Reproduction and Abortion

Introduction

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saint holds a distinct perspective on reproduction and abortion, which is based on a combination of scripture, teachings from modern prophets, and a strong emphasis on the sanctity of human life. The history of abortion within LDS (Latter-day Saint) thought has evolved over time, reflecting changing societal norms, medical advancements, and shifts in Church leadership. The following articles reflect some of these shifts and thoughts.

Eve’s Choice

Erika Munson

Dialogue 56.3 (Fall 2023): 133–150

But Betsy was born. She was dangerously premature—especially so for those days. Everyone said that at birth she could have fit on a dinner plate (an image that haunted my young imagination). She wasn’t expected to survive. But she did. Perfect, whole, healthy.

Listen to an audio version of this piece here.

We understand the controversial nature of the problem. Millions of Americans believe that life begins at conception and consequently that an abortion is akin to causing the death of an innocent child; they recoil at the thought of a law that would permit it. Other millions fear that a law that forbids abortion would condemn many American women to lives that lack dignity, depriving them of equal liberty and leading those with least resources to undergo illegal abortions with the attendant risks of death and suffering.

From Justice Stephen Breyer’s majority opinion in Stenberg v. Carhart in 2000. The ruling struck down a Nebraska law that made performing a “partial-birth abortion” illegal.

When a subject is highly controversial—and any question about sex is that—one cannot hope to tell the truth. One can only show how one came to hold whatever opinion one does hold. One can only give one’s audience the chance of drawing their own conclusions as they observe the prejudices, the limitations, the idiosyncrasies of the speaker.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

All the cousins knew Aunt Marla’s story. Her doctors in Salt Lake City said it was unlikely she could survive a pregnancy. So she and Uncle Bill adopted two beautiful children. Then, several years later, Marla had an unplanned pregnancy. Her obstetrician refused to consider an abortion, even though keeping the baby to term might result in her preventable death and two motherless kids. Bed rest. Lots of worry. Plenty of anger directed at our very own LDS Church.

But Betsy was born. She was dangerously premature—especially so for those days. Everyone said that at birth she could have fit on a dinner plate (an image that haunted my young imagination). She wasn’t expected to survive. But she did. Perfect, whole, healthy.

This story isn’t going where you think it is. It would be understandable if Betsy herself had become an argument, an important family story, that challenged abortion. But somehow it never did. The grown-ups we kids looked up to—our parents and grandparents—were New Deal Democrats. Some had broken with the Church. Some, like my parents, were weaving their LDS faith with progressive politics in an unconventional way. We felt the gratitude they all had for the miracle that was Betsy, but we also sensed their sorrow and anger for the horrible trap Marla and Bill were in before their daughter’s birth. Hypocritical? It didn’t feel like that to us. Several years later, my family moved to the East Coast, where my father, a physician by training, had left his practice to become dean of admissions at Harvard College. On a car trip home from summer vacation, I remember my parents discussing the recent Roe v. Wade decision. As my mother drove, my father turned to us kids in the back of the station wagon (wriggling around as usual in those pre–seat belt days). Suddenly somber, he looked us in the eyes and his features sharpened. “An abortion is a very sad thing.” He paused, bracing himself. “But a child coming into this world unwanted is tragic.”

It is in this context that I grew up a faithful member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Despite being at odds with the Church’s mostly male leadership who considered abortion “one of the most revolting and sinful practices in this day,”[1] my parents found deep satisfaction and belonging in our faith community. They taught by example how to walk with my coreligionists, especially when I disagreed with them. They encouraged me to turn to my own spiritual experiences and the fundamentals of LDS doctrine when I had questions, when I felt alone in my interpretation of God’s will. Our religion has not historically been a very big tent, but a small and hardy band of politically progressive Latter-day Saints (who frequently quarrel with one another) continue to hold some space inside that tent like our hero Senator Harry Reid did. And now, as a powerful alliance of my fellow citizens, elected officials, and Supreme Court justices have begun returning us to the circumstances my aunt faced in the 1960s, I have been thinking about why I persist in the conviction, based upon my faith, that a woman’s right to control her reproductive destiny is a sacred thing.

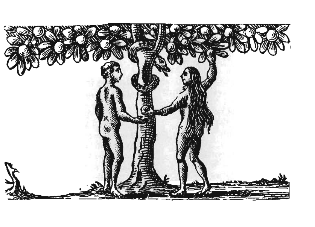

In LDS doctrine, Eve is the hero of the Eden story. The way we tell it, she and Adam were given conflicting commandments: multiply and replenish the earth, yet stay away from the tree of knowledge. They couldn’t do both. So Eve sacrificed the static peace of the garden for the messy growth that only mortality—including the bearing of children—could provide. Ironically, we believe that Satan’s attempt to corrupt humanity actually put us on a path toward salvation. We fell forward. Latter-day Saints give Eve full credit for making the right choice, even though this was God’s plan all along. The current president of the LDS Church, Russell M. Nelson (who, like his predecessors, teaches that most abortions are sinful), put it this way: “We and all mankind are forever blessed because of Eve’s great courage and wisdom. By partaking of the fruit first, she did what needed to be done. Adam was wise enough to do likewise.”[2]

The first reproductive choice I made was deeply informed by my spiritual life.

My adolescence was blessed by the example of women in our congregation who joyfully raised large families while skillfully attending to their personal growth. True to my comfort with juxtaposition, I married my boyfriend (he converted to Mormonism) while still an undergraduate at Harvard. Our friends just shook their heads. This was the eighties: no one was getting married. But Shipley and I were all in: living an off-campus Love Story plot without the tragic ending. Also unlike most others in my cohort, I wanted babies—lots of them—ASAP, even though I didn’t have a clue as to what my career goals were.

But motivated procreators though we were, my husband and I were realistic; we couldn’t afford a child right away. I’d get my BA, support him through graduate school, and then we’d start a family.

A few months into graduate school, my husband reported a vivid dream. He was sitting in an assembly of some kind in the upper room of the iconic LDS temple in Salt Lake City, the holiest of places where we make covenants with God and honor our ancestors. In the dream, everyone was dressed in white. It gradually dawned on my husband that the man sitting next to him was the president of our church at the time—our prophet, seer, and revelator Spencer W. Kimball. The old man turned to my husband, put his hand on his knee, and in his trademark gravelly voice said, “You know, I think it’s time you and Erika start a family.”

That was all it took. We stopped the birth control and figured the Lord would provide. What we didn’t know was that it would take us almost two years to get pregnant. Our first child arrived six months after my husband’s graduation, at which point we had a good salary and health insurance.

The irony that I was completely receptive to a man’s dream about a man’s instructions concerning what my man-God thought best is not lost on me. But more important to me than the gender of the messengers was the experience of God speaking to me about my unique situation, a basic tenet of Latter-day Saint doctrine. The good news that “the heavens were not closed” is an essential part of our religion’s origin story. Farm boy Joseph Smith took to heart a scripture from the Book of James and went to the woods to ask God a question about which church he should join.

If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him.[3]

When Joseph Smith walked out of those woods, he later reported a vision: God had a glorified body of flesh and bones. Like the heretical Christian mystics of centuries ago, Latter-day Saints embrace imago Dei, humans in the image of God, as an all-encompassing principle. Not only are our intellect and spirits divine, but we believe our bodies are as well and have the potential to be glorified in the hereafter. We go so far as to believe that ultimately, in the world beyond this one, we have the capacity to become gods. This doctrine, while understandably troubling to many Christian faiths, abides deeply in me. “As man now is, God once was: As God now is, man may be,” proclaimed church President Lorenzo Snow in the 1880s.[4] So what we learn from God about the bearing and raising of children in this life, we consider a prelude to becoming godlike creators in the hereafter.

Human agency, access to divine inspiration, and the holy responsibility of bringing children into this world: these are core LDS beliefs that, when it comes to abortion, result in my struggle with the institutional LDS Church.

On a balmy September evening in 2020, a text popped up from my neighbor Anne: I need to talk about abortion. She suggested a walk with me and our friend Katherine. My husband and I had just tuned in to the first US presidential debate of that election and the shouting had begun. I was happy to leave.

We three women are in the same congregation. I’m an old mom with adult kids and grandkids; Katherine has four school-age children. She leans left politically, and as we started talking, she expressed her frustration with pro-life stances that don’t include government support for low-income, single parents. Anne is younger, a doting mother to three-year-old Jacob. He was now thriving, but this little boy had spent six scary weeks in the hospital close to death with a respiratory condition. Anne and her husband dearly hoped for a second child but were unsure if that would ever happen. She was torn. She wanted to support women in the awful place of an unwanted pregnancy; her Christian principles informed her reluctance to shame or blame. But those same principles celebrated the magnificence of God’s creation—even his potential creation. It was very hard for her to feel okay about easy access to abortion. She was a careful consumer of social media but couldn’t ignore the horror stories she’d read online about late-term procedures.

As Katherine and I listened to Anne, we all felt gratitude for that moment. In contrast to the campaign vitriol that was being broadcast, streamed, memed, and tweeted in real time, we could show up in real life for each other. As the sky darkened and the stars emerged, I talked about my miscarriages: sad, early-week interludes during my childbearing years. I remember my private panic at a Christmas party when I discovered I was bleeding. Once home, I lay in bed with the quilt my mother had bought for her anticipated grandchild. When I closed my eyes, I saw a female spirit leave my presence and return to some cosmic waiting room—a cartoonish yet comforting vision. I was spared the deep sorrow that others endure; at that time, I had two little boys who were keeping our family humming. It took another year for my daughter to arrive, then our third son, then another miscarriage (this time on Thanksgiving), and at the end of a sixteen-year reproductive run, our second daughter, baby number five.

We stopped in the dark at a playground, and the lights blinked on. I remembered another story, one unique to my faith tradition. In the Book of Mormon (LDS scripture as opposed to the Broadway musical) there is a scene where Christ speaks to a prophet named Nephi on the American continent. Nephi has been praying for his people, who are under death threat for believing the prophecies of Jesus’ imminent birth on the other side of the world. Nephi is comforted when he hears the voice of the Lord saying, “be of good cheer . . . on the morrow come I into the world.”[5] Jesus the spirit speaks to Nephi, while Jesus the unborn awaits birth in Bethlehem. I explained to my friends that this story resonates with my own experience of bringing children into the world. Mortal incarnation is a process, not a moment. It belongs to me and my God.

When we three parted that night, we hadn’t convinced each other of anything except that this time together was precious.

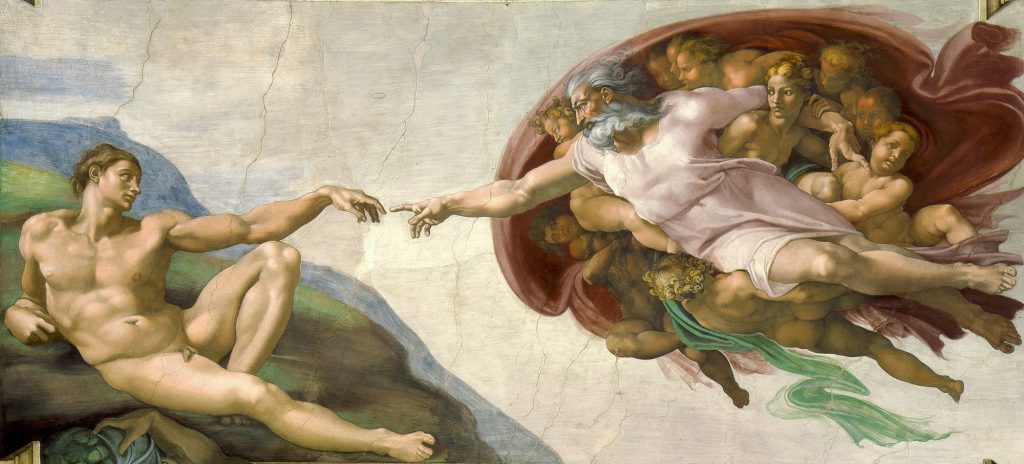

Last December, as I was preparing our empty nest for the Christmastime return of children and grandchildren, I found myself in need of something heavy to flatten out the curving edge of a basement rug. I turned to a shelf of neglected college books and found Michelangelo, the Painter by Valerio Mariani. It is a comprehensive tome, much of its attention given to the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The book gave a satisfying thump as I dropped it onto the carpet, the perfect tool for the job. It lay there, weighing down the carpet for a week until, prompted by my recent search for understanding around creation, I lugged the book upstairs.

Curling up in my reading chair, I opened the book on my lap. Carefully turning the pages, I made my way through colorplate after colorplate to The Creation of Adam, an image that has become iconic in Western culture. The Lord is on the move through the cosmos to bring life to Adam. The wind blows back God’s hair and beard. His celestial clothing ripples. Bearing him up and attending to his royal drapery, seraphim and cherubim play entourage.

I have always loved this painting for its contrast: God’s overflowing force of creation approaches Adam’s lifeless body. Adam’s delicate, downturned hand awaits quickening. But this time around, I saw more. Adam’s body lies in beautiful Renaissance repose, yes, but lifeless? No. His muscles are defined; his flesh is the same golden chiaroscuro tones as the Lord’s. Adam’s eyes do not stare blankly; he’s looking straight at God. Certainly his heart is beating. Yet just as certainly, something is still missing. Although Adam’s body looks youthful and strong, he has no soul.

I look back at God and his crew. Tucked under his arm is a figure different from the angels. A mature woman. It’s Eve, and she’s paying close attention to God’s outstretched hand. It is as if he has told her, “Watch how I do this; it’s going to be your job from now on.” Her eyes are fixed on the most famous detail of this fresco: the fingers that almost touch. Tonight, I am drawn to the space between the fingers: the space between God and the fully incarnate human. I believe that space belongs to women. It is heartbreaking when the state lays claim to it.

I am grateful for the early training I received in managing the tension between my personal spiritual experiences and whatever the current policies of my church may be. I’ve been at this way too long to abandon either my politics or my church. And at this polarized time in American history, people like me—pro-choice members of conservative faith communities—have a special role to play. We can bear witness to the sanctity of female reproductive agency, not in spite of but because of our religion. We can march, fund, and vote in the public square. But it is crucial that we do all these things while staying in relationship with our pro-life brothers, sisters, and siblings within and without our churches. We do this best the way we always have: by serving, praying, and caring together. Like saints in a Renaissance painting who gather round an altar, we must engage in holy conversation, pondering God’s will for a mother and a child.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Spencer W. Kimball, “Guidelines to Carry Forth the Work of God in Cleanliness,” Apr. 1974.

[2] Russell M. Nelson, “Constancy amid Change,” Oct. 1993.

[3] James 1:5.

[4] Eliza R. Snow, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Company, 1884), 46. See also The Teachings of Lorenzo Snow, edited by Clyde J. Williams (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1996), 1–9.

[5] 3 Nephi 1:13.

[post_title] => Eve’s Choice [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 56.3 (Fall 2023): 133–150But Betsy was born. She was dangerously premature—especially so for those days. Everyone said that at birth she could have fit on a dinner plate (an image that haunted my young imagination). She wasn’t expected to survive. But she did. Perfect, whole, healthy. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => eves-choice [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2023-11-13 17:30:40 [post_modified_gmt] => 2023-11-13 17:30:40 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=34923 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

The Other Crime: Abortion and Contraception in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Utah

Amanda Hendrix-Komoto

Dialogue 53.1 (Spring 2020): 33–47

In this essay, I discuss this history, present evidence that Latter-day Saint men sold abortion pills in the late nineteenth century, and argue that it is likely some Latter-day Saint women took them in an attempt to restore menstrual cycles that anemia, pregnancy, or illness had temporarily “stopped.” Women living in the twenty-first century are unable to access these earlier understandings of pregnancy because the way we understand pregnancy has changed as a result of debates over the criminalization of abortion and the development of ultrasound technology.

On a shelf in my office, I have a small red container marked “Chichester’s English Red Cross Diamond Brand Pennyroyal Pills.” I bought it in a moment of curiosity after learning that Utah’s newspapers once advertised abortion pills. The inside of the tin features a woman reclining on a moon. She promises consumers that Chichester’s pills “are the most powerful and reliable emmenagogue known” and are “safe, sure and always effectual.” Students rarely, if ever, notice the box, which sits in front of a Christmas ornament honoring Jeannette Rankin, an early female politician and pacifist from Montana, and next to a potato scrubber. Even if they did, it is unlikely that they would guess that it was a container for abortion pills.

Since graduate school, I have been friends with several women whose academic work focuses on reproductive justice. In a particularly poignant piece, my friend Lauren MacIvor Thompson connects a man “punching his wife when she didn’t undress fast enough for sex” to his support for a fetal heartbeat bill.[1] Although I have been interested in the history of abortion and contraception for several years, I have not joined my colleagues in publishing on the subject. I feared that I would not be able to write a piece that was interesting to both academics and popular audiences and that the politically divisive nature of the topic would alienate people I needed to support me as a junior scholar.

My friends’ engagement with public history, however, has convinced me of the need to engage with wider audiences. On social media and in an article published in the New York Times, for example, MacIvor Thompson has argued for the importance of detailed historical analysis when discussing abortion and birth control. Her deft exposition of the coded language that women used to discuss abortion in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries demonstrates the need for historical expertise when analyzing women’s history.[2] Discussions of abortion and birth control within Latter-day Saint communities, however, often lack the historical awareness for which MacIvor Thompson and others have called.[3] This essay is an attempt to provide an overview of scholarship on the history of contraception and abortion as it relates to Latter-day Saint women.

Before the mid-nineteenth century, most people did not consider a fetus to be “alive” before it quickened, nor was first-trimester abortion illegal. Most authorities considered birth control and abortion to be under the purview of midwives and part of women’s health care.[4] Latter-day Saint understandings of women’s bodies and pregnancy closely mirrored those of other Americans at the time. In this essay, I discuss this history, present evidence that Latter-day Saint men sold abortion pills in the late nineteenth century, and argue that it is likely some Latter-day Saint women took them in an attempt to restore menstrual cycles that anemia, pregnancy, or illness had temporarily “stopped.” Women living in the twenty-first century are unable to access these earlier understandings of pregnancy because the way we understand pregnancy has changed as a result of debates over the criminalization of abortion and the development of ultrasound technology. Reconstructing this history is important, however, because it provides a context for our own discussions of women’s bodies and reproductive rights. Too often, these discussions are ahistorical, and Latter-day Saints and their neighbors act as though society has always understood women’s bodies, pregnancy, and the origins of life in the same way.

One of the things that I have learned from my colleagues is that abortion was once fairly common and unremarkable. Until recently, there was no way for a woman to know for certain that she was pregnant until she felt the baby quicken or move. A woman whose period had stopped might be experiencing malnutrition or illness, or she might be pregnant.[5] If women saw the cessation of their menses as a sign of ill health, they could take medicine to restore their menstrual flow. Sometimes these medicines induced an abortion; at other times, they likely provoked menstruation in women who were anemic or malnourished. It was impossible to distinguish between these two outcomes. As historian John Riddle argues in his own discussion of the issue, a medieval woman “could not possibly know whether she had assisted a natural process or terminated a very early pregnancy.” Nor would she have framed the question in that way. In the medieval period, women and doctors did not see “pregnancy” as starting “at conception or implantation.” [6] Indeed, early signs of pregnancy were ambiguous. According to an online exhibit by Tatjana Buklijas and Nick Hopwood, women in the medieval and early modern periods lived “perched between good growth and evil stagnation” of their bodily fluids.[7] The authors make the same point as Riddle about differing definitions of pregnancy and the inability of women in that time period to differentiate between an early abortion and late menstruation. The ambiguity in which women lived was a part of their daily experience and points to the gap between their experiences and ours.

Women have long practiced contraception and abortion. John Riddle describes an affair between a Catholic priest and a widow in fourteenth-century France that has provided scholars with information about late-medieval birth control. Inquisition records suggest that the priest often brought “with him [an] herb wrapped in a linen cloth” whenever they had sex. He placed it on “a long string,” which hung from her neck “between [her] breasts.” It is unclear how exactly the herb worked, but Riddle argues that the priest likely placed it in her vagina.[8] Although the priest was eventually accused of heresy, these accusations should not blind us to the existence of birth control in medieval Europe. Medieval women used a variety of contraceptive methods, including the withdrawal method, to prevent pregnancy.[9] A ninth-century medical text also contains directions for restoring the menses.[10] Centuries later, women in the nineteenth-century United States used teas made from pennyroyal to induce miscarriages. One of my students tells a story of her rural Wyoming grandmother making her own pessaries in the 1930s, which an unfortunate visitor once mistook for treats (much to his dismay).[11] What these examples demonstrate is that knowledge circulated between women in a variety of places and contexts about how to prevent pregnancies and how to use items from their kitchens to do so.

Understandings of abortion and pregnancy began to change in the mid-nineteenth century. Male physicians launched a campaign to redefine how women thought of their bodies and abortion.[12] Historians like Jennifer Holland, Leslie Reagan, and Judith Leavitt have argued that the campaign was ultimately about the prestige of male doctors and academics who sought to establish themselves as authorities over women’s reproductive health.[13] In the 1850s, the American Medical Association (AMA) began a campaign to criminalize abortion and discredit midwives. In an article on “criminal abortion,” the AMA asserted “the independent and actual existence of the child before birth, as a living being” and urged people to protect that life.[14] The famous American phrenologist Orson Squire Fowler accused a particularly famous purveyor of female pills of “destroying the lives of both mothers and embryo human beings to an incredible extent.”[15] He advocated for her arrest in print. “If human life,” he wrote, “should be protected by law—if murderers should be punished by law’s most severe penalties—she surely should be punished, and her deathly practice be at once arrested.”[16] In the second half of the nineteenth century, states began to pass laws criminalizing abortion. It is important to note here, as Holland has done, that the emphasis on the “life” of the fetus “was not a result of any advancements in embryonic knowledge. In fact, there were none during these campaigns.”[17]

The first generations of Latter-day Saints developed their understanding of pregnancy during this tumultuous time period. Their understandings of the body, however, do not fit easily within this timeline. On the one hand, Latter-day Saints believed that the soul was not created at the same time as the physical body. Instead, they believed that the soul existed before it became embodied in human flesh.[18] Orson Pratt, for example, argued in 1853 that human souls “were present when the foundations of the earth were laid” and “sang and shouted for joy” as they watched creation. He believed that an individual’s body became enjoined with their soul in the womb.[19] Two decades later, Brigham Young identified quickening as the moment when a fetus became alive during a funeral sermon for a Latter-day Saint named Thomas Williams. He told the mourners that “when the mother feels life come to her infant, it is the spirit entering the body preparatory to the immortal existence.”[20] These statements by Young and Pratt were perfectly consonant with the understandings of pregnancy widely accepted during the early modern period, which had placed the beginning of life at quickening and accepted abortion in the first trimester as a return of menstruation.

Latter-day Saint leaders, however, also made speeches denouncing abortion despite the fact that their theology did not necessarily require doing so. In 1867, Young explicitly decried attempts to avoid infanticide through “the other equally great crime.” Some scholars have interpreted his statement as a reference to abortion, but he could also be referring to birth control.[21] In 1884, Erastus Snow lauded Latter-day Saint women for refusing to patronize “the vendor of noxious, poisonous, destructive medicines to procure abortion, infanticide, child murder, and other wicked devices.”[22] Snow and Young never explicitly define abortion, but it appears that they accepted the arguments of the American Medical Association decrying abortion even as they rejected their position about when life began.

It is important, however, not to just examine the sermons and speeches of elite Latter-day Saint men. Although Latter-day Saint leaders railed against abortion, there is evidence that some of their female followers took medications to regulate their periods and did so without much censure. In 1896, a Latter-day Saint female physician named Hannah Sorensen published an obstetrical textbook designed to provide women with information about their bodies. She had attended medical school in Denmark in the 1860s before converting to the LDS Church and traveling to Utah, where she set up a practice.[23] Sorensen accused the Latter-day Saint patients she saw in her practice as having “a terrible misunderstanding in regard to foetal life.” Perhaps with dis belief or even disdain, she wrote, “Many believe it is no sin to produce abortion before there is life, but there is always life.”[24] Her descriptions of her encounters with Latter-day Saint women suggest that some of them agreed with their contemporaries that quickening represented the soul coming into the body of an infant and did not see early abortion as a moral issue.

Like their counterparts throughout the United States, Utah newspapers advertised abortion pills. Increasing restrictions on abortion and birth control meant that the advertisements used euphemisms to refer to the pills’ effects, but they were ubiquitous. A quick newspaper search using the database Newspapers.com reveals advertisements in a long list of Utah newspapers, including the Salt Lake Tribune, the Daily Enquirer (Provo), the Standard (Ogden), the Wasatch Wave (Heber), the Ephraim Enterprise, the Broad Ax (Salt Lake City), the Transcript Bulletin (Tooele), and the Deseret Evening News (Salt Lake City).[25] Reed Smoot, a future Utah senator and member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, owned a drug company in Provo that sold Mesmin’s French Female Pills. An ad in the Provo Daily Enquirer styled the pills “The Ladies’ Friend” and promised “immediate relief of Painful, and Irregular Menses, Female Weakness etc.”[26] The Deseret Evening News assured women in 1910 that Dr. Martel’s Female Pills could be found “for sale at all drug stores.”[27] And, as a final example, a British convert named William Driver stocked Dr. Mott’s Pennyroyal Pills in his store in Ogden, Utah.[28] Although I have been unable to find a direct statement from a Latter-day Saint woman describing her experience taking female pills, it is likely that some women did so. Otherwise, Hannah Sorensen would have had no reason to lodge her complaint and Latter-day Saint businessmen would not have stocked them.

Sorensen found this situation troubling. In her obstetrical text book, she dismissed the idea that it was “no sin” to have an abortion before quickening by arguing that “life” existed “from the moment of conception.”[29] She also tried to convince Latter-day Saint women of the rightness of her position by giving classes on the subject. The notes that women took during her lectures and classes give us a window into changing Latter-day Saint attitudes about women and pregnancy. The George Teasdale collection contains the notes that Rosa B. Hayes took while listening to Sorensen lecture in 1889. Her notes locate the origins of pregnancy in the first moments after conception. Immediately after this event, she notes, “great changes take place in the system, causing many little troubles and ailments.”[30] “All ther [sic] nature,” she continued, “is in sympathy with, and lends assistance to develop the new being.”[31] She encouraged any pregnant woman to “ask Him to help her observe all the rules of nature, keep her mind placid, and contemplate on the future of her offspring.”[32] Women were to avoid eating “pork, pickles, beans, onions, bacon, unripe fruit, mustard, horse radish, cabbage, tea, coffee and all other stimulants.”[33] Sex was also forbidden as was her usual routine of “hard work.”[34] This new understanding of pregnancy encouraged women to see their bodies as vessels for potential life. It is difficult to know how Latter-day Saint women as a whole responded to Sorensen’s lectures and classes. While women like Rosa Hayes welcomed Sorensen’s information, others likely rejected it as nonsense. The latter were unlikely to leave records of their opinions.

By the late nineteenth century, attitudes surrounding abortion had already begun to change. Within a few decades, Latter-day Saint women would experience increased pressure to have large families. The Relief Society Magazine published a series of statements from members of the Quorum of Twelve on birth control in its July 1916 issue. Rudger Clawson called the decision to limit family size “a serious evil”—“especially among the rich who have ample means to support large families.”[35] Joseph Fielding Smith argued that “it is just as much murder to destroy life before as it is after birth.”[36] Likewise, Orson F. Whitney wrote that “the only legitimate ‘birth control’ [was] that which springs naturally from the observance of divine laws.”[37] The frontispiece featured a collage of young children and infants as an explicit argument for the value of children. It is difficult for women born in the twentieth or twenty-first centuries to imagine how women living in earlier time periods experienced pregnancy. Modern photography and ultrasound technology have transformed how we understand early pregnancy. In 1965, Life magazine published an emblematic set of photos of the fetus. The images invited people to imagine fetuses at each stage of development. One depicted an eighteen-week-old fetus, in the words of one historian, “radiant and floating in a bubble-like amniotic sac.” The same historian continues, “It is the image of a sleeping infant, eyes closed, head turned to the side, petite and glowing against a black background flecked with star-like matter.”[38]

Around the same time, doctors began to “see” inside the womb using ultrasound technology. Newspapers around the United States printed articles about the innovation’s promise: one woman from a Boston suburb discovered that she was having twins; a doctor in Colorado urged its use in conjunction with amniocentesis to diagnose Down syndrome; and an Alaska hospital used it to predict difficult deliveries.[39] Ultrasound has given us the illusion of direct access to the womb and has created the idea that the infant is a separate patient from its mother.[40] Before the mid-twentieth century, women did not have access to these technologies and saw early pregnancy as an indeterminate state.

It is difficult to recapture the uncertainty that existed around early pregnancy in the nineteenth century. It is impossible to remove ourselves from the technologies and cultural concepts that shape our relationships to our bodies and pregnancies. I became pregnant with my second child at a difficult time in my life. I had just started a tenure-track job and was struggling to connect to people at the university. After I took the pregnancy test, I remember thinking that no matter what happened that it would be me and this child. My thoughts were directed at an embryo that was just a few weeks old. Although I like to imagine those thoughts as completely my own, they were made possible by decades of imagining the fetus as a separate being. Changing understandings of pregnancy have also shaped how Latter-day Saints relate to their bodies. Like their non-Mormon sisters, Latter-day Saint women initially placed the beginning of life in the womb at quickening and likely used a variety of herbal remedies to regulate their periods and pregnancy. Debates over abortion in the second half of the nineteenth century politicized women’s control over their bodies and created the idea of conception as the moment in which individual human lives began. The current stance of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on abortion is that “human life is a sacred gift from God” and that “elective abortion for personal or social convenience is contrary to the will and the commandments of God.”[41] It is important to remember, however, that Latter-day Saints have not always agreed on when life began and, as a result, have not always accepted that early abortion is a sin. It is important to ground our discussions of abortion and reproductive rights in a historical context. Too often, these conversations proceed as though our understandings of women’s bodies and the nature of life within the womb are self-evident.

[1] Lauren MacIvor Thompson, “Women Have Fought to Legalize Reproductive Rights for Nearly Two Centuries,” History News Network, June 9, 2019, https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/172181. Dr. MacIvor Thompson has also pointed out in private conversations with me that heartbeat is inaccurate and puts the word in quotation marks in her own article. At six weeks of gestation, the fetus does not have a fully formed heart. Instead, what we see on an ultrasound is the electrical activity of the cells that will eventually become the heart. For a full explanation of the misleading nature of the term “heartbeat” and its use in contemporary politics, see “Doctor’s Organization: Calling Abortion Bans ‘Fetal Heartbeat Bills’ is Misleading,” Guardian, June 5, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/05 /abortion-doctors-fetal-heartbeat-bills-language-misleading.

[2] See Lauren MacIvor Thompson (@lmacthompson1), “1/Good morning! I am compelled to write my first ever tweet thread because @CokieRoberts on @NPR this morning stated that she could not find abortion ads in 19thc newspapers and therefore historians are just playing at pro-choice politics,” Twitter, June 5, 2019, 6:26 a.m., https://twitter.com/lmacthompson1/status/1136247963817304064; and MacIvor Thompson, “Women Have Always Had Abortions,” New York Times, Dec. 13, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/13/opinion/sunday/abortion-history-women.html.

[3] I have chosen to use the Church’s style guide as much as possible for this article. Since I am not a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, it seemed important to try respect the Church’s wishes as much as possible, especially when dealing with a sensitive topic such as this one.

[4] Tatjana Buklijas and Nick Hopwood, “Experiencing Pregnancy,” Making Visible Embryos (website), http://www.sites.hps.cam.ac.uk/visibleembryos /s1_1.html.

[5] John M. Riddle, Eve’s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 26.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Buklijas and Hopwood, “Experiencing Pregnancy.”

[8] Quoted in Riddle, Eve’s Herbs, 22–23.

[9] Maryanne Kowaleski, “Gendering Demographic Change in the Middle Ages,” The Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe, edited by Judith M. Bennett and Ruth Mazo Karras (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 190.

[10] Jessica Cale, “Sex, Contraception, and Abortion in Medieval England,” Dirty, Sexy History (blog), July 17, 2017, https://dirtysexyhistory.com/2017/07/30/sex -contraception-and-abortion-in-medieval-england/; Hunter S. Jones, et al., Sexuality and its Impact on History: The British Stripped Bare (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword History, 2018), 62.

[11] Andi Powers, “Bitter Lessons,” High Altitude History (blog), Mar. 8, 2017, https://historymsu.wordpress.com/2017/03/08/bitter-lessons-andi-powers/.

[12] Jennifer L. Holland, “Abolishing Abortion: The History of the Pro-Life Movement in America,” American Historian, Nov. 2016, https://tah.oah.org/november-2016/abolishing-abortion-the-history-of-the-pro-life-movement-in-america/.

[13] Holland, “Abolishing Abortion;” Leslie J. Reagan, When Abortion was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867–1973 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); and Judith Walzer Leavitt, Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America, 1750–1950 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986).

[14] Cited in D. Brian Scarnecchia, Bioethics, Law, and Human Life Issues: A Catholic Perspective on Marriage, Family, Contraception, Abortion, Reproductive Technology, and Death and Dying (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2010), 280.

[15] Orson Squire Fowler, Love and Parentage: Applied to the Improvement of Offspring (New York: Fowlers and Wells, 1852), 68.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Holland, “Abolishing Abortion”; Reagan, When Abortion was a Crime; Leavitt, Brought to Bed.

[18] Terryl L. Givens, When Souls Had Wings: Pre-Mortal Existence in Western Thought (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[19] Orson Pratt, “The Pre-existence of Man,” Seer 1, no. 2 (February 1853): 20. Thank you to Matthew Bowman for pointing me toward this source.

[20] Brigham Young, July 19, 1874, Journal of Discourses, 17:143.

[21] Brigham Young, Aug. 17, 1867, Journal of Discourses, 12:120. See Peggy Fletcher Stack, “Surprise! The LDS Church Can Be Seen as More ‘Pro-Choice’ than Pro-Life on Abortion. Here’s Why,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 1, 2019, https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2019/06/01/surprise-lds-church-can/; and Lynn D. Wardle, “Teaching Correct Principles: The Experience of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Responding to Widespread Social Acceptance of Elective Abortion,” BYU Studies Quarterly 53, no. 1 (Jan. 2014): 112.

[22] Erastus Snow, Mar. 9, 1884, Journal of Discourses, 25:111–12. Although I have consulted the Journal of Discourses for these citations, many of them have been previously refenced by Lester Bush, and readers would do well to reference his work. See Lester E. Bush, Jr., “Birth Control among the Mormons: Introduction to an Insistent Question,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 10, no. 2 (1976): 12–44.

[23] Robert S. McPherson and Mary Lou Mueller, “Divine Duty: Hannah Sorensen and Midwifery in Southeastern Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 65, no. 4 (1997): 336.

[24] Hannah Sorensen, What Women Should Know (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon & Sons Company, 1896), 80.

[25] In this case, I used Newspapers.com to find these examples, but a similar search could be performed using Chronicling America (chroniclingamerica.loc.gov) or any number of sites.

[26] Advertisement, Daily Enquirer 7, no. 88, Apr. 10, 1893, 2, available at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/42896775/.

[27] Advertisement, Deseret Evening News, Sept. 12, 1910, 9, available at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/42896791/.

[28] Advertisement, Standard, May 2, 1893, 2, available at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/42896809/.

[29] Sorensen, What Women Should Know, 80.

[30] Rosa B. Hayes, Midwife Instruction Book, 1889, p. 24, George Teasdale Papers, box 21, folder 5, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[31] Ibid., 24.

[32] Ibid., 26.

[33] Ibid., 29.

[34] Ibid., 31.

[35] “Birth Control,” Relief Society Magazine 3, no. 7 (July 1916): 364.

[36] Ibid., 368.

[37] Ibid., 367.

[38] Ann Neumann, “The Visual Politics of Abortion,” The Revealer (blog), Mar. 8, 2017, https://therevealer.org/the-patient-body-visual-politics-of-abortion/ For the original images, see Lennart Nilsson, “Drama of Life Before Birth,” Life, Apr. 30, 1965, 54–71.

[39] Respectively, “Ultrasound Tells Mom ‘Twins Due,’” Ogden Standard-Examiner, Nov. 14, 1971, 12, available at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/42901981/; Joanne Koch, “Tests are Urged for Late Pregnancies,” Daily Times-News (Burlington, N.C.), Jan. 28, 1976, 11A, available at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/42902070/; and Diane Simmons, “Hospital Squeeze is Result of More Patients, More Deliveries,” Fairbanks Daily News, Mar. 24, 1976, A-11, available at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/42902070/.

[40] For analyses of the role ultrasound has played in changing pregnancy, see Barbara Duden, Disembodying Women: Perspectives on Pregnancy and the Unborn, translated by Lee Hoinacki (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993); Malcolm Nicolson and John E. E. Fleming, Imaging and Imagining the Fetus: The Development of Obstetric Ultrasound (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013); and Sarah Dubow, Ourselves Unborn: A History of the Fetus in Modern America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[41] “Abortion,” Gospel Topics, accessed Sept. 29, 2019, available at https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-topics/abortion?lang=eng.

[post_title] => The Other Crime: Abortion and Contraception in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Utah [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 53.1 (Spring 2020): 33–47In this essay, I discuss this history, present evidence that Latter-day Saint men sold abortion pills in the late nineteenth century, and argue that it is likely some Latter-day Saint women took them in an attempt to restore menstrual cycles that anemia, pregnancy, or illness had temporarily “stopped.” Women living in the twenty-first century are unable to access these earlier understandings of pregnancy because the way we understand pregnancy has changed as a result of debates over the criminalization of abortion and the development of ultrasound technology. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => the-other-crime-abortion-and-contraception-in-nineteenth-and-twentieth-century-utah [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-11-21 01:15:59 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-11-21 01:15:59 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=25875 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Premortal Spirits: Implications for Cloning, Abortion, Evolution, and Extinction

Kent C. Condie

Dialogue 39.1 (Spring 2006): 1–18

Perhaps no other moral issue divides the American public more than abortion. In part, the controversy hinges on the question of when the spirit enters the body. If a spirit were predestined for a given mortalbody and that body is aborted before birth, the spirit would, technically,never be able to have a mortal existence.

Any organism (animal or plant) living on Earth today or any organism that lived on Earth in the geologic past is largely the product of its genes, which in turn are inherited from two parents—or, in the case of asexual reproduction, one parent. No other parents can produce this organism. Hence, if each organism is patterned precisely after a spiritual precursor, as we are commonly led to believe by some interpretations of Moses 3:5, only one set of parents can produce this organism in the temporal world. Carried further, this scenario means that all of our spouses and children are predestined from the spirit world and that we really have not exercised free agency in selecting a mate or in having children in this life. It also means that each plant and animal that has ever lived on Earth was predestined to come from one or two specific parents. This would also seem to require that events in Earth history are predestined, because specific events are necessary to bring predestined individuals into contact with each other in the right time frame.

But how can a predestined or deterministic temporal world be consistent with traditional LDS belief in free agency? From the very onset of the restoration of the LDS Church, Joseph Smith taught that God "did not elect or predestinate."[1] As Bruce R. McConkie states, "Predestination is the false doctrine that from all eternity God has ordered whatever comes to pass."[2] Determinism advocates that all earthly events are controlled by prior events (usually in the premortal existence), but not necessarily by God. Although L. Rex Sears makes a case for compatibility of free agency and determinism, Blake Ostler shows that his arguments are easily refuted.[3] Also, many basic LDS doctrines are at odds with both predestination and determinism.

Although free agency and predestination/determinism are generally considered mutually exclusive, LDS teachings and scriptures often do not clarify inconsistencies in these concepts as applied to the preexistence and to God's foreknowledge. In this paper, I examine and explore ways to reconcile inconsistencies by proposing a model for premortal spirits. The viability of the model can be tested against scriptures and scientific observations. If we find factual information that the model cannot explain, then it must be modified or abandoned. The model I propose is that premortal spirits are not predestined for specific mortal bodies, an idea earlier suggested by Frank Salisbury.[4] At present, I know of no evidence, scriptural or scientific, that would require rejecting the model outright. As with scientific models, however, future information may require modification or rejection.

I also discuss questions about cloning, abortion, evolution, and extinction related to the predestination question. This contribution, however, is not intended to be a discussion of predestination, free agency, or God's foreknowledge, all of which have been discussed from an LDS point of view in recent articles and books, many of which are cited herein.

The Spiritual Creation: Spirit-Body Relationships

Many LDS writers have speculated on how spiritual and temporal bodies are related. Most conclude that the earthly body is identical or nearly identical to the spiritual body.[5] Parley P. Pratt was one of the earliest LDS theologians to comment on this subject: "The spirit of man consists of an organization or embodiment of the elements of spiritual matter, in the likeness and after the pattern of the fleshly tabernacle. It possesses, in fact, all the organs and parts exactly corresponding to the outward tabernacle."[6] The most definitive statement is by the First Presidency in 1909: "The spirit of man is in the form of man, and the spirits of all creatures are in the likeness of their bodies."[7] Also, almost all Mormons agree that spirits have gender, a concept most recently stated by President Gordon B. Hinckley in general conference: "All human beings—male and female—are created in the image of God. Each is a beloved spirit son or daughter of heavenly parents, and as such, each has a divine nature and destiny. Gender is an essential characteristic of individual premortal, mortal, and eternal identity and purpose."[8]

However, as discussed by Duane Jeffery and Jeffrey Keller, the gender of an earthly body is not always clearly defined.[9] For instance, what is the gender of spirits who reside in the bodies of hermaphrodites (individuals with male and female sex organs) or in individuals who were males in the preexistence, but in this life have a female body and are raised as females? What about individuals who undergo a sex change? Could it be that some individuals may have a spirit gender different from their temporal gender?

Premortal Spirits: A Testable Hypothesis

There may be a way around the predestination problem if the spirits God creates are not predestined for specific organisms. In this case, a premortal spirit is really a nonspecific spirit in that it is not intended for any specific organism but can be placed in any one of many different organisms in a similar taxonomic group at approximately the same degree of complexity within this group. For instance, very simple spirits would be placed in unicellular organisms (like bacteria), while very complex spirits would be placed in mammals. However, because all gradations exist between taxonomic groups, there also must be all gradations between spirits. An important implication of the premortal model is that no premortal spirit, simple, intermediate, or complex, is predestined to be placed in any specific organism. When nonpredestined spirits are placed in embryos of humans they would develop along with the embryo and fetus. These spirits inherit individual mental and spiritual attributes from the intelligences they contain. As a human grows and develops during his or her lifetime, his or her spirit also "grows," at least in terms of mental and spiritual capacities, if not in terms of size and shape. It is now the specific spirit of its host, and only one such organism will ever live on this planet or any place else. For instance, the spirit that was placed in the embryo or fetus that became Joseph Smith was not predestined for Joseph; but once placed in that embryo or fetus, it became the specific and eternal spirit of Joseph Smith.

We are told in Abraham 5 and in Moses 2 and 3 that God created everything spiritually before it was created temporally. Just what this means, however, is not entirely clear, since the time interval between the two creations is not specified. It could be billions of years or it could be microseconds. In referring to Abraham 3:22-28, Joseph Fielding Smith favored a long time between the two creations: "We were all created untold ages before we were placed on this Earth."[10] However, perhaps not all human spirits were present when the plan of salvation was presented in the preexistence. There are no scriptures to my knowledge that eliminate the possibility that spirits are still being created. We are told that God creates spirits from "intelligences," which have always existed (Abr. 3:22-23; D&C 93:29-30). A minority viewpoint in the LDS Church, as championed by Bruce R. McConkie, who followed Joseph Fielding Smith on this point, is that "the intelligence or spirit element became intelligences after the spirits were born as individual entities."[11] As Joseph Smith taught, however, "Intelligence is eternal and exists upon a self-existent principle."[12] According to B. H. Roberts:

Intelligences are uncreated entities; some inhabiting spiritual bodies; others are intelligences unembodied in either spirit bodies or other kinds of bodies. They are uncreated, self-existent entities, necessarily self-conscious. . . . They possess powers of comparison and discrimination—they discern between evil and good; between good and better; they possess will or freedom. . . . The individual intelligence can think his own thoughts, act wisely or foolishly; do right or wrong.[13]

Thus, in Roberts's view, intelligences must possess self-consciousness, the power to compare, and the power to chose one thing instead of another. Whether intelligences possess gender, however, is not known. As summarized by Rex Sears: "The God of Mormonism lives in a universe and among intelligences not of his own making. God acquires the ability to predict our behavior only by getting to know us; when meeting an intelligence for the first time, as it were, God does not know if things will work out with that intelligence."[14]

We know very little about how or when spirits were created or whether they are still being created, a fact that has a bearing on the question of predestination. It is a common belief among Mormons that God placed each intelligence in a spirit intended for a specific temporal organ ism as suggested by Doctrine and Covenants 77:2: ". . . that which is spiritual being in the likeness of that which is temporal; and that which is temporal in the likeness of that which is spiritual; the spirit of man in the likeness of his person, as also the spirit of the beast, and every other creature which God has created." This sounds a lot like predestination.

However, this interpretation is critically dependent upon when the spirits were created. If they were created at or near the time of the temporal creation, it is not surprising that they would have the "likeness" of the organism in which they were to be housed. In this case, predestination is not an issue. But if spirits are created long before their temporal hosts, we are faced again with the predestination question. If we have a large "spirit pool" containing spirits of all forms of life, this would seem to predestine that all these forms of life must appear on Earth. Yet if mortal organisms are the products of evolution, which is a random process (see below), there is no reason that hosts for premortal spirits should have appeared on Earth. This observation strongly implies to me one or both of the following scenarios: (1) most or all spirits were not created eons before the temporal creation but were created at or near the time that their temporal hosts were created; or (2) God creates spirits as generic groups with no one spirit intended for a specific temporal organism.

Still another question is just how God decides which spirits to place in which mortal bodies. Some human spirits are placed in fetuses with inherited diseases or missing body parts. Some go into children born into rich families. Others go into children born into poor families. Some go into black children, others into white children or other races. Some go into females, others into males, bisexuals, and homosexuals. Some spirits enter bodies that are members of primitive societies, whereas others enter bodies in highly technical societies of the twenty-first century. Clearly not all humans have equal chances of survival or comparably enjoyable lives. Does God discriminate against some spirits and favor others, based perhaps on their performances in the preexistence?

Although many LDS members believe that our status and the nature of the body we have in this life depend on our performance in the preexistence, I do not share this point of view. The God I believe in is fair and does not purposefully discriminate among spirits. Just how he decides which spirit to place in which body is unknown. One possibility is that he randomly selects spirits or intelligences, thus giving each one an equal chance at where it ends up in this life. A common LDS belief, although not well-supported by scripture, is that the "choicest" spirits are reserved for the latter days. However, this belief again brings up the predestination question—i.e., some spirits are predestined for the latter days.

Can the idea of nonpredestined premortal spirits be accommodated within LDS doctrine? I think it can; and in the following sections, I test the concept against various LDS scriptures and teachings and explore more fully the ramifications of such an idea.

The Preexistence

The relationship between the spiritual creation and the temporal creation has a close bearing on the nonpredestined spirit model. There are several interpretations about which scriptures refer to the spiritual creation and which to the temporal creation.[15] Milton R. Hunter, Bruce R. McConkie, and Joseph Fielding Smith interpret Abraham 4-5 as referring to the spiritual creation and Moses 2-3 and Genesis 2 as recording the temporal creation.[16] In contrast, J. Reuben Clark and W. Cleon Skousen read the Moses and Genesis accounts as referring to the spiritual creation, saying little about the temporal creation.[17] Others seem to think that both the spiritual and temporal creations are recorded in Moses and Genesis.[18] Despite these differences, most LDS scripturalists agree on two aspects of the creation accounts: (1) the temporal creation was patterned at least in some degree after the spiritual creation, and (2) all living things were created spiritually before they were created temporally.

A critical question for the nonpredestined spirit model is just how closely the spiritual creation served as a "blueprint" for the temporal creation. If the correspondence was exact, as some believe,[19] we are again faced with the predestination problem. On the other hand, if the spiritual creation was simply a general outline for the temporal creation or if spirits are created at or immediately before the creation of their temporal hosts, we may be able to sidestep the predestination issue. In either case, I suggest that the spiritual creation was and is the creation of spirits not predestined for a specific temporal home.

We are told of a great war in the preexistence (D&C 29:36-38; Rev. 12:7), suggesting that at least some part of the spiritual creation preceded the temporal creation. If the great war story is taken at face value, it would appear that approximately one third of the hosts of heaven followed Satan, and thus their spirits will never enter earthly bodies. The other two thirds of the spirits, however, have been or will be placed in earthly bodies. Joseph Smith and other Church presidents made statements suggesting that some human spirits "excelled" in the preexistence and that their placement in a specific terrestrial body reflects, at least in part, their progress in the preexistence.[20]

How does a great war and the progression of spirits in the preexistence constrain the nonpredestined spirit model? If interpreted literally, it implies enough time between the spiritual and temporal creations for at least some humans to have progressed while they were in the spirit world. James E. Talmage also implies this concept.[21] Single spirits, much like single soldiers in an army, have individual differences because they house intelligences with individual differences. Given the opportunity in the premortal spirit world, some spirits may have significantly advanced, while others did not.

One of the problems with the great war story, however, is that the spirits who followed Christ and elected to take on a temporal body would seem to have been predestined from that time onwards. If evolution is the process by which organisms appeared on Earth, which seems likely (see below), then evolution had to give rise to a very specific group of mortal humans to house these spirits. Given the random nature of evolution, such a scenario is highly improbable.

One way to get around the predestination problem is if the word "spirit" in the scriptures that refers to premortal existence is misinterpreted. Could these scriptures really be referring to "intelligences," the precursors of spirits? If so, the great war in the preexistence would have occurred before God created spirits. In the same light, it is possible that the progression in the "spirit world" referred to above is really progression in the "intelligence world." There is no obvious reason why progression could not occur in intelligences; in fact, such development would be consistent with the principle of eternal progression, a commonly cited LDS doctrine.

Foreordination and Foreknowledge

The nonpredestined spirit model also helps solve problems related to foreordination and foreknowledge. Foreordination, which is a rather unusual LDS teaching, is the concept that certain spirits were called or as signed in the preexistence to carry out certain functions in this lifetime. Doctrine and Covenants 138:55-56 states that many of the "noble and great ones . . . were chosen even before they were born." We can get around the predestination problem with the caveat that, if spirits are fore ordained to fulfill some duty in this life, they can elect not to do so by exercising their free agency.[22] Another factor to be considered is the possibility that some individuals may not be worthy to carry out their foreordained callings. In either case, the spirit is not predestined for a calling in the mortal world.

If intelligences and spirits can progress in the premortal world, there is no reason that God cannot assign or ask specific intelligences or spirits to perform specific tasks when they arrive in this life.[23] God might pick individual intelligences or spirits that have excelled in certain ways in the preexistence and foreordain them for similar earthly endeavors.[24] However, foreordained intelligences or spirits are not predestined for specific mortal bodies. McConkie argues that God foreordains certain people for certain earthly missions because of the knowledge he has acquired through ages of observation that the person so ordained has the talents and capacities to perform the required task.[25] Perhaps God placed a fore ordained spirit in the embryo that would become Joseph Smith simply because Joseph would be born at the right time and the right place to accomplish the foreordained duties of reestablishing the Church.[26] If Joseph had not met the challenge, however, some other individual of this time period and in this geographic location would have been given that opportunity.

As with predestination, an absolute foreknowledge of God seems inconsistent with free agency. As nicely summarized by Blake Ostler: "A major problem arises if God foresees precisely what must happen. For if I am morally responsible for an action, I must also be free to refrain from doing that action. But if God knows what my action is before I do it, then it is not genuinely possible for me to do otherwise. If the premises are accepted as sound, then foreknowledge and free agency in the stronger sense of freedom of alternative choices are not logically compatible."[27]

Is the idea that a premortal spirit can be placed in any earthly body (and not predestined for a certain one) inconsistent with the concept that God has a foreknowledge of the future? It would seem to be if God's foreknowledge is absolute. In an LDS context, the question of the degree of God's foreknowledge has been extensively discussed.[28] One interpretation of God's omniscience is that he knows everything that can be known and knows how he will respond to various possibilities in the future but does not have an absolute foreknowledge of the future.[29] His omniscience, however, is not limited by what cannot be known at a given time. Talmage suggests that God's foreknowledge is not absolute and does not necessitate predestination but that "God's foreknowledge is based on intelligence and reason. God foresees the future as a state which naturally and surely will be; but not as one that must be because He has arbitrarily willed that it shall be."[30] B. H. Roberts also suggests that God knows all that is known, which includes all that is or has been, but that he does not know the future in an absolute sense until it arrives.[31] Ostler supports the concept of "existentially contingent omniscience," meaning that God now knows all possibilities but does not know precisely which possibilities will be chosen in the future.[32] For free agency to exist, alternatives in the future must exist. They must be real alternatives and not just "apparent" alternatives as would be the case if God had an absolute foreknowledge. If these interpretations of God's foreknowledge are correct, then premortal spirits are not predestined for a given mortal body nor for a given mortal event.

Before leaving this topic, it is necessary to mention the philosophy of "timelessness" in respect to God. The idea that God is timeless (in the sense that for God there is no past, present, or future) has been discussed by both Robson and Ostler.[33] Although a few, Elder Neal A. Maxwell among them, seem to accept a timeless God,[34] many scriptures clearly indicate that God cannot be timeless, a fact superbly summarized by Robson and Ostler.[35] I accept these arguments and, for the purposes of this discussion, do not consider a timeless God as a viable alternative.

Premortal Appearances of Christ

One of the most difficult challenges to the nonpredestined spirit model of the preexistence is abundant scriptural references to Christ's manifestations before his mortal birth. Although Christ (Jehovah) spoke to one or more people prior to his birth (e.g., Moses 1:2; Abr. 2:6-11; 3:11), he appeared in person relatively infrequently. One well-documented incident is his appearance to Mahonri Moriancumer, the brother of Jared: "Behold, this body, which ye now behold, is the body of my spirit; and man have I created after the body of my spirit; and even as I appear unto thee to be in the spirit will I appear unto my people in the flesh" (Eth. 3:16).

How do these premortal appearances of Christ avoid the problem of predestination? If the voice of Jehovah in the Old Testament was indeed that of Christ and if his appearances were in his "mortal form," then the spirit of Christ must have been predestined to enter Christ's mortal body. Romans 8:29-30 suggests that God created Christ's spirit to enter a very specific human being:

For whom he did foreknow, he also did predestinate to be conformed to the image of his Son, that he might be the firstborn among many brethren.

Moreover whom he did predestinate, them he also called: and whom he called, them he also justified: and whom he justified, them he also glorified. (Emphasis mine; see also D&C 93:21; 2 Tim. 1:9.)

If these scriptures are interpreted literally, they imply that the spirit of Christ had the same voice and appearance as the mortal Christ long before there was a mortal Christ.

I can see two ways around this problem that preserve the nonpredestined spirit model for most humans: (1) Christ was different from everyone else—he really was predestined for a certain mortal body; or (2) it was not Christ (Jehovah) who appeared in the Old Testament. The easiest way around the predestination problem is that it applies to everyone except Christ. Certainly Christ is a unique individual in many other ways: having God as a father yet an earthly (perhaps surrogate) mother; showing great leadership capacity in the preexistence (John 17:5); being the only person free from sin; and finally, being the Savior of all humankind. Why not add another exception to the list? In fact, the scripture quoted from Romans specifically states that Christ's spirit was predestined. Perhaps God created a spirit for Christ that could appear and speak to earthly inhabitants with a spirit body identical to the mortal body, which would appear in the future. This also implies that Christ's spirit body, which appeared as an adult to the brother of Jared, could return to some nascent state with a very small size before entering the mortal embryo Christ at a later time.

One problem with this idea emerges if Christ is really half mortal—if half his genes came from Mary. This would seem to predestine Mary to be his mother, which in turn would predestine many events that resulted in Mary being born at the right period of time and in the right place—in short, also predestinating her ancestors. It would seem that the only way around this problem is to have all of Christ's genes come from God and an eternal mother, and none from Mary. This scenario, however, relegates Mary to the role of a surrogate mother, not Christ's biological mother.

Alternatively, the images and voices of Jehovah described in the Old Testament may not have been those of Christ. Rather, God may have im printed in the brains of Old Testament people the image (or/and voice) of a man similar to the way Christ would look or sound as a mortal. It makes no difference in terms of the lessons taught to Old Testament people whether it was really Jehovah's spirit talking to them or some other male voice. This alternative, however, requires that God deceived the individuals in the Old Testament who believed they were hearing or seeing Jehovah.

Cloning

The nonpredestined spirit model may solve doctrinal problems raised by cloning. Cloning is the production of a group of identical cells or organisms that come from a single organism. The genetic "parent" of Dolly, the cloned sheep in Scotland, was the nucleus from a single adult mammary gland cell.[36] Cloning is not new but has been used since the 1970s to produce cattle for breeding.[37] One potential use of cloning is to make human "replacements" for old people or dying relatives, or to make many copies of one's children. Cloning can also be a valuable tool in studying human development, genetically modifying embryos, and developing new organ transplant methods.[38]

Humans can be cloned in at least two ways: (1) split an embryo into several segments, and new individuals develop from each segment—this is the natural method that produces identical twins—and (2) clone cells from a human, thus producing individuals identical to that human. Every cell contains the genetic information to make an entire human being. On December 14, 1998, South Korean scientists of the Seoul Fertility Clinic announced that they had cloned a human embryo.[39] They claim to have inserted a new nucleus in a human egg cell and activated the cell, which reportedly divided twice in vitro before the researchers terminated the experiment. This claim immediately set off a wave of scientific doubt and controversy. Regardless of the outcome of this claim, we are close to the time when a human embryo will be cloned.

Most Christian religions believe in a human soul (spirit + body = soul; D&C 88:15), which brings up the question of whether it is possible to clone the soul. If a person's physical body can be cloned, but not his or her soul, what does this mean for the clone's eternal future? The only official statement of the LDS Church on cloning is ambiguous and not widely available to the general public.[40]

It is interesting to explore some of the ramifications of cloning in light of nonpredestined spirits. I can see no reason why God would refuse to place spirits in human clones and, as with any other human, each clone plus its spirit (i.e., a soul) becomes a specific human being. Although the clone would be anatomically identical or at least very similar to its single "parent," its mental and spiritual qualities could become quite different depending on various environmental factors affecting the clone during its lifetime. Also contributing to divergence from the original organism are different cytoplasm and mitochondria in the clone. We can consider God as the creator of spirits while scientists, by using genetics, could play an important role in controlling and designing the mortal bodies into which some of these spirits are placed. I do not have a problem with this idea. In fact, God may be waiting for us to develop bodies by genetic engineering or cloning to house more advanced or complex spirits that he will create.

Can scientists clone spirits? Of course, we do not have an answer to this question since science cannot detect, identify, or even validate the existence of spirits. However, in the context of LDS doctrine, it seems that God reserves all manipulations of spirits for himself. There are probably enough intelligences or/and premortal spirits that each human-made clone can have its own God-made spirit.

What about unicellular organisms that propagate by cell division? When a cell divides, perhaps its spirit divides also, or alternatively, God may place a new spirit in one or both of the derivative cells.

Abortion

Perhaps no other moral issue divides the American public more than abortion. In part, the controversy hinges on the question of when the spirit enters the body. If a spirit were predestined for a given mortal body and that body is aborted before birth, the spirit would, technically, never be able to have a mortal existence. However, in the nonpredestined scenario, abortion prior to the time the spirit enters the fetus simply means that the spirit would be assigned to another fetus. Thus, the abortion would not prevent this spirit from acquiring a body but would simply transfer it to another fetus prior to birth. Brigham Young carried this idea even further when he stated: "When some people have little children born at 6 & 7 months pregnancy and they live but a few hours then die, they bless them etc. but I don't do it for I think . . . that such a spirit will have a chance of occupying another tabernacle and developing itself."[41] Although this idea does not require that the spirits are not predestined for their first body, it is certainly consistent with this possibility, thus giving them another chance at life.

Just when the spirit enters the body is the subject of considerable interest and discussion as reviewed by Lester Bush and Jeffrey Keller.[42] Consider three scenarios: (1) the spirit enters at conception, (2) the spirit enters at birth, or (3) the spirit enters sometime between conception and birth. In the nonpredestined spirit model, if a spirit enters the embryo at conception, then clearly abortion at any time will prevent it from having a second chance to acquire a body. However, if a spirit enters at birth, abortion could result in reassignment of the spirit to another body, provided that the spirit was not predestined for the aborted fetus. The same argument can be used for any abortion, provided it occurs before the spirit enters the body. If Brigham Young is right, some spirits may have a second chance at life if they are born prematurely the first time around. This idea, however, is not consistent with the nonpredestined spirit model, if spirits are placed in the fetuses before the premature births.

There appear to be no unambiguous scriptures or statements by LDS prophets about when the spirit enters the body.[43] However, the official stand of the LDS Church on abortion allows us to infer an answer. Except for rape, incest, endangering the mother's life, or fatal defects in the fetus, the LDS Church has taken a very strong stand against abortion at any stage during fetal development.[44] Does this imply that the spirit enters the embryo at the time of conception? If so, it would suggest that, at the time spirits enter the embryo, they are very small (assuming they have a size) and that perhaps they grow along with the mortal body through its lifetime. However, if spirits enter the embryo at conception, what happens to this embryo if it is later cloned, if it fuses with another embryo, or if its genes are modified? Is the spirit also cloned or fused; and if so, are there some organisms with half spirits or multiple spirits (in the case of embryo fission or fusion)?

This scenario sounds improbable and seems to imply that spirits do not enter embryos until the embryos have developed beyond the stage that geneticists can modify them, or several weeks after conception. Also supporting this idea is the fact that 30-40 percent of human embryos are spontaneously aborted, chiefly in the first few weeks after conception. If spirits were already in these embryos, this would terminate their "life" before birth, thus discriminating against or perhaps favoring these individuals, depending on what happens to these spirits after death. In any case, unless they are recycled into another body, they are deprived of an earthly life.

Organic Evolution