Mother in Heaven

Introduction

Dialogue has long been a home for important scholarship on Heavenly Mother including our special issue, “Heavenly Mother in Critical Context.”

We recognize and acknowledge that theology is difficult, messy, and personal.

We hope that by entering into dialogue with each other, we will all create a better community and a better theology that reflects God, ourselves, and our collective futures.

For those currently struggling, know that we at Dialogue will struggle with you.

For those of you mourning, we will mourn with you.

Featured Issue

The Spring 2022 issue is a special one. “Heavenly Mother in Critical Context” begins with Art Editor Margaret Olsen Hemming on “The Divine Feminine in Mormon Art” and continues with Margaret Toscano’s “In Defense of Heavenly Mother: Her Critical Importance for Mormon Culture and Theology.” Other highlights include, “Guides to Heavenly Mother: An Interview with McArthur Krishna and Bethany Brady Spalding. And love the cover? It was carefully curated by Andi Pitcher Davis. You can read more about Sara Lynne Lindsay’s cover art here. The issue is full of other fascinating scholarship, as well as personal essays and poetry all in honor of Heavenly Mother.

Featured Articles

The Seeking Heavenly Mother Project: Understanding and Claiming Our Power to Connect with Her

Kayla Bach, Emily Peck, and Charlotte Scholl Shurtz

Dialogue 55.1 (Spring 2022): 169–178

Our goal is for the Seeking Heavenly Mother Project to have this empowering effect on all who participate. We see a strong need to ensure that our community is inclusive and intersectional, creating spaces wherein LGBTQ+ individuals and other members of marginalized groups can be affirmed in the knowledge that they too are created in the image of God.

If power is the ability to act, then creation is the ultimate manifestation of power. A creator is an engineer of something new, an artist of something never before seen, a musician of what has not been previously heard. Creation is not innately masculine or feminine. It is not defined by gender or channeled only through administrative practices. It is something that is ever-present in our everyday lives.

Within Latter-day Saint theology, Heavenly Mother and Heavenly Father provide a clear example of creative power by creating the universe. Eliza R. Snow proclaimed this truth boldly, that the “eternal Mother [is] the partner with the Father in the creation of worlds.”[1] More recently, Patricia T. Holland explained how together our Heavenly Parents are involved in “our creation and the creation of all that surrounds us.”[2]

Though our Heavenly Parents are both involved in creation, Latter-day Saint discourse, teachings, and rituals often leave out Heavenly Mother, thus making it difficult to see creation as a universal opportunity. For us, this imbalance is unacceptable. As we have each sought to understand our own divine nature, as well as the nature of God, the need to know, seek, and recognize our relationship with Heavenly Mother has grown stronger. For this reason, we started the Seeking Heavenly Mother Project, centered on the idea of creativity as a pathway for connection. We believe that by creating in a variety of mediums, both artistic and literary, we can connect to the Divine Mother. Additionally, our project aims to create a community of individuals seeking to know and become like Her, thus allowing our interactions with one another to serve as acts of creation in building connection and unity.

Creation as Power

For each of us, creation has been personally meaningful. It has led us to know and feel Heavenly Mother’s love on a deeper level. For Charlotte, connecting to Heavenly Mother started during her preteen years. While reading the Doctrine and Covenants, a marvelous idea came into her head. If we have a Heavenly Father, if families are so important to God, and if we are on this earth to become like Him, wouldn’t it make sense to also have a Heavenly Mother? If we have a Heavenly Mother, what is She like? When Charlotte took these thoughts to her dad, he responded that we do have a Heavenly Mother, but “it” wasn’t really something we talk about. This interaction left her feeling rebuked for asking about Heavenly Mother, and she quieted her questions for many years.

When she got married, the questions she had asked as a child returned and brought three more questions. What do the eternities look like for me, as a woman? What does Heavenly Mother do? How am I supposed to become like someone I know almost nothing about? These questions were so persistent and left her feeling so lonely and hopeless that she sat in the shower and cried. Merely knowing that Heavenly Mother exists was not enough. Without any knowledge of Her love, Her power, or anything else about Her, Heavenly Mother didn’t feel real.

Eventually Charlotte heard about Mother’s Milk: Poems in Search of Heavenly Mother by Rachel Hunt Steenblik and Dove Song: Heavenly Mother in Mormon Poetry, a collected anthology of poems edited by Tyler Chadwick, Dayna Patterson, and Martin Pulido. Both poetry books are exclusively about Heavenly Mother. Reading them gave her comfort and hope that she, too, could know Heavenly Mother like the poets whose words she was reading. Realizing that creation is a way to learn about Heavenly Mother directly motivated Charlotte to write poetry, paint pictures, and claim her authority to know and emulate Her as one of Her daughters.

Connection in Community

Like Charlotte, each of us has seen the power of creativity in connecting to our Heavenly Mother. We have been inspired to create a community where, together, we can connect and collaborate in the search for our Mother. While individually, we each have immense creative power, together, this effect is multiplied. Thus, the invitation is open to everyone to join with us by submitting art, music, poetry, essays, or experiences centered on Heavenly Mother to SeekingHeavenlyMother.com.

Already through our efforts, we have come to know others who are using their creative power to connect with our Heavenly Mother. Two of these amazing individuals are McArthur Krishna and Bethany Brady Spalding, the authors of A Girl’s Guide to Heavenly Mother. Their book pairs artwork from artists all over the world with quotations and text in order to help girls visualize their Heavenly Mother and what She means in their own lives. Its initial success inspired McArthur to coauthor a second book with Martin Pulido, edited by Bethany Brady Spalding, entitled A Boy’s Guide to Heavenly Mother. In addition to McArthur, Bethany, and Martin, we have joined with other incredible artists, thinkers, and authors to share in this journey, many of whom are featured on our website SeekingHeavenlyMother.com. Their creative contributions to our community have allowed us to gain additional understanding of our Heavenly Mother and how She relates to her children. As we encourage one another to seek our Heavenly Mother through creativity, we will feel Her love not only in our work but also in our friendships. We will feel Her love more abundantly as we strengthen our bonds as members of the human family.

The experiences we have together in community can be transformative. Emily had one such experience during her sophomore year at Brigham Young University. While taking an Indian dance class, she learned an interpretive dance about the Hindu deity Ganesh. During a section of the dance, she used her hands to imitate the blooming of a lotus flower while slowly standing up. During this process of uplifting and unfolding, she suddenly became aware of her own divine potential. She realized that regardless of what she was going through, she had the power to ascend above the turmoil and one day become divine. After this realization, she saw all the women around the room dancing in unison, all rising above their life’s confusion. She saw divinity in them. Emily felt a sense of community and kinship with the women dancing together and felt she was journeying with them to become like the Eternal Mother.

Like the community Emily found in her dance class, this project builds a community through creative works. This sense of community has the ability to encourage and enlighten others to reach for the divine. One of our key goals is to establish a safe and inclusive venue in which we can celebrate our Heavenly Mother through our own creations. Through works of creation, we can lift and influence others. We want this project to help us grow together in our understanding of the eternal connection we have with our Heavenly Mother.

Belonging with the Divine

A community has many purposes. One is to support the efforts of the individual members. The other is to support the edification of the whole. The Seeking Heavenly Mother Project is a place where anyone can go to find art, essays, music, and poetry to ponder as they seek their own personal revelation about Heavenly Mother. We desire to build a community ever growing toward Her through creative works. Through the acts of creating and witnessing others’ creations, we can build personal relationships with Heavenly Mother.

Kayla experienced how a strong personal connection to Heavenly Mother can bless and empower others while serving as a missionary in Santiago, Chile. During her mission, she developed a friendship with Constance,[3] a recent convert who had grown discouraged about her relationship with God. Kayla decided to teach her about Heavenly Mother. As she taught and as Constance gained her own belief in the Divine Mother, the question became obvious: “Why don’t we talk about Her more?” Constance wanted to know why the missionary discussions and Church lessons that had taught her the gospel had neglected to teach her about her Mother in Heaven. It seemed to her to be of the utmost importance that she had an all-powerful, infinitely loving Divine Mother. This understanding empowered her as she felt more connected to her own divine nature.

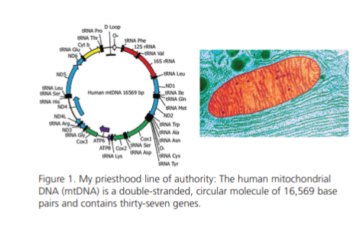

Throughout her mission, Kayla encountered others who were seeking this same sense of belonging that comes from learning about the Mother. As she shared her beliefs with them, her conviction of the importance of Heavenly Mother was strengthened. Other missionaries who served alongside her also sought reminders that they, too, were “created in the image of God.”[4] By expanding their understanding of divinity to include Heavenly Mother, they expanded their understanding of themselves. Their belief in Her helped them to claim the power they had to effect change, for as children of “divine, immortal, omnipotent Heavenly Parents,”[5] power was a part of their spiritual DNA.

Our goal is for the Seeking Heavenly Mother Project to have this empowering effect on all who participate. We see a strong need to ensure that our community is inclusive and intersectional, creating spaces wherein LGBTQ+ individuals and other members of marginalized groups can be affirmed in the knowledge that they too are created in the image of God. We want to encourage each individual to develop their own personal connection to the divine while also offering them a sense of belonging in a community of seekers where every journey is honored. By creating, connecting, and building understanding, we can support one another as we each discover our divine nature.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] John Longden, “The Worth of Souls,” Relief Society Magazine 44 (Aug. 1957): 492, 494. Quoted in David L. Paulsen and Martin Pulido, “‘A Mother There’: A Survey of Historical Teachings about Mother in Heaven,” BYU Studies Quarterly 50, no. 1 (2011): 7.

[2] Patricia T. Holland, “Filling the Measure of Our Creation,” in On Earth as It Is in Heaven by Jeffrey R. Holland and Patricia T. Holland (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989), 4.

[3] Name has been changed.

[4] “The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” Ensign, Nov. 2010, 129.

[5] Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “O How Great the Plan of Our God!,” Oct. 2016.

[post_title] => The Seeking Heavenly Mother Project: Understanding and Claiming Our Power to Connect with Her [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 55.1 (Spring 2022): 169–178Our goal is for the Seeking Heavenly Mother Project to have this empowering effect on all who participate. We see a strong need to ensure that our community is inclusive and intersectional, creating spaces wherein LGBTQ+ individuals and other members of marginalized groups can be affirmed in the knowledge that they too are created in the image of God. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => the-seeking-heavenly-mother-project-understanding-and-claiming-our-power-to-connect-with-her [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-09-23 01:11:39 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-09-23 01:11:39 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=29143 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Dear Heavenly Mother

Taisha Ostler

Dialogue 55.1 (Spring 2022): 167

I am encouraged by small changes, but change takes time. For now, I will speak your name. I will make you part of our eternal narrative. I will share your love and stop myself from looking past you. I will teach my children to see your light and be lifted by your strength, that they will speak your name as easily as they do Father’s—for both of you are part of their eternal makings.

Podcast version of this piece.

Dear Heavenly Mother,

You have been lost to me, hidden from my view behind a veil of professed sacred protection, but I am searching for you—pulling you into the light. Now that I am also called Mother, I know you are strong. I know you do not need protecting, that you are a force of love and life. I believe you have always been with me. Guiding. Directing. Giving me strength in time of need and celebrating my moments of joy. I know you were there as I pushed and breathed and bled my own babies into the world. Yet, I looked past you.

Now, I see how my self-proclaimed “daddy’s girl” attitude has been shaped by the patriarchal system that hid you from me in the first place. I do not pray to you, and until recently, hadn’t even prayed about you. Now I ask Father to help me feel your love and guidance and to understand when you are present in my life. I long to find my way into your arms, to be held up by you.

For so long, I felt unbalanced, but I didn’t understand why until others of my faith began to speak your name. Now, each time you are acknowledged, I feel righted. I see myself as a woman loved by Heavenly Parents, with an inheritance that includes the feminine divine. “Neither is the man without the woman, neither the woman without the man” (1 Cor. 11:11).

I wept when you were included (as a Heavenly Parent) in the Young Women theme, Now, when my nieces recite those powerful words, you become part of their identities. I am grateful for this, but the young men, my own boys included, repeat a weekly theme that still does not include you. How long before they will be allowed to acknowledge your divinity too?

I am encouraged by small changes, but change takes time. For now, I will speak your name. I will make you part of our eternal narrative. I will share your love and stop myself from looking past you. I will teach my children to see your light and be lifted by your strength, that they will speak your name as easily as they do Father’s—for both of you are part of their eternal makings.

All my love,

Daughter

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[post_title] => Dear Heavenly Mother [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 55.1 (Spring 2022): 167I am encouraged by small changes, but change takes time. For now, I will speak your name. I will make you part of our eternal narrative. I will share your love and stop myself from looking past you. I will teach my children to see your light and be lifted by your strength, that they will speak your name as easily as they do Father’s—for both of you are part of their eternal makings. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => dear-heavenly-mother [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-09-23 01:12:22 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-09-23 01:12:22 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=29142 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

“O My Mother”: Mormon Fundamentalist Mothers in Heaven and Women’s Authority

Cristina Rosetti

Dialogue 55.1 (Spring 2022): 119–135

As the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints moved away from the plural marriage revelation, a marital system that created the cosmological backdrop for the doctrine of Heavenly Mothers, the status of the divine feminine became increasingly distant from the lived experience of LDS women. Ecclesiastical changes altered women’s place within the cosmos.

The doctrine of Heavenly Mother has long been invoked by Mormon women and Mormon feminists to posit an expanded view of gender in Mormon cosmology and offer women a tangible representation of their eternal future. At the same time, the lack of worship or veneration of a divine feminine in Mormonism raises the question of whether the doctrine has the potential to influence the temporal state of Mormon women. Historically missing from the literature and theological critiques is the inclusion of Mormon groups where this is already happening. Mormon communities outside of the LDS Church have given Heavenly Mother a place in their meetinghouses, a priesthood role in temple liturgy, and considered the tangible outcomes of her cosmological significance in late-night conversations around the dinner table once the children are asleep and the dishes are clean. This article explores the theology of Heavenly Mother in Mormon fundamentalisms and the way it influences access to religious authority.

In 2018, I sat in a meeting of the Apostolic United Brethren (AUB) at the Rulon C. Allred building in Bluffdale, Utah and opened the hymnbook to Hymn no. 3, “O My Father.”[1] As I prepared to sing the hymn that became both a foundational theological text and a staple in LDS meetinghouses across the nation, I looked to the previous page and saw Hymn no. 4, “O My Mother.” The hymn, attributed to Eliza R. Snow, moves beyond LDS speculation of a Heavenly Mother and offers women an avenue for seeing themselves in Mormon cosmology.[2] Their exaltation is not invisible, it is tangible and reflected in the voices of women who sing the hymn at their Sunday afternoon meetings.

O my Mother, my heart longest

To again be by Thy side,

In the Home I once called heaven

In Thy Mansion up on high.

How you gave me words of counsel

Guides to aid my straying feet.

How you taught me by true example

All of Father’s laws to keep.

This hymn is not the only place where Heavenly Mother is invoked in the fundamentalist movement. Since their earliest publications, fundamentalists spoke highly of Heavenly Mother, even hypothesizing a “Trinity of Mothers” and referencing the “Goddess of this world.”[3] For many fundamentalists, Heavenly Mother is not absent; they know they have “Mothers there,” as Snow wrote with assurance. As a perceived continuation of early Mormonism, the fundamentalist movement relied on the work of nineteenth-century thinkers such as Eliza R. Snow and Edward W. Tullidge to posit a Heavenly Mother with divine authority as an integral part of Mormon cosmology.

At the same time, the doctrine that potentially affords women eternal representation is complicated by its entanglement with plural marriage, something both LDS and non-LDS feminist theologians have long deemed oppressive. The possibility of increased access to religious authority does not overshadow the numerous traumatic experiences of women within fundamentalism nor the documented abuse in these communities. Mormon groups that developed from Alma Dayer LeBaron’s ordination claim, referenced throughout this article, are fraught with cases of incest and underage marriage. The accounts of women’s access to a divine feminine stand alongside abusive experiences. An acknowledgment of Heavenly Mother and women’s priesthood in Mormon fundamentalism does not negate or diminish the harm caused to many women and children of the tradition.

Mother(s) There

Three decades after the publication of “O My Father,” Eliza R. Snow published another poem with additional insight into the divine feminine and the earth’s Heavenly Mother. In her 1877, “The Ultimatum of Human Life,” Snow penned:

Obedience will the same bright garland weave,

As it has done for your great Mother, Eve,

For all her daughters on the earth, who will

All my requirements sacredly fulfill.

And what to Eve, though in her mortal life,

She’d been the first, the tenth, or fiftieth wife?

What did she care, when in her lowest state,

Whether by fools, consider’d small, or great?

’Twas all the same with her—she prov’d her worth—

She’s now the Goddess and the Queen of Earth.[4]

For Snow, a plural wife, the doctrine of Heavenly Mother was part and parcel of Smith’s cosmology that fashioned a “material heaven, comprising eternal sealed relationships between believers, both male and female.”[5] The doctrine of exaltation was dependent on an intricate connection between the entire human family, of which women were a significant part.

While there are no firsthand sources from Smith that directly reference women’s exaltation or Heavenly Mother, historian Jonathan Stapley notes that the assumption of women’s participation was prevalent to the women who were among Smith’s close associates.[6] As part of the construction of the Mormon heaven, Smith initiated complex sealings that sought to bind the entirety of humanity. Through temple sealings, Smith constructed a way to “[bridge] the gap that divided Mormons from each other in the cosmological priesthood network.”[7] Part of this sealing network were the institutions of both adoption and polygamy. By the time Snow penned “O My Father,” she was aware of the polygamous sealings that were part of the kinship bonds of heaven. Three years prior, on June 29, 1842, Snow married Smith as a plural wife. As such, her beloved hymn included the assumption of plural marriage. When she wrote her assurance of a Mother in Heaven, which she testified as evident based on both reasonable and eternal truth, she likely assumed there was more than one.[8]

Women’s exaltation, like men’s exaltation, is tied to the bonds forged over temple altars: their marriages and children. For this reason, Mormon cosmology is based on a required gender reciprocity. Men and women are, as scholar Amy Hoyt has written, “interdependent and must rely on each other for exaltation, although they may be individually saved.”[9] This is echoed by theologian Blaire Ostler, who emphatically argued, “His godhood is dependent on Her, just as Hers is dependent on Him.”[10] However, the emphasis on a single exalting union is a recent development. Celestial marriage only became synonymous with eternal marriage, rather than plural marriage, in the late nineteenth century.[11] Prior to this time, Mormons believed in a theological framework where the exaltation and deification of women was inseparable from plural unions.[12]

Like the rituals necessary for exaltation, the power behind the sealing ritual required a gender reciprocity in the early years of the Church. During the period that Smith revealed the sealing ritual, he further elaborated on the doctrine of priesthood through the temple liturgy. In his work on the early evolution of Mormon priesthood, Jonathan Stapley differentiates between the ecclesiastical priesthood, marked by offices and ordination, and the temple or cosmological priesthood, which was a means of “materializing heaven” and forging eternal bonds.[13] The cosmological priesthood was the force that cemented earthly relationships and solidified the human family through a complicated web of dynastic sealing. For the cosmological priesthood to function, women’s participation was not only welcome but vital.[14] Because it was familial in nature, the priesthood in the temple required women’s participation.

In the nineteenth-century Mormon context, the temple liturgy that instructed the initiated in the sacred knowledge of exaltation was intimately tied to polygamy and reserved for participants in the Anointed Quorum.[15] The families forged on altars “had become the lingua franca of an exaltation that was steeply gendered and rooted in polygamy. In this version of plural theology, women are not denied exaltation, by any means,” writes scholar Peter Coviello.[16] Further, “As mothers of children, they become gods in their own right. . . . They may become gods—Mothers in Heaven—but they are gods who obey. They emerge, we might say, as gods in subjection.”[17] Like Mormon men, who understood themselves as “gods in embryo,” women similarly foresaw their future exalted state as one of deity.[18] Within this framework, women’s deification was specifically connected to their status as wives and mothers. This was further promoted by Brigham Young, who centered both plurality of wives and women’s reproduction in his discussions of exaltation.[19]

The connection between plural marriage and exaltation was difficult to untangle as the Church moved away from the practice. This was only further complicated by the continuation of plural temple sealings for divorced Latter-day Saint men and widowers, as well as the continued canonical status of the plural marriage revelation. Given the connection between plural marriage and women’s deification, some LDS women authors focus their attention on “the consequences of a female deity for women,” one being eternal polygamy.[20] It is this underlying assumption in Snow’s poetry that informed many early views of women’s eternal nature as well as the current fundamentalist theology of exaltation. At the same time, while embraced by polygamists across the Restoration, it is the assumed polygamous heaven of the nineteenth century that lends to concern among Latter-day Saint women who fear an eternal state unlike the monogamous one they know on earth. Carol Lynn Pearson’s The Ghost of Eternal Polygamy: Haunting the Hearts and Heaven of Mormon Women and Men documented this sentiment through research among LDS women who remain concerned about the potential for plural marriages.[21] In addition to hesitancy about their own eternal state, some Mormon women claim that the LDS Church’s silence on Heavenly Mother is connected to the anxiety-riddled question: Is there more than one?[22]

For members of the Mormon fundamentalist movement, this question was never unanswered. Those who attained exaltation were destined to eternal polygamous unions, just as their Heavenly Mothers. While the institutional LDS Church stagnated on doctrinal teaching around Heavenly Mother, the Mormon fundamentalist movement continued to offer insight into the nature of Heavenly Mothers. Drawing on nineteenth-century Mormon doctrine, Lorin C. Woolley’s School of the Prophets began teaching about Heavenly Mother in 1932 at a meeting of the members of his Priesthood Council. On March 6, Woolley offered names for the wives of Adam, whom he understood as the Heavenly Father of this world:[23]

Adam probably had three wives on earth before Mary, Mother of Jesus.

Eve—meaning 1st

Phoebe " 2nd

Sarah "

3rd, probably mother of Seth. Joseph of Armenia [Arimathea], proxy husband of Mary had one wife before Mary and four additional after.[24]

Woolley’s comment came with little context or extrapolation. However, his prophetic counsel initiated a tradition of naming the women who were deified as Mormonism’s Heavenly Mothers. Reference to the first people, Adam and Eve, as well as Phoebe and Sarah, gave early leaders an opportunity to explain the path toward women’s theosis, the ability for human beings to become gods, and the place of gendered faith in the process.

Six years after Woolley’s first reference to the divine feminine, Joseph W. Musser expanded the doctrine and gave increased import to the women of the Creation narrative. In his 1938 Mother’s Day editorial, he again drew on Eliza R. Snow and the “great and glorious truths pertaining to women’s true position in the creations of the Gods” found in her poems.[25] He wrote, “A Goddess came down from her mansions of glory to bring the spirits of her children down after her, in their myriads of branches and their hundreds of generations!”[26] “The celestial Masonry of Womanhood! The other half of the grand patriarchal economy of heavens and earth!,” he declared of the elevated state his cosmology supposedly afforded women in plural unions.[27] Women were not only eternal spouses, they were part of the cosmological structure powered by priesthood authority.

In addition to the literal exalted state of women, Musser spoke of the metaphorical feminine that permeates Mormon theology and existed prior to Adam and Eve’s descent to a telestial state.[28] According to his theology, the order of the cosmos was not only formed through patriarchal priesthood, but the birthing of the cosmological order necessitated womanhood and matriarchal power. Referring to Edward W. Tullidge’s nineteenth-century speculation on the nature of God, he asserted that before the temporal existence of our earth’s god, womanhood was manifest in the eternal structure of the “Trinity of Mothers—Eve the Mother of the world; Sarah the Mother of the covenant; Zion the Mother of celestial sons and daughters—the Mother of the new creation of Messiah’s reign, which shall give to earth the crown of her glory and the cup of joy after all her ages of travail.”[29] This trinitarian image of divine womanhood spoke to the theological place of the feminine not only embodied in women but inherent to the eternal worlds of Mormon cosmology, even before the creation of their temporal counterparts.

Becoming Queens and Priestesses

Women’s representation in the fundamentalist cosmos has the potential to afford women an avenue toward temporal authority. The exalted familial bond that exists as God in Mormonism allows for an interpretation of God’s power, or priesthood, as embodied in both men and women. Heavenly Mother not only represents women’s eternal future but the necessity of women’s priesthood to elevate her to godliness. As with their LDS sisters, motherhood is elevated and often equated with priesthood. Blaire Ostler notes the conundrum this presents: “Motherhood is of such importance for Latter-day Saint women that it is often compared to a man’s priesthood ordination—not in his participation in parenthood as a father, but in his divine right to act in the name of God through priesthood authority.”[30] Within the LDS Church, where priesthood is not offered to women at this time, women’s authority remains located in the reproductive sphere. Unlike with LDS women, early differentiations between an ecclesiastical and cosmological priesthood allows some fundamentalist women a recognized authority in some religious spaces. This is most often attained through the Second Anointing, but also in independent ordinations to various offices. With this in mind, one of the overarching questions is the extent to which cosmological parity translates into the elevated temporal status of women, a question long raised by the Mormon feminist movement.

In the nineteenth century, women who practiced polygamy diminished their marital desires in the present life for a reward in the next life. Women could be gods, but only in relation to men. “The revelation on plural marriage promised women greater celestial glory in exchange for consenting to the practice, and anecdotal evidence agrees that at least some (and perhaps most) of the women were motivated by otherworldly promises for them and their families,” notes historian Danny L. Jorgensen on the conundrum of Mormon deity.[31] Despite the authority afforded to women who elevated their social position through marriage and family life, it remained the case that women’s divinity was centrally located in the polygamous family. Peter Coviello has written that “the Heavenly Mother discourse, though valuable inasmuch as it counteracts the marginlessness of the identification between authority and masculinity, does very little to unwrite the confining of femininity, and especially feminine divinity, to the sphere of reproduction.”[32]

While women did not hold priesthood offices and were not ordained in early Mormonism, they were a vital component to the manifestation of God’s power on earth. The power that forged the cosmos was shared and manifest in the temple liturgy. This included being raised to the status of queen and priestess in the “fulness of the priesthood.”[33] Lucy Kmitzsch found her place within the fundamentalist movement shortly after her excommunication from the LDS Church in 1934. She and her sisters all married prominent members of the community, including Joseph Musser, Lorin C. Woolley, and J. Leslie Broadbent. In reminiscences of Lucy Kmitzsch’s life by her husband, she is referred to one of the best women in Zion and at performing ordinances.[34] The 1940 ordinance referenced by Musser resembled his diary entry for November 30, 1899, when he received his Second Anointing in the Logan Temple with his first wife.[35] For that reason, some assume that he both passed his priesthood authority to those outside the institutional Church and offered women the authority that stems from this ordinance. While this ordinance is no longer readily available to men and women in the LDS Church, this ceremony remains the avenue that many Mormon fundamentalist women are made sure of their exaltation and sealed into eternity as queens and priestesses.

In 2017, I witnessed the potential for cosmological motherhood to translate into priesthood at the semi-annual Solemn Assembly of the Righteous Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. During a women’s meeting, the general Relief Society president, a convert to the group from the LDS Church, stood to share a talk on the perseverance of the Saints and the place of women as central to building the faith in Zion. After her talk, I spoke with a member of the Apostleship about her comments. To my admiration of her eloquence and contribution, he simply replied, “Of course it was powerful. She has priesthood.” Like Kmitzsch, the continuation for the Second Anointing afforded the Relief Society president an authoritative position within her religious community, much like her own eternal Mothers. Within this ritual, women symbolically perform the biblical event when Mary anointed and blessed Jesus through a foot washing in preparation for his death and exaltation. Like Mary, interpreted as a wife of Jesus, Mormon women who participate in this ceremony prepare their husbands for exaltation and thus ensure their own eternal status.

Save for a couple of exceptions, fundamentalist groups do not offer priesthood ordination to women independent of the Second Anointing, an ordinance connected to marriage. However, for those that do, women share in the priesthood of their eternal Mother in their temporal lives. Some of the earliest examples of this occurred under the hand of Ross Wesley LeBaron, one of three successors to Alma Dayer LeBaron’s priesthood claim from Benjamin F. Johnson. During LeBaron ordinations to the patriarchal priesthood, women were ordained alongside their husbands in a joint ordinance symbolizing the gendered nature of the cosmos and the eternal state of all exalted people. In one ordination record, two serve as representative examples:

“William Edward Aldrich summer 1982 (and then his wife, Gloria, was ordained as Matriarch)

Thomas Arthur Green 19 Feb 1985 (and then Tom ordained his wife, Beth, as Matriarch).”[36]

One of the men ordained by LeBaron in November 1978, Fred C. Collier, continued this tradition among the women in his own Mormon community, even affording women “all the keys of the priesthood.”[37] For Collier’s group, this takes the form of full ordination to the priesthood. Jacob Vidrine, a historian of LeBaron priesthood, explains, “Fred teaches that women can perform all ordinances for other women, but says that sacrificial ordinances/the sacrament are male priesthood responsibilities properly performed by men, but that ordained women did have authority to perform them also.”[38] The authority to perform ordinances extends to women’s authority to baptize, confirm, bless, and ordain others to priesthood offices.[39]

In a 2014 photograph of one such ordination, a young woman wearing a black blouse sits in a folding chair in a living room. She is surrounded by five women with their right hands placed on her head and their left hands on the right shoulder of the woman beside them. The women receiving the ordinance was ordained to the office of elderess on that day, by ordained high priestesses. This image speaks to the broader tradition within the group. A 1992 ordination record exemplifies the practice. In the minutes of the proceedings, the officiant laid his hands on the woman’s head and declared:

[name redacted], through the authority of the High Priesthood of the Holy Order of God, we lay our hands upon your head and ordain you to the office of High Priestess and confer upon you all those keys and all those rights and privileges of this office. We ordain you and we confer upon you the High Priestesshood after the Holy Order of God. We do this in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.[40]

The record for this ordination reflects two women ordained to the office of high priesthesshood, the same office assumed by the exalted women in their cosmology. Within the context of this branch of Mormonism, “all the keys” included the power to seal families for eternity. In addition, there is one case of a woman ordained to the office of presiding matriarch.

In their own literature, fundamentalist Mormons explain the priesthood of women extending back to the early days of the Restoration and the role of their eternal Mother, Eve. Along the same theological lines of Adam’s exaltation as an example to all men, it is Eve’s position that became embodied by all women, including Emma Smith, the wife of the first Mormon prophet: “It was the Prophet’s mission to establish the Kingdom of God on Earth—it was a family kingdom. Its powers were vested in the King and Queen, the anointed husband and wife. In this order the parents literally stand as God and Goddess to their own family kingdom. The Prophet Joseph had chosen for his Queen the elect lady Emma—just as Joseph stood as Adam, Emma stood as Eve. She was the first woman received into the Holy Order and the first woman to be ordained to the fullness of the Melchizedek Priesthood.”[41]

As a religious tradition that argues for its place as an authentic expression of nineteenth-century Mormonism, the continued ordination of women is not seen as a deviation from Restoration history but a continuation. For this Mormon group in particular, women’s ordination does not come with limitation. On the contrary, their writing on the restoration of matriarchal priesthood argues that “had Emma been worthy to receive it, she would have presided over the kingdom as presiding Matriarch, High Priestess, Queen, Goddess and Eve. Even Brigham Young would have been subject to her—she would have been his Mother, Queen and Goddess!”[42] It is precisely because of Heavenly Mother that Mormon women across the Restoration can see themselves as active participants in the cosmological priesthood with their male priesthood counterparts. Whether this will translate into ecclesiastical priesthood in the future remains to be seen.[43]

Conclusion

Speculation on the place of Heavenly Mother began soon after the introduction of the temple liturgy. Eliza R. Snow took Joseph Smith’s teachings on embodied gods and exaltation and traced them to their logical conclusion, a Mother in Heaven. Since Snow penned her famous poetry on gendered deity, the doctrine of Heavenly Mother has expanded among Mormon women as a way to make sense of their eternity. At the same time, Mormon feminists have looked to the history of priesthood and Heavenly Mother as entry points to understand women’s authority in the Church. However, the authority of women in the temple and the theology of Heavenly Mother was historically tied to relationship. Women could exercise priesthood and become gods, but only within the bonds of marriage, specifically polygamous marriage.

As the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints moved away from the plural marriage revelation, a marital system that created the cosmological backdrop for the doctrine of Heavenly Mothers, the status of the divine feminine became increasingly distant from the lived experience of LDS women. Ecclesiastical changes altered women’s place within the cosmos. However, for women involved in the fundamentalist movement, where the ambiguity over eternal polygamy is absent, the doctrinal continuity afforded women more space to institutionally discuss the place of women in the afterlife. The cosmological priesthood associated with their theological view of Heavenly Mother remains an avenue for women’s authority.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Eliza R. Snow, “My Father in Heaven,” Times and Seasons 6, Nov. 1845, 1039. For a discussion of this poem and hymn, see Jill Mulvay Derr, “The Significance of ‘O My Father’ in the Personal Journey of Eliza R. Snow,” BYU Studies 36, no. 1 (1996–97): 84–126.

[2] The hymn was written by William C. Harrison and originally published as “Companion Poem to Eliza R. Snow’s ‘Invocation’” in the March 1, 1892 issue of the Juvenile Instructor, edited by George Q. Cannon.

[3] Joseph W. Musser, “Comments on Conference Topics,” Truth, May 1938.

[4] Eliza R. Snow, “The Ultimatum of Human Life,” in Poems, Religious, Historical and Political (Salt Lake City: The Latter-day Saints Printing and Publishing Establishment, 1877), 8–9.

[5] Jonathan A. Stapley, The Power of Godliness: Mormon Liturgy and Cosmology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 11.

[6] Jonathan A. Stapley, “Brigham Young’s Garden Cosmology,” Journal of Mormon History 47, no. 1 (Jan. 2021): 68–86.

[7] Stapley, Power of Godliness, 20.

[8] “O My Father,” Hymns, no. 292.

[9] Amy Hoyt, “Beyond the Victim/Empowerment Paradigm: The Gendered Cosmology of Mormon Women,” Feminist Theology 16, no. 1 (2007): 97.

[10] Blaire Ostler, “Heavenly Mother: The Mother of All Women,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 51, no. 4 (Winter 2018): 181.

[11] James E. Talmage, “The Story of Mormonism,” Improvement Era 4, no. 12 (Oct. 1901): 909. For an overview of the shifting view of celestial marriage in Mormon history, see Stephen C. Taysom, “A Uniform and Common Recollection: Joseph Smith’s Legacy, Polygamy, and the Creation of Mormon Public Memory, 1852–2002,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 35, no. 3 (Fall 2002): 113–44.

[12] For notable examples of Heavenly Mother described as a monogamous wife of God in Church history, see David L. Paulsen and Martin Pulido, “‘A Mother There’: A Survey of Historical Teachings about Mother in Heaven,” BYU Studies 50, no. 1 (2011): 70–97.

[13] Stapley, Power of Godliness, 11.

[14] Stapley, Power of Godliness, 26.

[15] See David John Buerger, “The Development of the Mormon Temple Endowment Ceremony,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 20, no. 4 (Winter 1987): 33–76.

[16] Peter Coviello, Make Yourselves Gods: Mormons and the Unfinished Business of American Secularism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 126.

[17] Coviello, Make Yourselves Gods, 126.

[18] Coviello, Make Yourselves Gods, 55.

[19] Stapley, “Brigham Young’s Garden Cosmology,” 84.

[20] Danny L. Jorgensen, “The Mormon Gender-Inclusive Image of God,” Journal of Mormon History 27, no. 1 (Spring 2001): 100.

[21] See Carol Lynn Pearson, The Ghost of Eternal Polygamy: Haunting the Hearts and Heaven of Mormon Women and Men (Walnut Creek, Calif.: Pivot Point Books, 2016).

[22] Pearson.

[23] Brigham Young, Apr. 9, 1852, Journal of Discourses, 1:46.

[24] Joseph W. Musser, Book of Remembrances, transcribed and edited by Bryan Buchanan, 7. As described in the Book of Remembrances, Woolley further speculated that the wives of Jesus were “Martha (Industry), Mary (of god), Phoebe, Sarah (Sacrifice), Rebecca (given of God), Josephine (Daughter of Joseph), Mary Magdalen, and Mary, Martha’s sister.”

[25] Musser, Book of Remembrances.

[26] Joseph W. Musser, “Mother’s Day,” Truth, May 1938.

[27] Musser, “Mother’s Day.”

[28] Musser, “Mother’s Day.”

[29] Musser, “Mother’s Day.” See Edward W. Tullidge, The Women of Mormondom (New York, 1877).

[30] Ostler, “Heavenly Mother,” 175.

[31] Jorgensen, “Mormon Gender-Inclusive Image of God,” 118–19.

[32] Coviello, Make Yourselves Gods, 269n57.

[33] Coviello, Make Yourselves Gods, 17.

[34] “Journal, July 28, 1940,” Joseph White Musser Journals, 1929–1944, file no. 17. Photocopy in author’s possession.

[35] “Journal, May 1904,” Joseph White Musser Journals, 1895–1911, MS 1862, Journal 2, p. 104, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City.

[36] “Men who have been ordained by Ross W. LeBaron,” 1958–1995. Copy in author’s possession.

[37] “Ordinations and Confirmations at Hanna,” Apr. 3, 1992. Copy in author’s possession.

[38] Jacob Vidrine, interview by Cristina Rosetti, June 25, 2021.

[39] Even in groups where priesthood ordination is not conferred upon women, blessings remain a central part of fundamentalist women’s experience. This is especially true of Confinement Blessings before birth.

[40] “1992 Collier Ordination Record.” Copy in author’s possession.

[41] William B. Harwell, “The Matriarchal Priestesshood and Emma’s Right to Succession As Presiding High Priestess and Queen,” in Doctrine of the Priesthood 8, no. 3 (Mar. 1991): 12–13.

[42]. Harwell, “Matriarchal Priestesshood,” 13.

[43] There are currently no women leading Mormon groups. The only woman to lead a Latter-day Saint denomination, Church of Christ, was Pauline Hancock, who broke from Community of Christ. See Jason R. Smith, “Pauline Hancock and Her ‘Basement Church,’” John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 26 (2006): 185–93.

[post_title] => “O My Mother”: Mormon Fundamentalist Mothers in Heaven and Women’s Authority [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 55.1 (Spring 2022): 119–135As the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints moved away from the plural marriage revelation, a marital system that created the cosmological backdrop for the doctrine of Heavenly Mothers, the status of the divine feminine became increasingly distant from the lived experience of LDS women. Ecclesiastical changes altered women’s place within the cosmos. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => o-my-mother-mormon-fundamentalist-mothers-in-heaven-and-womens-authority [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-09-23 01:16:16 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-09-23 01:16:16 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=29137 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Guides to Heavenly Mother: An Interview with McArthur Krishna and Bethany Brady Spalding

Dialogue 55.1 (Spring 2022): 135-166

When Dialogue asked us to write a personal article about our process of writing A Girl’s Guide to Heavenly Mother (D Street Press, 2020), we were delighted.

When Dialogue asked us to write a personal article about our process of writing A Girl’s Guide to Heavenly Mother (D Street Press, 2020), we were delighted. The work Dialogue does is so important that it was quite a compliment to be included. For this contribution, we decided we would take the opportunity to interview ourselves. We have done lots of podcasts and interviews, but sometimes as an interviewee you just don’t get to say everything you wished you would have, or you don’t get asked questions you want to answer. So, below is our very own self-guided Q&A, for your reading pleasure.

Q: Why did you start writing children’s books?

Bethany: We’re fond of this quip from a wise fictional gas-station attendant aptly named Socrates: “The secret of change is to focus all of your energy not on fighting the old, but on building the new.”[1] McArthur and I get all fired up about so many good things in the gospel, but we are also pretty feisty about wanting change in the Church—first and foremost a wider embrace of Heavenly Mother and a greater recognition of the power and divinity of women (so that we can live up to our theology of the divine partnership of Heavenly Parents). So we had to decide: we could rant and rave about the lack of strong, spiritual women in our church curriculum and conversations, or we could get busy and create stories to help fill that void. And with the inspiration to invest in the rising generation, we knew that children’s books were the best place to start. So we set out writing in hopes of illuminating and building the next generation of Latter-day Saints to have a fuller sense of feminine divinity.

McArthur: Plus, Bethany and I both have three daughters. We want the world to be a different place for them to grow up in. Look around. Is this a world whose policies, culture, governments, and relationships honor women? (Hint: no.) Meg Conley has recently written about how the pandemic made the lack of respect and support for women’s domestic work abundantly clear.[2] Gabrielle Blair’s essay on birth control elucidates the gender bigotry enmeshed in the system.[3] Statistics on how much women are paid (or not paid) make the gender pay gap clear. And, frankly, these are just the systems within my own country. Around the world, women face discrimination and are given second-class status. If we want to sway the world, then we need to teach children correct principles.

Q: Wait! You had an agenda when writing these books?

McArthur: Um, why, yes. An agenda simply means to have an intent or a goal, an “underlying ideological plan.”[4] Our plan is that we need our children’s books to reflect our doctrine. And, trust us, writing children’s books is not lucrative or glamorous enough to spend years of your life doing it for simple kicks. In fact, every year we consider retiring. And then we look at each other and ask, “Is there anything more the world needs from us?”

Now, sometimes people appreciate our agenda and sometimes they don’t. That’s fine. It actually doesn’t matter. Not everyone needs to buy every book. (Though, if they did, then at least the lucrative angle would change.) What matters is that 1) we feel we are using our talents for good in the world and 2) we get enough feedback from others who feel their life has been positively impacted for us to think our efforts were worth it.

Soooo, so far, we have always felt there was one more . . .

Q: Why did you choose each other as creative partners?

Bethany: If you were to meet McArthur, you’d quickly want to come up with a reason to dive into a project with her. She’s a helluva storyteller, wicked smart, and doesn’t take no for an answer (I’ve nicknamed her the Holy Harasser). Plus, she co-owned a communications company and knows how to get shizam done! McArthur and I had been neighbors in Washington DC, where we both served with the youth in urban wards and came to know how vital role models are. And she just happened to be visiting me in Mumbai, India when my almost-three-year-old daughter, Simone, asked the earnest question “Where are all of the stories of the girls?” after I finished reading her a children’s scripture book. So a dose of friendship and fate turned McArthur into my coauthor.

McArthur: Well, I was lucky Bethany called me up. And, after six books, I have to say I couldn’t ask for a better partner. I like working with people who are forces of nature—I want to grab onto their tornado whirlwind and go for the wild ride of their vision. And, P.S., it helps if they also happen to have mad editing skills to balance the deluge I drop onto a page.

Q: Why did you decide to write books about Heavenly Mother?

Bethany: From the get-go, I wanted to write about Heavenly Mother. Our Girls Who Choose God series was a great warm-up, getting readers comfortable with matriarchs and prophetesses and women judges and generals. The women from the scriptures and Church history were dynamo, but they were still human. Why not introduce girls to their ultimate female role model, Heavenly Mother? I have a master’s degree in public health and have worked on food security and nutrition programs in many communities in the US and around the world. But in my early thirties, I started to feel spiritually malnourished. Everything I worshiped and revered and thought of as sacred was male. Surely, this wasn’t a balanced diet that would promote my well-being. And as I became a mother and started having daughters, I felt compelled to come up with new meals, new recipes to nourish my girls’ spiritual development. I couldn’t just feed them the patriarchy I had grown up on. We needed to whip up a big serving of Heavenly Mother to have a more balanced spiritual feast. My own soul, my girls, and the whole world felt like it was starving for Her.

McArthur: When I was twelve years old, someone explained to me how a traditional marriage and family worked. And I thought, “Why would I possibly sign up for that? To be an inherently, divinely appointed second-class human? And why would I believe in Heavenly Parents who think that?”

Turns out—They don’t.

Traditional, for the record, is a terrible term. There is no inherent worth in something existing simply because it already does. Traditions can be beautiful and empowering, and traditions can be false and demeaning. Traditional marriages have included all those aspects. On the negative side, a “traditional” family has included such things as children not speaking until they are spoken to, women manipulating men (as was thoroughly detailed in Helen Andelin’s Fascinating Womanhood and often taught in Relief Society), corporal punishment, unrighteous dominion, unequal partnership, and more.[5]

Bethany’s husband started using a different phrase: a divine marriage. And that’s a fabulous term. A divine marriage and family are based on mutual love and support, an understanding that everyone’s growth and development are worth investing in, and righteous partnership, which is modeled by our Heavenly Parents.

The divine model for marriage should be based on what we know of our Heavenly Parents’ relationship. Your first thought might be, “But what do we really know?” Turns out, after we did all the research for these books, plenty.

And once we saw that there was a lot of information to construct a new divine model, we knew it had to be told. Young children—both girls and boys—needed to be shown this model as something to aspire to.

Q: Why does Heavenly Mother matter?

Bethany: We Mormons speak so much about the fullness of the gospel. But to me, it really feels like we’re wrestling with just half. The splendid poet Carol Lynn Pearson writes that we can’t have holiness without wholeness.[6] And to me, wholeness is only found as we embrace Heavenly Mother and welcome Her into our collective and personal worship and spiritual lives. To have a fullness of the gospel, we need both our Heavenly Parents. Can you imagine what would change if we disregarded the cultural baggage of a “heavenly hush” surrounding Her and instead shouted out a “heavenly hallelujah”? Imagine how young girls in Primary would feel if we included Heavenly Mother into the hymn: “I am a child of God / and They have sent me here.”[7] Imagine how teenage girls would think of their bodies if they fully knew that God has breasts and hips and curves. Imagine how newly endowed sister missionaries would serve if they saw Heavenly Mother as part of the creative process in the temple ceremony. Imagine how young professional women could work in the world knowing that Heavenly Mother is a creative powerhouse. Imagine a new bride beaming after a sealing ceremony performed by a woman and man, celebrating a union in the image of our Heavenly Parents. Imagine how new mothers would feel giving birth and nurturing children, knowing about a Heavenly Mother equal in might and glory! And the list goes on and on . . .

McArthur: But let’s be clear: the truth of Heavenly Mother doesn’t just benefit girls, it’s also vital for boys! The prophet Spencer W. Kimball spoke often about Heavenly Mother. My personal theory on this is that because he lost his earthly mother at a young age, he was craving a mother’s love, and Heavenly Mother could help fill that void.

Originally, Bethany and I were only going to write A Girl’s Guide. We have daughters. We write “girls’ stories.” But a woman reached out to us—a mother of five boys—and asked that we include boys. That wouldn’t work for A Girl’s Guide—there were very specific reasons that we needed to discuss this doctrine in a female context. Yet the long list of reasons she offered was compelling. Boys can be blessed by the perfect love of a divine Mother.

Boys need to understand that girls are their equal—in the classroom, at work, in family life, at church, in the world. Boys need Heavenly Mother to more fully grasp the divine role of women.

Both boys and girls need to learn that the equality of their Heavenly Parents is the divine model in order to avoid the pitfalls of a skewed world. A few seemingly disparate examples come to mind:

- A recent study from Brigham Young University highlighted the overwhelming inequity of how men and women communicate in group projects. If these students understood the divine model of women and men working together, would those communication patterns be different? I think so.

- A book I recently read about Mongol queens described how their accomplishments were literally cut out of the official records.[8] The scrolls were sliced to remove their names, their roles, their actions. The world has removed the glory of women; truth can restore it.

- Having lived almost a decade in India, it is readily apparent that even in the present-day world, the glory of women is not honored. India practices female infanticide and has one of the highest female suicide rates in the world. But let us not overlook the sexism in our own backyard, including unequal pay in the professional world and unequal workload at home.

Bethany: And knowledge of Heavenly Mother benefits not only individuals but also communities and even countries. Our Heavenly Parents exemplify the divine model of equal partnership. As Valerie Hudson and co-authors’ work shows, the benefits of treating women more equitably are stunning.[9] In countries with higher gender equality, people live longer, there is less disease, less war, and higher levels of education. The divine model is equality. When we as humans follow a divine model, better things happen everywhere.

McArthur: So why do we write these books? Why did we think it was worth highlighting these truths? To change ourselves, our families, and the world. You know. Just that.

Q: How did you choose the art for the guides?

Bethany: McArthur was the genius behind gathering the art for the book, so I’ll let her answer with all the details. But we both felt adamant that the art be expansive and widen our understanding of God, knowing that how we humans view God determines what we believe is sacred and supreme. If we believe only in a white, male God then of course whiteness and maleness become superior. And this has damaging effects. Living in Richmond, Virginia (the capital of the Confederacy) during the racial unrest and reckoning in the spring and summer of 2020, I saw up close the ugliness of white supremacy. We wanted our guides to be part of the solution to achieving racial justice.

McArthur: We were incredibly blessed to receive the contributions of more than fifty artists. Most of the pieces in the book were done specifically for the book, which is a great risk and investment on the artists’ side.

In my own immediate family, we have Polynesian, Haitian, Native American, East Indian, and a mix of European heritage. To show a Heavenly Mother as only white would be an appalling assertion. We wanted to ensure that as many people as possible who saw the book had an entrance point to relate to their own Heavenly Mother. So, in our book we have depictions of Heavenly Mother from artists in Cambodia, South Africa, Nigeria, Lebanon, Canada, Argentina, Qatar, and New Zealand. Heavenly Mother is depicted as Polynesian, African American, Native American. We have images that are very classical and images in the style of street art. In order to find such a wide range of talented artists, we were lucky to have the resources of the Church History Museum. Their international art competitions from the last fifteen years are available online, so we were able to cull many of our international artists from there.

Through this project, we’ve seen just how much art matters. When my husband (who is not of our faith) toured the Conference Center for the first time, he turned to the guide afterward and said, “Is your church a men’s club? Sure looks like it.” For the record, we had had zero conversations about gender and the Church—he was just observant. Later, when we published the Girls Who Choose God series, I thought it was an opportunity to change the face of the Conference Center. We heard that the Church leaders were aware of this quandary and were actively working to change it. We are happy to say that Kathleen Peterson’s powerful images of women from the scriptures were some of the first art depicting women to hang at the Conference Center. For two years, girls could go to general conference and see themselves in these inspiring portraits. Now, we are happy to say that the first image of Heavenly Mother to appear on Temple Square was Caitlin Connolly’s painting In Their Image, commissioned from the cover of our book, Our Heavenly Family, Our Earthly Families. Images can reflect truth; they can also obscure it. Let’s choose truth.

Q: Tell us about some of the art.

McArthur: Every time someone asks me about my favorite artwork in the series, I answer differently because they all make me swoon. But, today, one of them is particularly on my mind. Laura Erekson created a portrait of Heavenly Mother by embedding objects in plaster. It is magnificent. A God with Her arms outstretched wide and open. And, what I love the best, Her crown, Her glory, is made of tools. Pliers, specifically.

The phrase comes to mind that we are our Heavenly Parents’ “work and glory”—and what a powerful way to show that! And what a reassuring truth to understand—that in addition to a divine Brother’s and Father’s love, we also have a Mother’s love!

Bethany: Well, I am sitting here staring at Richard Lasisi Olagunju’s Nigerian rendition of our Heavenly Parents. We needed a safe home for it until our art show in Provo in May 2021, so I happily volunteered my bedroom wall. It is about four feet tall, completely hand-beaded. Every day it serves as a bold reminder to me and my husband to work through our conflicts, reconcile, and aspire to a loving and full partnership. Plus, I need to up my hairdo game.

Q: Is there any significance to the colors on the cover of the Girl’s Guide?

McArthur: Why, yes. Thank you for asking. With these books, we actually got to decide the cover. That is not how the children’s book world usually works. So, we decided that we wanted a color that carried all the celebration of life, vibrancy, and energy that we would imagine. What would represent that better than hot persimmon coral orange? (Plus, if you see Bethany’s kitchen stools or my chaise lounge, you’d see we both live with that color too! Hmm, I just realized that Bethany’s kitchen stools and my chaise each says quite a bit about our individual passions.)

Bethany: Additionally, one of the most beautiful descriptions of Heavenly Mother came from a rabbi. He had a vision of Heavenly Mother in Her glory: “he saw Her dressed in Her robe woven out of light, more magnificent than the setting sun, and Her joyful countenance was revealed.”[10] For us, this bold color was a tribute to the vividness of the setting sun.

Q: Why did you choose a guide format for the books?

McArthur: We wrestled with how to convey the abundance of information about Heavenly Mother in a way that was interactive and accessible for young people. Then, Bethany was inspired—a guidebook! Bethany and I are both travelers and have relished seeing the wide-reaching parts of our Heavenly Parents’ stunning planet, and guidebooks have been our fast friends along the way. Voilà! So, we sat down to see if that could work. And by sat down, I actually mean we Skyped, FaceTimed, WhatsApped—whatever technology could connect us from rural India to Richmond, Virginia, then Australia, Bhutan, South Africa, Greece, and more far-flung places as Bethany’s family worked their way around their global sabbatical. (You can see how some of these places now feature in the guidebook!)

Bethany: And the guidebook format enabled us to highlight three different sections for our readers: first, a focus on the divine attributes of Heavenly Mother; second, discovering how Heavenly Mother teaches us magnificent truths about ourselves; and third, a call to action: use these sublime truths to create a more loving world!

Q: Who should read our guides to Heavenly Mother?

Bethany and McArthur: So, if you are interested in making change, children are a good place to start. Children have not yet heard the false traditions of our forefathers or our cultural taboos around Heavenly Mother. We don’t want them to go through life as we did, lacking a key component of the identity of God and hence our own.

However, the truth of our Heavenly Mother is clearly not a doctrine that only benefits children. As Joseph Smith taught, we need to have a correct understanding of God in order to understand our own nature and destiny.[11] Hence, this is for everyone. Literally. We’ve been delighted to hear from little kids, great-grandmas, middle-aged bishops, Young Women presidents, elderly high councilors, and others in-between who have been deeply moved by our books.

Q: How has writing these books changed your life, especially your relationship with Heavenly Mother?

McArthur: I think what has changed my relationship with Heavenly Mother even more than writing the books has been the interactions we have had with people since they’ve been published. Writing the books helped clarify a lot of information about Heavenly Mother. These were things I had heard from prophets and apostles scattered in articles here and there, and then the guides made a gathering place for all of them. And, frankly, that’s lovely, but it’s not the be-all and end-all. What happened from there is that people started asking us about Heavenly Mother and telling us about their faith journey to learn of Her. Those conversations pushed me to a place to realize that while I had spent the time and work to learn of Her, I had not put the same effort into actually having a relationship with Her. It is a very different thing to learn something academically and to learn something personally. Both are valuable, but one without the other is not enough. And so, while I have a list of moments when I have felt Jesus’ love for me or direction from my Father in Heaven, I now have added to my faith list a single interaction with Heavenly Mother. It was very clear that it was a different Being than who I had interacted with before.

Now that I know, I cannot not testify of Her. When I hear simple gospel phrases that slide out of our mouths, I want Her included. When people say “Our Heavenly Father’s plan for us,” immediately there is a bell that goes off in my head. The truth is, almost all mothers I know are involved in or even the primary planners for the family, so I cannot imagine Heavenly Mother not being involved in the plan of salvation. We also have a quote by Elder M. Russell Ballard talking about our Heavenly Parents’ plan for us.[12] So, the most truthful portrayal of the plan of happiness is one that includes both of them.

This is true for many, many phrases we use. “I know my Heavenly Father loves me” is often said in sacrament meeting. Yes, good to know that. Do you also know you are beloved by your Heavenly Mother? Speak that truth. It matters.

Bethany: Amen!

McArthur: And a heavenly hallelujah!

Q: What response have the books received?

Bethany: The responses we have received have prompted some of the most humbling moments of our lives. We hear from grown women and men who say that this knowledge changed the trajectory they were on and tell us how much they wished they would have had it sooner.

We have written a handful of children’s books but never has one resonated as deeply as this. People buy one book, and then we see that a week later, they come back and buy a dozen more. It is clear that when they get it in their hands, they feel the power of the truth, and they want to share! We have been taught to let our light shine, and I think this relates directly to knowledge of Heavenly Mother. Simply, truth helps people. Why hide it?

I think this leads us into our last question . . .

Q: What are our hopes for the Heavenly Mother books?

Bethany: That people feel loved—divinely, gloriously, perfectly loved by both Heavenly Parents. And that that love spills out into the world to create a more balanced, beautiful place.

McArthur: That women will come to know their own worth and the worth of their sisters. That they will come to expect—and work for—the world to move closer to the divine model.

If you have questions you wished we would have answered, feel free to ping us via email (mcarthurkrishna [at] gmail.com and bethanybrady [at] yahoo.com) or social media (Instagram @mcarthurkrishna-creates).

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Dan Millman, Way of the Peaceful Warrior (Los Angeles: J. P. Tarcher, 1980; repr. CreateSpace, 2009), 175.

[2] Meg Conley, “America Doesn’t Care about Mothers,” Gen, Aug. 19, 2020.

[3] Gabrielle Blair, “Men Cause 100% of Unwanted Pregnancies,” Human Parts, Sept. 24, 2018.

[4] Merriam-Webster, s.v. “agenda (n.),” accessed Nov. 1, 2021.

[5] Helen B. Andelin, Fascinating Womanhood (Santa Barbara, Calif.: Pacific Press, 1963).

[6] “Finding Mother God — Carol Lynn Pearson,” interview by Aubrey Chaves, Faith Matters, Sept. 13, 2020.

[7] See “I Am a Child of God,” Hymns, no. 301.

[8] Jack Weatherford, The Secret History of the Mongol Queens: How the Daughters of Genghis Khan Rescued His Empire (New York: Crown, 2010).

[9] Valerie M. Hudson, Bonnie Ballif-Spanvill, Mary Caprioli, and Chad F. Emmett, Sex and World Peace (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

[10] Val Larsen, “Hidden in Plain View: Mother in Heaven in Scripture,” SquareTwo 8, no. 2 (Summer 2015).

[11] Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2007, 2011), 345.

[12] M. Russell Ballard, When Thou Art Converted: Continuing Our Search for Happiness (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2001), 62.

[post_title] => Guides to Heavenly Mother: An Interview with McArthur Krishna and Bethany Brady Spalding [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 55.1 (Spring 2022): 135-166When Dialogue asked us to write a personal article about our process of writing A Girl’s Guide to Heavenly Mother (D Street Press, 2020), we were delighted. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => guides-to-heavenly-mother-an-interview-with-mcarthur-krishna-and-bethany-brady-spalding [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-09-23 01:15:24 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-09-23 01:15:24 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=29138 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

In Defense of Heavenly Mother: Her Critical Importance for Mormon Culture and Theology

Margaret Toscano

Dialogue 55.1 (Spring 2022): 37

Marginalizing God the Mother does not solve the problems raised by Mormonism’s doctrine of divine and human embodiment. It merely diminishes femaleness as a reflection of divinity. We do not need fewer images to understand God; we need more. Critics of Heavenly Mother have not fully grasped the negative consequences of moving toward a God beyond gender

Introduction

Does the existence of the Heavenly Mother in Mormon theology promote heteronormativity that marginalizes gender nonconforming individuals? If so, why does the divine female, but not the divine male, bear the bulk of the blame for this marginalization? Why has her body and not his increasingly become the battleground over the nature and meaning of sex and gender for persons both human and divine in Latter-day Saint discourse and practice?

Though she has achieved acceptance in Mormon theology and culture, Mother in Heaven is still marginalized by the LDS Church. She is mostly absent in church worship and everyday orthodox practice and primarily referenced not as an individual deity but as one of the heavenly parents, a vague designation that subsumes her into a divine patriarchal family, serving as model for the 1995 “The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” published by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. As a result, her nature, dignity, and godhood remain vague in mainstream Mormon discourse because her status is uncertain, her role in creation and redemption is undefined, and because even her weakened standing in Mormon theology has been used by Evangelicals as an argument that Mormons are not fully Christian. In addition, many LDS women, orthodox and feminist alike, have long worried that Heavenly Mother is emblematic of nineteenth-century LDS apostle Orson Pratt’s version of a polygamist godhead consisting of a Heavenly Father joined to multiple heavenly mothers who are eternally pregnant and, like queen bees, forever reproducing offspring not in a matriarchal hive but in a patriarchal kingdom. In their 2020 article, “‘Mother in Heaven’: A Feminist Perspective,” which is a response to the LDS Gospel Topics essay on this subject, Caroline Kline and Rachel Hunt Steenblik point to hopeful, recent developments that work toward “dismantling cultural silence,” “legitimizing as authoritative church doctrine” positive statements about the divine female, and using capital letters and the singular in the printed term “Heavenly Mother.”[1] Nevertheless, the authors argue that the Church’s short essay does not go far enough to establish Heavenly Mother’s godhood or her nature and standing in LDS practice and theology.

Recently, scholars with progressive views have also questioned depictions and possibly the value of Mother in Heaven, arguing that she promotes heteronormative sexuality that privileges just one image of “woman.” In “Rethinking Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother,” Taylor G. Petrey criticizes certain Mormon scholars (namely, Janice Allred, Valerie Hudson Cassler, and me): “Mormon feminists writing about Heavenly Mother have been complicit in heteronormative narratives that universalize a subset of women as the hypostasis of ‘woman.’”[2] Petrey’s concern has become the center of LGBTQ gender critique in current LDS theological discussions where the Mother God, rather than her male counterpart, is seen as the culpable party. This new liberal critique accepts as normative the LDS Church’s simplistic view of Heavenly Mother as supportive wife of a presiding patriarchal Heavenly Father, as a female figure whose presence reinforces the structure of the conservative nuclear family that the LDS Church now projects into the eternities. Consequently, Mother in Heaven has become a stumbling block for many people.

In this essay, I will interrogate the views and arguments surrounding Heavenly Mother advocated in Mormon discourse on both the right and the left. I do not have space to answer and explore all the questions raised above. Instead, I will focus on the place where mainstream and liberal discourses converge, namely on Heavenly Mother’s role as the wife of the Father God and the mother of his children. I will challenge both current Church teachings as well as Petrey’s simplified summary of my past work. I have explored multiple nuanced images and figures that represent the female divine, such as a trinity of Mother, Daughter, and Holy Spirit who parallel the male godhead in form and function and who “have been intimately involved in our creation, redemption, and spiritual well-being” from the beginning.[3] In this essay, I will highlight Mary, Wisdom, and the Holy Ghost or Comforter as central manifestations of God the Mother who reveal her divine wisdom, justice, mercy, and love, not merely her subordinate role in the patriarchal family unit. Multiple presentations of the Mother God rooted in Mormon texts challenge the view that she merely reinforces one kind of essentialized woman or mother. On the contrary, her many roles present a polymorphous divinity who makes room for gender nonconforming people.