Community of Christ

Introduction

Within these articles, Dialogue delves into the history, beliefs, and practices of the Community of Christ. The Community of Christ, formerly known as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS Church), traces its origins to Joseph Smith III, the son of Joseph Smith Jr., who founded the LDS Church. It explores the evolution of the RLDS Church into the Community of Christ, as well as its distinctive theological perspectives and organizational structure. Find a wealth of articles from a variety of perspectives, contributing to a well-rounded view of the Community of Christ and its place within the broader landscape of Mormonism.

Mormon Women in the Ministry

Emily Clyde Curtis

Dialogue 53.1 (Spring 2020): 129–142

Interview with Brittany Mangelson who is a full-time minister for Community of Christ. She has a master of arts in religion from Graceland University and works as a social media seeker ministry specialist.

In our Church, we often see continual revelation and innovation. For years, we have watched men expand their roles in leadership callings. It comes as no surprise that there are LDS women who feel called by God to practice pastoral care in ways that go beyond what is currently defined and expected for women in our religion. Here we define pastoral care as a model of emotional and spiritual support; it is found in all cultures and traditions. In formal ways, we see women provide this type of care when they teach and lead in the auxiliaries, serve as ministering sisters, and serve missions. We also see this when a sister holds the hand of another during a difficult sacrament meeting or brings a casserole to a home where tragedy has struck. Women are well-trained to provide service as one of the ways to minister to their ward and stake community.

As these women show, ministry can be so much more. The path of ministry sometimes means going to divinity school, working as a lay minister, or even seeking ordination in a Christian tradition outside of the LDS Church where women can be ordained. We have asked the following women to share their stories about how they have expanded their ability to minister through theological education and their chosen pastoral vocations. As pioneers who are expanding the roles of ministry for Mormon women today, we also ask how the Church can enhance the traditional model of women’s ways of ministering and how this can be shaped by future generations.

Katie Langston converted to orthodox Christianity after struggling with Mormonism’s emphasis on worthiness. She is now a candidate for ordination in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and works at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Brittany Mangelson is a full-time minister for Community of Christ. She has a master of arts in religion from Graceland University and works as a social media seeker ministry specialist.

Rachel Mumford is the middle school chaplain at the National Cathedral School, an Episcopal school for girls in Washington, DC. She is an active participant in both Episcopal and LDS communities of faith, reflecting her Mormon heritage as well as the resonance she finds in Episcopal tradition.

Jennifer Roach is a formerly ordained pastor in the Anglican tradition. She is a recent convert to the LDS Church and had to walk away from her ordination in order to be baptized. She works as a therapist in Seattle.

Nancy Ross is a professor and ordained elder and pastor for the Southern Utah Community of Christ congregation.

Fatimah Salleh began life as Muslim, converted to the LDS Church as a teenager, and was recently ordained a Baptist minister after attending Duke Divinity School. Her call to ministry is part of a colorful journey into finding a God for all and for the least.

How do you think members of the Church traditionally define the role of women as ministers?

Brittany: “Ministry” or “ministers” are not words I heard much growing up LDS. Traditionally in the Church, the work of women is largely confined to what they can do to serve the youth, children, and other women. Women do not lead men and are expected to serve as a helpmeet to offer support. Women in the LDS church take great pride in being part of the Relief Society and do a fabulous job of networking with other women in compassionate services and ministries to their local congregations. As we have seen, however, women’s voices and spiritual gifts have virtually no place in major decision-making conversations. Most members do not seem overly bothered by this.

Rachel: I see this Church definition to be grounded in the idea of service to God through service to others. This draws from the meaning of “minister” as an agent acting on behalf of a superior entity. Until recent direction from Church leadership, members didn’t refer to the idea of “ministry” often, at least in my generation. What I have heard in the last year has been focused on developing a personalized relationship with other members of the ward, particularly those assigned through the ministering program, through attention to their various needs. It’s essentially visiting and home teaching, but with a more flexible, open-ended approach to connecting with others.

Katie: I’m not sure that “ministry” in general is a term that Mormons use very much; even the new home and visiting teaching programs are referred to as “ministering,” which connotes a particular action people take, as opposed to a “minister,” which confers a kind of identity. Having said that, my experience growing up in the 1980s and ‘90s was that women’s contributions to the community were expressed in terms of nurture and charitable service, with motherhood being extolled as the highest expression of this role.

How do you see your role as a minister? How is it different and how is it similar to the traditional Church model?

Nancy: A few months ago, I became the pastor of my congregation. I have had a lot of mentorship leading up to this and support now that it is my role. Being a pastor is very different from being a bishop, whose job it is to give counsel. My job as a pastor is mostly to listen and affirm that people are loved by God—that they are whole and worthy regardless of whatever brokenness they feel. I organize meetings and events, but I do so with the help of everyone in my congregation.

Fatimah: I view my role as a minister as being more expansive and deeper than the role in the LDS tradition. I am ordained to be present in hard circumstances, and I have to learn the skill set of presence work: how to show up at hospitals, prisons, at places of pain, and be emotionally and spiritually prepared to help others carry their pain.

In the hospital where a mother was saying goodbye to her son, who was killed in a drunk driving accident, I was called to the bedside, and I was called to walk with this mother in deep rage and grief. I wasn’t there to defend God but to hold grief and deep sadness with a mother. My job is not to fix or defend God and not to try to make hard situations okay.

Rachel: I carry the person-to-person ministering role in my LDS Church community, seeking to care for others in a way that feels genuine on both sides, to know one another and care for each other on the long journey of life. In addition, I also have a specific role in the spiritual leadership of my Episcopal school community. This is being a “minister” in the other sense, as a member of the clergy with a calling and responsibility to serve in an official capacity in the community. While I do not officiate in some aspects of the Episcopal liturgy that necessitate an ordained priest, I do work hand in hand—and heart in heart—with my fellow chaplains to plan and lead our services and offer pastoral care to our community.

Brittany: Along with three other women, I lead the entire congregation in worship, fellowship activities, community outreach, and education and development of our congregants. My ordination and status as a minister are pivotal to this work. I see my role as a pastoral presence in moments of crisis and in the midst of debilitating faith transitions. My job as a minister is a promise I have made to my church, to God, and to the people I serve that I am committed to peacemaking and reconciliation. I will be there to listen, to walk with, and to hold out an invitation to know a God who loves unconditionally.

Katie: I’m very Lutheran in the sense that I believe strongly in the priesthood of all believers and that all baptized Christians are called to ministry. My particular call as a public leader in the church makes me no more or less a minister than the nurse, teacher, entrepreneur, service worker, or garbage collector in the pews. The call of public leadership is to preach the gospel of grace, to administer the sacraments of baptism and communion to the people, to speak to contemporary matters of justice and morality, and to be present at the threshold moments of people’s lives: birth, death, and transitions of all kinds.

What are your spiritual gifts?

Brittany: I think my spiritual gifts are the ability to be fully present in the moment, to have true empathy, and to find a point of connection with almost anyone I meet. I am able to make people comfortable almost immediately, and that is simply an aspect of my personality. In many ways, I feel that our spiritual gifts are simply an extension of who we are. I use them constantly, not simply at church or when I’m engaged in church work. Developing them has benefited me in just about every aspect of my life.

Fatimah: One of my spiritual gifts is a love of the scriptures. I work with both other pastors and congregants to understand the scriptures in a way that shows them God and helps them hear God’s voice. In these works, I can see how social justice is carved out in the word of God.

Rachel: I have a seeking, hopeful heart. I find joy in asking questions about the nature of life, humanity, and divinity, and I marvel at the many ways that people have explored these questions over time and place. I can find existential wonder in the contour of a line, the dialogue of an ancient story, or the burst of sound. I can listen and I can love. I feel with others the range of joy through sorrow. I love the craft of words, I find spiritual expression in writing, and I revel in the spiritual tension and expanse of scripture, poetry, and story.

I feel most alive spiritually when I am teaching, writing, planning worship with others, or in one-on-one conversation. My work as a school chaplain feels truly like a vocation, being called through experience to the work where I can give with a whole heart. When I was applying to divinity school, I heard the quote from Frederick Buechner that “the place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.”[1] I have felt this as I have learned the work of a school chaplain, where I can celebrate the diverse gifts of my students and colleagues and affirm the creative work of making worship authentic. Mary Oliver wrote, “My work is loving the world.”[2] I feel this work deeply in my calling to sit with colleagues, parents, and young people, to listen, to hold with them what needs to be held, to laugh, to grieve, and to embrace life.

Nancy: I am still trying to figure this out. I give a lot of blessings, both in writing and in person. I can also organize stuff and get things done. This is really useful in church work. A few years ago, I had the idea that I wanted to create an interfaith service for Pride in my city. The main organizer for Pride was initially hesitant about a religious service, but he attended our event and had a good experience. Since that first event, I have been asked to coordinate a similar event for Pride every year. My get-stuff-done gifts have allowed me to build relationships of trust in the community. My congregation looks forward to demonstrating support for our local LGBTQ+ community each year. Pride has become an essential outreach event for our group.

Katie: I think I have spiritual gifts of communication and teaching. I have always been interested in writing and gravitated naturally toward a career in marketing and communications after college, where I’ve worked for about the last fifteen years. To a large extent, my current position in communications and innovation at Luther Seminary is a very meaningful expression of my ministry because I have a chance to help leaders develop more life-giving practices of forming Christian community and faith. I feel called to help reshape the public conversation around Christianity so that we can repent of what often amounts to petty and destructive tribalism in order to live into the liberating and world-expanding gospel of Jesus.

Jennifer: I think gifts change over the course of one’s life, and the kinds of gifts I previously needed, I don’t have much interest in anymore. These days I see my gifts in three areas. First, I know how to be with people in their grief. I will mourn with those who mourn. Second, I can help people escape from shame. Shame always destroys. Somehow, I see people’s shame and know how to help them out of it. I think Jesus did this a lot—helped people to see the God-given goodness in them. Third, I am on the lookout for the ones who are alone, lonely, left out, and sad. I find ways to include them and let them know the joy of feeling part of a group that accepts them.

What has most surprised you about finding your ministry?

Brittany: I’m continually surprised at how inadequate I feel, and yet when I show up prepared and open to God’s Spirit, things seem to work out exactly how they need to be. Sometimes, I feel like I need to have all the answers or to have all my “stuff” figured out, but the work I do wrestles with and sits in the uncertainty. God always shows up in those gray areas and I’m not sure that will ever stop surprising me.

Fatimah: I am a minister at a local Baptist church. When I first began this work, local pastors from many different Christian traditions would ask me to come preach to their congregations. At first, I was concerned as I tried to explain to a kind Pentecostal pastor that I was Baptist and couldn’t preach to his congregation because we weren’t from the same denomination. He looked at me like I had two heads. It was then that I realized pastoral vetting is very different outside of hierarchical churches like the LDS Church or the Roman Catholic Church. Most Christian pastors want to know a couple things: “Is this pastor engaging and thoughtful?” and “Do they know the word of God?” The religious tradition one belongs to doesn’t really matter to them.

Katie: I’ve been surprised at how hard it is. People are difficult everywhere you go, and church people are no exception. Ministry—and, ultimately, faith itself—is about wading through human brokenness and hoping against hope that God is somehow present in the midst of it, and that God’s promises of grace, forgiveness, and bringing life from death are real, even when it seems as if there’s only chaos and despair.

If you are ordained, how did you decide to take that step? Do you see that as a break or an enhancement of your religious life as a Latter-day Saint?

Fatimah: I attended divinity school because I didn’t know what to do with the call that was rumbling inside of me. I attended divinity school to wrestle with God. So, I went, and I wasn’t on ordination track. I considered myself a religious refugee. Then, I found a place through my internships as part of my program where I shadowed two pastors, one Methodist and one Baptist. Both of those pastors would inculcate me with a vision of ordination. I cannot thank those two men enough for seeing ordination in me and speaking life of ordination into me.

Jennifer: I was previously ordained and gave it up when I joined the LDS Church. I am a recent convert (baptized six months ago) and of all the things I had to give up, my ordination was probably one of the easiest because of what I believe the nature of ordination actually is. For me, ordination is a community’s way of naming the gifts that already exist in a person. I had been displaying the gifts of a pastor for many years before my ordination. My community simply decided to make it official. Walking away from my ordination doesn’t take those gifts away from me. I am still every bit the minister that I was before, it just looks different in the cultural context of the LDS world.

I had to seriously re-contemplate this about a month after my baptism when a new LDS friend told me, rather angrily, that I had made a mistake in giving up ordination, “You walked away from what we are all fighting so hard to obtain! What have you done?!” But as I sought to discern what this could mean for me, I knew that all the gifts I have been given are still intact: compassion, a non-judgmental approach, and the ability to diffuse someone else’s shame. Those are gifts God gave me, not a church system, so no church system can take them away.

Brittany: I would not consider myself a Latter-day Saint any longer and see my ordination as a complete break from my former religious life. Ordination in Community of Christ comes as a response to the needs of the community, the giftedness of the person, and the needs of the community they will be serving. Calls are initiated by church leadership, and to be honest, I have struggled deeply with my call. I had twenty-six years of baggage, damage, and insecurities I was working through when my call came, and it came unexpectedly. I had to work through a new understanding of what ordination meant and decide if it was a responsibility I wanted to take on. Being ordained in Community of Christ in Utah means working with people who are seeking spiritual refuge. It’s difficult to completely break away from the culture here, and by being ordained, I was saying I was willing to stand in those moments of faith deconstruction with the hope of being a help and support in the reconstruction. Although I no longer consider myself a Latter-day Saint, I very much consider myself to be a disciple and follower of Jesus. My ordination has enhanced my understanding of Jesus’ message of good news to the poor and downtrodden. My ordination has taken me down a path of learning to set my own ego aside and be fully present in the moment for others. It’s given me more empathy and patience and has expanded my understanding of the importance of intention and finding a holy rhythm in life. I am more holistic and self-aware than I was before, and I try a lot harder to hold myself accountable to protect the rights and voices of the most marginalized. These things were important to me before, but through ordination, the purpose of Jesus’ mission has come alive.

Katie: It’s not possible to simply un-Mormon myself, so I’m sure my Mormon-ness will always be an important part of my pastoral identity. There are times I’m shocked at the ways in which white mainline Protestants struggle to speak about their faith even within their own families. In meetings with colleagues I’m always saying things like, “This must be my inner Mormon coming out again, but seriously?” Mormons do such a powerful job of instilling identity. And while not all of the tactics they employ to do so are healthy, there’s something very admirable about that, and I want to bring that commitment to identity and community forward into my ministry. I think that’s a gift of my Mormonism that I can share with the broader church.

How has your faith and/or spiritual practice deepened as a result of your chosen vocation?

Fatimah: I had to endure my own faith shattering. As I result, I have learned to hold my faith very tenderly; I allow it to fall apart, to grow, and to morph in ways that are unexpected because I have learned that I don’t want to hold it so tight that I can’t grow it with God. A faith that never undergoes shattering and wounding, I don’t know if that’s really faith. It’s that process that helps you to know that God is still in the midst and with you.

Jennifer: Ordination can be a real trap when it functions as a belief-limiting scenario. While I was ordained there was no freedom to explore belief beyond what was already prescribed. There were black-and-white limits to what I was allowed to believe. Ordination can be a blessing, but it also can be a straitjacket. You sign on the dotted line and must believe these things and never change. But I like to change and grow. I know how to recognize God’s leading in my life, and the day came when following truth was more important than clinging onto my ordination.

Nancy: As an LDS woman, I prayed, fasted, and read the scriptures almost obsessively. I felt that my connection to God was limited to those activities. I now engage in a lot of different spiritual practices and recognize that spiritual practice is more about intention and connection to God and self rather than any particular action. I think that this allows me to see that many activities can have a spiritual dimension. All of this has made my spiritual life richer and more fulfilling to me.

Brittany: I am much more mindful of how God moves in and through the everyday. I am not worried about being found worthy of God’s love or presence, I now understand that it is all around me and others with whom I come into contact. My ministry has become part of me. I do not stop being a minister once my workday is over. It has also shown me just how little I actually know about life and how much I rely on God and my community for support.

Katie: Leaving Mormonism and discerning a call to ministry was a decade-long series of existential crises. There were times I couldn’t bring myself to open a Bible or pray because it hurt so much. There were times that all I could do was fall on my face and cry out to God because it hurt so much. There were moments of revelation, moments of struggle, moments of anger, moments of healing. “What the hell are you doing with me?!” were words I shouted to God more than once. Through it all, God has drawn me closer, even when I wanted nothing to do with God and resisted the pull. God is faithful—even when it drives me crazy and I wish God wouldn’t be quite so faithful, God is faithful.

What do you hope to see in future generations of LDS women when they feel called to ministry?

Brittany: I hope women feel empowered to answer the call in whatever way feels best and most natural to them. Listen and trust the voice inside of you, even if it scares you. Whether that is staying in the LDS Church or finding opportunities to serve outside of the Church. I hope the LDS Church opens up more doors of ministry, but my hope is that women do not let closed doors stop them from answering God’s call.

Fatimah: My hope is that more and more women are able to live out their calls in the Church, and that the Church will grow to hold women’s calls with greater depth, expansiveness, and inclusivity. I believe in a God who can part the Red Sea and who sits with people in their greatest pain with love. I believe in a God who is a promise keeper.

Rachel: Allow yourself to feel and follow that call. Feel confident that as you are seeking God, and seeking good, that you will find comfort and joy in that journey. In the Gospel of Luke, when Mary unexpectedly found herself closest to the divine, she heard the words, “Fear not.”[3] I hope that LDS women will feel free to be as creative as they want to be, and that they will share their gifts of a passionate mind, open spirit, and loving heart. Be the voice you want to hear. God is with you.

[1] Frederick Buechner, Wishful Thinking: A Theological ABC (New York: Harper & Row, 1973), 119.

[2] Mary Oliver, “The Messenger,” Thirst (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006).

[3] Luke 1:30.

[post_title] => Mormon Women in the Ministry [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 53.1 (Spring 2020): 129–142Interview with Brittany Mangelson who is a full-time minister for Community of Christ. She has a master of arts in religion from Graceland University and works as a social media seeker ministry specialist. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => mormon-women-in-the-ministry [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-11-22 00:57:28 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-11-22 00:57:28 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=25888 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

British Latter Day Saint Conscientious Objectors in World War I

Andrew Bolton

Dialogue 51.4 (Winter 2018): 49–76

What of the Latter Day Saint movement that claimed to prophetically discern the times and seasons of these latter days and also boldly proclaimed that they were the restoration church?

[1]World War I was the founding disaster of the twentieth century. It began for Britain on August 4, 1914. Nobody at the time realised how serious it was going to be. Ultimately, the Great War involved many nations and their empires and resulted in over 8.5 million military deaths and between 6.6 and 13 million civilian deaths.[2] It ended empires, added to others, and redrew maps beginning in Europe. The maps redrawn in the Middle East still plague us with consequences today. About fifty million or more died from a devastatingly destructive Spanish flu epidemic, incubated in the wartime trenches in France and spread worldwide among many populations weakened by wartime conditions.[3] In sunny August in 1914, many young would-be soldiers and their families, in an explosion of patriotism all over Europe, were blind to the coming devastation and carnage of industrialized, mechanized, and chemicalized warfare. By Christmas 1914, 177,000 British soldiers had been killed, more than one thousand every day.[4] The romantic illusion of war was fading everywhere in Europe. Much worse was to come. After pursuing an initial policy of neutrality under President Wilson, the US entered the war on April 6, 1917, over one hundred years ago. Ironically, it was also Good Friday.

Response of Latter Day Saints in World War I

What of the Latter Day Saint movement that claimed to prophetically discern the times and seasons of these latter days and also boldly proclaimed that they were the restoration church? The founding heart of the restoration vision was restoring Jesus Christ to the very centre of our attention: “This is my beloved Son. Hear Him!”[5] In the Book of Mormon, Jesus taught again the Sermon on the Mount in all its uncompromising and radical love of enemies.[6] According to the story told in 4 Nephi, the Nephite people responded to the ministry of Jesus by conversion. With the love of God in their hearts, they lived for two hundred years in a form of peaceful Zion that parallels Acts 2:36–47. There is economic justice, the abolition of classes and “ites,” and the joy of strong families. This time ends with these words: “And they did smite upon the people of Jesus; but the people of Jesus did not smite again.”[7] The founding, original vision of non-violent Zion is in response to the crucified Christ, who taught and practiced the love of enemies.

So how did believers in the Book of Mormon’s message respond to World War I? For Latter Day Saints, conscientious objection (CO) would have been a faithful response to the founding vision of non-violent Zion, notwithstanding their earlier violence in Missouri, Illinois, and Utah.

David Pulsipher explains in an essay how criticism and suspicion of the war by LDS Church leaders changed after the US actually entered the war.[8] Larry Hunt in his biography of Frederick M. Smith, RLDS president from 1915 to 1946, describes Smith’s belligerent nationalism.[9] So after April 6, 1917, most American leaders of both churches urged a patriotic response to World War I by their members. This was done to gain acceptance by the wider American society. Enlisting, obeying the draft, and buying war bonds demonstrated that they were loyal Americans. The gospel of peace was displaced by American nationalism as old men sacrificed their young men for acceptance by the wider American society.

There are now known to be four British Latter Day Saint COs in WWI. Francis Henry Edwards from Birmingham was the youngest. He was apprenticed as an articled clerk, unmarried, and RLDS. It was his seventeenth birthday when Britain entered the war on August 4, 1914. He was nineteen when he was court-martialled at the Norton Army Barracks, Worcester, in December 1916 as a CO and sentenced initially to 112 days’ hard labour. Edwards served this punishment in Wormwood Scrubs prison, London before going before the central tribunal and being judged as an authentic CO. He then opted to be transferred to do work of national importance in Dartmoor Prison in Princetown—converted to a work centre for COs during WWI.

The other three conscientious objectors were all LDS. William Brad ley was thirty-five, married, a cotton spinner from Oldham, Lancashire, and secretary of the Lancashire congregation of the LDS Church. He went before the Oldham military service tribunal on July 7, 1916 and was exempted from combatant service and recommended for hospital work—work judged to be of national importance. George Snook, a clerk to an egg and butter merchant, was from Portsmouth, Hampshire, aged forty and married with three children when he was posted to Aldershot in the Non-Combatant Corps[10] on January 16, 1917. He was demobilised on April 30, 1919. Edmund Wilfrid Wheatley was a clerk to a road board in Richmond, Surrey, aged forty-two and married with five children. He followed the difficult path taken by Francis Henry Edwards. He too was court-martialled, though in Wimbledon, London, and sentenced on November 4, 1917 to two years’ hard labour. He was also sent to Wormwood Scrubs prison in London. He too came before the central tribunal and was finally adjudicated to be a genuine CO on January 4, 1918, and then sent to the Wakefield work centre in Yorkshire.[11]

More Latter Day Saint COs have come to light recently thanks in part to the tireless work of Jay Beaman, who, like Cyril Pearce in England, is compiling a database of all COs in the US and Canada. Charles Dexter Brush was twenty-eight and married with one child in 1917, RLDS and a farmer, with a fifth-grade education, living in Buffalo, Missouri.[12] British-born LDS member Albert White had migrated to Salt Lake City in 1909 at the age of eighteen. He was a conscientious objector in 1917, aged twenty-six, married with two young children.[13] George Amos Grigsby was a Canadian LDS member in Toronto and married when he called up in January 1918 and sent to France as a non-combatant.[14] In Germany there are no visible COs. Five hundred LDS men in Germany were immediately conscripted in 1914 and eventually seventy-five were killed. However, Karl Eduard Hofmann, former Social Democrat, was a reluctant soldier who had no intention of killing anyone. He was able to do medical work until he lost a leg from a lobbed grenade while tending a patient.[15] Until September 2017, there was only one known Latter Day Saint CO: RLDS F. Henry Edwards. Now, if we include Grigsby and Hoffman, there are eight, with still more perhaps to be found.[16]

Why so many British Latter Day Saint COs from small national churches? Leaders of both churches were critical of WWI before the United States entered it. Edwards, Bradley, and Snook all took their CO stand before the US entered the war on April 6, 1917, when they notionally still had the support of their American church leaders. It is important to remember that the war in Europe lasted over four years, but for the US it was over in one-and-a-half years. The hellish reality of the war was well understood by ordinary British working people. In the US, many people still had romantic ideas about the war. The WWI conscientious objection story of Francis Henry Edwards is the best known and documented at this time. It is Edwards’s story that I now want to tell, leaving competent LDS historians to work on the newly discovered British, American, German, and Canadian LDS conscientious objectors. Patrick Q. Mason, in his 2018 Mormon History Association presidential address, has already made a helpful beginning. Telling the story of F. Henry Edwards will also help others know where to begin looking for more information on the other British LDS and RLDS conscientious objectors.

The Conscientious Objection Story of Francis Henry Edwards

Unlike continental armies in Europe and elsewhere at the time, the British Army was a volunteer force. The British Army up to this point had always been small, since the English Channel and the greatest navy in the world protected the British Isles from possible invasion. Initially there were plenty of volunteers responding to the patriotism and nationalism of WWI to supply the army, and conscription was not introduced until early 1916.

Francis Henry Edwards was a member of the Birmingham RLDS congregation. He was familiarly known as Frank. Later, he adopted F. Henry as his formal name. Frank, a serious seventeen-year-old, wrote a letter dated February 13, 1915 to his church’s international magazine, The Saints’ Herald.[17] After sharing his conviction about the church, he continued to write: “I think that in this work we cannot do too much. My fellow countrymen are making great sacrifices for their king and country, and I want to be willing to give my life, if need be, for my King, the King of kings, and for the establishment of his kingdom—to be a patriot in the great sense.”[18] In his first recorded statement of conscience, he stresses his commitment to a greater patriotism. He wrote this a year before conscription was introduced in Britain.

Edwards was born into an RLDS family in Birmingham. His father had been an inactive Mormon, or Latter-day Saint. His parents were baptised into the RLDS Church on April 6, 1883. Their church life was central to the family and shaped F. Henry as he grew up. He was baptised November 3, 1905 at the age of eight years old. He fell and broke his teeth at the age of eight or nine and did not get dentures until he was a teenager. He suffered in school and was very self-conscious about how he looked.[19] Perhaps this gave him a greater sense of empathy for others as victims. His faith included teachings about the worth of all souls in the sight of God and the kingdom of God on earth, or Zion.

The RLDS Church had an international presence in nine countries at this time and had just officially been established in Germany in 1914.[20] To consider killing a German soldier who was possibly a church member would be a grave difficulty given the close, loving fellowship enjoyed by RLDS Church members. Every communion service included a re-covenanting to keep the commandments of Jesus Christ. Love your neighbour as yourself and love your enemy could be considered such commandments. F. Henry’s motivation for being a CO is stated to be religious in his records. However, his faith included an international patriotism, and he was as strongly for economic justice as any member of the democratic socialist Independent Labour Party of his time. F. Henry grew up in a working-class home, and he had to be very careful with money later in life as well. He was always in solidarity with other working-class people. His son Paul described how he was very generous in his tips to restaurant staff and anyone doing work on his home—something he and his brother Lyman also inherited as a practice.[21]

F. Henry was called to the priesthood the next year and ordained a priest on April 27, 1916.[22] He could preach, teach, and was pastorally responsible for families. He had as much sacramental authority as a priest in the Church of England or Roman Catholic Church. However, in the tradition of his denomination, he earned his livelihood not by ministry but by employment in another job. F. Henry was an articled clerk (apprentice) in a chartered accountants’ office, training to be an accountant.

Road to Conscription in WWI Britain

The road to conscription was in stages. In July 1915, Parliament passed the National Registration Act, requiring all people between fifteen and sixty-five to be registered. This enabled the government to identify men who had not yet volunteered. Military recruiting officers then visited the homes of all men aged eighteen to forty to put pressure on them to enlist. This, however, was still not enough. On January 27, 1916, conscription was introduced in Britain through the Military Service Act. Implementation started February 3, 1916. From March 2, all unmarried men aged eighteen to forty-one could be called up for military service,[23] including F. Henry Edwards. Married men were included a few months later.[24]

There was opposition to both the National Registration Act and the Military Service Act, but people were imprisoned for speaking out or for refusing to be conscripted. Any publication that might dissuade men from joining the armed forces was liable to be seized, even biblical materials. As Leyton Richards notes, “Twenty thousand copies of the Sermon on the Mount (printed without comment as a leaflet) were ordered by a magistrate in Leeds to be destroyed as seditious literature, and their would-be distributer was committed to jail under a sentence of three months’ hard labour.”[25]

The Military Service Act contained a provision for conscientious objection, and F. Henry was one of around twenty thousand British conscientious objectors in WWI.[26] Of this number he was also one of about six thousand sent to prison.[27] Although many COs were treated quite well in civilian prisons, those in the hands of the army suffered terribly. Seventy-three British COs died either in prison or as a direct result of their incarceration. Thirty-one went insane from their treatment.[28]

In May 1916, forty-two resisting COs, later called the “Frenchmen,” were sent to France to serve in the army without first being able to tell their relatives or friends.[29] They were warned that if they continued to resist, they would be shot. Suffering intimidation, harsh treatment, and continuing threats, this group of COs did not yield. Messages arrived to family and questions were raised in Parliament by sympathetic members of Parliament. A Quaker journalist and Baptist pastor F. B. Meyer were able to investigate what was happening in France and interviewed the men. In the period of June 7–24, 1916, thirty-five of the men were tried by the field general court martial. On Thursday, June 15 on a large parade ground, the sentences of the first four were announced: “The sentence of the court is to suffer death by being shot.” Pause. “Confirmed by the Commander in Chief.” Long pause. “But subsequently commuted to penal servitude for ten years.”[30] The other thirty-one had their sentences announced in two later similar ceremonies.[31]

Facing Tribunals, Court Martial and Prison]

So in going down the path of conscientious objection, F. Henry Edwards was not choosing an easy way. He did not know if he might be shot in France by British soldiers. First, F. Henry faced a borough council tribunal in Birmingham in order to present his case for being a conscientious objector. He was not successful in demonstrating he was genuine. Second, there was an appeal tribunal, but again F. Henry was not successful.[32]

The Military Service Act 1916, making conscription legal, was fair in its intentions about protecting the rights of sincere conscientious objectors. The implementation of the tribunal system, however, was not well done. Tribunal members were often biased against COs. Hearings were brief. The tribunals, though a form of court, usually did not have experience in following legal procedures or understanding due process. A military representative, a retired army officer or a recruitment officer, was also party to the tribunal, and his role was to argue against any CO claim and, if necessary, appeal the decision of the tribunal if CO status were granted. So, it is no surprise that F. Henry was twice refused conscientious objector status.[33] We do not know the tribunal details for F. Henry Edwards, since all records were destroyed after WWI (with the exception of the county of Middlesex).[34] We do know, however, that he chose not to yield to the tribunals’ denial of CO status but to resist.

F. Henry was likely arrested at home in December 1916 by a local policeman. He would normally have come before a magistrate’s court and be fined forty shillings (two pounds), nearly two weeks’ wages in a working-class job. We also know that he was handed over to the army—the Worcester Regiment, 96 Training Reserve Battalion, at the Norton Army Barracks, on December 10, 1916.[35] On the same day, as a conscientious objector, he refused both to sign and submit to a medical examination to determine whether or not he was fit for service.[36] Two days later on December 12, he was charged with the offence of “disobeying a lawful command given by his superior officer.” His army records show that F. Henry’s offence was witnessed by Sergeant J. Smith and Sergeant B. Haul. He was kept in the guard room for eight days. On December 21, 1916, F. Henry was court-martialled and sentenced to 112 days’ imprisonment with hard labour (see Fig. 2).[37] The sentence was confirmed two days later, and he was committed to the Wormwood Scrubs prison in London.[38]

Prison and Afterwards: Wormwood Scrubs and Princetown

In Wormwood Scrubs prison, many prisoners sewed mail bags alone in their prison cells. With some six thousand COs in prison by mid-1916, largely because of tribunals’ arbitrary refusal of exemption, there was a scandal in Parliament and the press. This led to devising the Home Office Scheme for COs. All imprisoned COs would be specially interviewed by the central tribunal, which was originally set up under the Military Service Act as a final court of appeal for exceptional cases. This tribunal would have the discretion to decide whether a particular CO was, after all, “genuine.” For this purpose, the central tribunal would convene in Wormwood Scrubs prison (to which COs imprisoned elsewhere would be brought), and those COs found “genuine” would be offered the opportunity to perform civilian work under civilian control in specially created Home Office Scheme work centres.[39]

On January 30, 1917, Edwards appeared before the central tribunal, a panel of two: Lord Richard Cavendish and Sir Francis Gore—two aristocrats to judge whether a working-class boy from Birmingham was a genuine CO. It would have been intimidating. Edwards successfully persuaded them that he was a genuine CO.[40] One option then before F. Henry was to accept the Home Office Scheme of doing work of national importance at a work camp like Dartmoor or Wakefield. To serve the purposes of the Scheme, those two prisons had legally been decommissioned. COs had freedom to go out in the evenings and on Sundays and to wear ordinary clothes. It meant, however, continuing on the list of the army reserve. Absolutists, refusing any cooperation with the army, did not accept the Home Office Scheme and suffered repeated court-martials and imprisonment and could have a very difficult time.

Edwards, however, was not an absolutist, and he accepted the offer of the Home Office Scheme. On March 9, 1917, he was transferred for employment by the Brace Committee at the work centre in what had been His Majesty’s Prison Dartmoor but was now Princetown Work Centre.[41] The Dartmoor prison was originally set up to hold French prisoners during the Napoleonic War and then Americans during the War of 1812.[42] Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes book The Hound of the Baskervilles is set in Dartmoor and refers to the prison. At 1,430 feet and surrounded by the gloomy moor, it is a fitting, dismal place for a prison. However, for the COs, conditions were much better here than in prison. Edwards’s contribution to work “of national importance” was serving in the kitchen, making cocoa, and baking bread and fruit pies for his fellow inmates.[43] Paul Edwards, his son, said that his cocoa was awful and the fruit pies not much better, so he did not become a skilled cook during his time at Dartmoor.[44] Others moved stones out of fields, worked in a granite quarry, gardened to feed the inmates, and other tasks. Classes were available in the evenings, taught by qualified COs, after a nine-hour work day and included English, French, shorthand, logic, and many others. F. Henry was proficient in shorthand—perhaps he learned it at Dartmoor.[45] There were about one thousand COs at Dartmoor, one quarter of whom were religious, while the rest were socialist and political objectors. In some ways, it was almost a university for COs. The Bishop of Exeter, however, would not let any of the COs use the chapel. If they had been normal criminals or murderers they would have enjoyed the grace of the Church of England, but COs were rejected. There were only a few work centre warders. The COs basically ran the work centre themselves.[46]

F. Henry Edwards went to the RLDS congregation in Exeter on Sundays on a bicycle bought by the congregation.[47] It was about twenty seven miles each way, downhill going to church, uphill on the way back. The whole ride would have taken five-and-a-half to six hours. His family reported two difficulties for him during this time. On one occasion when visiting a nearby town, perhaps Plymouth, from the work centre, he and a few other conscientious objectors were apparently taunted and beaten up by some sailors in an attempt to compromise their nonviolence. He did not fight back. At another time, while out of the work centre on a pass, he was asked to leave a cinema because several people strongly objected to his presence.[48]

Support by Community, Quakers, and No-Conscription Fellowship

Cyril Pearce describes the communal support of COs in the industrial Yorkshire town of Huddersfield.[49] In Leicester, less than an hour from Birmingham, Malcolm Elliott also tells the same story of communal resistance to the war and conscription.[50] There were over six hundred COs from Birmingham, and no doubt Edwards also found local communal support.

On August 28, 1917, Edwards was visited by a group of Quakers in Dartmoor, and in brief notes held in the Quaker archives at Friends House in London the visitor reported dates of Edwards’s court-martial and his 112 days in Wormwood Scrubs prison. The Quakers also noted that Edwards was currently being held at Princetown, Dartmoor.[51] F. Henry’s son Lyman reported that F. Henry had said he would have been a Quaker if he had not been RLDS.[52]

The No-Conscription Fellowship was the leading anti-conscription organization in Britain. It is likely that F. Henry had contact with the No-Conscription Fellowship.[53]

Compromised Support by the RLDS Church

What support did Edwards’s church give him? His motivation was, after all, religious.[54] John Schofield, district president, went with Edwards to support his claim of CO status at the tribunals.[55] Edwards’s family and friends supported him, although there were issues in the Edwards’ home congregation in Birmingham. However, what did RLDS Church leaders think of the war?

At the outbreak of the war in 1914 the RLDS First Presidency had supported US President Wilson’s positon of neutrality twice in The Saints’ Herald magazine editorials.[56] Joseph Smith III had taken the RLDS Church in a peace direction in his fifty-four-year ministry from 1860–1914.[57] The RLDS Church had members of British and German heritage in the US, and the church in Germany had officially begun in 1914. After Joseph III’s death in December 1914, Frederick M. Smith became president of the church the next year and his administration led the church through both World War I and World War II. He, like many other religious leaders, was caught up by the nationalist feelings of the time. As Sydney E. Ahlstrom wrote about the United States: “The simple fact is that religious leaders—lay and clerical, Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant—through corporate as well as personal expressions, lifted their voices in a chorus of support for the war.”[58]

Frederick M. Smith believed that if a man were conscripted he should go and do his duty. In both World Wars he was a vigorous US nationalist. He disparaged pacifists as “cowardly slackers” and would not allow them to speak their position from the pulpit.[59] His ethic about war was a nationalist ethic. This is arguably an inadequate ethic for a world war and an international church. He did not see that obeying it could result in German and British church members killing each other, but most other Christian leaders at the time did not see that as a problem either. So, from the president of the RLDS Church, Edwards would have had no moral support. Regardless, Frederick M. Smith did not articulate his position on COs until after the United States had entered the war, and by that time, Edwards was already in the Princetown Work Centre in Dartmoor.

Back in Britain, in his home congregation in Birmingham, some members harassed the Edwards family when they sat down to worship by singing “God is marshalling his army” and adding the line, “We will have no cowards in our ranks.” This created some tension at the time.[60]

After Princetown Work Centre

The Great War ended on November 11, 1918. Edwards was in the Princetown Work Centre, Dartmoor for around two years from March 1917 until the Home Office Work Scheme ended and the work camp was closed in April 1919.[61] He was released from the army reserve as part of

the military demobilization a year later on March 31, 1920.[62] Edwards went back to work at the accountants’ office. However, some clients did not like that he had been a conscientious objector in the war, and his employment ended. Continuing to be involved in volunteer church work, he became secretary of the RLDS British Isles Mission. Sometimes, when preaching, congregational members would walk out in protest against his CO stand. However, in the end most came to accept his ministry.[63]

RLDS Church Leader

In April 1920, Edwards was ordained an elder and also entered general church appointment as a missionary elder in the Birmingham and London districts. Practically, he spent most of his time at St. Leonard’s, London. He supported leaders as a secretary, continued his work as British mission secretary, served as historian, and kept church statistics.

Then RLDS President Frederick M. Smith came to Britain on a long missionary visit. He needed secretarial help, and F. Henry was asked to serve. He could, after all, do shorthand. Conscientious objector Edwards and American nationalist President Frederick M. Smith met. One imagines it could have been a very awkward encounter for both of them. Edwards tells the story of how it began: “I went to his room the first time in fear and trembling, but soon found that he was kindness personified. When I ‘settled in’ a little, I even ventured a question or two. . . . For me, it was like a course in church administration.”[64]

A warm relationship developed between the two. Edwards went to the United States in September 1921 and studied at the church’s Graceland College for a year in the religious education program.[65] Then a year later, at the age of twenty-five, he was called by Frederick M. Smith to the Council of Twelve Apostles and ordained at general conference on October 13, 1922. He immediately became secretary to the Council of Twelve and served in this role until 1946.

Edwards was then called to be a president of the church and counsellor to the new Prophet-President, Israel A. Smith, until the latter’s tragic death in 1958.[66] Edwards continued this role for W. Wallace Smith, who took over as Prophet-President after the death of his brother. Edwards left the First Presidency in 1966 after serving in a very significant way as an RLDS Church leader for over forty-four years. He finally retired in 1972 after serving over fifty years in full-time church ministry. He spoke French, Spanish, and passable German.[67]

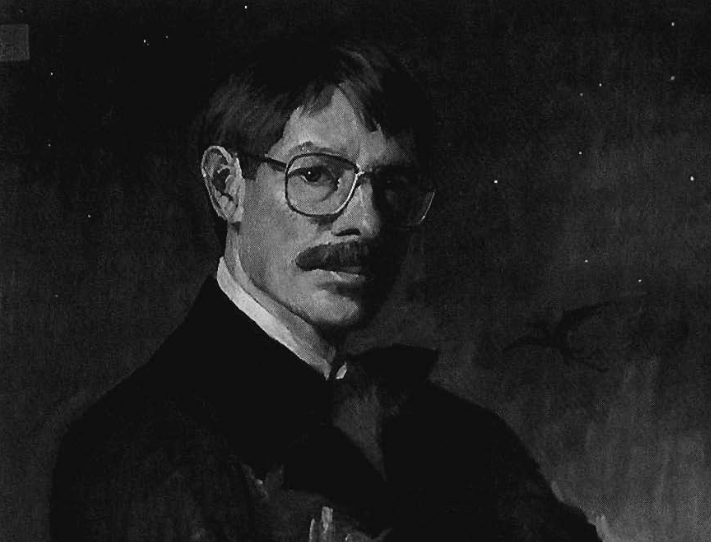

Edwards was a very able administrator and perhaps the most prolific writer in the whole Latter Day Saint movement—penning over five hundred articles and over three dozen books and texts.[68] Paul Edwards called his father “articulator for the church” and used this phrase as the title for the short biography that he wrote about him.[69] F. Henry’s last book, The Power that Worketh in Us, was published when he was over ninety years old. His writing was accessible, well-expressed, and deeply Christian. Edwards did not have a college degree, was largely self-taught, and his writing contributions, which he continued in retirement, were significant.

One of his last Saints Herald articles, published in September 1985, was titled “Let Contention Cease” and written just after the RLDS Church had made the decision to ordain women.[70] There was uproar from conservatives. Edwards was clear that he did not intend to end debate. Debate was important. However, what was also important was how the debate about this, and other issues, was carried out. Was it done in love and with mutual respect? To the end, Edwards still believed in peacemaking.

Edwards became a US citizen with some reluctance at the beginning of World War II so he could continue to serve on the board of the church’s radio station.[71] Alexander Smith, younger brother of Frederick M. Smith, was a federal judge and enabled F. Henry to take a modified citizenship oath in a private ceremony so he would not be promising to take up arms against Britain or others. Despite losing a good friend on the USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor, he objected to selling defense stamps in Sunday School.[72]

It is interesting that Edwards was careful not to go out on a limb publicly on causes like pacifism or civil rights for Blacks, although he believed strongly in both. As a minister he wanted to have long-term influence with people, to keep the door open for further conversation. It could be argued that it was a strategy with integrity.[73]

Edwards’s Korean War veteran son, Paul, summed up his dad’s stand on peace in these words: “A particular note should be taken of Frank Edwards’s lifelong advocacy for peace. But, in all fairness, it was more than that: it was the abhorrence of war. Edwards not only disagreed with the concept of war as a political tool among nations, he condemned the absurd waste of human potential and the destruction of both human life and human values as well.”[74]

Family

In 1924, F. Henry married Alice Smith, President Smith’s daughter. Alice, a Stanford graduate, was more than equal intellectually, and her own inner strength tempered Edwards’s “in-charge” tendency. They were married for forty-nine years and had two sons, Lyman and Paul, and an adopted daughter, Ruth. Edwards was a good husband and a loving father, and both his sons speak with affection about their dad. He missed Alice terribly when she died. When his daughter, Ruth, died, he also took that very hard. Both sons affirm that F. Henry never changed his mind about the folly of war or regretted the rightness of his WWI conscientious objection stand.[75]

The Significance of F. Henry Edwards’s Stand as a Conscientious Objector

In his book The First World War, British military historian John Keegan writes, “The First World War was a tragic and unnecessary conflict.”[76] Unnecessary because the conflict between Austria and Serbia was a local conflict and because the war could have been prevented. Tragic because more than seventeen million people died, and it set up the conflict that would result in World War II. If ever a war was unjust and stupid, it is the First World War. It was fueled by nationalisms that practiced human sacrifice on a huge, industrialized scale. Is it apostasy for patriotism to displace the gospel, for the president or prime minister to nullify the voice of Jesus, for national laws to replace the commandments of Jesus?

So, with hindsight, F. Henry Edwards’s stand, and that of the three other British LDS conscientious objectors, looks prophetic, courageous, and righteous. He did not worship at the altar of British nationalism, nor later at the altar of American nationalism. He did not run away. He did not hide. He was upfront in his witness of resistance. It was an act of civil disobedience for which he suffered the consequences as did Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.[77] In faithfully seeking to follow the ways of Jesus, his stand was later vindicated. In Britain, more RLDS men followed Edwards in WWII as COs even though President Frederick M. Smith in the US was against this position. Perhaps Edwards, as more people learn about his story, can also inspire the growing peace mission of Community of Christ today.

The lives of F. Henry Edwards and subsequent British RLDS COs in WWII—most of whom I personally knew—also say something very important to me. They were not only against an evil, that of killing a fellow human being, they were for something more—a world where every family could live “beneath their own vine and fig tree and live in peace and unafraid.”[78] Their later years of loving, skilled, dedicated service testifies to the authenticity of their earlier witness. If they were against war it was because they were for the peaceable kingdom of God on earth, and in baptism they had given their lives fully to that. Their lives were also poems of a just spirit, lived out, incarnated. Their witness should not be dismissed.

How are we to be COs today? I look to a day when there will be enough conscientious objectors to not only close down war as a way of solving conflicts but to abolish nuclear weapons, end climate change, poverty, racism, sexism, and injustice of all kinds. Believers in Zion can do no less. Am I willing to be a conscientious objector against evil in my day as I live for the King of kings and the kingdom? Love of country is too small a love, and that is why it is a form of idolatry. “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son.”[79]

The author would like to acknowledge: Peter Judd for finding and sharing key primary source documents on Edwards and for an unpublished essay, “RLDS Attitudes Toward World War I.” Bill Hetherington, archivist for Peace Pledge Union in London, who through an interview and lengthy emails very generously helped me understand conscientious objection in WWI Britain and helped me make important corrections. Cyril Pearce and Jay Beaman for their generosity of time, expertise, and CO databases for Britain and the US and Canada, respectively. I very much enjoyed the conversations with Paul and Lyman Edwards, sons of F. Henry Edwards. Finally, the author is grateful for the collegial sharing, encouragement, and good fellowship with LDS scholars David Pulsipher and Patrick Mason.

[1] Before changing their name to Community of Christ in 2001, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS Church) stylized this term as “Latter Day Saint,” while The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) stylizes it as “Latter-day Saint.” The references throughout this paper will be consistent with whichever organization is being discussed, and “Latter Day Saint” will be used when referring to both.

[2] “Source List and Detailed Death Tolls for the Primary Megadeaths of the Twentieth Century,” Necrometrics, http://necrometrics.com/20c5m.htm#WW1. There is a consensus around 8.5 million military deaths. Civilian death estimates range from 6.6 million to 13 million depending on whether the Russian Civil War and the Armenian massacres are included.

[3] Jeffery K. Taubenberger and David M. Morens, “1918 Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 12, no. 1 (Jan. 2006): 15–22, available at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/12/1/pdfs/05-0979.pdf.

[4] Oliver Haslam, Refusing to Kill: Conscientious Objection and Human Rights in the First World War (London: Peace Pledge Union, 2014), 16.

[5] Joseph Smith—History 1:17. See also The History of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, vol. 1, 1805–1835 (Independence, Mo.: Herald, 1951), 9.

[6] LDS 3 Nephi 12:19–26, 38–48; RLDS III Nephi 5:66–75, 84–92. Compare with Matthew 5:21–26, 38–48.

[7] LDS 4 Nephi 1:34; RLDS IV Nephi 1:37.

[8] J. David Pulsipher, “‘We do not love war, but . . .’: Mormons, the Great War, and the Crucible of Nationalism,” in American Churches and the First World War, edited by Gordon L. Heath (Eugene, Ore.: Pickwick, 2016), 129–48.

[9] Larry E. Hunt, F. M. Smith: Saint as Reformer, vol. 2, 1874–1946 (Independence, Mo.: Herald, 1982), 438–43.

[10] The Non-Combatant Corps (NCC) was a corps of the British Army comprised of conscientious objectors.

[11] Credit for the discovery of these three LDS conscientious objectors belongs to Cyril Pearce, a premier scholar of British World War I conscientious objectors.

His database “CO Register VII Access 2010.mdb” was sent to me Sept. 20, 2017, and all four Latter-day Saint COs are included. As of that date he had 18,328 entries. However, Pearce continues to add to the database. An older version of Cyril Pearce’s registry is available online through Imperial War Museums. This version is now out of date by two years. It has 17,426 documented conscientious objectors and includes Francis Henry Edwards and Edmund Wilfrid Wheatley but not William Bradley or George Snook. This older public registry is available at https://search.livesofthefirstworldwar.org/search/world-records/ conscientious-objectors-register-1914-1918.

Edmund Wilfrid Wheatley came before central tribunal with Lord Richard Cavendish and Lord Hambleden on Jan. 4, 1918. Lord Richard Cavendish was a member of the central tribunal who reviewed Francis Henry Edwards a year earlier. See the central tribunal minutes for the meeting held on Jan. 4, 1918. These minutes can be downloaded from First World War Military Service Tribunals, National Archives, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/conscriptionappeals. See also National Archives MH-47-2-2.

[12] Draft Registration Card for Charles Dexter Brush, form 314, no. 18. It is held under the volume label 25-32 A at the NARA (National Archives) in Morrow, Georgia, for the draft board ledger for Brush’s home county in Missouri in 1917.

[13] Patrick Q. Mason, “‘When I Think of War I Am Sick at Heart’: Latter-day Saint Non-Participation in World War I” (presidential address, Mormon History Association 53rd Annual Conference, Boise, Idaho, Jun. 9, 2018).

[14] Jay Beaman, email to author with documents, Sept. 5, 2018.

[15] Mason, “When I Think of War,” 3, 10–11.

[16] Arguably, Canadian George Amos Grigsby, as a non-combatant, was a CO. German Karl Eduard Hofmann did not have a legal right to be a CO in Germany, unlike Britain, Canada, and the US. He, like a number of others in the German army, were closet COs in WWI, quietly refusing to hurt anyone, and demonstrated by Hoffman in getting medical duties.

[17] The publication was called The Saints’ Herald from 1877–1953. It changed to Saints’ Herald in 1954, then to Saints Herald in 1973. Since 2001, the publication's official name is Herald. References to the periodical throughout this paper will use the name that was in use at the time.

[18] Francis Henry Edwards, letter to the editor, Birmingham, England, Feb. 13, 1915, published in The Saints’ Herald, May 12, 1915, 40.

[19] Paul M. Edwards, interview, Jun. 29, 2017.

[20] Council of Twelve Apostles, “Establishing the Church in New Nations,” Official Policy, revised May 4, 2014, 11.

[21] Paul M. Edwards, interview, Jun. 29, 2017.

[22] Summary in F. Henry Edwards’s biographical file in Community of Christ Archives, Independence, Mo. See also Paul M. Edwards, Articulator for the Church (Independence, Mo.: Herald, 1995), 17.

[23] In American English, drafted. However, the US term “drafted” is never used in Britain. Bill Hetherington, Peace Pledge Union Archives, email to author, Jun. 20, 2017.

[24] This paragraph draws from Haslam, Refusing to Kill, 21–27.

[25] Leyton Richards, The Christian’s Alternative to War, 4th ed. (London: SCM, 1930), 89.

[26] The online Cyril Pearce registry hosted on the Imperial War Museums’ “Lives of the First World War” has 17,426 documented conscientious objectors, including F. Henry Edwards; see https://search.livesofthefirstworldwar.org/search/world-records/conscientious-objectors-register-1914-1918. Note that access to the full records requires creating a free account. Bill Hetherington, interview, Mar. 13, 2017. He estimates that there are around twenty thousand COs altogether.

[27] Haslam, Refusing to Kill, 38.

[28] David Boulton, Objection Overruled: Conscription and Conscience in the First World War (Hobsons Farm, Dent, Cumbria: Dales Historical Monographs, 2014), 11. See page 266 for a list of names of the seventy-three who died. For a longer discussion of those who went insane, see page 258.

[29] Earlier, Bill Hetherington had estimated fifty in this group. Since then he has been able to identify by name all the “Frenchmen” and he is satisfied the number was exactly forty-two (email to author, Jun. 20, 2017).

[30] Felicity Goodall, A Question of Conscience: Conscientious Objection in the Two World Wars (Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton, 1997), chap. 3.

[31] Bill Hetherington, email to author, Jun. 20, 2017

[32] Bill Hetherington, interview, Mar. 13, 2017. After the war, tribunal records were destroyed for the sake of space. Tribunal records for Middlesex (the county west of London) were kept in order to demonstrate how the system worked. So, while F. Henry Edwards’s tribunal records are not available, the system that he went through is well understood.

[33] Haslam, Refusing to Kill, chap. 3.

[34] Bill Hetherington, interview, Mar. 13, 2017.

[35] “New Soldier’s Record,” Francis Henry Edwards 17120: Record of Service, 3. I am grateful to Peter Judd for finding this on the internet: http://www.greatwar. co.uk/research/military-records/british-soldiers-ww1-service-records.htm.

[36] Ibid. See also Francis Henry Edwards’s records (specifically, the war service comments) in the Conscientious Objectors Register, 1914–1918, hosted by the Imperial War Museums, https://search.livesofthefirstworldwar.org/search/ world-records/conscientious-objectors-register-1914-1918.

[37] “New Soldier’s Record,” Regimental Conduct Sheet, 7.

[38] “New Soldier’s Record,” Statement of the Service of No. 17120, 9.

[39] Bill Hetherington, email to author, Jun. 20, 2017. I am grateful to Bill Hetherington for this paragraph.

[40] See the central tribunal minutes for the meeting held on Jan. 30, 1917. These minutes can be downloaded from First World War Military Service Tribunals, National Archives, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/conscription-appeals. See also National Archives MH-47-1-3.

[41] “New Soldier’s Record,” Statement of the Service of No. 17120, 9.

[42] Wikipedia, s.v. “Princetown,” last modified Apr. 4, 2018, https://en.wikipedia. org/wiki/Princetown.

[43] Edwards, Articulator for the Church, 17.

[44] Paul M. Edwards, interview, Jun. 29, 2017.

[45] Felicity Goodall, A Question of Conscience, 48.

[46] Ibid., 44.

[47] I heard this from Frank Wilson, an eighty-four-year-old church member with whom I stayed as an RLDS missionary in 1977.

[48] Keith Allen, interview, Mar. 4, 2017. Paul M. Edwards told me about the cinema story in an interview in Aug. 1997.

[49] Cyril Pearce, Comrades in Conscience: The Story of an English Community’s Opposition to the Great War (London: Francis Boutie, 2001).

[50] Malcolm Elliott, “Opposition to the First World War: The Fate of Conscientious Objectors in Leicester,” Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society 77 (2003): 82–92.

[51] David Irwin, email to author, Mar. 2, 2017. Case No. 3610 held in the Visitation of Prisoners Committee files (YM/MfS/VPC, box 3, file 4) at Library of the Religious Society of Friends, Friends House, 173–77 Euston Road, London NW1 2BJ.

[52] Lyman Edwards, interview, Jul. 3, 2017.

[53] Conscientious Objectors Report LXII, Jan. 5, 1917 (Information Bureau, 6, John Street, Adelphi, London, WO). This was a publication of the No-Conscription Fellowship. Edwards is reported as one of nine arrested from Birmingham.

[54] See the Conscientious Objectors Register, 1914–1918, hosted by the Imperial War Museums, https://search.livesofthefirstworldwar.org/search/world-records/ conscientious-objectors-register-1914-1918.

[55] Franklin Schofield told me this story about F. Henry and his father, John Schofield, in the early 1990s.

[56] “Neutrality Enjoined,” The Saints’ Herald 61, no. 37, Sept. 16, 1914, 873; “Caution Enjoined—A Second Warning,” The Saints’ Herald 61, no. 45, Nov. 11, 1914, 1065.

[57] Lachlan Mackay, “A Peace Gene Isolated: Joseph Smith III,” John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 35, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2015): 1–17. This is a good overview of Joseph Smith III’s peace direction.

[58] Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1972), 884.

[59] Frederick M. Smith was a strident nationalist in World War I like many other leaders and members in other denominations in this period. At the outbreak of World War II, Frederick M. Smith’s editorial “Our Attitude to War” (The Saints’ Herald 86, Nov. 18, 1939, 1443) argues an ethic of obeying the law of the land in terms of conscription. He also argued against conscientious objection in this editorial and other writings. Peter A. Judd in an unpublished essay, “RLDS Attitudes Toward World War I” (Saint Paul School of Theology, Feb. 24, 1975) describes well the change within the US church from “a position of strict neutrality in 1914 to a position of unqualified support for the United States and allied nations by 1918” (9). For a good overview of Frederick M. Smith’s nationalist attitudes from WWI to WWII, see Hunt, F. M. Smith: Saint as Reformer, 438–48.

[60] Ida Dix of the Leicester congregation told me about this trouble in the Birmingham congregation around 1996. She was a girl at the end of World War I. The hymn was by Joseph Woodward.

[61] Bill Hetherington, interview, Mar. 13, 2017.

[62] “New Soldier’s Record,” Statement of the Service of No. 17120, 9.

[63] Edwards, Articulator for the Church, 18.

[64] Naomi Russell, “Sixty-nine Years of Ministry,” Saints Herald 132, no. 15, Sept. 1985, 384.

[65] F. H. Edwards’s naturalization card.

[66] The First Presidency of Community of Christ consists of three people, the Prophet-President of the church and two counsellors or assistants. Each is called a president and it is together that they have authority to preside over the church. So, F. Henry Edwards was not the Prophet-President but a counsellor to the Prophet-President.

[67] Paul M. Edwards, interview, Jun. 29, 2017.

[68] Edwards, Articulator for the Church, 88–123. Paul lists here F. Henry Edwards’s books and articles.

[69] Ibid., 85.

[70] F. Henry Edwards, “Let Contention Cease,” Saints Herald 132, no. 15, Sept. 1985, 381–83.

[71] According to his naturalization card, Edwards became a naturalized citizen on Dec. 19, 1938.

[72] Paul M. Edwards, interview, Jun. 29, 2017.

[73] Ibid. Lyman Edwards, interview, Jul. 3, 2017. Lyman Edwards stated that his dad was not obsessive about his conscientious objector stand but was comfortable in what he had done.

[74] Edwards, Articulator for the Church, 44.

[75] Paul M. Edwards, interview, Jun. 29, 2017 and Lyman Edwards, interview, Jul. 3, 2017. Phil Caswell told me that F. Henry had told Clifford Cole that he had revised his view of conscientious objection, but this is contradicted by Paul and Lyman. Phillip Caswell, interview, May 22, 2017.

[76] John Keegan, The First World War (London: Hutchinson/Random House, 1998), 3.

[77] Henry Thoreau in his essay on Resistance to Civil Government (Civil Disobedience), published in 1849, described his act of refusing to pay a war tax during the Mexican-American War, 1846–1848. He opposed the slavery implications of this war and was imprisoned for this act of civil disobedience. This essay was a very important influence on Mohandas K. Gandhi and his non-violent resistance campaigns in South Africa and later in India. It is important to remember that Gandhi was a lawyer who respected law, but drew the important distinction between civil disobedience and criminal disobedience. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail, written Apr. 16, 1963 also articulates the moral responsibility to non-violently break unjust laws that were defending racism and segregation. Both Gandhi and King suffered imprisonment for their civil disobedience. British Latter Day Saint conscientious objectors like Edwards, Bradley, Snook and Wheatley were also acting in this tradition of civil disobedience—by refusing to be conscripted and thus refusing to kill in war.

[78] Song based on Micah 4:4.

[79] John 3:16 NRSV.

[post_title] => British Latter Day Saint Conscientious Objectors in World War I [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 51.4 (Winter 2018): 49–76What of the Latter Day Saint movement that claimed to prophetically discern the times and seasons of these latter days and also boldly proclaimed that they were the restoration church? [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => british-latter-day-saint-conscientious-objectors-in-world-war-i-2 [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-12-09 02:21:38 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-12-09 02:21:38 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=22908 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Community of Christ: An American Progressive Christianity, with Mormonism as an Option

Chrystal Vanel

Dialogue 50.3 (Fall 2017): 89–115

I thus argue that Mormonism exists wherever there is belief in the Book of Mormon, even though many adherents reject the term “Mormonism” to distance themselves from the LDS Church headquartered in Salt Lake City.

Most scholars of Mormonism focus on The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints headquartered in Salt Lake City, Utah and currently presided over by Thomas S. Monson. However, according to Massimo Introvigne, a specialist in new religious movements, “six historical branches”[1] of Mormonism developed after the death of the founder, Joseph Smith, in 1844: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints led by Brigham Young; the Reorganized Church/Community of Christ; the Church of Christ (Temple Lot); the Church of Jesus Christ organized around the leadership of William Bickerton (1815–1905); the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints that accepted James J. Strang (1813–1856) as prophet and king; and the Church of Jesus Christ that followed the leadership of Alpheus Cutler (1784–1864). I like to refer to these denominations as the “six historical Mormonisms.”[2]

As Mark Lyman Staker has shown, the terms “Mormons,” “Mormonites,” and “Mormonism” originally referred to believers in the Book of Mormon and their religion.[3] I thus argue that Mormonism exists wherever there is belief in the Book of Mormon, even though many adherents reject the term “Mormonism” to distance themselves from the LDS Church headquartered in Salt Lake City.

The plural term “Mormonisms” may have been used for the first time by Grant Underwood in 1986.[4] Since then, it has been used by sociologist Danny Jorgensen in a 1995 article on Cutlerite Mormonism[5] (following discussion with Jacob Neusner, a scholar of “Judaisms”[6]), by David Howlett in his 2014 book on the Kirtland Temple,[7] and by Chris tine Elyse Blythe and Christopher Blythe, who are editing a forthcoming book on Mormonisms.[8] My interest in the various denominations claim ing Joseph Smith as their founder came after I read Steven L. Shields’s groundbreaking book Divergent Paths of the Restoration.[9] I first used the term “Mormonisms” in 2008, while writing my master’s dissertation under the direction of Professor Jean-Paul Willaime, a sociologist of Protestantisms. Taking into account the plurality in Mormonism, I simply pluralized “Mormonism” as my professor pluralized “Protestantism.”

This paper focuses on the Community of Christ (hereafter referred to as “CoC”), known as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Days Saints (hereafter referred to as “RLDS Church”) prior to 2001. Headquartered in Independence, Missouri, the CoC has nearly 200,000 members worldwide and is the second largest movement whose roots go back to Joseph Smith. I argue that the CoC today is an American progressive Christianity with Mormonism as an option.

Research on the RLDS Church/CoC has been fruitful, though not as prolific as research on the mainstream LDS Church. Whereas nineteenth-century RLDS history tended to be defensive against other Mormonisms, especially toward the LDS Church,[10] since the 1950s it has opened itself to a more neutral academic approach, with groundbreaking studies such as Robert Flanders’s book on Nauvoo,[11] Roger Launius’s non-hagiographic biography of Joseph Smith III,[12] and the sociological studies of Danny Jorgensen.[13] The work of Richard Howard should also be mentioned, as he was the first professionally trained RLDS Church historian.[14] Mark Scherer succeeded Howard in 1994 and continued until 2016. Scherer’s three volumes on RLDS/CoC stand among the must-read books in Mormon studies because of their clarity and use of archival material, and Scherer’s research on RLDS/CoC globalization and its most recent history is groundbreaking.[15] Furthermore, the John Whitmer Historical Association, founded in 1972, publishes historical research on the RLDS/CoC by authors from diverse backgrounds (academics, amateur historians, and institutional historians that some might sometimes consider as apologetics).

This paper is based on historical and sociological research grounded in observations made during several field research trips between 2009 and 2013 in Independence, Kenya, Malawi, Haiti, France, Germany, England, and The Netherlands (while working as a translator for the CoC), the consultation of historical resources (both primary and secondary sources) at the CoC library and archives in Independence, Missouri, as well as a survey distributed to the Colonial Hills congregation (in Blue Springs, Missouri, near the Independence headquarters) on October 12, 2010.