allen re called that Oscar McConkie did not like the plan; he felt that it took away from teaching by the spirit.[68] S. Dilworth Young, however, was constantly looking for new ways to do missionary work. He told the missionaries, “Try it. If it works, fine. We need something to wake these people up.”[69]

Conclusion

When Oscar McConkie returned from California, he reported he had established the practice of traveling without purse or scrip “on a permanent basis.”[70] Other mission presidents were not as convinced that there was only one way to do missionary work. After serving as a mission president, S. Dilworth Young told a grandson that going without purse or scrip was not necessary. “It is a case of which prophet is speaking. Joseph Smith was instructed to use the system. The present leadership instructs elders to receive their support from home.” He explained that Jesus Christ had sent missionaries with and without funds. When Young was mission president, he even defended missionaries working in the cities, explaining, “If travel without P & S is the only way to get humility, the Church would have been dissolved long ago.”[71]

An important question only occasionally mentioned directly by missionaries was the underlying reason for doing missionary work. Is the purpose to convert non-Mormons or missionaries? Are missions only to warn people? If people accept the gospel, should they have a place to worship? The experiences of missionaries traveling without purse or scrip show that the message has not always been clear. Many traveled without money and their mission leaders said the experience was important to convert them. Yet what did it do for non-Mormons? Sometimes they did not hear enough of the gospel to be interested in what the missionaries were saying; other times it took years for them to convert because they did not see the missionaries often. And if they lived in outlying areas, it was often difficult for them to attend church meetings. Yet if missionaries only stayed in cities, they missed teaching people who might be interested.

Automobiles and highways have helped resolve most of these problems. People in rural areas can get to cities or towns to attend church meetings; missionaries can get to rural people to share the gospel. A new problem is inner city Saints getting to the suburbs to attend meetings. As a result, the church is establishing small, inner city branches so that members can worship close to home. A focus on providing a place for con verts to worship, new teaching methods, and improved transportation along with a changing society that might not be as willing to entertain strangers might be some of the reasons why missionaries no longer travel without purse or scrip.

[1] Most of the sources used for this essay explained that only elders were asked to travel without purse or scrip. The only possible reference to sister missionaries doing country work was in the East Central States Mission Historical Record. The report said the lady missionaries had been moved from Knoxville to Slate Springs and “thoroughly enjoyed their labors in the country.” It is not clear if they were doing country tracting or if they had just moved to a more rural area. East Central States Mission Historical Record, 30 Sept. 1948, 5:13, archives, Historical Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah (here after LDS archives).

[2] Traveling without purse or scrip is described in Luke 10:1-5; Smith’s revelation is in Doctrine and Covenants 84:77-90.

[3] For additional information on Mormon missionary efforts, see the index listings in James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1992).

[4] John A. Widtsoe, ed., Discourses of Brigham Young (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1978), 322-23.

[5] George A. Smith, 6 Apr. 1863, Journal of Discourses (Liverpool and London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854-86), 10:142.

[6] Chad M. Orton, More Faith than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 18-19,22, 25,26.

[7] “The Mission Experience of Spencer W. Kimball,” Brigham Young University Studies 25 (Fall 1985): 115-17.

[8] Benson Y. Parkinson, S. Dilworth Young: General Authority, Scouter, Poet (Salt Lake City: Covenant Communications, 1994), 59, 64-65, 70.

[9] In the South elders worked in the country during the winter and in the cities in the summer to avoid malaria (ibid., 65).

[10] Autobiography, in Rulon Killian Papers, 1:17, 24,26, 27,43, LDS archives.

[11] Ibid., 3:5.

[12] Ibid., 9:1,5.

[13] Elias S. Woodruff, Conference Reports, Oct. 1928 (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1928), 55.

[14] William T. Tew to Parents, 20 Oct. 1937, East Central States Mission President Files, 1937-40, LDS archives.

[15] William A. Tew, Suggestions to Missionaries in East Central States Mission, Aug. 1937, East Central States Mission President Files, LDS archives.

[16] William T. Tew, 14 May, 12 July 1939, East Central States Mission President Files, LDS archives.

[17] “From Whence Come Missionaries/’ Church News, 27 Sept. 1947,6-7.

[18] Parkinson, 226.

[19] Russell Leonard Davis Oral History, 6, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 20 Feb. 1995, LDS Missionary Oral History Project, Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, Manuscript Division, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University Provo, Utah (hereafter referred to as LDS Missionary).

[20] Parkinson, 226-27.

[21] Ibid., 228.

[22] Ibid., 229-30.

[23] Ibid., 237-39.

[24] Ibid., 237-38.

[25] La Rue Sneff Oral History, 5, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 14 Oct. 1994, LDS Missionary.

[26] Oscar McConkie, Jr., Oral History, 2, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 20 Sept. 1994, LDS Missionary.

[27] Spencer John Palmer Oral History, 6, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 22 Mar. 1994, LDS Missionary.

[28] Douglas F. Sonntag Oral History, 10, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 11 Apr. 1994, LDS Missionary.

[29] Carl W. Bingham Letter, on file in Redd Center for Western Studies.

[30] Entry dated 11 Sept. 1948, Manuscript Report, California Mission, Report ending 30 Sept. 1948, LDS archives.

[31] James B. Allen Oral History, 6, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 1 Mar. 1994, LDS Missionary.

[32] Grant Carlisle Oral History, 5, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 23 Mar. 1994, LDS Missionary.

[33] Bingham Letter.

[34] Palmer Oral History, 6.

[35] Allen Oral History, 20.

[36] Bingham Letter.

[37] Ogden Kraut Oral History, 4-5, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 16 Feb. 1994, LDS Missionary.

[38] Central Sates Mission Historical Record, 31 Mar. 1948, 6, LDS archives.

[39] Hyrum B. Ipson Conversation, notes in my possession.

[40] Central States Mission Historical Record, 30 June 1948,18; 30 Sept. 1948, 32.

[41] Ibid., 30 June 1949, 20.

[42] Kraut Oral History, 11.

[43] Boyd M. Burbidge Oral History, 10, interviewed by Marcie Goodman, 3 Nov. 1992, LDS Missionary.

[44] Don Lind Survey Form, Redd Center for Western Studies.

[45] Owen Leon Wait Survey Form, Redd Center for Western Studies.

[46] “Pres Haymond reports work in Northern States,” Church News, 2 Apr. 1950,4.

[47] Alden M. Higgs Survey Form, Redd Center for Western Studies.

[48] Davis Oral History, 14.

[49] Elder Hiton Starley, “My Experience in the Country,” Church News, 29 Dec. 1948,14.

[50] Irven L. Henrie Survey Form, Redd Center for Western Studies.

[51] Palmer Oral History, 11.

[52] Mission President Progress Report, Church News, 10 Apr. 1949,15.

[53] E. Franklin Heiser Oral History, 7, interviewed by Marcie Goodman, 22 Nov. 1992, LDS Missionary.

[54] Carlisle Oral History, 15.

[55] Carl Cox Survey Form, Redd Center for Western Studies.

[56] Don Leslie Lind Oral History, 19, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 19 Feb. 1995, LDS Missionary.

[57] Jesse N. Davis Oral History, 13, interviewed by Rebecca Vorimo, 15 June 1993, LDS Missionary.

[58] Wait Survey.

[59] Norman D. Smith Oral History, 5, interviewed by Rebecca Vorimo, 1 June 1993, LDS Missionary.

[60] Sonntag Oral History, 6.

[61] Davis Oral History, 13.

[62] Orvil Ray Warner Oral History, 14-15, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 27 Jan. 1995, LDS Missionary.

[63] McConkie Oral History, 7-8.

[64] First Presidency circular letters, 5 Dec. 1956, 27 Jan. 1958, and 2 Aug. 1963, LDS archives.

[65] “Missionaries contact saints isolated from church center,” Church News, 16 Mar. 1949,16.

[66] Allen and Leonard, 548-49.

[67] Lind Oral History, 16.

[68] Allen Oral History, 7.

[69] William Berry Oral History, 7, interviewed by Lynn DeWitt, 31 Jan. 1995, LDS Missionary.

[70] “Pres. McConkie Tells Joy of Mission Growth,” Church News, 6 Sept. 1950,1.

[71] Parkinson, 239. In Luke 10:4 Christ told the seventy to “carry neither purse nor scrip.” In Luke 22:35-36 he told the apostles, “But now, he that hath a purse, let him take it.”

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue