Articles/Essays – Volume 11, No. 1

A Wider Sisterhood: Exponent II

Many readers were surprised and delighted when Exponent II burst upon the scene. “You have lifted my thoughts from the mundane and sweetened my dreams of fulfillment,” wrote one. Another commented, “A newspaper for Mormon feminists? Far out! Maybe there is a place in the Church for women like me.” Still another reader wrote that when she read through an issue, she wept, “not because the articles were particularly emotional, but because I had found someone, at last, who understood the feelings and thoughts I have had the past few years.” A young wife wrote that her husband was “floored to discover timely LDS-related articles.”

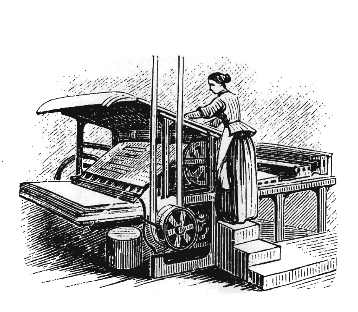

Exponent II, a quarterly, twenty-page, tabloid newspaper, was begun in emulation of and admiration for the Women’s Exponent (1872-1914), the first long-lived feminist periodical in the western United States. The publishers were domestic women who decided to put out a newspaper on the side. Could today’s women do the same? For generations the church community in the Boston area has been filled with bright young men aspiring for professional excellence and their equally bright wives who tended babies and kept house, but who still had a little leftover energy. Over the years this energy has been channeled into church work, community work and a steady stream of other projects.

One of these projects was A Beginner’s Boston, a guidebook first published in 1966 and revised three times since. It is still sold in Boston bookstores and has furnished thousands of dollars for the Relief Society and the welfare fund. The Cambridge Ward provided capital and encouragement, and the local women did the research and writing.

Then in 1971, Robert Rees, editor of Dialogue, entrusted a special issue of Dialogue to them, which became known as the “pink Dialogue” or the woman’s issue. What should such an issue contain? Some articles were generated locally, others invited from around the country and all celebrated faithful diversity. While some critics felt that hard-core problems had been evaded, others found the volume readable, supportive and inspiring. While working on the issue, the editors developed an understanding of the natural network of women in the Church obviously eager to be in touch with each other.

The next autumn some of the same women organized a class on nineteenth century Mormon women at the Cambridge LDS Institute which met with a different leader each week. This class may have been the first of many such classes held over the United States. (These informal presentations were later written up and published as a book, a collection of twelve essays entitled Mormon Sisters: Women in Early Utah.)

It seemed that after the Institute classes, not much was left to try. “Have you ever thought of putting out a newspaper?” asked one of the husbands. No, they never had. In fact, nobody in the group had ever even worked on a high school newspaper. On the other hand, simple news stories seemed easy after writing scholarly articles. People all over the country had interesting things to say. The paper could include information about study groups, reading lists, guest speakers. Such information in print would be a public service. Several members were skilled at layout, and others could do the typing, art-work and paste-up. All could do the writing. The group already had a good track record of the kind of cooperation needed for such a venture. The staff therefore incorporated as “Mormon Sisters,” a title later changed to “Exponent II, Inc.” In July 1974, the first issue announced itself as “poised on the dual platforms of Mormonism and Feminism”: with its purpose “to strengthen The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and to encourage and develop the talents of Mormon women.” That those aims were consistent they intended to show “by our pages and our lives.” While this was a heartfelt stance, most of the rhetoric of the paper tended toward whimsey, under statement and wit.

A feminine version of an old abolitionist phrase, “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” appeared as a slogan, but was later dropped because some people heard it as a battle cry. The first issue ran a neat eight pages. Each succeeding issue grew by four pages until the present twenty pages was reached.

Some people accused the group of publishing an “underground” press because, to them, the format looks a little racy. A swift perusal of the contents indicates otherwise. The format was chosen because it has a casual, throw-away quality. The paper was begun on a shoestring, “out of the grocery money,” and the first issue was distributed free. By the time a second issue was ready, enough subscriptions had come in to pay the bills. By limiting expenditures to hard costs (which meant no salaries), the staff kept the paper afloat. When Susa Young Gates published her Young Woman’s Journal, she paid her contributors “something, if ever so little,” (even herself). That “just compensation” has, as yet, not been possible for the present staff.

During its first year, the paper was regularly taken to task for blandness. No ringing manifestos, no hard stands could be found in its pages. Some said the paper was untrue to its glorious heritage—the first Exponent. Some readers were hoping for a tough stand on Church mores and practices. These criticisms always seemed naive to us. Courage is measured against its background. It took no great courage for the writers of the Women’s Exponent to criticize the national government which was daily violating the constitutional rights of the whole Mormon populace. The paper was merely echoing popular opinion. Brigham Young encouraged the spunky tone of the paper for it served as excellent propaganda to those who opposed polygamy on the grounds that it enslaved women. The more independent and lively, the better.

But the Women’s Exponent never criticized the Church itself, and people who think that Church leaders today would listen to strong stands are naive. Church leadership is democratic in that each faithful member gets the chance to run some small domain, but the power lines all run down from the top. There is no mechanism for criticism from the grass roots. In fact, critics are studiously ignored if not too vigorously excluded. The simple truth is that angry females, clamoring for their real or supposed rights, offend the canons of womanliness and femininity. The harder such women fight, the tighter the ranks close against them.

Church members have been more polarized by the woman question than they should be. If opposing sides could move past slogans and scare issues, they would probably find themselves in basic agreement. Exponent II encourages this unity in a wider sisterhood, believing that fighting is bootless.

In most cases repression is more often imagined than real. Ambitious women with unusual goals may not get much encouragement, but when they finally succeed, they are lauded. Rather than rage in print about the limitations that women suffer, Exponent II talks about the women who have prevailed over their difficulties.

Not all women can be nuclear physicists, but most can do a little writing and get their names in print. Unfortunately, many feel that other women have “talent” while they have none. They think writing, or painting, or poetry comes easily to the talented ones. Actually, writing is hard and painful for most of the people who do it. Those who go through the initial miseries, however, who revise their writing while accepting suggestions from others, can usually work up a publishable piece. The editors of Exponent II are happy to help in this process.

The paper has always felt as much responsibility to build the contributors as to entertain the readers. As a result, each issue contains material that probably would not be published elsewhere. Exponent II aims to “rise with the masses, not from the masses,” and a broad production of literary endeavors is necessary to that end. The aim is for participation as much as for excellence. On the other hand, graceful writing and pieces of real importance have been published.

It was feared that only known literate Mormon women would send in their pieces, but the representation has been surprisingly wide. Exciting pieces appear unsolicited. Everyone is invited to contribute—in each issue, by word of mouth and often by letter. A good percentage of what is received is published.

Beginning writers are published next to noted writers who have generously written for the paper or allowed their work to be reprinted. The stars receive no more billing than the lesser-known and less-skilled writers. Here we are all sisters (and some brothers) together. The inclination to identify writers by their professions, church assignments, number of children, degrees, or husband’s occupations has been resisted.

The personnel of the editorial staff of Exponent II has changed markedly since it began. Of the twelve original members, six have peeled off for various reasons. Most have moved away. The group is considered elitest by some, but the edges have always been loose. Anyone interested in being involved who is willing to work will usually be absorbed.

Many good Church members question whether a paper like Exponent II should exist within the Church community. Certainly those involved in the unofficial Church press take the risk of being misunderstood or dismissed as heretics. Many readers judge the writings of others by some undefined standard of orthodoxy. Certainly, the example of Dialogue has helped to upgrade the official Church publications and has provided a forum for unknown writers. (A recent anthology of church literature—A Believing People, compiled by Richard H. Cracroft and Neal E. Lambert—leaned heavily on reprints from Dialogue.)

An “outside press” can project a reality impossible in official Church magazines. An important justification for Exponent II is the preservation of Mormon women of the 1970’s in all their confusion, diversity and faithfulness. The paper aims to record the interchange between sisters for the future, just as the Woman’s Exponent crystalized the past.

Some pieces are peculiarly at home in an unofficial woman’s paper. Orma Whitaker’s skillful and moving poem is a good example:

After Surgery

No more brown eyed people will come to this house.

I have been hollowed and scoured and made

as polished as the inside of a drum,

and I echo with the silence of

unborn voices.

Come to me, all my children who will never be,

and I will tell you about the shortness of the summer

and how the pruned stubs throb.

We will be sad together for a while.

I have saved a lot of sighs to wrap you in,

and I will lay you down with songs of

how I might have loved you.

And then—goodbye.

Sleep softly. Murmur sometimes and I will

come to hush you in my dreams,

while all my days press forward, turning,

searching for another

season.

Women respond to this poem, sympathizing in sorrow with this peculiarly female experience. One reader said it was so good it should be “published.” (She meant really published!) Nearly universal, powerful and true as this poem is, it would probably not have found a place in the standard church magazines. Though it speaks of motherhood, the reality of the experience is too “negative” for a publication which by definition must be optimistic and proscriptive.

The editors of Exponent II may or may not have begun such a venture if they had known at the paper’s beginning what they now know. Much has certainly been learned in the process. After three years, the paper has a skillful and energetic core of workers and a faithful following. Financially healthy, it has always published on time. No power struggles, no schisms have marred its history. A group of sisters have done it together!

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue