Transgender

Introduction

Welcome to the Dialogue Journal’s curated page on transgender topics. Our collection of articles, essays, and personal narratives aims to promote dialogue, education, and understanding surrounding the transgender community. Transgender identities are multifaceted, spanning a range of gender expressions and experiences. These entries help to foster understanding and challenge stereotypes and misconceptions surrounding transgender identities.

To celebrate Pride Month, Dialogue Out Loud presents this special panel discussion with authors who have written about trans Mormon issues in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. Journal Editor Taylor Petrey sits down with Emily English, Ray Nielson, and Keith Burns to explore their experiences and research into this important topic at a time when trans voices are facing prejudice and discrimination across the country.

Transcending Mormonism: Transgender Experiences in the LDS Church

Keith Burns and Linwood J. Lewis

Dialogue 56.1 (Spring 2023): 27–55

Enjoy an interview about this piece here.

Desiring to better understand how people are navigating these complex identity negotiations, I interviewed seven trans and/or gender nonconforming Mormons between eighteen and forty-four years old living in various regions of the United States as part of my graduate studies at Sarah Lawrence College in New York

Listen to an interview about this piece here.

In 1980, LDS authorities used the term “transsexual” for the first time publicly when they prohibited “transsexual operations” in their official General Handbook of Instructions. They made clear that “members who have undergone transsexual operations must be excommunicated” and that “after excommunication such a person is not eligible for baptism.”[1] Such harsh policies were rooted in a broader ambience of strict boundary enforcement of a male–female gender binary and patriarchal hierarchy. This gender-based power structure relied (and still relies) on biologically and theologically essential claims of sexual difference while paradoxically asserting the perpetual malleability and fluidity of gender performance and behavior.[2] In other words, LDS leaders have simultaneously framed gender as biologically immutable and a contingent product of culture, practice, and environment.[3] However, because the LDS Church among broader conservative movements was focused on the more culturally and politically salient issue of homosexuality, their mentions of trans issues remained scarce for many decades.

In the 2020 General Handbook, LDS authorities added more detail than ever before regarding trans issues.[4] Some additions seemed to show increased compassion and inclusion for trans individuals, while others doubled down on long-standing discriminatory policies that punish transitional surgeries.[5] In addition, they made clear that “social transitioning” would be grounds for membership restrictions[6] (i.e., Church discipline), a new policy that has raised questions about how boundaries of gender nonconformity will be policed in the Church. To make legible an identity (or identities) that currently has little to no semantic or symbolic space in LDS theology, many trans Mormons conscientiously negotiate the relationship between their religious and gender identities, a process that often involves conflict, pain, and despair.[7]

Desiring to better understand how people are navigating these complex identity negotiations, I interviewed seven trans and/or gender nonconforming Mormons between eighteen and forty-four years old living in various regions of the United States as part of my graduate studies at Sarah Lawrence College in New York. All participants identified as white, politically liberal, and were either current or former college students.[8] They will be referred to with pseudonyms to protect their anonymity. Six of the seven interviews were one-time hour-long conversations via Zoom, and one interview with an individual I will refer to as Juliana (age forty-four) was a written exchange that consisted of several emails. Analyses from the interviews are intermingled throughout with the purpose of highlighting some of the nuances, complexities, and differences that exist across trans Mormon experiences.

In order to present sufficient contextual background, I will first provide a brief history of gender and homosexuality in the post–World War II LDS Church. Next, I will discuss in depth the specific ways in which interviewees were negotiating and making meaning of their trans and Mormon identities in the context of broader trans experiences. I will then describe important evolution on Church policies affecting trans individuals and propose institutional and theological suggestions for creating a more inclusive and affirming space for all sexual and gender identities within the Church. Ultimately, the beauty and diversity of trans Mormon experiences calls for a restructuring of current cissexist and heterosexist Church policies and a reimagining of LDS theology such that moral character and eternal glory are not dependent on one’s gender identity and romantic relationships.

LDS Frameworks on Homosexuality and Gender—An Overview

Before delving into the specific experiences of those I interviewed, I will provide an overview of the ways in which LDS elites have constructed sexual and gender classification schemes that perpetually position non-heteronormative individuals as deficient, oppositional, and/or sinful, a sociological phenomenon referred to by Michael Schwalbe as “oppressive othering.”[9] As gay and lesbian sexual liberation movements gained increased social and political momentum in the late 1950s and 60s, LDS authorities began harshly and publicly condemning homosexuality (and then later transgender experiences) on the grounds that it confuses gender roles and fundamentally defies God’s universal plan.[10]

Homosexuality

Because experiences around what we now call “transgender” identity did not have linguistic space until the latter part of the twentieth century, the first mentions of sexual and gender minorities by LDS authorities focused on people they referred to as “homosexuals.” In fact, the first time the words “homosexual” and “homosexuality” appeared in a public speech from an LDS authority was in 1952.[11] Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, Church leaders had begun punishing alleged “sodomites,” excommunicating members found guilty of “the crime against nature.” They even organized “witch hunts,” where Church officials hunted down and interrogated allegedly homosexual men, enacting harsh disciplinary action upon guilty individuals.[12]

Rhetoric from Church elites around homosexuality became increasingly harsh and public during the 1950s and 60s.[13] Spencer W. Kimball, a prominent mid-twentieth century figure in Mormon leadership, after discovering that several Christian groups had started reaching out in compassion to homosexuals, stated: “Voices must cry out against them. Ours cannot remain silent. To the great Moses, these perversions were an abomination and a defilement worthy of death. To Paul, it was unnatural, unmanly, ungodly, and a dishonorable passion of an adulterous nature and would close all doors to the kingdom.”[14] His stern condemnations were part of a top-down campaign in which LDS leaders framed homosexuality as a viral contagion and serious threat to individual, familial, and societal well-being, one that required urgent treatment and forceful eradication.[15] In line with white, middle-class notions of respectability, Mormon leaders frequently positioned homosexuality as part of the decaying moral fabric of American society and antithetical to happy, successful family life. In doing so, they leveraged a host of “homosexuality causes” that often had to do with poor parenting, sexual abuse, masturbation, pornography, and a confusion of gender roles, among other things.[16]

Exposure to pornography was an especially prevalent explanation. For example, LDS authority Victor Brown once said to a worldwide church audience: “A normal twelve- or thirteen-year-old boy or girl exposed to pornographic literature could develop into a homosexual. You can take healthy boys or girls and by exposing them to abnormalities virtually crystallize and settle their habits.”[17] Echoing traditional Christian fears concerning pornography, as well as middle-class fears about sexual knowledge and experimentation,[18] LDS elites argued that moral transgressions like pornography could literally cause homosexuality. These oppressive frameworks, grounded in psychodynamic theories of sexual malleability and fluidity, paved the way for the widespread practice of aversion therapy and reparative therapy (reparative therapy is sometimes referred to as conversion therapy).

The general assumption of Church leaders at the time was that sexual malleability explained “how someone could . . . become homosexual to begin with” and offered “a plan for that person to embrace heterosexuality.”[19] Aversion therapy, most notably practiced at Brigham Young University at least until the late 1970s, may have consisted of electroshock therapy programs, nausea-inducing chemical treatments, and a host of other dehumanizing methods in an attempt to change the sexual orientation of homosexual people.[20] Reparative therapy and other less aggressive forms of sexual orientation change efforts have persisted for many more decades and are even still practiced today.[21] Under the guise of healing and helping homosexual individuals “overcome their disease”[22] through a variety of treatment methods, the LDS Church justified decades of inhumane and sometimes torturous methods in an attempt to obliterate homosexuality from the Church and American society as a whole.

Gender

Central to LDS theology is the idea that gender is an essential and divine characteristic assigned by God in the premortal life. In a semi-canonical 1995 document called “The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” top LDS leaders declare that “gender is an essential characteristic of individual premortal, mortal, and eternal identity and purpose.”[23] They also explicitly outline what they believe to be God-given male and female roles: “By divine design, fathers are to preside over their families in love and righteousness and are responsible to provide the necessities of life and protection for their families. Mothers are primarily responsible for the nurture of their children.”[24] Within this patriarchal framework, LDS leaders have grounded female domestic labor and male economic opportunity in appeals to a “divine order.”

This institutional structure is an example of what Raewyn Connell refers to as a “gender regime,” or a particular configuration of power relations based on gendered divisions. She further explains that the construction and maintenance of patriarchal regimes often utilizes “strategic essentialism,” or explanations of origin regarding supposedly innate sexual differences.[25] She concludes that “most origin stories are not history but mythmaking, which serves to justify some political view in the present.”[26]

Although modern LDS leaders on the surface have presented gender as an immutable characteristic that begins in premortal existence, they have also devoted tremendous effort and resources to regulating male and female gender roles through political, legal, and cultural norms.[27] On the one hand, they have claimed that male and female sexual differences are natural and self-evident, but on the other hand, they have provided tireless cautions regarding the perpetual malleability and contingency of gender performance.[28] In other words, if not policed through institutional and cultural norms, gender identity and performativity is always at risk of failure, confusion, or alteration—a phenomenon that has at times been implicated as a cause (and a result) of homosexuality.[29]

Notwithstanding such contradictions, LDS gender schemes have long supported patriarchal frameworks that domesticate and subordinate women while empowering and enriching men.[30] More egalitarian notions of marriage have entered into LDS teachings in recent decades, something Taylor Petrey refers to as “soft egalitarianism,” because men still “preside” over the home and the Church.[31] And since there is such a strong emphasis on conformity and obedience in the LDS Church, many male and female members who internalize these notions of sexual difference and mid-twentieth-century gendered divisions of labor tend to feel close to God and fortified in their faith.[32]

Along with the emergence of rhetoric targeting homosexuality in the 1950s, Church leaders began describing gender as completely interchangeable with biological sex. LDS authorities (perhaps until very recently[33]) have collapsed gender and biological sex into one concept, an ideology that defies well-accepted feminist and anthropological arguments that have distinguished biological sex (meaning male and female bodies) from socially constructed “gender” (meaning social roles and norms that vary dramatically across culture and time).[34] As a result, LDS leaders tend to view gender (including gender identity, expression, and roles) as an immutable and natural outgrowth of biological sex. Similarly, heterosexual attraction/desire is assumed to be a predetermined, innate characteristic of one’s gender or biological sex.[35] Within this scheme of biological essentialism, one that indistinguishably entangles gender and sex, Church leaders have conceptualized homosexuality as a direct result (and a cause) of gender confusion, or a concept nineteenth-century psychologists referred to as “gender inversion.” Spencer W. Kimball put it this way:

Every form of homosexuality is sin . . . Some people are ignorant or vicious and apparently attempting to destroy the concept of masculinity and femininity. More and more girls dress, groom, and act like men. More and more men dress, groom, and act like women. The high purposes of life are damaged and destroyed by the growing unisex theory. God made man in his own image, male and female made he them. With relatively few accidents of nature, we are born male or female. The Lord knew best. Certainly, men and women who would change their sex status will answer to their Maker.[36]

These arguments, which persist in the Church today, rely upon stereotypical depictions of atypically gendered homosexuality and reinforce cultural notions conflating sex, gender, and sexualities.[37] They also rely on assumptions that homosexuality both leads to and results from an “attack” on gender roles, and this rhetoric is part of a broader effort to enforce gender norms and punish gender deviance. Interestingly, Kimball’s language equates homosexual experiences with what we would now call transgender experiences when he refers to homosexuals as people who “change their sex status.” As a result, trans and gay experiences have often been rendered in LDS teachings as “the same” because they both involve a rejection of “divine gender norms.”[38] Not only does this ignore the multitude of gender identities that span gay/lesbian experiences, and the fact that many trans people do not identify as gay/lesbian, it also serves a broader goal of reducing and making illegible sexual minority experiences in LDS contexts.

The Complexities of Trans and Gender Nonconforming Experiences

Throughout my interviews, I quickly noticed that individuals construct what it means to be “trans” very differently. For trans people more broadly, ideas about gender identity, gender expression, coming out (and being out), and the concept of gender itself vary dramatically and sometimes contradict one another.[39] As I portray the personal ways in which interviewees negotiate (and renegotiate) their religious and gender identities, I will simultaneously emphasize the vast diversity contained in the space we call “trans Mormon.”

Juliana’s “Tinted Phone Booth” Analogy

Have you ever had an opportunity to go inside of a tinted phone booth? I remember going inside one of these, and when the door was closed, how small and confining it felt to be inside there. I think of this as something like what it’s like as I try to live inside my body. Being inside my body feels like my skin is like an outside wall of a phone booth and yet the “phone booth” is tinted such that not very many people can see that anyone is inside it. This is how I feel in my body. This is how I feel about my body. My female spirit inside my body yearns to be free. She pushes up against my skin and calls/pleads for help. A few people can hear her calling for help . . . and many cannot.[40]

The tinted phone booth analogy was one of the first descriptions Juliana provided about what her life was like as a “female spirit” trapped inside of a male body. This analogy seemed to capture her experiences so powerfully. She does not consider herself “out” and goes by “Julian” at work, at home, at church, and with her friends. She can count on one hand the people in her life who know about her internal sense of femaleness. Like many other trans Mormons, Juliana must navigate a series of complex, sensitive, and often painful decisions around who she is and who she wishes to be.

Gender Binary Versus Gender-free

Out of the individuals I interviewed, Juliana’s description of being a woman trapped in a male body is perhaps the most familiar and conventional when discussing trans experiences. It is important to note that she was the only middle-aged individual (age forty-four) with whom I spoke, as all others were between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five. While a significant percentage of people from younger generations do in fact experience their transness in the context of the male–female gender binary, when compared to older generations, it is more common for millennial and Gen Z trans individuals to construct gender identities that subvert or exist outside of the gender binary. Similarly, those of younger generations statistically have an easier time being out about their trans identity, while those of older generations like Juliana are more likely to remain stealth (i.e., hidden) about their trans identity.[41] These generational differences are understandable considering the substantively different cultural and political climates of current and past generations regarding acceptance of non-cisgender identities.

The individuals I spoke with revealed intricate and thoughtful ways in which they were constructing a sense of what it means to be trans and Mormon, and particularly, how they felt about gender itself as a concept. Several conceptualized their trans identity as existing within the male–female gender binary, while others described their gender identity as existing outside of or in between the gender binary. For instance, in explaining her fervent wish to allow her female spirit to be free, Juliana said:

While my name is Julian, my heart wishes so acutely it were Juliana. I try hard to attend and participate in elders quorum [church group designated for men]. My heart wishes, however, that I could be in Relief Society [church group designated for women]. I try to bear numbing internal frustration, in part from a feeling like I need to wear a white, button-up shirt and necktie, by wearing mainly ties that have some pink in them; though my heart yearns to be wearing, instead, a cute dress and a necklace. But it’s so much more than clothes. It’s also sisterly connection.[42]

As demonstrated by this moving excerpt, a sense of being trans for Juliana is inextricably linked to the male–female gender binary. Her sense of self is not only built on the feeling of “being female” but also on deeply yearning to “do female things,” such as attending Relief Society meetings, having pink in her ties, and wearing “a cute dress and necklace.” However, she explains that it is more than simply outward expression and clothing choice. She longs for a “sisterly connection” that would come from surrounding herself with other women.

Sarah (age twenty-three) was assigned male at birth and also experiences her trans identity within the gender binary. She underwent a gender confirmation surgery, transitioning to a woman in 2019. Interestingly, when asked about the concept of gender, she affirmed the LDS Church’s conservative stance that God created two eternal genders—male and female. Thus, she simply believes that God gave her the wrong body: “While I don’t have all the answers about gender, I at least know that God created male and female in his image. As for me and my situation, I don’t exactly know what happened, although I do believe that God made me female and for some reason put me in a male body.”[43] Sarah’s belief that God mistakenly clothed her female spirit in a male body does not disrupt the firmness of her convictions in Mormon theology—in fact, it harmoniously fits within her beliefs about the eternal and essential nature of gender.

Kevin (age twenty-two) identities as a member of the trans community and more specifically as bigender. They described the complexity of their gender identity in this way:

As I got older, I would talk to women, and I wished I was them. And in my sexual fantasies, I found myself, like, desiring to be a woman sometimes. And so recently, I’ve realized, like, that there’s some aspects of being male that I feel I identify with and desire. And then there’s also some aspects of being female that I empathize with and desire. I know a lot of trans people who kind of feel sort of in the middle where they just don’t really feel like they fit in with either. I’ve heard people describe themselves as, like, genderless blobs, and things like that. But that’s never how I’ve felt. I’ve felt more like both genders and like strong pulls to either, instead of, like, being pushed towards the middle. So that’s kind of why I’ve stuck with the bigender label, because it seems to fit that the best.[44]

Unlike Juliana, Kevin feels pulled toward both male and female genders, and their desire to be masculine and/or feminine varies across context and space. In this way, the term “bigender” provides clarity for their experiences and stands in contrast to what Kevin calls a “genderless blob.”

Emily (age twenty-two) describes their gender identity as existing outside of, or perhaps in between, male and female concepts. They explained:

The more that I kind of read about different connections to, like, gender and gender identity, I just kind of realized that I don’t strongly identify or, like, feel really tied to being a girl or boy. Like, sometimes I used to have my hair all pulled up. I used to pull it up a lot, just like in a hat and hide it. And I would get, like, mistaken for a boy. And that, like, didn’t bug me. But it didn’t particularly make me feel, like, super awesome either. It was just like, okay, like, it just didn’t matter. And so I’ve been having a lot more friends that are trans or nonbinary. And I kind of was just like, “Oh, I mean, yeah, that’s how I feel. I didn’t know that.” So, I’m still trying to put words to it. And it’s weird because it doesn’t feel like I necessarily need to change how I look or how people refer to me. Um, but inside myself, I feel like I identify as nonbinary, like, not as strictly a boy or girl.[45]

Emily describes more of a neutrality or even apathy about their gender expression. Being “mistaken for a boy” was neither good nor bad for their self-image. In fact, they further explained that they “don’t feel much of a need to label” themselves at all.

Beth (age eighteen) believes that God is not limited by a gender binary and encompasses a broad spectrum of gender identities.

I absolutely know that nothing about me is a mistake. I absolutely know that people can change and people are capable of love. And I absolutely know that the divine, however you want to see that, however you want to see that divinity, cannot be limited and should not be limited when it comes to gender identity. God is not limited to male or female. Because the divine is all-encompassing. It’s an all-encompassing love and an all-encompassing power that you can sit with and you can adapt to yourself however you want and that you can find strength in.[46]

Many trans Mormons like Beth validate their gender identity with appeals to a benevolent God who “doesn’t make mistakes.”[47] As someone whose gender identity falls outside of the traditional binary, Beth articulately affirms that God is the author and creator of all types of gender identities and experiences. Embedded in this position is a view that God’s concept of gender (or lack thereof) has been tainted by sociohistorical and political constructions that have been organized into limiting male–female gender schemas.[48] Thus, some trans Mormons subvert altogether the Church’s teachings regarding gender, while others explain their experiences within an “eternal gender” framework.[49] This reflects broader attitudes within United States trans communities, where there are some who advocate for an abolition of gender altogether, and yet others who call for an assimilation of nonconforming gender identities into previously existing gender structures.[50] As with Beth and Kevin, many individuals who resist or avoid the male–female binary still use the umbrella term “trans” to describe their identity while also using terms like genderqueer, gender nonbinary, bigender, gender-free, and/or agender to provide added or more specific meaning.[51] However, some gender-variant individuals prefer not to use the term “trans” at all, a phenomenon that further complexifies the usage of these terms and the symbolic and semantic spaces they occupy (or do not occupy).

Sexual Identity

Several individuals were in committed romantic relationships at the time of interview, including Sarah, who described the difficulty of articulating her sexual identity several times during our exchange. At one point, she explained that her relationship to her trans boyfriend puts her in an ambiguous space when it comes to sexual identity: “To be honest, I am not really sure about what my sexual identity is. Most of the time, I just identify as straight because I’m dating a trans guy, but I sometimes ask myself, am I pan? Or maybe bi?”[52] While Sarah’s curiosity and uncertainty regarding her sexual identity was notable, she did not appear concerned about her difficulty describing it.

Like Sarah, Theresa (age twenty-five), who identities as nonbinary, also finds themselves in a space of ambiguity when it comes to sexual identity. They explained: “And then there have been brief phases where I was like, do I like guys? Do I not like guys? Am I just a lesbian who’s confused? And especially in a society like ours—and I don’t mean just LDS culture, I mean just heteronormative culture in general—it can be very confusing to be sure of what your identity is.”[53] Acknowledging the difficulty of defining their sexual identity, Theresa points out heteronormative cultural pressures that influence the process of identity development and the labels they decide to adopt. It is particularly interesting that they wonder if they are a “lesbian who’s confused,” a common cultural and theological notion that has framed transgender experiences as a hyperextension, an extremized version, or “the final result” of homosexuality.[54] Indeed, both Sarah’s and Theresa’s difficulties in expressing their sexual identities reveal the complex conceptual interplay between gender and sexuality. Their descriptions demonstrate that experiences of sexual desire and identity are dependent upon an ongoing appraisal of one’s own and one’s partner’s gender identity, a phenomenon that reveals the overlapping fluidity and contingency embedded in such categories.[55]

Coming Out Versus Being Out

The individuals I interviewed characterized the concepts of coming out and being out with complexity and variation. For Juliana, who is not public about her trans identity, coming out has been a deeply private process involving careful decisions about when, and with whom, to disclose identity. To bring in again her tinted phone booth analogy, she yearns to remove the tint on the windows or restructure the windows altogether, although she feels she has no choice but to remain “trapped” inside. She explained: “I am nervous to share this secret. What would I do if people no longer accepted me in my current job, or if my children got hurt or shamed? These things worry me terribly. I’m not ready to share this with everyone yet, though sometimes I think many might already know or maybe have put two and two together.”[56] Juliana feels that her familial, social, and professional life would crumble if her gender identity were made public. Interestingly, she presents herself in normatively masculine ways (i.e., wears men’s clothes, uses typical masculine mannerisms), but she still fears that others may be suspicious about her “secret.” I imagine that this hypersensitivity is common among trans Mormons who are not out, an indication of the immense fear and anxiety people like Juliana experience at the thought of others finding out about their identity.

For others, a physical and/or social transition is in and of itself a type of coming-out, or as many trans individuals put it, “being out.”[57] When several individuals I interviewed explained the concept of “being out,” they emphasized that they are not necessarily out by choice. Their altered physical appearances, either because of surgery, hormonal treatment, and/or gender expression, create a constant state of “outness,” one in which their personal decisions around when and with whom to disclose their gender identity become less relevant. Beth described her sense of being out in this way:

I was just out running errands for somebody one time, and I was standing at a tech store, and my back was facing the door and somebody came in. And one of the sales associates was like, “Oh, I’ll be right with you.” And the guy was like, “Oh no worries, he was there first.” And I was like, whoa. I couldn’t stop smiling. I was like, I can’t believe that I was perceived as slightly androgynous. So, I don’t experience gender dysphoria, as much as I do experience gender euphoria, you know, able to present and be perceived as, you know, androgynous, even though nonbinary and androgynous aren’t necessarily equal, but you know, it just makes me feel very happy.[58]

Even though Beth identifies as nonbinary, they frequently explained a desire to be “perceived as androgynous.” This experience of being read as a “he” in the store shows that Beth’s sense of being out is less about verbalizing or declaring their gender identity and more about being perceived in certain ways by others. They describe a feeling of “gender euphoria” as opposed to dysphoria when others are able to correctly perceive their expression of gender in a particular context.

Identity Salience

For some, identifying as trans is a crucial and all-encompassing part of their sense of self, while for others, it takes up a small or nonexistent identity space.[59] Several of the trans Mormons I spoke with reflected this broader phenomenon, as they articulated the salience of their transness (or lack of transness) in significantly different and complex ways. To provide a few examples, Emily, who identifies as nonbinary, explained their gender identity in this way:

About a year ago is when I kind of started to question my gender. And it’s kind of weird, because, like, I feel comfortable kind of presenting pretty feminine sometimes, like I have my nails done and, like, long hair and I still go by Emily. But sometimes, I feel comfortable presenting more masculine, like with my hair rolled up. Sometimes people will, like, automatically think that I am trans because I prefer to use they/them pronouns and present in, like, ambiguous ways, but I don’t think of myself as trans because I don’t really have a desire to transition to any specific gender identity.[60]

For Emily, a nonbinary identity is not connected to a trans label. They do not consider themselves to be trans because they lack the desire to “transition” to a specific gender identity, a notion that links trans identity to the traditional gender binary.

Kevin, on the other hand, uses the term “trans” as a way to explain their bigender identity:

I’m still kind of figuring out my gender. But the one [term] that has stuck with me the most right now is bigender. It’s a label that’s under the trans umbrella. And I definitely feel comfortable in the trans community. But yeah, I, like, found that a lot of the people I was closest to and had the most similar case to in my online friends community were often trans. And I found that a lot of the music I liked was the same frequently as people who are trans and I felt connected to the emotions and identity of the music and the themes it was exploring.[61]

Although Kevin describes their identity in tentative terms, they express a comfortability and resonance with the “trans community.” Interestingly, their sense of transness is also connected to the particular emotions and identity of their music preferences, which they have found to be shared by other trans people. It seems that a significant aspect of Kevin’s trans identity is the social comradery and connection that comes from their intimate social circles consisting of other trans individuals. Kevin’s and Emily’s intricate articulations of their gender identities demonstrate the varying levels of salience that gender nonconforming individuals may or may not assign to the term “trans” when making sense of their identities.

Gender Dysphoria

It is commonly assumed that trans identity is inseparably connected to an experience of gender dysphoria. However, several individuals I spoke with did not report any feelings of gender dysphoria. Recall that Beth describes a feeling of “gender euphoria” as opposed to gender dysphoria. They elaborated on that concept in this way:

I had this dream one time that I was performing in, like, a drag king sort of setting. And I was perceived as super butch and masculine and that sort of stuff. And then as the song progressed, I transformed into a more and more feminine version of myself. And when I woke up from that dream, I was like, that’s the most whole I’ve felt in my entire life, is when I can accept both of those ends of the spectrum in myself, and I can see all of those complexities and nuances in myself. So, once I started to be a little more aware about that, when people use gender-neutral pronouns for me, or anything like that, it’s just this sense of like, yes, that is who I am![62]

Beth’s gender identity involves an embracing and harmonizing of masculine and feminine concepts. Rather than experiencing a sense of dysphoria or conflict, Beth feels affirmed and “whole” when they embrace “both ends of the spectrum” in themselves. They went on to explain that their experience of feeling more masculine or feminine depends on the time and context and can often feel unpredictable.

Unlike Beth, Juliana has been diagnosed with gender dysphoria by a previous mental health clinician. She explained:

Looking in mirrors is painful for me because a reflection looking back at me doesn’t match who I see myself as on the inside. Not a day goes by that I’m not reminded of this. Thirteen years ago, when my depression reached a point where I was struggling to sleep, I decided to go see a therapist. I explained to this therapist that I’d been waking up in the middle of the night (my sleep would just thin out and I would find myself staring at the ceiling at two o’clock in the morning), just wishing/yearning that I could put on a dress. Often my pillow was wet with tears. After a few months, the therapist diagnosed me with gender identity disorder—a designation that was eventually changed to gender dysphoria.[63]

Juliana experiences immense distress over the painful and incessant dissonance between her assigned biological sex and her internal sense of gender. However, because of social and ecclesiastical fears, she does not feel that transitioning is a reasonable possibility at this point in her life.

From a clinical perspective, gender dysphoria is diagnosed when one experiences significant levels of distress and/or dysfunction, such as Juliana’s experiences described above. Furthermore, having a gender dysphoria diagnosis is often a prerequisite for receiving insurance coverage for gender confirmation surgery and/or hormonal treatment, a structural reality that often leads clinicians to overdiagnose gender dysphoria.[64] Clinicians and researchers continue to discuss complex questions regarding the so-called “etiology” of gender dysphoria. Is one’s sense of dysphoria caused by an inherent physiological-psychological disconnect between assigned biological sex and internal sense of gender, or rather by a culturally constructed system that discriminates against and ostracizes gender-nonconforming individuals? Or a combination of both?[65] Examining these challenging questions helps researchers and clinicians to better appreciate the complex, mutually constitutive interplay that occurs between individual experiences and cultural scripts regarding gender.

Battles over Labels

The specific language gender-nonconforming Mormons use to describe themselves intersects with complex sociocultural and religious factors, including the fact that LDS leaders have for decades sought to regulate the ways in which others conceptualize their experience of gender.[66] They have often discouraged the use of what they view as “permanent” or “fixed” labels in favor of descriptors that signify a temporary and resolvable condition or trial.[67] For example, the label “same-sex attracted” was for decades preferred over gay, lesbian, or queer.68 Only recently has this begun to shift, as the majority of current leaders have become increasingly accepting of the term “transgender” as an identity label.[68]

Another powerful rhetorical technique has been the framing of gender-nonconforming experiences as the result of confusion caused by Satan. Boyd K. Packer said in 1978: “If an individual becomes trapped somewhere between masculinity and femininity, he can be captive of the adversary and under the threat of losing his potential godhood.”[69] For Packer, Satan’s traps lay deceptively between the rigid boundaries of a Victorian gender binary, and if an individual was failing to perform gender “correctly,” they were at risk of losing salvation and godhood. In a more recent speech addressing the worldwide Church, Dallin H. Oaks said: “Our knowledge of God’s revealed plan of salvation requires us to oppose current social and legal pressures to retreat from traditional marriage and to make changes that confuse or alter gender or homogenize the differences between men and women. . . . [Satan] seeks to confuse gender, to distort marriage, and to discourage childbearing—especially by parents who will raise children in truth.”[70]

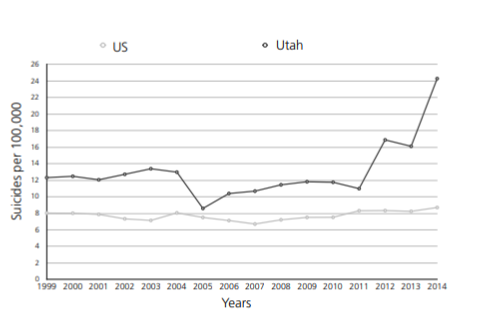

Both outspoken and prominent voices on issues of gender and sexuality, Packer (who passed away in 2015) and Oaks have frequently invoked God’s authority to shore up heteronormative cisgender claims, a tactic that simultaneously adds credibility and force to their assertions while also deflecting responsibility from themselves and other Church leaders, the very individuals who have the power to change policies and teachings regarding sexual and gender minorities.[71] In addition, describing Satan as the author of “confusion” around sexual and gender variation is a weaponizing technique that can exacerbate internal shame, depression, and suicidality among LGBTQ+ Mormons.[72] The employment of the figure “Satan” has also contributed to the long-standing framework that cisgender heterosexual identities and relationships are “real” while non-heteronormative identities and relationships are “counterfeit.”[73] In 2015, senior leader L. Tom Perry explained: “We want our voice to be heard against all of the counterfeit and alternative lifestyles that try to replace the family organization that God Himself established.”[74]

These types of top-down messages and battles over language can sometimes discourage Church members from adopting an identity label under the trans umbrella by framing heteronormative cisgender experience as the only possibility allowed by God. Among those influenced by this rhetoric is Mary (age twenty).

And then in terms of gender, this is something I haven’t talked about much with my parents, but I have a friend whose boyfriend is transgender. And my parents have equated it to kind of like, sometimes there’s people who will have a ghost limb, even though their arm is still there, they’ll feel like, Oh, my arm isn’t supposed to be there or something. And my dad would say like, “Oh, even though they have this feeling that this part of their body is wrong, like, a doctor is not going to just cut off their arm because that would harm the person.” And they kind of equate that to, like, gender reassignment surgery, it’s kind of like, even though you feel this way, like, that’s just not the way that things are. So yeah, I think in terms of my family, it’s kind of just like, oh, here are the standard norms set by our family and our religion. And like I said before, how my dad compared it to his friend who cheated on his wife, or also in previous letters he has said, like, he doesn’t want me to use trans as a label, that he would prefer that I use labels like, oh, I’m a child of God, like that’s my primary label.[75]

Having grown up in an environment where transgender experiences were equated to having a phantom limb or cheating on a spouse (a disorder and an immoral behavior), Mary finds it difficult to label their current experiences pertaining to gender. They point out the powerful influence family and religious norms have had on their identity formation, especially their dad’s discouragement of the use of “trans” as a label. Recently, Mary has been “experimenting with [their] pronouns” and considering a “nonbinary” identity label. However, “child of God” as the “most important label” is an idea that has been deployed by LDS leaders who have sought to minimize or erase non-heteronormative identities.[76] Thus, it is crucial that gender-nonconforming Mormons critically analyze top-down messaging regarding labels as they construct a sense of identity in ways that feel most meaningful to them.

A Crucial Ternary for Trans Mormons

LDS gender minorities often navigate complex paths of identity negotiation and formation. While many feel they must make an “either-or” choice between their religious and gender identities, others find (or place) themselves in more ambiguous territory, negotiating a working relationship between these identities.[77] In a 2015 survey of 114 trans Mormons (or former Mormons), 38 percent of respondents said they were on LDS membership rolls and identified as LDS, 43 percent thought their names remained on the rolls although they themselves no longer identified as LDS, and 19 percent said they were no longer members of record.[78] As these results depict, a vast diversity of trans Mormon experience exists, as individuals conceptualize (and reconceptualize) a dynamic and ongoing relationship with God, the Church, and themselves. Below is an illustration of this three-part relationship, or what I refer to as “a crucial ternary for trans Mormons.”[79]

As part of this ternary, the trans Mormons I interviewed were each uniquely negotiating a relationship between their personal experiences, their religious convictions, and their institutional loyalties to the Church. For Sarah, remaining faithful to the Church is pivotal to her sense of self and does not detract from her trans identity. She explained:

I’ve been reading a lot of stuff online from other trans Mormons—or I guess I should say ex-Mormons. A lot of people say something along the lines of “you’re rejecting your trans identity if you stay in the LDS Church.” I really don’t agree with that. I feel like I am a trans woman through and through. While I do have very real fears about even the thought of transitioning, I don’t feel like that detracts from my overall sense of identity. I don’t think people should be so judgmental about what people should or shouldn’t do. Decisions around transgender identity should be left up to the individual.[80]

This sentiment that only by leaving the Church can one fully embrace their gender identity is commonly expressed among trans former members of the Church.[81] However, Sarah, who is deeply connected to her LDS identity, feels that this type of advice fails to acknowledge the personal complexities and individual nature of trans Mormon experiences. Furthermore, such notions create classification schemes that label people as “more” or “less” trans, a framework that often leads to judgment, divisiveness, and misunderstanding.

While several individuals I spoke with had completely disaffiliated from the Church, others were critical about some Church teachings while still describing themselves as faithful members. For example, Emily explained their relationship with the LDS Church in this way:

It’s okay if I don’t go to church one week. And it’s okay to not believe every single thing. Once I decided that, I felt a lot more free to, like, figure out what I actually liked about the Church or how I actually felt and who I was. Because I think that the Church’s structure, as presented to me at least, was very rigid. And so, those problems that came up, I didn’t know what to do with. And so once I was like, oh, that’s okay, I can just choose the things that I like, I felt a lot more like I started discovering my identity, if that makes sense.[82]

Emily grew up in an environment where they felt they needed to accept every teaching and claim of the Church. In recent years, they have embraced a more selective approach, choosing to accept or reject Church teachings according to their personal judgment and experiences. They emphasize what they see as the “beauties” of “the Church” and “the gospel,” while simultaneously expressing skepticism toward teachings they deem as more a product of “human imperfections.” This approach is captured by a long-standing label found in LDS culture (and other faith traditions): “cafeteria Mormon,” i.e., a Church member who accepts teachings they agree with and rejects teachings they do not agree with.[83] Several individuals I interviewed described their relationship to the Church in this way. Kevin, for example, wished they would have adopted a “cafeteria Mormon” approach earlier in life. They explained:

And it’s kind of sad, because I have a lot of friends that are still in the Church but are dating somebody of the same gender. And they’re like, “Oh, well, I just feel like I have a really close relationship with God, and so I know that this is fine for me.” And they’re like, “You can have that too.” And it just feels too late, if that makes sense. Which makes me sad, because I feel like if I grew up feeling like I could have part of it, and I don’t have to believe in every single rigid thing, then I would have been able to stay and have that church community. And have the comfort of going to church and feeling like I have heavenly parents who love me and Jesus to be on my side. But now it kind of feels like it’s too late.[84]

Kevin finds great value in the sense of community facilitated by the Church as well as the core teaching that heavenly parents love and want to help their children, although they feel that it is “too late” to repair the years of damage and trauma caused by their Church membership. Kevin certainly feels like such harm could have been alleviated by a more nuanced and less “rigid” approach to faith, one in which it was okay to accept some teachings and reject others. This type of “pick and choose” mindset that Kevin is describing seems to provide a safer space whereby some trans members can find a home in the Church.

Another idea expressed by several interviewees is that their personal relationship with God transcends or supersedes their relationship with the Church. In the same survey of 114 trans Mormons that I referenced previously, 86 percent of respondents placed more importance on personal revelation than on obedience to Church authority in their religious lives.[85] A theological foundation of Mormonism is that God hears and answers prayers and will give personalized revelation and inspiration to those who seek it.[86] However, the idea that God answers individual prayers and gives specific direction accordingly poses an uncomfortable tension and paradox in LDS theology. On the one hand, individuals are encouraged and even expected to seek answers from God regarding important decisions in their life; on the other hand, conformity and obedience to leaders is paramount to LDS constructions of faithfulness and devotion.[87] So, what happens when one’s personal revelations from God do not align with what Church leaders are teaching to be God’s word? Several trans Mormons I spoke with were asking (or answering) some version of this question. Here is Beth’s thoughtful perspective:

Another thing that is preached so heavily in the LDS Church is that once you leave, you will never find happiness. And that is so untrue. You can find the same spirituality and divinity and happiness in other places because that is inside of you, and not anything that an organization or an institution gives to you. And that was a real turning point for me recognizing that I could still hold to my faith and stand up for equality, and stand up against the institution of the Church. And that’s really I think the phase we’re in right now of understanding that institutions don’t always have all the answers, and that doesn’t make your faith or answers to prayer any less valid or any less sacred.[88]

Prior to this turning point in thinking, Beth grew up in an environment where LDS leaders were given final authority to determine the decisions and behaviors that constitute “true happiness.” They no longer grant that authority to religious institutions and organizations (especially the LDS Church) and instead place moral authority on their own sense of judgment. As they point out, divinity and spirituality are internally discovered and personally governed pursuits, not absolute truths dictated and regulated by religious authorities. In short, Beth privileges their personal judgment and inclinations over the moral and theological assertions of Church leaders.

Institutional Evolution on Trans Issues

LDS leaders periodically revise what is now called the General Handbook, a manual that contains detailed instructions about Church procedure, policy, and doctrine.[89] The first ever mention of the word “transsexual” appeared in the 1980 version of the handbook, where there was a small and somewhat vague section regarding “transsexual operations”: “The Church counsels against transsexual operations, and members who undergo such procedures require disciplinary action. . . . Investigators [prospective members learning about the Church] who have already undergone transsexual operations may be baptized if otherwise worthy on condition that an appropriate notation be made on the membership record so as to preclude such individuals from either receiving the priesthood or temple recommends. . . . Members who have undergone transsexual operations must be excommunicated. After excommunication such a person is not eligible for baptism.”[90] The addition of this section in the general Church handbook was possibly in response to a specific and unusual case involving a Church member who had undergone a male-to-female surgery and desired a temple marriage with a cisgender male. Uncertain about how to proceed, her stake president contacted the presiding General Authority, Hugh Pinnock, who authorized the individual to receive her temple endowment and get sealed to her husband as a woman (their temple wedding was performed in February of 1980). Shocked and surprised by Pinnock’s authorization, the stake president contacted another General Authority, Robert Simpson, who emphatically repudiated what had been authorized by Pinnock.[91]

Five years later, Church leaders slightly softened their hard-line policy about “transsexual operations.” Instead of condemning a person who underwent a transsexual operation to a non-negotiable and final excommunication, there was a subtle change in policy: “After excommunication, such a person is not eligible for baptism unless approved by the First Presidency.”[92] This caveat, while still harsh, allowed for exceptions to be made and individual circumstances to be considered by the highest governing body of the Church. In 1989, language in the general handbook was again softened and revised: “Church leaders counsel against elective transsexual operations. A bishop [leader of a local congregation] should inform a member contemplating such an operation of this counsel and should advise the member that the operation may be cause for formal Church discipline. In questionable cases, a bishop should obtain the counsel of the First Presidency.”[93] It is noteworthy that Church leaders introduced the term “elective” to qualify the description of an operation, although it is still not exactly clear what they meant by it. Also, they downgraded the severity and certainty of punishment by stating that “the operation may be cause for formal Church discipline.”[94]

For the next several decades, the Church did not make substantive changes or revisions to this wording. The 2010 handbook used quite similar language with a few minor modifications: “The Church counsels against elective transsexual operations. If a member is contemplating such an operation, a presiding officer informs him of this counsel and advises him that the operation may be cause for formal Church discipline. Bishops refer questions on specific cases to the stake president. The stake president may direct questions to the Office of the First Presidency if necessary.”[95] It is interesting that the pronoun used in this section is “him,” suggesting that LDS leaders were either more concerned with transwomen (i.e., biologically assigned males who become women) or subscribing to an incorrect assumption that gender confirmation surgeries were disproportionately being performed on biological males. The former seems more plausible than the latter because violations of masculinity pose greater social and institutional threats to the Church than violations of femininity.[96] In other words, because men occupy most leadership and administrative positions in the Church, and are generally perceived as more consequential than women, “losing a man” is worse than “losing a woman.” However, it is worth noting that trans men who attend elders quorum instead of Relief Society may also threaten the ecclesiastical and social order because of their “unholy” ambitions to receive and exercise the priesthood.

One reason that this was the only statement in the 2010 handbook addressing trans issues might be that Church leaders were exhausting more efforts and resources on addressing lesbian/gay issues, especially considering their political and legal efforts to fight against same-sex marriage.[97] However, they did reaffirm in explicit terms that any form of transitional surgery would be grounds for Church discipline, a punishment that bars access to LDS temples (considered the highest and holiest form of worship) and prohibits serving in leadership positions. The fact that a surgical transition (or even considering a surgical transition) compromises one’s institutional standing and access to spiritual opportunities reflects long-standing classification schemes that punish individuals who deviate from cisgender heteronormativity.

In 2020, LDS authorities added more detail regarding the experiences of trans individuals to the handbook. In a section titled “Transgender Individuals,” they began by expressing sympathy and compassion for people who experience “incongruence between their biological sex and their gender identity”: “Transgender individuals face complex challenges. Members and nonmembers who identify as transgender—and their family and friends—should be treated with sensitivity, kindness, compassion, and an abundance of Christlike love. All are welcome to attend sacrament meeting, other Sunday meetings, and social events of the Church.”[98] This beginning section reflects a clear effort to appear more tolerant of trans individuals, especially considering that the Church has attracted negative publicity in recent years regarding their treatment of sexual and gender minorities.[99] While there arguably has been increased acceptance of trans Mormons, statements like this seem to be part of a broader effort to put a kinder and gentler brand on traditional frameworks that maintain the inferiority of gender-nonconforming members.[100] This section is also found in the most recent handbook: “Church leaders counsel against elective medical or surgical intervention for the purpose of attempting to transition to the opposite gender of a person’s biological sex at birth (‘sex reassignment’). Leaders advise that taking these actions will be cause for Church membership restrictions. Leaders also counsel against social transitioning. A social transition includes changing dress or grooming, or changing a name or pronouns, to present oneself as other than his or her biological sex at birth. Leaders advise that those who socially transition will experience some Church membership restrictions for the duration of this transition.”[101]

As in the 2010 handbook, physical transition (which they refer to as “sex reassignment,” a term that many trans individuals feel withholds affirmation of one’s gender identity) is grounds for membership restrictions, including loss of temple privileges and inability to serve in leadership positions. Beth had thoughts about the handbook’s ecclesiastical sanctions:

You know, I was thinking about their recent handbook changes that came out that said individuals that had gender-affirming surgery were no longer worthy for temple recommends and stuff. And I was just laughing a little bit because, like, it’s so arrogant to think that God really did make our bodies cisgender, you know . . . God made my body the way that I am. And so, who is anybody to say that, you know, that God didn’t?[102]

Beth’s frustrations and critiques center on the arbitrary and power-based nature of LDS theological assertions concerning gender. They question why it is acceptable for LDS leaders to tell trans individuals that decisions around their bodies and/or identities are “not of God.” The use of God as an authority figure to bolster certain theological assertions has been leveraged by LDS leaders (and other religious leaders) against sexual and gender minorities for decades.[103]

Interestingly, Church leaders added that “social transitioning” and the use of hormones for the purpose of transitioning are both grounds for membership restrictions, but only “for the duration of this transition.” Several trans Mormons with whom I spoke found these statements to be vague and arbitrary, especially the concept of social transitioning. Among those was Sarah, who shared her reactions in this way:

I don’t really get what they mean by “social transitioning.” It seems kind of arbitrary and hard to measure. I mean, I sometimes enjoy wearing pink and more feminine-looking clothing. I occasionally let my hair grow out long. Does that mean I’m socially transitioning? I feel like there are many feminine men and masculine women in the Church, and it is too difficult to regulate the blurry lines between social transitioning and just wanting to present a little more like the other gender.[104]

Sarah points out how difficult it is to police one’s performance of masculinity or femininity. After all, at what point does a biologically assigned male stop presenting male? And when does a biologically assigned female no longer appear female? Does it have to do with hair length, earrings, makeup, clothing style, mannerisms, all the above? As Taylor Petrey astutely put it, “If biology was so immutable, it wouldn’t need to be ecclesiastically enforced. In spite of themselves, these new guidelines show that for Latter-day Saints, gender is what one does, not what one is or has.”[105] This keen insight exposes the ongoing contradiction in LDS thinking that gender is a biologically immutable characteristic and a social category that requires constant regulation through cultural, theological, and legal norms. In other words, “supposedly essential differences depend on cultural production.”[106]

Such arbitrary sanctions for any kind of transitioning also exacerbate what many trans Mormons call “bishop roulette,” the idea that different bishops have drastically different ways of interpreting Church policies and teachings, interpretations that are often influenced by geographic area, age, and/or political orientation.[107] What may appear as “social transitioning” to an older, more conservative bishop from rural Utah may be deemed a perfectly appropriate presentation by a younger, more progressive bishop from New York City. Due to the unpredictability of local leaders’ perspectives and approaches, many sexual and gender minority members find themselves jumping across congregations until they find a bishop that is friendlier toward them. Theresa described a telling personal example of “bishop roulette”:

And so, I ended up dating my friend who is trans. And I told my bishop that I was dating someone. And he lights up. And I say, “Just so you know, he’s trans,” and his face drops. And I basically didn’t go to the ward after that because I just, I couldn’t deal with it. I was so frustrated. Like, you’re so excited that I’m dating someone until you find out that.[108]

Understandably frustrated and hurt, Theresa tried a different congregation and found a bishop “who was much more supportive” and “happy to hear” that they were in this new relationship. Theresa pointed out that the second bishop was considerably younger than the first, highlighting what they saw as a clear generational effect. Like Theresa, many trans Mormons encounter drastically different and sometimes opposing viewpoints on Church policy and teachings from local leaders, a phenomenon that can often feel confusing, disorienting, and painful.

Although Church leaders doubled down on policies and teachings that encourage individuals to conform to their assigned biological sex, there were segments of the 2020 handbook that offered glimmers of hope for trans Mormons. While any form of transitioning is still grounds for Church discipline, a small note was added about the use of preferred pronouns: “If a member decides to change his or her preferred name or pronouns of address, the name preference may be noted in the preferred name field on the membership record. The person may be addressed by the preferred name in the ward.”[109] Many trans Mormons and advocates were pleasantly surprised after finding this apparent concession in the updated handbook.[110] However, it is important to note that the key term here is “preferred name.” While local leaders will allow individuals to be addressed by their preferred name and pronouns, they will not allow individuals to change their actual name on membership records, a distinction that continues to make clear that any form of transition away from one’s biologically assigned sex is not accepted.

Another policy addition that has been cause for hope among trans Mormons has to do with baptism and confirmation (rituals necessary for entrance into the Church) as well as temple and priesthood ordinances (sacred rituals/steps made available to “worthy” members of the Church): “Transgender persons may be baptized and confirmed as outlined in 38.2.3.14. They may also partake of the sacrament and receive priesthood blessings. However, priesthood ordination and temple ordinances are received according to biological sex at birth.”[111] Before 2020, the question of whether trans individuals could be baptized and confirmed was a thorny issue for local leaders.[112] Some felt it was acceptable while others did not. Perhaps implementing a blanket policy allowing trans people to join the Church through baptism is a step in the right direction. However, it is important to note that section 38.2.3.14 of the handbook clarifies that a trans individual who is “considering elective medical or surgical intervention for the purpose of attempting to transition to the opposite gender of his or her biological sex at birth (‘sex reassignment’) may not be baptized or confirmed.”[113] Therefore, people who have transitioned before desiring to join the Church are permitted to be baptized and confirmed, but only if they have turned away from their past “transgression,” i.e., their decision to transition.

For a trans person who is considered “worthy,” Church leaders make clear that priesthood ordination and temple ordinances are permitted, but only “according to biological sex at birth.”[114] This statement raises intriguing questions about women and the priesthood, a topic that has been controversial within Mormonism for decades. Hypothetically, if a biologically assigned male physically transitioned to female but demonstrated ecclesiastical worthiness to their local leaders, would they technically be allowed to pursue the ranks of Church leadership due to their biologically male assignment at birth? Conversely, if a biologically assigned female physically transitioned to male but was not “visibly trans” in their outward appearance, could they serve in priesthood leadership positions? If either of these scenarios were to ever happen (or have already happened), it would certainly complicate gender roles in the Church and disrupt deeply rooted power dynamics that have long favored cisgender men.

The section on “transgender individuals” in the 2020 handbook has sparked a mix of hope, confusion, and frustration among trans Mormons. Perhaps the most encouraging part of the section is the caveat tacked on to the very end: “Note: Some content in this section may undergo further revision.” As well-known Mormon sociologist Jana Riess put it, “You can bet on it.”[115]

A More Pragmatic and Optimistic Direction for the Church

The fact that Church policies and doctrines are always subject to further clarification and revision can sometimes provide hope for sexual- and gender-minority Mormons. In fact, a core tenet of Mormonism is that God is always revealing new information and direction to the top governing body of Church leaders, also referred to as “prophets, seers, and revelators.”[116] This phenomenon is referred to as “continuing revelation,” which queer LDS writer Blaire Ostler defines as “the percolation of powerful ideas through a robust network of individuals and influences.”[117] Substantive and even fundamental shifts in Church teachings have occurred frequently throughout history, such as when Church leaders in 1978 lifted the long-standing policy that prohibited people of African descent from holding the priesthood and entering the temple. Because that policy was taught by prominent leaders as an unchanging and eternal mandate from God, Church members who desire changes to policies and teachings regarding LGBTQ+ issues see this decision to remove the priesthood and temple ban as a foreshadowing to comparable changes that lie ahead for sexual and gender minorities.

Nevertheless, considering that Church hierarchy is structured around top-down policy-making and ideological regulation, it is important that trans activists and advocates understand the practical realities they face.[118] LDS authorities have for decades asserted the illusion that they do not respond to outside sociocultural pressures and only make changes when God directs (though a critical analysis of Church history quickly reveals that this is untrue).[119] Such a notion that leaders make decisions in a God-inspired vacuum protects them from internal scrutiny and creates attitudes of credulity in the minds of members.[120] In addition, changes to policies and teachings occur at the discretion of male senior leaders, an undemocratic structure of governance that makes advocacy and activism especially difficult.

Pragmatic Changes

Understanding these limitations, I believe there are tangible and realistic changes that Church leaders can be expected to implement regarding policies and teachings that affect trans members. Leaders often express that altering Church teachings concerning sexuality and/or gender would contradict or even destroy “God’s eternal truths.”[121] However, recall the ways in which Juliana and Sarah explain their trans identities—i.e., they believe that their “female spirit” is their eternal, God-given gender identity. Many trans Mormons (particularly those whose experiences fall within the gender binary) feel similarly about their gender identities.[122] Because these concepts of gender fit into current LDS constructs of eternal progression, Church leaders could easily and swiftly begin to affirm binary transgender experiences. Blaire Ostler articulated this suggestion in her book Queer Mormon Theology:

The simplest explanation is that trans people do have a fixed, eternal gender which simply does not align with their body and/or gender assignment. Their spirit is “female,” but they were misassigned as “male.” A transgender person can claim to have an unchanged, eternal gender that is not in line with their assignment and still be consistent with the idea that “gender is eternal.” . . . However, while I can appreciate the argument for a fixed eternal gender, it does not address the needs of gender variant and gender-fluid folk. Of course, I do not blame transgender people who use this argument to legitimize their own experiences within the Mormon theological framework.[123]

As Ostler points out, a drawback of the “eternal gender binary” argument is that individuals who identify as gender-free, gender-fluid, genderqueer, bigender, or agender would still be viewed as contrary to or unaccounted for in God’s plan. Nevertheless, while far from ideal, this ideological shift would at least widen the tent of acceptance and affirmation for many trans members of the Church.

Another reasonable change that General Authorities and local leaders might implement is more resources and community support for trans members. Ostler suggests fifteen “ways to be more inclusive,” and one is to “hold special workshops addressing the needs of queer youth.”[124] Currently, there are very few support groups for trans Mormons within the Church—many people must look elsewhere to find them. Given that LDS leaders often express their desire to make the Church a more compassionate and welcoming place for sexual and gender minorities, implementing internal support groups and resources for trans people would be an excellent way to practice what they preach. Similarly, if leaders are truly striving to cultivate a sense of kindness and love for all, they must stop connecting transgender or gender nonconforming experiences to Satan or use any kind of pathologizing or “othering” rhetoric.[125] Instead, leaders and members alike can frame gender nonconforming experiences as different, not deficient. This would fit nicely with the popular LDS teaching that God is the author of diversity.

Optimistic Changes

Advocates who embrace more optimistic thinking for LDS gender minorities call upon Church leaders to reimagine and restructure the theological foundations upon which their religion stands. For trans Mormons, untethering theological frameworks from existing gender classification schemes is ultimately what is necessary for full liberation.[126] However, this push for liberation and equality is currently limited by theological assertions of who is eligible for participation in temple marriages (sealings), the capstone ordinance in LDS ritual and cosmology. Leaders continue to hold to the claim that only a biologically assigned male and biologically assigned female(s) can be efficaciously sealed for eternity in God’s plan. Female is plural because polygamous sealing rituals between a man and multiple women were performed in the nineteenth-century Church and are still performed today if a man’s first wife has died. (The current president of the Church, Russell Nelson, is a good example of this—he is sealed to his first wife, Dantzel, who passed away in 2005, and his current wife, Wendy Watson.)[127]

One reason LDS leaders cling to a heteronormative framework (even though LDS polygamous arrangements are arguably not heteronormative at all)[128] is that heterosexual biological procreation is considered to be an indispensable component of celestial relationships.[129] However, this emphasis on heterosexual procreation is rife with contradictions, as infertile cisgender heterosexual couples who do not have children, as well as cisgender heterosexual parents who adopt, are considered to be in harmony with Church teachings. In fact, when adopted children are sealed to their cisgender heterosexual parents, it is considered just as efficacious and binding as when biological children are sealed to their cisgender heterosexual parents. Conversely, if same-sex couples have children through artificial insemination, in vitro fertilization, or a surrogate, their family is not worthy of the LDS sealing ritual. Similarly, if a trans individual and a cisgender individual have a child through copulation, their family also lacks legitimacy in current LDS thinking. Indeed, this is perhaps the most egregious contradiction: a cisgender heterosexual couple who cannot have children is considered more legitimate than a cisgender-transgender couple who actually can have children.[130] Thus, the argument is not really about who can and cannot have children and more about a system of marking queer bodies and relationships as inferior to cisgender heterosexual bodies and relationships.[131] Ostler eloquently brings this inequity to light when she says: “The Church does not bar infertile cisgender heterosexual couples from being sealed because they are unable to reproduce. We seal them together and promise them eternal increase even when we don’t know what that will look like. It makes no more sense to prohibit homosexual [and trans] couples from being sealed to each other for the same reason it makes no sense to deny infertile, cisgender, heterosexual couples.”[132] She ultimately argues that “the ability or inability to biologically reproduce with our partner is not what makes a family a celestial family” but rather “our ability to rear children in love and charity,”[133] capacities that are independent of genitalia or sexual and/or gender identity.

Further challenging the notion that heterosexual procreation is superior to all else, Ostler points out that some of the most monumental births of Christianity did not involve heterosexual copulation. For example, according to biblical and LDS temple accounts, Adam was created by two males (Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ), and Eve was produced by three males (Heavenly Father, Jesus Christ, and from the rib of Adam).[134] Similarly, many Christian and LDS theologians and authorities teach that Jesus Christ himself was born from a virgin mother Mary without heterosexual procreation. In each of these milestone events, there is no account of heterosexual intercourse being a necessary means of reproduction or creation. (Some Latter-day Saints point out that Heavenly Mother may have taken part in the creative process, but there is no mentioning of her in scripture or LDS temple rituals.)[135] In any case, the fact that these divine creations occurred in non-heterosexual ways invites Latter-day Saints to expand their views of divine creation in ways that foster inclusivity and affirmation for non-heteronormative relationships.

For the Church to be a safe, welcoming, and embracing space for trans individuals, leaders need to reconstruct God’s divine plan either without the concept of a fixed eternal gender, or at least with the acknowledgment that all gender identities/experiences are equally valid in God’s eyes. While many mainstream members find this proposal radical and oppositional to divine teachings, such modifications harmonize with the most precious of LDS teachings—love, joy, and equity. Becoming like Jesus Christ (i.e., developing kind, loving attributes and helping those in need) is at the heart of LDS theology, a process that is independent of and transcends human classification systems like gender.[136] An often-echoed statement in the Church is “Christ is at the center,” an idea found in this commonly quoted New Testament scripture: “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”[137]