Articles/Essays – Volume 26, No. 3

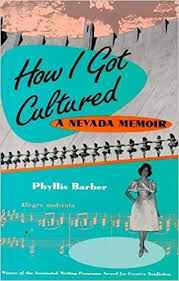

A Memorable Tribute | Phyllis Barber, How I Got Cultured: A Nevada Memoir

How I Got Cultured, Phyllis Barber’s memoir of her Mormon youth and adolescence in 1950s Nevada, has won accolades too numerous to mention. It has been warmly received in publications as mainstream and established as Publishers Weekly and the Kirkus Review. Nor should one neglect the fact of its winning the Associated Writer’s Pro gram Award for Creative Nonfiction. One can safely say this is a good book.

Having been raised in the Mormon faith, I recognize in her reminiscence the church that time left behind. Hers are memoirs of Mutual Improvement Association dances, ward talent nights full of shtick, “Rose Night” initiations for young ladies, and the insular attitudes which pitted the “Only True Church” against a hostile world. This particular conflict is well illustrated when, to wards the end of her narrative, Barber relates how, as a member of a highstep ping drill team, the Rhythmettes, she was asked to ride atop a founder’s day float sponsored by one of the casinos in Las Vegas.

Many of her achievements to this point had been motivated by a desire to be noticed, and in adolescence this de sire metastasized into something desperate (though still within the bounds of Mormon modesty). But upon learning that the parade is on Sunday, she winces over the consequences of breaking the Sabbath. She tries to rationalize that God surely will forgive her one trespass—to be a float queen for a day, after all. I wondered to myself then, as I had at many earlier points in her narrative, if a non-Mormon audience would find this as quaint as I did? Perhaps. Mormons are not the only people who try to keep the Sabbath day holy. But what are non Mormon readers to envisage in reference to stake road shows or visiting Maori dancers (with their special kin ship to the Nephites) or even, and especially, the dreams and solemnity to be found in a temple sealing?

This episode becomes less provincial and more poignant when Barber gets her gown fitted in the wardrobe room of one of the casinos and blurts out to a world-weary seamstress (and former Nazi concentration camp inmate), “I love God.” The seamstress does not reply to this non sequitur, though certainly the reader must infer from this silence that in the collision of the two worlds—the one containing Dachau and Las Vegas show girls, the other Boulder City and former MIA Maids— that “the love of God” is discourse which has lost its meaning.

Barber’s memoirs are gently satirical at times. I suspect the ironies and nostalgia will best be appreciated by “in siders.” Indeed, if the memoirs have any flaws at all, they are those passages where Mormon customs, rites, and beliefs are briefly summarized so as to bring the uninitiated reader up to speed. The didactic passages aside, there is still much that will be appreciated by all. But we are talking about a different sort of awareness and pleasure.

Many critics have found Barber’s memoirs to be a fine coming-of-age journal—and in this role it will speak to women of both feminist and more traditional attitudes. Beyond this, they speak intimately of a sort of Janus-faced culture. For example, Barber’s world at large is nestled ironically between the two great technological achievements of the century: the Hoover Dam and the atomic testing grounds. Her world made small, the Mormon world, is also polar. It is supercilious and silly in its narrow earnestness; it is also profoundly attached to values and affections not lost without a great sadness. Her book is endearing, and I believe, a lasting contribution. Church members who pass this title by will miss a memorable tribute, one which they alone will be best able to appreciate.

Phyllis Barber. How I Got Cultured: A Nevada Memoir. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992.189 pp.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue