Articles/Essays – Volume 28, No. 4

Balancing Acts

When Catherine opened her eyes on the Saturday morning of her daughter Kelly’s baptism, she recognized that the day ahead was going to test her endurance. Not only did she have to clean the house and do the laundry for Sunday, she also had to bake the refreshments for those who would come to her home after the ceremony. And somehow in there she had to include several hours of work grading seventh-grade English papers. She looked at the clock, 6 a.m., then past the hump of her sleeping husband to the window. The Hawaiian sun streamed in through the un curtained louvers, and just outside in the plumeria tree the myna birds had set up another ear-piercing morning caucus. Catherine usually arose at this time to prepare for another day of teaching seven periods of English to teenagers largely disinterested in the finer points of grammar and literature. But today she considered settling back among the pillows and sheets for another half hour’s sleep. The alarm rang.

Grant’s heavy hand fumbled in the air before smashing the buzzing into silence. “Who set that thing?” she demanded, knowing the answer.

He looked at her. “Some gremlin must have wandered in during the night.”

“Right,” she said. Then, “I don’t see why you’re so in love with the dawn. On Saturday, at least, we should be able to sleep in.”

“You will perhaps admit we have a lot to do today and an early start is the best start.”

She turned over, facing the wall for a moment before facing the inevitable. “Do you think,” she asked, “that Jason will come to Kelly’s baptism this afternoon?” Jason was their sixteen-year-old, and oldest, child. He was spectacularly inactive in the church.

Her husband shrugged. “You know what he’s said.”

“Yeah,” she said. That shit doesn’t work for me. Of course, he’d been angry at the time. Could he really have meant it? “Well, I’ll ask him again anyway. It is a family thing.”

“Good luck,” he said as if he didn’t care and went off to take his shower.

She thought of Jason’s baptism eight years before. They had just moved to Hawaii from Omaha, and to Catherine the idea of baptism in the ocean had so clearly been like the Savior’s. Back then Catherine was still at the point of wonder that she lived in Hawaii at all. When she suddenly came upon an ocean vista, saw the white-capped swells, the impossible blue of the expanse of endless water on a sunny day, the smooth, almost-white sand of the beaches against which the incoming waves curled and frothed, she wanted to throw out her arms and shout, “Thank you, God!”

But Jason was afraid of the water. His greatest fear was that a hundred-foot tsunami would roll in without warning and sweep away their house and the beds and himself while they slept. “Jason,” she had reassured him repeatedly. “The Lord will bless you. Nothing will hurt you.” And he and Grant had practiced together many times during the preceding Family Home Evenings, the holding of the nose, the bending of the knees, the falling backwards into the waiting arms of his father while the water covered him. Even so, Jason was reluctant.

On the day of his baptism, Catherine, Grant, their friends, and Ja son’s friends sat on metal folding chairs in the large lanai of a beach house the owner and the absentee landlord let the ward use for baptismal services. And Jason sat in white on the front row. Catherine sat next to him, holding the towels while the ward members sang and their home teacher gave a talk about the Holy Ghost. She noticed that his face was as pale as his shirt. Then as the guests and Catherine all stood on the shore, they watched Grant and Jason, followed by the bishop also dressed in white, wade out into the waist high waves. The three of them looked so dazzling standing there against the turquoise ocean, but when Grant had lowered Jason into the water, he had sputtered and kicked and fought to stand up. Streaming wet, red-faced now, Jason clearly wanted to head back to shore, but Grant held him with a hand on his shoulder. No one could hear what was being said, but finally after a moment Grant had raised his hand again and then pushed Jason as far under the water as he could. When the boy stood up again, everyone on the beach clapped and cheered—success at last—and Jason looked small, pale, and angry.

Was it possible, Catherine wondered for the hundred thousandth time, that they should have waited? But Jason loved the water now. He spent every free moment surfing with a ragtag bunch of friends, all of them browned to mahogany by the sun. His shoulders had broadened and he carried real muscle in his arms and chest from the daily swimming. He was a water baby. He balanced on that surfboard as if he were born to the waves. So that baptism couldn’t have been the sore that turned everything else about the church rotten in his mind, could it? But if it wasn’t that, what was it? She sighed and swung her feet to the floor.

By 10:00 a.m. Catherine was sitting at the kitchen table grading papers while the pies for the post-baptismal party baked when her best friend Leanne called from Seattle. The phone call was unexpected because now they usually only talked on holidays, but Leanne had an announcement to make. “I’ve joined the New World Church. And I want you to learn about it, too.”

They had been best friends since high school but became even closer when Leanne had been baptized into the church when they were eighteen. In the twenty years since then Leanne had never married. Instead, she’d built a career in television advertising. Sometimes Catherine envied Leanne’s business meetings, power suits, high rise condominium in Seattle, travel to Europe, and even her regularly polished fingernails, all of which she seemed to juggle with perfect poise. But Catherine knew that being a single woman in the church was hard, even dull maybe, especially when she was surrounded by the kind of high-powered executives she dealt with. But this news was a shock. After a small silence, Catherine said, “I’ve already got a church. I thought you did, too.”

“This is better,” Leanne said. “You’ll love it.”

“What is this proselyting attempt here?” Catherine said, “Is this like some pyramid scheme, where you get more points for bringing in new suckers?”

Leanne laughed, although Catherine hadn’t been joking. “How can you even say that after the way the church goes after new members? Remember how you practically threw me into the baptismal font yourself?”

“That is a more than slight exaggeration, Leanne. And just what exactly do you mean by ‘better’? Do you really mean easier?”

Leanne said, “It is easier, as a matter of fact. There’s no Word of Wisdom. There’s no tithing. There’s not even any repentance because we don’t believe in evil. But that’s not the point. I feel as excited about this as I did after I joined the church. Remember how you told me I had the Holy Ghost then? That’s how I feel now.”

Leanne still said “the church.” What did that mean? Catherine wondered if Leanne was remembering all the details of her baptism. She’d been excited all right. It had taken her two years to unload an old boyfriend and commit herself to going under the water, and sometimes Catherine had wondered if she’d been converted to the missionaries more than to their message. She’d always told Catherine she loved their bright eyes, “their thousand-watt smiles,” their chipmunk eagerness to share the gospel. When Leanne told Catherine over the phone that she’d actually set a date for baptism, she’d said, “It was like one voice was coming out my mouth saying ‘yes’ to the elders when inside my head another voice was screaming, ‘What? Are you nuts? Tell them no!’ But I’m not sorry,” she added. “I’m definitely going to go through with it.” Then on the appointed day she’d shown up late. Catherine and the two elders had hung around the meetinghouse parking lot kicking rocks and wondering if they were being stood up. Finally, Leanne’s little red car had turned in from the road, fast, raising a cloud of dust behind her. “I just came to tell you,” she announced rolling down her car window, “I am not in a good enough mood to go through with this.”

A few minutes later, after some fast talking on Catherine’s part, Leanne had changed her mind again. “OK,” she said, “let’s get it over with.” As she walked down into the baptismal font, she’d raised her hands for Catherine’s inspection. “Look,” she said, “they’re trembling.” Yet, just seconds later when Elder Barker lifted her out of the water, her face had become, almost, luminescent, and a tangible calm had descended in her eyes. “My life is an empty pit,” she’d always said only half-jokingly all through high school as she considered her alcoholic mother and other disappointments. On her baptismal day she had spread her arms and shouted, “My life is a full pit,” then laughed with joy while pirouetting as gracefully as a ballerina.

Which feelings was Leanne remembering? Catherine said, “Leanne, what about the church?”

Leanne thought while the long distance lines hummed between them. Finally she said, “I’ll always be grateful for the stability my years in the church brought me. That prepared me for what I’ve found now.”

“How can you just walk away from the gospel like this?”

“Catherine,” Leanne said gently, “it was as easy as falling off a log.”

***

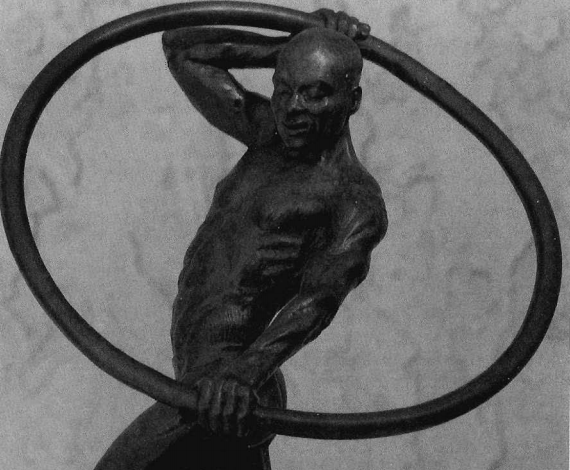

As easy as falling off a log. Catherine thought about that for the rest of the afternoon. She’d seen logrolling competitions, hadn’t she, the lumberjack standing on the log, trying to keep his balance while the log rolled beneath his feet, every second in danger of losing his footing. What happened when he finally fell, she wondered. Did he welcome the descent into cool, clear water after all that sweaty exercise? Catherine felt sweaty right now, especially as she looked around her kitchen.

Fourteen-year-old Cara was supposed to have done the dishes on Thursday night. Because Catherine taught at the high school, her kids were absolutely expected to help with their share of the housework so she could keep all her balls floating in the air at the same time. But dirty pots and pans, dishes and glasses, nearly fossilized, were piled on the counter. Thirteen-year-old Ronald’s skateboard and backpack were slung in a corner, appropriately arranged, Catherine realized, for a near-death encounter with anyone who wasn’t looking. She fully expected that one day she would stumble over the skateboard with a load of laundry in her arms and take a short but unforgettable ride careening through the house out of control. Meanwhile, the lawnmower, suggestively placed in front of grass so high it had gone to seed, stood neglected by Jason. The teenagers had scattered, dropping every detachable appendage as they left. Ron and Cara always claimed studies at the library, or a Young Women’s project, or work, or babysitting, or anything else they hoped she would believe. But Catherine was morally certain that the three of them were cruising the mall with some unlicensed, uninsured, underaged driver. From the living room Catherine heard the theme music from The Last Action Hero and knew that Kelly was watching that movie, theoretically edited for television, for the fiftieth time. A perfect mother, she realized, would have this same eight-year-old immersed in some creative project involving construction paper and imagination rather than letting her fry her brain and eyes in front of the television set with another Arnold Schwarzenegger fix. She also realized that a perfect mother would have long ago organized her children into an efficient cadre of happily working helpers, especially on a day like today. Instead, she usually seemed to be bouncing from one emergency to the next. She needed her husband here today to crack the whip a time or two, or at least raise his voice, but he was at an afternoon meeting of the stake high council and was probably excommunicating some hapless soul at that very moment. “I am not in control here,” she said aloud.

“What?” Jason walked into the room and looked at her as if he was weighing the possibility of having her committed. After a second he turned to forage in the refrigerator, then announced, “There’s nothing to eat.”

“You mean there’s no junk food,” she said.

“Yeah,” he said. “How come you guys never buy any decent food?” She was always glad to see him, always glad to see he was still alive, not drowned, not crushed in a car accident, not overdosed on some drug. But he also had a tendency to infuriate her within seconds.

She said, “Are you coming to Kelly’s baptism this afternoon?”

“What?” he said, as if he had suddenly been stricken deaf.

“You heard me.”

“Uh, Mom,” he said, “you know baptisms aren’t my thing. And, uh, well, I have plans for this afternoon.”

Catherine didn’t ask him what his plans were because he wouldn’t tell her and she didn’t want to know anyway. She also didn’t want to irritate him. “Jason, she’s your little sister.”

“So?” His face looked as if he really expected her to explain why the family relationship might be important.

“We love you, you know.”

“Oh, that’s right,” he said. “Lay a guilt trip on me.”

The problem, Catherine decided, was that she probably wasn’t as smart as he was. But she did love him. “It would mean so much to me, to your father, and to Kelly if you would come.”

He slammed the refrigerator door shut, apparently rejecting food for the moment. “I’ll think about it.”

“What more can I ask?” she said, striving for a lack of sarcasm, and realized she felt dizzy. Maybe I need to eat something, she thought.

***

Grant came home about 3:30 and peeled off his suit coat and tie, laying them on the couch before he came into the kitchen. Catherine frowned. She’d told him a thousand times that he made her feel like a maid when he dropped his clothes on the furniture.

“The bishop talked to me about you,” Grant said.

She continued tossing the salad. “Why?”

He shrugged. “He put it real politely, but basically he thinks you talk too much in Sunday school class and wants you to shut up. Last week Sister Spangler nearly had a heart attack when you announced Relief Society work meeting wasn’t vital to your eternal salvation.”

“I was just making a joke about priorities,” she said, slicing a tomato with quick, sharp strokes. “About how you need to maintain a balance between what’s important and what’s not.”

“You intimidate people,” Grant said. “Some people don’t understand your jokes. Some Relief Society teachers apparently want to go home and slash their wrists after one of your incisive comments.”

She turned, the knife still in her hand. “Do I intimidate you?”

He looked at her thoughtfully. “No.”

“I wish I intimidated Jason.” She waved the knife in the air. “And Cara and Ronald for that matter as well. I wish I scared the hell out of them.”

“Literally,” he said.

“Yeah,” she turned back to the salad. “By the way, Leanne called today. She’s leaving the church. She says she’s found something better. She can smoke and drink, among other things.”

“I doubt that’s anything new in her life,” Grant said.

“Maybe if she’d found a good man,” Catherine said. She tucked the salad bowl into the refrigerator.

“Honey,” Grant said, “she’s found a dozen good men. She just keeps turning them into toads with her kisses.”

Leanne had backed out of marriage at the temple doors at least twice and discarded a number of other suitors when they got serious. “Well, maybe they weren’t ‘the one.'”

Grant said, “Which one is that?”

“Oh, you know—the one. The one you promise to marry in the pre-existence, the one you save yourself for. The one you meet after all kinds of trials and tribulations and know immediately that you’ve recognized your eternal love. And you know your life will be perfect if you can just dance your way through courtship and make it to the altar a virgin.”

Grant raised an eyebrow. “Like you recognized me?”

Catherine’s pre-nuptial jitters had become legend. Her old friends still talked to her about it. Still, in spite of her terror, she’d gone ahead with the wedding because she kept getting answers to her prayers. And she wasn’t sorry, usually. “Well, you know,” she said, “I was neurotic. Every time I thought about spending the next fifty billion years and more with you, my stomach bloated.”

“Especially since you were marrying a nerd like me,” Grant said.

“Even if you’d been cool, I would have been nervous,” she said. “Forever was a long time.”

Grant laughed. “It still is, you know.”

“I know,” she said, thinking about how much both Sister Spangler and the bishop ticked her off.

***

At 5:00 p.m. Catherine and her family sat on a row of metal folding chairs on the same lanai where Jason’s baptism had taken place. Kelly sat beside her, dressed in a white choir dress, next to Ronald and Cara who had reappeared at 4:49 to walk up the road to the beach house with the rest of the family. Jason was not in evidence. Grant was running around setting up more chairs and shaking hands with the friends and neighbors straggling in. There was no piano, so the singing, such as it was, would be a capella; and no microphone, so the talks would be largely unheard by those in the back. It was the spirit that mattered, Catherine told her self. Ronald, as one of the speakers, looked appropriately solemn, clutching a small piece of paper with suspiciously few notes scribbled on it. Ronald was the type to take a request for a short talk literally.

Although the sun over the ocean was low in the sky, it had not yet sunk toward the horizon. The light in fact was luminous, magic hour as the photographers called it, where the sky, the trees, the grass, and the water glowed as if with an inner fire. This radiance lasted only a few moments in the tropics before the sun dipped into the ocean and quite suddenly disappeared, leaving the world swathed in black night. Usually ocean baptisms were held at dawn, but Kelly had requested this late afternoon baptism, just before the sunset, so she could fall into bed almost immediately and rise up in the morning and go to church a full-fledged member. Kelly, Catherine realized, looking into her daughter’s eager face, thought she was going to be a whole new person when she came up out of the water. Born again, Catherine thought, into a world of temptation and paradox.

Catherine’s baptism had taken place at age thirteen when her entire family had been converted to the church by the stake missionaries. She remembered sitting in the little room adjoining the baptismal font, smelling the chlorine, and hoping that two white slips under her dress would be enough to keep the cloth from clinging to her budding curves once it was drenched with water. Her mother, her father, her sister, and her two brothers sat beside her, all of them nervous at the step they were taking, committing themselves this way to a life of caffeine-free, tee-totaling church-going. Many ward members had gathered for that occasion since her family had been attending church regularly for several weeks. Sister Olmstead, the Young Women’s president, was there with a load of towels; and Sister Miller, the Relief Society president, had organized the white clothes for the six of them.

When organ music rolled over the little assembly, Catherine had sung the unfamiliar hymns in the hymnbook Sister Miller handed her. She bowed her head with the prayer and listened with grave attention to the elder’s talk on the gift of the Holy Ghost. She fully expected to feel a purifying fire when the missionaries laid their hands on her head to confirm her a member of the church, the mighty change they had promised to occur immediately. With interest, she had watched first her father, then her mother, walk down into the font dry and composed, then come up dripping water, hair plastered to their skulls, changed at least for the moment. Then it was her turn, and she floated down the steps as if in a trance, was grasped by the missionary’s firm hands, listened to the words of the prayer, then sank down into the warm water and was raised up again, to be quickly covered by the towels Sister Miller had at the ready. Had she felt peace, Catherine wondered now, or had she simply felt unreal? For certain, when the elders had laid their hands on her head to give her the gift of the Holy Ghost, she had not felt the cleansing scourge she had hoped for. Instead, when she stood up again, she felt disoriented, turning slowly in a circle to shake the outstretched hands. The imprint of the priesthood’s palms still lay heavy against her scalp, even though the hands themselves were gone. That weight held her feet steady against the floor, keeping her from drifting off out of reality all together.

Sister Olmstead had left her husband and run away with another man a year later. Sister Miller had gotten cancer and died bald, and her husband had left the church. But Catherine stayed, went to seminary, read the Book of Mormon, prayed beside her bed every night, attended BYU, married in the temple, and now walked the tightrope between maintaining her own faith and trying to raise her children to love the gospel. Her best friend had defected. And Jason wasn’t there at his sister’s baptism. Catherine wondered what Kelly would remember of this day as she made her life choices.

***

That night after the guests were gone, the apple pies demolished, the fruit punch reduced to red stains at the bottoms of paper cups, Catherine lay in bed next to her husband and said, “Did Jason come in?”

Grant said, “He’s been holed up in his room for quite awhile. He came in at the last minute, grabbed some pie and punch, gave Kelly a hug, then retreated to his bat cave.”

Catherine assessed this information. He’d been home all the time. She said, “Life is such an emotional roller coaster ride, sometimes I wonder if I’m going to endure to the end.”

“You will,” he said.

“What’s to keep me going?” she said. “So many people, strong people, seem to fall away. And Leanne and I are like twin sisters.” She paused, “Or we were before you came along.”

“You know why I decided to marry you? It wasn’t because you were perfect.”

“Big surprise,” she said.

“Yeah,” he said. “You were so neurotic about the wedding. A lot of people told me to get out while I still could.”

“I know,” she said. She’d heard these stories before. “You were very brave to take me on.”

“No, you were brave. You stayed. Leanne always runs away.”

“And you know,” she said, “our marriage hasn’t really been too bad.”

“Most days,” he agreed and kissed her cheek.

After he went to sleep Catherine lay next to him and thought about Leanne’s phone call. Leanne had said, “I think you’ll really be interested in the New World Church.”

“Why would you think that?” Catherine asked.

“Well, I always have seen you as a rebel in the church. Didn’t you tell me once you were such a troublemaker in Sunday school class and Relief Society that teachers flinch when you raise your hand?”

Catherine had smiled. “I’m not a rebel, Leanne. I struggle, that’s all. But the church is my life.”

“I’ve known you twenty-four years,” Leanne said, “and you can still amaze me.”

“I don’t guess you’ve known me if you haven’t known that,” Catherine said, not gently at all.

In the dark beside her snoring husband Catherine’s eyes burned with grief for the lost ones, and tears lay hot tracks across her cheeks for the ones who failed, the ones whose hearts could not hold steady. Sometimes the world seemed so full of traps, especially in the dark, as if evil lay in wait to swallow them all up if they stumbled one too many times. But that night she dreamed she was dancing on the foamy crests of towering ocean waves, nearly tipping over sometimes, often catching herself just before she fell, but usually upright, straining with effort, giddy with exhilaration, and frequently held in place by a strong and certain arm.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue