Articles/Essays – Volume 03, No. 3

Reflections at Hopkins House

“What’s your name?”

“Are you coming back?”

“I love you.”

These are the words of a Hopkins House child. Being young, very young, living in a poverty-ridden neighborhood, and possibly being a Negro are pre requisites for Hopkins House. Feeling a little social guilt could be the requirement for helping there.

As MIA president I am always looking for worthwhile service projects. I am happy that the girls are no longer encouraged to earn service hours at ward dinners, but are urged instead to find community work. The cooperative kindergarten my child attends has just lost its director to Hopkins House and the Head Start program. Inquiring of her if she might need young girls to help with the children, I became interested myself.

And so it begins.

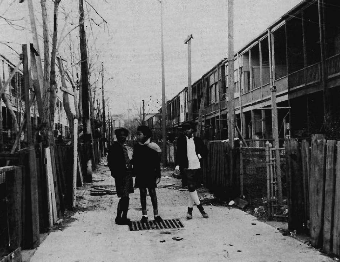

After I transport four well-fed, well-loved white children to the old but shining church in the beautiful Beverley Hills section of Alexandria, Virginia, I drive downtown along the railroad tracks and the truck route until I pass buildings that have seen better days.

I unchain the huge iron gate that surrounds Meade Memorial Church and enter the barren yard, where I am soon greeted by forty faces, some white, most black. I am assigned to work with three-year-olds. Ronnie, one of these, wears his coat and hat all the time, and is obviously sickly. (I wonder how these children would act if they were well.) Ronnie likes to be held. So I sing to him and rock him. Soon he begins hopping on one foot and smiling. And then—finally—he removes his coat.

The children are either terribly aggressive or painfully shy. On one occasion I turn to catch a two-by-four block just as Maurice is about to bash my head in. Soon after this he sinks his fangs into my arm. Maurice likes me; it’s just that he seems unable to express himself in any other way. I believe he bit me because he liked the story I was reading to Michael. Michael never says anything; he just looks right into my “Id” with his flashing black eyes. One day the Elders Quorum and their families picked up the children for a Saturday outing. I guess Michael is still too wary of white strangers, because instead of joining one of the families, he left, sad-eyed, with his mother.

Tony and Liza are girl cousins who live in the same house with two mothers and six or seven other children. Tony’s father stops weekly to see if Tony is being properly disciplined. Before he can get around to Tony, though, he must first discipline her mother. Liza always suffers quite a bit from Tony’s resulting tantrums. They are both beautiful little girls and surprisingly well dressed. One day, in a pretty dress with ruffled yellow panties, three-year-old Tony propositioned the minister.

All of the forty children are crowded into one room divided by sliding screens. We take the “Threes” outside early to provide more space for Fours and Fives. We go to the playground where there are three trees, one empty storage shed, and a wooden jungle gym, all surrounded by that huge iron fence. Once outside we ride the gate “train” to visit “Grandma in New Orleans.” She serves us cookies and punch in the shed. We spend one morning cracking walnuts and another throwing leaves. Fortunately the Elders Quorum has decided to buy playground equipment for next year.

One unusually warm winter morning I arrive at school to find the Threes anticipating a trip into Washington, D.C., to visit a beautiful playground whose equipment is a gift from Mexico to Mrs. Johnson. We pile into two cars and start out. As usual I get lost several times, but finally arrive with five children. Strangely enough all five, usually noisy and troublesome, have been so entranced with the ride that they simply gaze out the window with enormous eyes. We alight and tromp through the mud until the other car arrives. “Guess what,” is their greeting, “Whaletha has upchucked all over Mrs. Swenson.” Ah, Children!

Lunchtime at Hopkins House is always unforgettable. The children are served a good hot meal as soon as they can sit with some control. The first time I decide to eat with them someone warns me that I may lose my appetite. As I look around, I discover that thirteen of the noses I have wiped ten minutes earlier are now running profusely again. The children are eating soup with their hands, pouring milk onto one another’s heads. One of the more posh volunteers asks Steven if he would act that way if he were in a restaurant. Steven is puzzled by the word. He is one of the more rambunctious children and has a terrible time trying to sit still. Most days he is picked up and literally dropped, like a scratching cat, into the hall where he can kick, scream, and run into walls without disturbing the other children. When he comes back in, he is always welcomed by his twin sister who hugs him with her short, chubby arms and kisses his wet cheek.

One secret the director discovers just after Christmas is that if she gives the children one small box of dry cereal when they arrive, their whole attitude changes. A little breakfast is a wonderful thing! One morning as they finish their cereal I notice a little face I do not immediately recognize. She is standing next to LeRoy and wearing a torn plaid dress. Her face is emaciated, her eyes full of hunger, but she drops them when I look over. Finally, I reach out my hand. She clasps it quickly. She is LeRoy’s sister, it turns out, and has been ill with the measles. I lean down and pick her up. She wraps her matchstick arms around my neck, her frail legs around my waist and does not let go. I walk and sing, I rock and sing. She does not utter a sound. Many minutes later she releases her hold and sits back on my lap. She smiles a little, and then I must go.

Denise and Brenda are two little “Fours.” They dress up and fix meals all day long. I am sometimes invited to their corner for lunch. Before it can be served, however, I must be dressed in “beautiful” clothes and given a new hairdo. One Saturday I take Brenda and Denise on a picnic with my own family. It is a hectic trip, what with my husband constantly unravelling balloon strings from the necks of strangers. We are so busy trying to see all the animals and provide entertainment that we forget to relate to each other. This convinces us that our next outing should be spent at home. So next time we take Joseph and Derek to our patio for hot dogs and a visit to the garden. This time our visit is satisfying and relaxing. As we take the boys home, Joseph gives my daughter a quick kiss and runs into the house.

One day I find Tony in a particularly violent mood. She is hitting, biting, and crying. As I walk in, she runs to me, jumps into my arms and begins to sob. We hug awhile, then sing a few songs. There is a little toy vanity on the table, a gift from a retired doctor who has made it himself. It is beautifully crafted of wood with a large mirror set in the center. Tony pulls the vanity next to us, and we look in the glass together. “Look, Tony,” I say, “Our eyes are the same color. I wonder in what other ways we are alike.”

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue