Articles/Essays – Volume 25, No. 4

Before the Wall Fell: Mormons in the German Democratic Republic, 1945-89

On 9 November 1989 the world stood transfixed as television sets around the globe transmitted the fall of the Berlin Wall. Hundreds of thousands of East Germans streamed into Berlin to mount the wall or walk through the hastily broken holes in that once formidable barrier. What virtually all of them had longed for for so many years—to leave their fortress prison and travel into the West[1]—had become a reality. Some Latter-day Saints were among the throngs throughout East Germany on that historic evening who ran out of their houses to ask each other if what they had seen on television was actually true—forty years of official lying and deception had bred skepticism—and then hugged each other in glee when their hopes were confirmed (Schulz 1991).

Since that memorable day, much has happened: Once invincible, swaggering tyrants have been overthrown and are being brought to trial; secret police files have been confiscated and are being processed; free and open elections have been held; Germany is once again united. One somber epoch of German history has come to a close, and a new one has begun. German Latter-day Saints are also beginning anew. Members like Andreas and Ingrid Ortlieb and other Berlin Saints, formerly part of the cloistered GDR Mormon community, are now members of stakes realigned to include Saints from both the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). Missionaries from all over the world arrive weekly in Dresden and Berlin while local missionaries depart regularly for the four corners of the earth.

With this change comes the opportunity to sketch for the first time an outline of the unique experience of the largest Latter-day Saint community in the Communist world, and to consider how both local members and Church leaders coped with a regime and society whose official principles, leaders, and institutions were largely antithetical to Mormon doctrines and ethics.

Is there something here that may have wider application? Does the German experience provide any guidance for dealing with other authoritarian and non-democratic societies? How did those forty years affect the Church in the GDR, its leaders, and members? What has been the dialectical relationship between continuity and change in this Communist setting? I believe the answers to these questions are, in general, positive. There is a great deal that Latter-day Saints, and other Christians, learned from this kafkaesque prison society about the nearness of God and the human condition. These four decades reveal extraordinary examples of faith, commitment, sacrifice, patience, familial and brotherly love, and dedication. But there is also much to be learned about discouragement, desperation, disappointment, resignation, impatience, and waywardness. Despite the stabilizing and protective cocoon of Church values and fellow members support, Saints in the German Democratic Republic did not live in a vacuum. Along side their fellow citizens, they had to cope day in and day out with an insecure and arbitrary Communist society, its ubiquitous, informer ridden police-state and single-party system, educational indoctrination, propaganda, and its fundamental antipathy toward religion. Every where there was, as Gerd Skibbe has written, the violation of the right of agency, the heart of the Communist system. In addition, they experienced an even distribution of poverty (except for privileged party officials), a drab, often polluted environment, and everywhere dilapidation, deprivation, political bondage, and often hopelessness, at least for this life. Above all, there was the ever-present angst[2] and the conviction that only Christ’s coming would overthrow the system.

Another side of the story, however, must be considered. Communist leaders loudly trumpeted ideals of a new society built upon real social justice, with unbelievably low costs for basic foods and tolerable housing, freedom from the fear of unemployment, a high standard of living—ironically propagandized as western-style “materialism”—”cradle to the grave” medical care, and the absence of crime, pornography, violence, and a host of other social ills that plague free societies. Most of these Utopian dreams never materialized, but some features in the GDR society did correspond to Christian ideals, such as narrowing the gap between rich and poor and minimizing capitalist greed.

Over our fifteen-year association, Walter and Edith Krause, life time residents of Prenzlau, often spoke of some “positive” features of the GDR. They had as little affection for the excesses of capitalism as they had for the limitations on personal freedom of the GDR Communism. In a letter dated 22 March 1990, Edith wrote, “Not everything in the DDR [Deutsche Democratic Republic] was bad and may the good now save all Germans.” Similarly, many intellectuals in what were formerly East and West Germany, like Giinter Grass, Stefan Heym, and Christa Wolf, lamented after reunification the crude mate rialistic avalanche of Western capitalism, the harsh and greedy elbowing aside [Ellenbogen-rammelei] of local people with little attention paid

to what they considered significant social gains in the GDR. The Mormon history in the GDR is scarcely intelligible without some historical background. Since the 1850s Mormonism had, by German standards and with some setbacks, prospered in this overwhelmingly Protestant area.[3] In fact, in 1930 there were more Saints in Germany (11,596) than in any other country of the world outside the United States, including Canada (ll,306).[4] In addition, this small but significant Mormon presence had been strengthened by many families, like the Max Schade family in Dresden, who, like many other LDS families following the counsel of Church leaders, had long since decided not to emigrate to the United States (Krause 1991).[5]

By the 1930s, then, approximately 8,000 members lived in eastern Germany, roughly east of the former FRG-GDR border. They were scattered among more than sixty small branches and several larger ones (over 500 members) in Dresden, Chemnitz, and Berlin, as well as in the smaller branches in Konigsberg, Stettin, Schneidemuhl and Breslau. All these latter branches were dissolved in the spring of 1945 as their members fled west before the advancing Red Army and East ern Germany was annexed either to the Soviet Union or to Poland.

Although the wars, especially World War II, had exacted a heavy toll of the young LDS men[6] in a church where men were needed and less plentiful, partly because they were less often converted, devastation and existential consciousness had also strengthened the survivors’ faith. According to Manfred Schuetze, former president of the Leipzig Stake, who in the late 1980s conducted a series of interviews with eleven elderly GDR Saints, most were more determined than ever to adhere to their religion. Many had found that Mormonism, even without the full organization or temple ordinances, more than met their spiritual needs in the most trying of times (Schuetze ca. 1989). There were those—and not just a few—who, uprooted by the incredible tur moil of war, were part of a massive twelve-million-strong refugee band that clogged the roads going west ahead of the triumphant Russian army. Some had decided that only America—usually meaning Utah—offered them the security they craved. Others were content to relocate in what later became the Federal Republic of Germany; but many, with some anticipation of eventually returning to their homeland and recovering their lost property now annexed to Poland or incorporated into the USSR, settled in the area that would soon become the GDR and quickly found needed places of acceptance and serenity in the Mormon communities there. Walter and Edith Krause, Hans and Elli Polzin, the Meyer family, Walter Schmeichel, and Otto Krakow are a few of those refugees who settled in the GDR (Schuetze ca.1989).

Here, then, was a chastened folk, most of whom had been sub jected to the horrors and humiliations of war. In fact, many of the early Church leaders in the GDR had been prisoners of war, most often in the hands of the Russians.

Some also suffered a sense of guilt for having helped bring to power a Hitler who had unleashed his hatred and misery on the world. These shaken survivors now clung to a faith and community that had sustained them in difficult times. Little did they know that, with the exception of the actual war years, the challenges that lay before them would include hardships and trials even more difficult, longer lasting, and more corrosive than ever.

With some exceptions, the Mormon experience in the GDR con forms to the larger history of other Christian churches and sects in Communist-dominated countries. That is, the same policies governed Mormons that were applied to all churches, even though throughout the forty years the Mormon church, considered a “sect,” a term more pejorative in German than in English, had little institutional contact and no common program with other Christian churches, a policy carried over from earlier and less happy decades.[7] Churches were, in fact, the only large organizations in the country that were not Socialist (Communist) and not state controlled. This condition of limited independence had also existed during Hitler’s Third Reich. Moreover, almost from the first, the GDR constitution, especially Article 39, guaranteed autonomy for all churches and later a modicum of religious freedom (Zimmerman et al. 1985, 1:715).

At the same time, the ruling SED (Socialist Unity Party) and all of its appendages were from the outset resolutely anti-church and anti-Christian. Marxism-Leninism was the official new “religion,” and the “enlightened” were not only to believe it but to promote it. Party faithful and other aspirants for power were encouraged to renounce church membership and any religious commitments. Church membership did, in fact, decline throughout the period (Zimmerman et al. 1985, 1:715).

The history of all GDR churches can be further divided into five different eras, each reflecting a particular government policy: (1) 1945-49, the years of Soviet Army Occupation (SMAD); (2) 1949-58, the period from the founding of the GDR through the harsh Stalinist fifties; (3) 1958-68/9, when party boss Walter Ulbricht worked diligently to establish international legitimacy as well as a separate identity for the GDR both at home and abroad, in part, by separating Protestants from their ties with the Protestant Church in the FRG; (4) 1969-78, when the government, under Erich Honecker, using a more carrot and less-stick approach, worked to weaken religion as a promoter of German unity and strengthen instead GDR Protestants’ loyalty to the GDR state. This put Mormons in a somewhat better light because of the Church’s long-term policy of encouraging members to stay in the GDR and get along with, if not necessarily support, the regime; (5) 1978-89, when churches were encouraged to accept “socialism”—and, in part, did—and contribute to the building up of the socialist society under the rubric of “limited cooperation with tension.”

I will now briefly sketch both the external and internal dynamics for each of these periods and then draw some conclusions.

1945–49

For those raised during the long Cold War period, it may be difficult to comprehend the general good feeling that prevailed among the wartime Allies for a short time after World War II until the Iron Curtain fell in 1946. The vaunted Nazis had been conquered, and there was great hope that Allied cooperation might have dispelled the pre-war threat of Communist aggression. Such optimism did not, how ever, extend to most Germans, especially to the refugees from the Eastern territories who had only recently experienced harrowing brutality, barbarism, and rapine at the hands of Russian soldiers.

As the war ended, however, Russian-occupying authorities exhibited unusual goodwill to Church leaders and members. According to Arthur Gaeth, an American correspondent in the Russian Zone and former Mormon missionary in Germany, General Vasili Sokolovsky’s 1946 order permitted regular Church services; Church representatives were allowed to travel freely (there were thirty-one local German missionaries in 1946), and a 60,000-volume cache of genealogical and Church records was sent to Utah. In addition, two automobiles were made available by Russian occupation authorities to Church authorities. The Church would be permitted to publish tracts when paper became available and in June 1946 held a mission conference in Leipzig. One Russian general, Dratwin, upon learning that the Russians were more cooperative than the Allies, even suggested the Church move its headquarters into their zone (Gaeth 1946).

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of Elder Ezra Taft Benson’s 1946 visit to Europe, but especially to the Saints in the Russian Zone. Not only did he bring them hope for welfare support and relief—food and clothing for a cold and starving people—but nourishment for their spirits as well. He strengthened their faith and, as Walter Krause remembered, counseled them to “put away your hatred and bitterness and help build up the work of the Lord” (Krause 1990). German Saints were euphoric to see and hear an apostle and learn that the Church—its authorities and people—was aware of them. This meant that the spiritual lifeline that had been severed in 1939 was again restored. They were once again united with the Mother Church in Zion.

Don Corbett, an American serviceman, vividly described Benson’s visit to a badly damaged schoolhouse where 480 Saints and friends had gathered in the summer of 1946:

The German Saints were in their places when Elder Benson arrived. They all stood up when he entered and made his way to the stand. It was a wonderful sight to look into their faces and feel their devotion and gratitude. An air of great expectancy was there as well as a certain tenseness. Everyone anxiously awaited for the servant of the Lord to commence speaking. There was also a note of sadness. As the eye took in the scene and beheld the emaciated faces, etched with sorrow and tragedy, a feeling of sympathy was kindled for them. Many were suffering from stages of malnutrition. Some were in great need of medical care. On this day, however, their spiritual desires transcended their temporal wants. These were the faithful, the backbone of the Church in Berlin, but many of them needed encouragement and needed light and guidance to set their thinking straight, (in Babbel 1972, 61)

Elder Benson’s message, spirit, dynamism, love, and concern, together with numerous spiritual manifestations, also reassured these bereft Saints of God’s love and concern and strengthened their courage to meet the formidable rebuilding challenges ahead.

Welfare supplies, which began to arrive in 1947, reinforced their hope, and Walter Stover, the gentle, generous, ingenious man who had been called as East German Mission president, followed in Benson’s footsteps. Time and again Stover displayed generosity and resource fulness as a traveling minister and shepherd. His big Pontiac was recognized everywhere, and his unadorned plea to President Cornelius Zappey in the Netherlands for food captures his heartfelt solicitude for his people: “My people are so hungry” (in Sonne 1988, 167).

Equally important in those first post-war years were the extra ordinary expressions of faith exhibited by families who, in those most dire conditions, accepted calls extended primarily to fathers and sons to serve as missionaries. They went without purse or scrip, gathered the faithful together in branches, found places to meet, preached the gospel, baptized converts, and presided over branches. Probably because of the humbling experiences of the war, they found many fellow Ger mans interested in their message, a condition less noticeable in the more prosperous times that followed.

Missionaries later spoke of their experiences: Walter Krause left on 1 December 1945 “with 20 marks in my pocket, a piece of dry bread and a bottle of tee”; Eberhard Gabler, who served for thirty eight months beginning in 1947 said: “It was the most profitable time of my life”; Walter Bohme, Walter Ritter, and Herbert Schreiter, who left a wife and children behind on his second mission, also served; and Paul Schmidt left in the summer of 1946 at age forty-one and served fifty months (ca.1989, 3, 30, 46, 50). The Saints’ commitment in those early days also appears in the numbers who attended the first mission wide conference held after the war (Leipzig, 5-12 June 1946). A later description gave the details:

The Russian authorities permitted extensive advertising. The radio carried announcements three times each day for two weeks in advance, posters were on every billboard in the city and in every streetcar, so that by the time the conference began, nearly every person in the area knew it.

A total attendance of 11,981 participated [in all combined meetings]. The Sunday evening meeting alone was attended by 2,082 persons—by far the greatest attendance even (to this time) to be present at a meeting of the Latter-day Saints in Europe. At a special concert, featuring a mission-wide chorus of 250 voices and an orchestra of 85 pieces, which was held on Monday afternoon[,] 1,021 were in attendance, and at the Gold and Green Ball that evening 1,261 participated. (European Mission History, in Babbel 1972, 112)

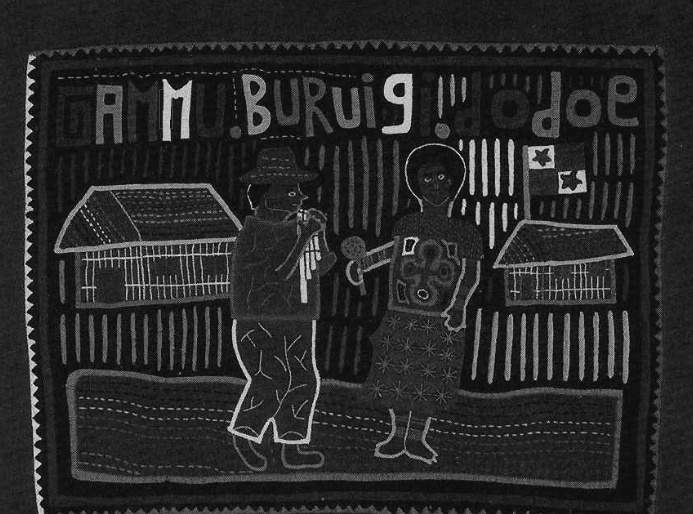

For many these years, building upon powerful spiritual experiences from the war years, were a time of enormous spiritual growth which would, in fact, nourish them for a lifetime and beyond. Many of these Saints would not only become stalwarts in raising strong Latter day Saint families which became the backbone of the Church as con verts diminished under government censures, but they would, for three and four decades, also provide the leadership for the Church in the GDR until a new generation could be reared to take their place. Many leaders served for twenty years and longer. Henry Burkhart, the de facto mission president, for example, served in a leadership capacity for over forty-six years.

1949–58

As the occupation era ended and the German Democratic Republic was founded in 1949, the Mormon community had, in fact, taken shape, although some Saints continued to emigrate. An estimated 4,000 Saints lived in the Russian Zone in 1946; twenty-one years later the official number was little different, 4,740 (Gaeth 1946; MH, East Ger man Mission, ca.1968).

By 1949, the Cold War had chilled conditions. The Berlin blockade symbolized the new reality; Stalinism, which would characterize much of the fifties and sixties, descended on the GDR in all its fury. An entire generation was, as Roder has argued, indelibly stamped with the experiences with the Stalinistic regime of terror (Roder 1992, 449). Government policies and attitudes toward religion, which would permeate the whole era and the new bureaucracy, were slammed into place. Strong atheistic and anti-Church propaganda dominated the era; party leaders and government functionaries of every level were encouraged to withdraw from church membership. Many did so. Dur ing the next twenty-seven years, Protestant ranks in the GDR were cut in half (Zimmerman et al. 1985, 1:715, 721). The Catholic Church does not appear to have suffered comparable losses, although in a survey of fifteen- and sixteen-year-olds in the former GDR, over half said they did not believe in God and 86 percent did not belong to any religious group (“Growing Up” 1990, 14). Religious education was taken out of the schools; church activities, outside of worship, were severely curtailed as the SED, in true totalitarian fashion, moved into many of the social and cultural realms churches had previously filled.

Churches were hampered economically as well as ideologically. Church buildings were neither built nor rebuilt, and materials for repairs were difficult to come by. Finding and retaining branch meeting places was extremely difficult (Schuetze ca.1989, 11, 18, 19, 31, 34). Walter Krause’s job was to keep the meeting places in repair, but it was often a hopeless task because of bureaucratic red tape, lack of building materials, and endless waiting in lines. The traditional church tax became a voluntary offering, and party leaders attacked church youth groups. Though the assault was full scale, pastors and priests could still be educated, and church-owned land was still exempt from collectivization (Zimmerman et al. 1985, 721).

Latter-day Saints experienced even more difficulty because of their small size and American connections. Very soon, the government and the ubiquitous Stasi (secret police) labeled the Church as an American spy organization and regularly placed informers in its meetings. The Saints hunkered down to battle for self-preservation. Missionaries from the West were cut off, as was most contact with Church leadership. Manuals had to be smuggled across the ever-tightening border or exchanged with mission presidents limited to visits at the internation ally famous Leipzig Fair.

The Leipzig Fair, a traditional industrial and commercial exhibition held in the spring of each year, usually in March, enjoyed a long history. For decades, perhaps centuries, the city had invited business men and visitors to this display of local and national products. In order to promote international trade and the purchase of their goods, GDR leaders, even in the early years, relaxed restrictions, if only for a time, so more visitors and buyers would come. It was also a time of celebration for GDR citizens. Church leaders in both the GDR and USA utilized the event to schedule conferences where General Authorities could more easily attend. For Gerd Skibbe and most other Saints, it was a time of spiritual uplift, encouragement, and rejoicing. Aware already before 1961 that they were living in a “cage,” he treasured the visits of Henry D. Moyle, Marion G. Romney, Theodore M. Burton, Thomas S. Monson, Percy Fetzer, Joel Tate, and others who visited them. “It was a time when we felt very blessed as the Holy Ghost comforted us” (Skibbe 28 April 1992, 6).

Donald Q. Cannon, a missionary in East Germany in the late 1950s, visited the Leipzig Conference in 1959. Meetings, he reported, were held in a dilapidated hall with armed GDR soldiers at the back of the room. Speakers were told to say nothing about America. Although the atmosphere was tense, there was a great closeness among the members (Cannon 1990).

Some Saints continued to escape, but the process became even more dangerous and problematic. Escapes ensured repercussions for the faithful who remained.

Life for GDR Mormons was not made easier by the militantly anti-Communist McCarthy era in the U.S. or, especially, by the vigorous Mormon anti-Communist rhetoric coming out of both Salt Lake City and Washington. Walter Krause remembers how the anti-Communist speeches of President David O. McKay and Elder Ezra Taft Benson were monitored in East Berlin. Police and government officials fattened their files with speech after speech that stigmatized “godless Communism” as the incarnation of evil (Krause 1974). Still, for the Krauses and especially for Gerd Skibbe and most East German Saints, what the prophet and the apostle were saying was a “pleasing clarification” (Wohltuende Klarstellung) of what Latter-day Saints really believed. It was, to them, the “word of the Lord for our day” and constituted a “moral necessity” to speak out against the evil of Communism and to thereby

counteract one of its most powerful tools: to force people to remain quiet out of consideration for others. At the same time, Latter-day Saints repeatedly asked themselves: Will this [what I say or do] hurt my children? Will it compromise my brothers and sisters [in the Gospel]? Does it endanger the Church? For these reasons among some members there was a certain rejection (Ablehnung) of the anti-Communist expressions of General Authorities. (Skibbe 1992, 3)

For Saints both in and outside the GDR, accommodation between the two world views seemed impossible. Both would have to wait for God to change the system.

The Berlin Wall with its stretched barbed-wire fence, its guard towers, mine fields, dogs, and trip-wire shooting devices along hundreds of miles stopped the demographic hemorrhaging. Between 1949 and 1961 some 2.7 million East Germans had fled to the West—including some Latter-day Saints (Der Fischer 1990, 111). But it was not simply the numbers but the type of people who were leaving—the young, educated, and productive just beginning their careers—which demanded such drastic measures.

1958–68

Most Latter-day Saints were largely and intentionally uninvolved in political matters, although the Wall created a new and depressing condition for all. The safety valve had been removed; they now had to stay and come to some kind of terms with the new order. Some Latter day Saints loosened, or even broke, their ties to the Church; Communist society forced this kind of either/or choice. If, for example, a young person wished to study at the university, if an individual hoped to find a better job, if married couples were to have some hope for getting an apartment or even a car sooner, they often found it necessary to make some kind of peace with this nearly omnipotent order. Others had difficulty finding suitable LDS marriage partners—especially with the declining numbers as some drifted away or lost faith in the gospel and few new members were converted. During the fifties, only one missionary tract was available, and copies of the Book of Mormon were passed around so much that they looked soiled and embarrassed the members.

There were, indeed, many reasons why, especially after 1961, the East German Saints’ attachment to the Church might be loosened or cut. Wisely, Church leaders usually put these memberships at the back of the file to await a better and more just day. On a visit to Dresden in the late 1970s, I was shown membership records listed as “de-activated.”

But, like the pioneer Saints in Nauvoo, the large majority remained faithful. They chose the Church, and it became their life. These Saints, cut off from the body of the Church, came to rely heavily on each other, on the scriptures, and upon God. They became a large, extended family or clan, with considerable intermarriage among prominent families and leaders, both men and women, who served long terms—some said too long—in their branches, districts, and organizations. These were people of deep faith, devotion, and commitment. The Church, its preservation, and the retention of family members within the gospel net became the focal points of their lives. They nurtured one another’s faith in God and in his servants—in whom they had implicit trust. These members treasured the occasional visits of such good friends as mission presidents Joel Tate and Percy Fetzer; in the darker days of the fifties and sixties, such visits were the continuing evidence of ties with the main body of the Church.

By 1966 concern was mounting among GDR Church leaders about their long-term prospects. There were so many aging members and so few new ones coming in. Some full-time missionaries served there until 1961 when the last group was condemned by the Communist press in Saxony for being “lazy” and not taking “regular jobs.” One of these missionaries even spent some time in jail. Thus, from then on the work had to be done by members. Between 1959 and 1967, there were only 182 convert baptisms in the entire mission and only 251 babies blessed. In 1966 the mission did receive 2,000 hymnbooks and 500 triple combinations, but many members were anxious to have other helps such as Family Home Evening Manuals. As for priesthood leadership, in 1967, there were 418 elders organized into six quorums; this constituted one elder (there were no other Melchizedek priesthood holders) for every eleven members (MH).

Throughout this period of enforced separation, the Church’s most important leader in the GDR was Henry Burkhart, a full-time Church official who became the mission president and later the first Freiberg Temple president. Burkhart literally lived his life in service to his fellow East German Saints and the Church, meeting and interceding with government authorities, answering questions, pleading the Church’s case, and accounting to government interrogators both for the leaders abroad and the Saints at home. His strong and faithful counselors, Walter Krause and Gottfried Richter helped him tend the flock and hold back the wolves during those precarious times.

1969-78

The seventies brought the beginnings of a slight thaw in government relations with all denominations, including the Mormons. Although as early as 1960, party boss Walter Ulbricht had announced an end to the party’s strong anti-church campaign by declaring that “Christianity and the humanistic goals of Socialism are not antithetical,” virtually no Christian in the GDR believed him. Little changed during the sixties (Zimmerman et al. 1985, 721-22). Un fortunately, it took a very long time for this more tolerant official attitude to percolate down into the entrenched and indoctrinated party and government apparatus. Discrimination against Christians in education, work, and housing continued on the regional and local levels to the end of the regime. Still, with the publication of the new constitution in 1968, Christians seemed more inclined to cooperate with the state and to take a position labeled “critical solidarity” with the government (Zimmerman et al. 1985, 722). One visible sign of this slight improvement was that in 1976, for the first time in twenty years, the government permitted the building of churches in some newer housing developments. At the same time, government leaders decided that churches strengthened families and trained people to be law-abiding citizens, an attitude that later redounded to the benefit of the Mormons.

The lessening antagonism toward Christianity was generously reciprocated by the Mormon community and the larger Church. While many GDR Saints detested the Communist system, most understood the need to get along with authorities in the spirit of accommodation with different political systems promoted by the twelfth Article of Faith. Some even thought it important to recognize the social benefits that the Communist order had brought.

In the late sixties, Elder Thomas S. Monson of the Council of Twelve was assigned to Europe and began his special ministry among the GDR Saints. Like the Jesuit Peter Canisius of Counter-Reformation Days, he embraced the role of “apostle to the Germans.” Monson’s interest and familiarity with German history and culture as well as an obvious and reciprocated affection for the people won him a special place in the hearts of many GDR members, particularly as he began to understand the “system” and to see how, working within it, the needs of both the Saints and the Church could best be served. Elder Monson’s many public addresses clearly indicate that he was impressed by the GDR Saints’ faith and devotion and wanted desperately to serve them and the Church in that unique setting. He became their special shepherd and advocate.

Elder Monson was not the only Church authority interested in the GDR Saints. At a Munich regional conference in 1972, President Harold B. Lee may have disappointed some of them—including the few who had been permitted by the government to attend—by reaf firming the earlier Church position counseling them to return to their homes. The GDR, he said, was where God wanted them to be. This counsel, along with the already established policy of compliance with the regime, continued to build credibility and trust for Mormons at the highest level of SED leadership.

Policy and leadership changes within the Church in the 1970s eventually resulted in significant changes for Latter-day Saints in the GDR. Let me briefly mention a few of them. The doors of the “cage” began to open slightly as GDR Mormon leaders were permitted to regularly spend a week or two in Salt Lake City during general conference. During these visits, conditions and problems could be more fully, completely, and privately discussed than had been possible in frequent but limited parking lot conversations in the GDR. Still, the police checked and interrogated these visitors carefully upon their return and probably also monitored their activities in the United States. Walter Krause, for one, was always amazed at what police authorities knew about his travels after visits to general conference.

In 1973, for example, he had been ordained a patriarch during his first visit to Salt Lake City. This was the first of many small steps to bring the “fullness of the blessings of membership to more deserving, but second-class Saints.” Only a small fraction of GDR Saints had received patriarchal blessings from former mission president Percy Fetzer on his, by then, infrequent visits, and prior to the building of the Wall in 1961, only 250 Saints—almost all retirees—had been to the temple. Thus Walter Krause’s ordination enabled him to bring for the first time to the larger GDR Church membership the blessing, direction, and comfort many Saints hungered for. Through his ministry, eventually over 1600 Saints gained reassurance and direction for their lives.

Two years later in 1975, the same year the Helsinki Final Act for Human Rights was passed and signed by the GDR government, Elder Monson rededicated the land for the preaching of the gospel and promised German members all of the blessings of the Church, including the blessing of the temple, something that weighed heavily on the minds and hearts of an aging Church population. Those in attendance that day were convinced that this dedication and promise found divine approval both at the moment and thereafter. For them, God had spoken; they would now work and wait to bring about the fulfillment of the dedication promises (E. Krause 1991). For many of them, including Walter Krause, things began to get steadily better. Government authorities began to treat them with more respect, and there were signs of improvement in what little missionary work they could do. Looking back, it even seemed to them that this was the beginning of the revolution that God was bringing about in his own way (Krause 1990).

Other events also boded well: Mormon anti-Communist rhetoric ceased abruptly in the early seventies after the death of David O. McKay. Spencer W. Kimball, a man with little interest in politics and a consuming passion for moving the Church forward worldwide, became president in 1972. Very early in his presidency, Kimball spoke favor ably of what Communism had brought to China and, accompanied by his assistant, David M. Kennedy, traveled to Poland in 1977 to dedicate that Communist country for the preaching of the gospel. Poland was now opened to the Church. On his return, he reassured members in the GDR gathered in Dresden of his continuing love and interest.

Kimball’s approach was revolutionary in ways that would affect the GDR. For example, he did not advocate waiting for some divine overthrow of Communist power, wherever it existed, before attempting to begin missionary or other Church work. Church representatives were, instead, to work to obtain whatever concessions they could from governments to allow proselyting, to permit GDR citizens to attend the temple more easily, and to carry out more fully the Church’s spiritual mission. He defined the political realm, which interested the Church little, very broadly and to that end encouraged Mormon leaders in the GDR to develop a better relationship with government authorities.

He also sought to multiply the number of temples throughout the world on the principle that they need not be monumental in size. If, in different parts of the world, people could seldom afford to travel to a temple, perhaps the Church could take the temples to the people. All of these changes found resonance in the GDR.

1978–89

In March 1978, SED leader Erich Honecker announced a considerable improvement in government relationships with all churches, especially the majority Protestants. Henceforth, the government would more fully recognize the “positive role of the churches in socialism” and their right to “autonomous cooperation” in the achievement of “deeply humanitarian goals.” In addition, all citizens were to have an “equal opportunity” in society regardless of religious affiliation. In short, religious people in the GDR were to have a more amiable existence, even, Honecker promised, on the local level where tension was often greatest (Zimmerman et al. 1985, 724-25).

But all was not sweetness and light. The eighties brought a new and different source of tension arising from the militant pacifism of the emerging Peace Movement, whose motto was transforming “Swords into Plowshares.” This Peace Movement, developing over the years, provided much of the basis, inspiration, and organization for the rallying forces which later in 1989 bloodlessly and magnificently toppled the rotten Communist order. Paradoxically, the Movement improved government relations with GDR Mormons, who lacked the pacifist tradition as well as any heritage of cooperation with other German churches. That, combined with resolute Mormon adherence to the twelfth Article of Faith, and a changed awareness that Mormons were among the most productive and wholesome citizens, led to the Church being identified as among those groups who were more supportive of the existing order. Thus, ironically, one of the churches which had in the beginning of Communist rule been singled out for its denunciations of Communism was now looked to as a source of support. It was a dubious honor.

In the 1980s Mormons also began to see the fruits of their earlier diplomatic labors. Besieged by hundreds of requests from older Saints to travel to the temple in Switzerland and unwilling and unable to explain what was viewed by religious and other groups as preferential treatment, the government now, with greater trust, inquired why the Church did not build its own temple in the GDR. Documents detailing the temple-building and its cost are not yet all available; but by 1985 the temple had been dedicated, and thousands of GDR Mor mons were able to attend for the first time (Backman 1987). Over 80,000 GDR citizens attended an open house prior to dedication and marveled that it was even possible to get materials for, much less finance, such a beautiful building. They assumed—incorrectly—that all the money had come from the United States. Stylistically the temple blended well with surrounding buildings with a grace missing in other modern temples. For most devout Latter-day Saints, Elder Monson’s prophetic promise a decade earlier had been fulfilled.

But there was to be more. In rapid succession, new chapels were built in Dresden, Leipzig, and Zwickau, with plans on the books for nine or ten more. In 1984 Bishop Walter Müller proudly showed our visiting BYU group where the new Leipzig branch would be built. Five years later, in August 1989, we actually worshipped with the Saints in their beautiful new building. The visible presence of the Mormons had changed dramatically, as if overnight.

The apogee of this transformed relationship was reached both symbolically and actually on 28 October 1988 at a meeting of President Monson and his associates with Erich Honecker and members of the Politburo. As reported the following day in the official party newspaper, Neues Deutschland, Honecker repeated his post-1978 equal opportunity policy toward churches and lauded the Mormons for their work ethic, their strong families, and the moral development of their youth. The GDR, he said, could certainly use people like the Mormons (“Begegnung” 1988, 1).

In response, President Monson mentioned how the Church and state could cooperate in improving the environment and the lives of both individuals and nations, “even when they may not agree on everything.” Monson and Burkhart both praised the “balanced” policy of the state toward all churches, not just the larger ones, a hint at the appreciation Mormons felt toward the government for putting their long-time nemeses in their place (“Begegnung” 1988).

The Church benefitted considerably from this encounter. It appears that Honecker granted its requests, including the right to do missionary work again for the first time since 1961, an extremely urgent matter given the declining and aging membership. New members were desperately needed. In April 1989, Garold and Norma David, both professors at BYU, were among the first Western missionaries to open the new mission in Dresden (1991, 22-27).

Equally important was a further concession that young GDR Latter day Saint men and women would be permitted to leave the GDR to serve as missionaries. The first group of ten arrived in Salt Lake City on Memorial Day 1989 and were scattered throughout the U.S., Canada, and Latin America as that part of the Church was integrated into the worldwide missionary program.

In late August 1989 I was participating in a BYU Vienna Study Abroad Group. We visited the GDR Saints, totally unaware of what revolutionary changes the next few months would bring. GDR Saints were euphoric about the missionaries and even more ecstatic about the over 200 converts they had gained in just a few months. Spirits were higher than they had been at any time since 1969.

By late October 1989, Honecker had already received the “kiss of death” from Mikhail Gorbachev in Berlin. Two of our BYU students, Amy Goeckeritz and Toni Lambert, had received permission to spend the traditional “Live-In” week (a time for students to spend with a family speaking their studied language). Upon their return to Vienna, they told unbelievable tales of going with their “families” to the Leipzig demonstrations on Monday evenings for Home Evening. They described the GDR Saints’ guarded but hopeful optimism about what all of this fervor might bring. According to Edith Krause, GDR Saints not only participated in the demonstrations, but several voted “with their feet,” joining the throngs who left the GDR for the West and thus put pressure on the regime and attracted worldwide attention to conditions in the GDR (1990).

Other Saints, such as Andreas and Ingrid Ortlieb living further north in Schwerin, regretted that they, on the counsel of their stake president, had not participated in the demonstrations that eventually brought the hated government down. Mormons, on the whole, played only a direct minor role, participating individually, not as a church, in the turn of events that eventually brought political freedom, real religious freedom, and eventually unification to Germany. Of course, over the years, Mormons had also played an indirect role by joining their prayers with others to petition God to bring about the change. In any event, as Edith Krause wrote, she, Walter, and other GDR Saints were very grateful for the more politically active role the Protestant and Catholic Churches played in the revolutions (1990).

In retrospect, some meaningful questions may be asked. For instance, how are our individual destinies tied to the divine destiny of the world? From the GDR Saints’ perspective, the Heilsgeschichte, the history of salvation, appears to be a process carried out by both God and humans, each doing what is possible and necessary to bring about the divine destiny of the world and the salvation of God’s children. Forty-five years is probably not very long in the divine scheme of things, but it seemed like an eternity for those who lived in bondage. Still, their faith was rewarded; it survived a long and bitter trial.

Their experience raises questions about continuity and change. BYU history professor Thomas Alexander recently published an informative and enlightening article on the Church’s change of perspective at the turn of the twentieth century. Shifting away from an emphasis upon political conformity and economic autarky, while discontinuing the practice of plural marriage, the Church laid greater emphasis upon its spiritual and religious mission. In this way, it accommodated itself to the United States and paved the way for its spiritual, economic, and demographic prosperity in the twentieth century (1991, 21-27). This policy seems to have served the Church well as it has reached out to other nations of the world.

Such policies, interpreted on a worldwide scale, were applied first to Hitler’s Germany and again to the German Democratic Republic. In one sense, they appeared to have worked: the Church was pre served to pursue its primary mission without surrendering its teachings, beliefs, or institutions. No Latter-day Saints were forced to deny Christ or covenants they had made. And now the tyrants have been dethroned and freedom established.

But nagging doubts remain: Has the policy of accommodation perhaps been taken too far? Is it time for a change? When, in fact, does a political issue become a moral issue, and who decides that point, both for the individual and for the Church? Should a Church with an universal spiritual mission not also serve as a universal conscience? Why is pornography a moral issue, but apparently the violation of basic human rights is not? How far should a church go in accommodating atheistic and swinish dictators—remaining silent during a Holocaust or while every inalienable freedom “which belong to all flesh” is violated—in order to preserve itself or promote its own interest? Should our Church withhold cooperation with Christian and other churches willing to put their lives on the line to bring about a people’s God given freedoms in the here and now?

Perhaps on this last matter it is time for a change; that change may, indeed, be underway. It’s time to “bury the hatchet” with churches—Christian or otherwise—and recognize that a major challenge of the twenty-first century is still to bring all to the gospel of Christ, particularly the secular and the unchurched. Perhaps the GDR experience can guide us toward cooperation in this enormous task.

Finally, and again paradoxically, the latest challenge for GDR Saints may be their most trying. It may not have been very difficult to be obedient to Church authority when tradition, history, and an authoritarian social order had trained GDR Saints to be largely quiescent. Today’s challenge, after the wall has fallen, may be the most difficult of all: to live in a free but intensely materialistic world—ironically not the materialism that Marxism promised but failed to create—but the free market economy where materialism actually holds sway. Only then will we discover if the coming generations of German Saints—both those in the East and in the West—will, in fact, fulfill Elder Spencer W. Kimball’s prophecy given 22 August 1955 in Berlin:

‘Do you see this glorious vision? Do you see what can happen if we stay here and do our part unselfishlessly to build up this great kingdom?’ He prophesied that temples would be built in Europe in great numbers. He foresaw the day when Latter-day Saints would partake of the same high esteem in the eyes of the Ger man people as they do in the eyes of the public in general in America. He said Latter-day Saints would hold influential positions in government; would be professional men and women; should be school teachers, surgeons, lawyers—people of high esteem. He told the members it was no longer necessary for them to go across the ocean to enjoy every blessing necessary for exaltation. Every person in the audience was truly moved by this great discourse under the influence of the Holy Ghost, (in Ernst n.d., 97)

[1] In August 1989 I was visiting East Germany, and our tour guide, Johanna Koncynski, articulated this frustration when we dropped her off before driving our bus into West Berlin: “I like my country. I can’t understand why they won’t let us see the rest of the world. I’d come back. I’m tired of being locked in here.”

[2] For the degree of angst felt by everyone, including the churches and even the Evangelical Lutheran Church, see Hans-Jiirgen Roder, ” ‘Fall Stolpe’ langstein ‘Fall Kirche,’ ” Deutschland Archiv 25 (May 1992): 449-50.

[3] Even after thirty years of Communist rule, in 1977 the census showed over seven Protestants for every Catholic or sectarian, 7.9 million to 1.4 million. Over half of the population listed no religious preference (Zimmerman et al. 1985, 1:715).

[4] In 1940 Germany was in third place behind Canada (and remained there through 1960), but just barely, with 13,480 to 13,801. After 1960 Church growth elsewhere, particularly in Central and South America, left Germany in the dust (Scharffs 1970, xiv).

[5] Many GDR LDS families believed implicitly that God had called them to stay there, as Elder Ezra Taft Benson counseled them in 1946, and help build up the Church. Walter Krause remembered that after the wall went up in 1961, one brother upbraided him for having advised him to stay: “Brother Krause, I will hold this against you eternally. You counseled us to remain and endure here. Now my children will grow up in Communism, and everything will turn out wrong” (Krause 1990).

[6] According to Scharffs, 400 LDS soldiers from the East German and about 150 from the West German Mission died in World War II (1970, 116). Arthur Gaeth, former Czechoslovakian mission president commented in June 1946 how “few young men” there were in the branches (Gaeth 1946).

[7] Many older GDR Saints carried with them a resentment against the dominant churches who had persecuted them in the past.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue