Articles/Essays – Volume 27, No. 4

Dust to Dust: A Mormon Folktale

The morning promised no bright sun. No blue sky. Only dust from the desert’s chalky red soil. “Lord in heaven,” Rosalinda said to herself. She stared out the window, worried about her garden. She couldn’t see what little was left of it, its struggling vines obscured by the blowing dust.

“How can I feed my children if this keeps up?” She folded her arms, slumped her shoulders, and for a brief second filled an imaginary cornucopia with squash, tomatoes, onions, and grapes from the fertile earth of her mind. Then the picture disintegrated into a dusty blur.

Everything around her was filling with dust—the cracks and seams of her adobe house, the braided rug, the plates on the cupboard. Touching her face, she felt sand in the crevice of her nose. If this kept up, dust would soon fill her mouth, her eyes, her ears, and Rosalinda and her children would be buried just like Kenneth.

She closed her eyes and pressed her fingers to her lips. Dust to dust, the Bible says. God made Adam out of dust. He breathed life into his nostrils.

Impulsively, she rushed to the only door of her house and cracked it slightly. “Kenneth, is that you blowing around out there?” she whispered. The storm was too fierce for her to wait for an answer, so she quickly pushed the door closed, unlaced, stepped out of her heavy shoes, and tip toed back to the window where she felt the rush of air through the chinks. It lifted the hair on her arms.

Suddenly, she sensed movement. The storm’s chaos was cloaking something out there. She bit the tip of her finger. “No harm, please Lord.”

Rosalinda hurried to the bedroom to see if Chad and Peter were safe. Her boys were still tucked in their small bed and protected by sleep. She tiptoed back to Jessica curled around a crocheted pillow on the settee, one leg dangling over the cushion’s edge. Tracing the upper curve of her daughter’s lip, velvet as the roses she’d have grown if the hard clay outside could have nourished them. Rosalinda wished once again she hadn’t left England. Why had she rushed to the State of Deseret for the Second Coming? Then she hurried back to the window, just in time to witness a sudden break in the storm. “White horses!” she said too loudly, then covered her mouth with her hand. She mustn’t wake the children. She strained to see through the mottled glass. Behind white horses bowing their heads against the wind, there was a golden carriage. But then dust blocked her line of sight again.

“There’s no such thing as a coach and four in this part of the world,” she muttered, nevertheless leaning against the sill and waiting for another lull in the storm.

So much dust filled the air that it truly did seem as if the decomposed dead were blowing about, waiting for God to breathe life back into their nostrils. Dust to dust, the Bible said. Maybe, Rosalinda thought, some of it might be her Kenneth, her dear, God-loving husband who’d spurred his horse into a thunderstorm when he should have been singing songs and eating popped corn with her and the children at the fireplace. But Ken neth, the good shepherd, rode after two lambs. When the lightning hit, it pierced his shoulder, his saddle, his horse Midnight, and exploded a nearby juniper into flames. When Rosalinda saw the fire through the drizzling rain, she somehow knew that Kenneth and Midnight’s spirits had already flown to heaven. She found their empty bodies next to the saddle. It was burned clean through with the shape of a jagged star.

The storm outside was thickening to an angry yellow. “What’s out there?” She hugged her shoulders tightly and leaned one way, then another, hoping for something besides dust. “What misfortune now, God? Isn’t my trial sufficient for you?”

Immediately, she cupped her hand over her mouth, trying to catch her words before they ascended to heaven to offend God, but before she could retract anything she felt the power already in the room. It burned through her like the shape of a burning star in her heart, like God’s finger parting clouds so abruptly. She shivered, pulled her shawl from the back of her rocking chair and wrapped it around her goose flesh-covered arms.

“But Kenneth was a good man, God,” she said, as if to apologize. “He loved to quote scripture, especially ‘A merry heart doeth good like unto medicine.’ Heaven isn’t a lonely place, God. You’re there. If you are love, like the scriptures say, then you don’t need Kenneth, do you? In fact, you could breathe life back into his nostrils if you wanted.”

The dust darkened to a deep orange and blew more wildly than she’d ever seen. But what if this storm was Kenneth tiring of the Celestial Kingdom and impatient for her love? Maybe he was being sieved through the window in particles, a little bit at a time. Back to say, “Hello, Rosalinda. I miss you. I love you.” Back to take her in his arms and whirl her in a fancy waltz as he used to do after a hard day of work.

“Daddy,” Jessica said from the depths of her sleep.

“Oh, don’t wake yet, child.”

Jessica stretched her arms as if she were ready to wake, then tucked them back into her chest. Rosalinda sighed relief. She wanted to know what was outside before she answered anyone’s questions. She wanted one clean look at the road.

And suddenly, there it was—a large gap of blue sky. In it she saw a coachman with gold braid on his sleeves, two golden post lamps, gold leaf carving on the high sides of the carriage, and gold ornaments on the horses’ reins. As the returning dust obliterated her brief glimpse of the impossible, she thought of something she hadn’t remembered in a long time. She rushed to her desk, pushed its roll top back, and pulled out her sewing basket. Lifting the lid, she pressed her fingers against the place in the lining where her own gold was hidden. When she touched the fabric, its coldness and unearthly smoothness made her tremble. It was a piece of the same satin that lined Kenneth’s coffin. Rosalinda had coaxed a yard of it from the undertaker’s assistant.

The night before Kenneth was buried, she stroked this same cloth, trying to feel something for that strange man in that box who was so unlike the man she’d known, so immaculately still and immovable. Rubbing the fabric between her fingers, she’d kissed his forehead and closed the lid.

After the funeral, when her friends left for home, she used the satin to line her sewing basket. She’d sewn a gold coin inside, the one her father pressed into her hand when she set sail for America. This piece of precious metal meant she had something between herself and nothing.

She pushed the basket back to the dark corner of the desk and hurried back to the window where she gathered folds of muslin curtains between her fingers. The door of the carriage seemed to be opening, unsteady against the force of the wind. She thought she could see the shape of one long black boot hesitating at the foot rest, another touching the ground, a tall man standing in the road.

At first, he seemed in no hurry. Then he walked directly toward her door. Rosalinda held her breath and waited for his knock, though she wasn’t sure she wanted to hear one. Was this a ghost? A messenger from God? What else could it be? Then she heard knuckles against wood. Five raps. Slowly, as if the air were lead and resistant to her curiosity, she opened the door a half inch and peeked at the man on the other side.

He was tall with a sensitive, elongated nose. His face seemed made of ageless skin supported by the finest bones. Rosalinda could only stare through the narrow crack, her lips slightly parted. He wore white breeches, a blue velvet long coat, satin ruffles under his chin, a barrister’s wig—all coated with a thin red powder from the storm. He held a white lily, his right hand protecting its petals. “I come as your servant,” the man said, bowing slightly.

Rosalinda shuddered, remembering the last time she’d seen a lily—at Kenneth’s funeral. She scrutinized the man’s slightly gray fingers wrapped around the lily’s stem, and his face, which seemed neither young nor old.

“Don’t be afraid!” The man put out his hand to stay the door. “Savor the things of God, not of men, Rosalinda. It’s time for you to trust.” Rosalinda blanched at the sound of her name.

The man withdrew a lace handkerchief from his sleeve and covered his nose. Although his eyes watered from the irritating dust, he maintained an elegant posture and continued to protect the lily against his concave chest.

“People have told me,” he said confidentially to the thin slice of Rosalinda’s face, “a camel can go through the eye of a needle more easily than a rich man can enter God’s kingdom. Few understand poverty as the condition of being without faith. Do you believe only the poor know poverty?”

The storm blew crazily at his back, anxious to invade the house. “May I come in?” His words were muffled by the handkerchief.

“Well,” she slid her fingers down the side of the door, “I don’t think it’s a good idea.” She felt the bite of the sand on her cheeks and eyelids. “But then,” she opened the door, “it would be unkind to leave you in this storm.”

As he crossed the threshold, she became acutely aware of his majesty—the way he carried his chest and head as if they were full of air. She wished one of her children were clinging to her leg so she’d have something to hold. When Rosalinda shut out the storm, his presence seemed to grow larger and wider and fill the entire room—up to the ceiling and out to the walls.

“Would you like a drink of water?” she whispered as they stood awkwardly by the door. Without thinking, she fingered the collar of her dress where she’d embroidered her name, R-o-s-a-l-i-n-d-a, in white thread. The night after Kenneth died, she sewed the letters to remember who she was, to keep herself from losing herself. No England. No husband. “I’m whispering because my children are sleeping.”

“Water would please me greatly,” he whispered back.

“I’d offer you a soft place to sit, but my daughter Jessica’s occupying the settee. Have my rocking chair.”

“That won’t be necessary, but water would soothe my parched throat. And please, take this.” He handed her the sand-pitted flower.

“A lily,” Rosalinda said. Her cheeks blossomed the rare red of an apricot. “This is for a funeral. Is someone else going to die?”

“What about the lilies of the field, Rosalinda?”

“Fine words for you to say.” She felt a hard place growing in her throat past which she couldn’t swallow. He’d spoken her name which he couldn’t have known. “Excuse me,” she said, pressing her lips tightly against each other to hide her emotion. She rummaged in the cupboard for her only vase and a tin cup.

Tipping the water bucket, she sank a long-handled dipper into the last few inches of water. She filled the vase and the cup, careful not to spill. She slid the lily into the fluted neck, turned the flower to an angle that would suit her English gardener’s eye, and set it on the wood table. Then she handed the cup to the stranger. “How do you know my name?” she asked timidly.

“I know many things.” He drank to the bottom of the cup, handed it back to Rosalinda, and looked down at her with mournful eyes. Under his gaze, she became aware of her simple black and white checked dress, something she’d made herself, and her hurriedly plaited hair. She set the cup down, then leaned against the table’s edge and folded her arms resolutely.

“How do you know my name?” A wisp of hair fell over her eyebrow. She pushed it away. “Did someone in town tell you?”

“No one told me anything.”

“What are you doing in a remote place like this?”

“I’ve come to see you.”

Rosalinda shifted her weight from one hip to the other. He smiled. “One shouldn’t take oneself too seriously, even if you’re all alone at the edge of the world. You’re angry at God, aren’t you?”

Rosalinda turned her head to the side. “What makes you think so?”

“As I said, I know many things.”

“So what do you know if you know so much?”

“At this moment, I know there is music on the wind. Can you hear it? God is all around us.” Rosalinda squinted her eyes and tried to hear something besides the storm.

“When all else fails, I listen for music,” he said. “It’s God’s gentle breath, you know. Today, it’s a Viennese waltz.” His eyes changed from mournful to shining, as if a thousand candles reflected their light in them.

“A Viennese waltz?” She and Kenneth used to pretend they lived in a castle on windy nights when even the stars seemed as though they’d blow away. She smiled faintly, thinking of how she once fantasized Ken neth’s mud-caked boots were shiny black, that Kenneth was a captain in the Queen’s cavalry. Her visions of brass buttons and shining black boots were interrupted, however, by the persistent thought of her gold coin hidden in the sewing box. It burned oddly, like fire in her mind.

”Who are you?” Rosalinda asked, almost harsh in her insistence.

“Why do you insist on knowing who I am?”

“But where are you from?” Her tone was suddenly demanding.

“That, too, is not important.” He smiled again, such a disarming smile that Rosalinda blushed. She’d only seen the likes of this man in the water-colored pictures in her mother’s handed-down story book. Her mother wrapped it carefully and tucked it in Rosalinda’s valise just before her daughter climbed the gangplank of the steamer in Bristol.

After the long days at sea and harsh days of bouncing on a buck board wagon across the endless plains of America, Rosalinda would find a place to herself—a porthole or a stream or a tree. She’d unwrap the book carefully and open its pages as if they were made of silken spider threads. In the fading light of day, she turned to each delicate painting and listened for her mother’s voice: “This is for your dreams, Rosey Linda.”

But the storybook character standing in her house was flesh and blood. His manners were alien, especially the way he swept his fingers through the air as if they were a fan in the act of closing. He was different from her humble Kenneth, who was so close to the earth. He seemed a bit pinched in his chest and cheeks, an odd bird who, if he flew, would fly at a graceful tilt. And yet there was something about him that did remind her of her dreams.

“Surely you can hear the waltz?” he said as he put his kerchief in his vest pocket. “May I?” Before she could protest, the gentleman’s arm clasped her waist, his other arm reached for her hand, and he led her into dance. One-two-three, glide-two-three. Her cotton dress billowed as they whirled around the room to windblown strains of a waltz she couldn’t hear.

Her better sense warned her to gather her wits. She was dancing in the morning when there were practical things to be done; she was only Rosalinda with an adobe house and a withering garden; she was in a stranger’s arms. Suddenly, she was unable to lift her eyes any higher than the gathers of satin at his throat. She wished he would let her go, but his grip was firm.

One-two-three, he spun Rosalinda until she felt she would never stop spinning. She felt his closeness and smelled the traces of powder near his throat. For one small second, she relaxed and let herself spin with the assurance of his hand against her back. For a brief moment she felt her feet turn to wings and fly over the plank floor. One-two-three. She ventured a glimpse of his strong, straight nose, then the entirety of his face. She found his eyes looking back at her, staring long and hard into her soul. She felt them tunneling through her, back to the beginning of herself, back to the pre-existent Rosalinda. But then, he stopped.

“Trust not in the arm of flesh,” he said, taking both her hands and pressing them to his lips. “You must have faith that God will guide and protect you.”

Embarrassed by the sudden beginning and end of the dance, Rosalinda tried to find a place for her hands. One brushed her throat, then slid between her breasts to clasp the other hand. Shaking her head in confusion, she sat in the rocking chair and listened to the wind. Only the wind was real, her shriveling garden, her children who would wake any minute. She touched the dust on her cheeks again, fine as talcum. “Why are you here?”

“You must embark on a journey of faith with me,” the stranger said, dropping his head forward in what seemed like humility, Rosalinda wasn’t sure. “I’ve come upon hard times, I could say.” Then he looked up. His gaze was direct.

She swallowed, the image of the gold coin penetrating her thoughts again.

“‘Do this unto the least of these, your servants,'” she heard him say. She struggled to hide her astonishment and to keep back the words ready to rush off her tongue: You’re in no way the least of anything! You’re a man with a fine carriage and satin breeches.

“Anything you have will help me.” His eyes had no lack of dignity. “I come as a supplicant. I have nothing but my faith, which I’ve brought to you.”

“But what about the horses and the … ”

“I own nothing,” he said so firmly Rosalinda suddenly believed him. His eyes changed weather, now like a deep lake with the wind whipping its surface.

“I have nothing to give,” she said, seeing the gold coin even more clearly in her mind. Its image throbbed as if it were part of her heartbeat.

“Nothing?” the man said, a slight look of curiosity in his eyes, as if he could read her mind and see the coin living inside her.

“Nothing I can spare,” she said as she surveyed the room to see if her children were waking. If a child would only say, “I’m hungry, Mama,” she could be strong and push the gold coin deep inside her thoughts instead of so close to the surface where the man could see.

“Humans possess nothing,” he said. “Everything is a gift. Where is your faith in this bounty?”

“But what about my children?”

“‘Whosoever shall lose his life for me, the same shall save it.'” His eyes shifted character again. He looked to her like Moses staring into the burning bush.

“But I’m alone.”

“What shall you give to find your soul again?” He seemed taller than before, as if he spoke to her from a raised platform.

The gold coin seared the inside of her head. She put the flat of her hand to her forehead to see if she had a fever, but felt only the insistence of something wanting out. She knew she couldn’t hide the coin from the man any longer.

As she walked across the braided rug, she thought of her safety. The food for hard times. But this was what the coin was for. This moment. She knew.

She lifted the lid on the desk and slowly pulled the sewing box into the dingy morning light. She felt for the hard coin in its secret place underneath the lining and carefully pulled a thread until it snapped, unravelled, and the gold was in her hand. “Here,” she said.

“You will be blessed,” he said, the pinched quality leaving his cheeks, his breathing more relaxed. He slipped the coin into his handkerchief. “All of us want from time to time, and because you have given from your want, God’s face will shine on you.” Smiling broadly, the man bowed to Rosalinda, bending one knee deeply, his hat brushing the floor. “A queen among women,” he said and turned to open the door to the dust that swirled around his head, his ankles, his velvet coat.

As she watched, Rosalinda could barely see the man climb into the carriage, the coachman whip the horses, the post lamps shine in the dense storm. The sand stung her face and whipped her hair.

As she closed the door, she stepped into her work boots, laced them securely, and leaned against the wall. She rearranged her turbulent head of hair and pinned it away from her eyes. Her hand fell from her hair to her neck and rested on the collar of her black and white checked dress.

Very slowly, she became aware of the raised stitching on her collar, the embroidered letters. The white thread on the black and white checked collar. Of course. That’s how the man knew her name. He was no ghost or heavenly messenger.

Rosalinda, she cried inwardly. She slapped both hands on her cheeks to waken herself from this bad dream. With one of her heavy boots, she stamped the floor twice.

“What a fool!” Tears careened through the dust on her cheeks. “So easily taken by skewed chapter and verse and a silver tongue.” The dust in the room rose as Rosalinda’s angry foot struck the floor, slowly settled back on her shoulders, her hair, her clothes. Everything was only dust. Nothing more. Nothing less. Why was she subject to her foolish hopes when she should just accept that dust was dust?

“Mama,” Jessica sat up and stretched like a cat after a long sleep. “What’s wrong with you?”

“Your mother’s a fool.” Rosalinda paced back and forth, the boards sounding with her heavy step. “When we’re close to starving, I give everything to the rich who get richer while the poor get poorer.”

Jessica spread her arms like wings over the back of the settee as Rosalinda blotted the tears in her eyes with the heels of her hands. “Why has he forsaken me, Jessica? Why don’t I hear answers to my prayers?” She grabbed her daughter’s hands too tightly, then sank to her knees and fell against the settee’s cushion.

“I dreamt about Daddy,” Jessica said, tucking her mother’s hair over her ears and caressing her cheek. “He was walking in a field of white flowers. A bird sat on his shoulder. He was quoting scripture.”

“What flowers are you talking about?”

“My dream,” Jessica said.

“White flowers?” Rosalinda said, looking up sharply at Jessica’s face. “What kind of flowers?”

“Just white ones.”

“Like that?” Rosalinda pointed to the lily in the vase. Her voice was unsteady.

“Don’t look at me that way. You’re scaring me.”

“Remember,” Rosalinda begged. “Please try to remember.” She rolled onto her hip and pushed herself to her feet. She rushed to the vase. The flower was scarred, barely a lily. “Like this, Jessica?”

Jessica shrugged her shoulders as Rosalinda returned with the flower in her hands.

But suddenly, Rosalinda didn’t need an answer. She looked into the lily’s face, at the scars on the surface, its long throat scattered with bits of dried stamen, the curling of the petals, the brittleness just before the crumbling into dust. But dust could be breathed back to life. Made into something new.

Rosalinda started as if someone had called her. She jumped to her feet and rushed to the window, her chin raised in hope.

“Listen to the wind,” she said.

Jessica’s face was a puzzle of disbelief.

“Can’t you hear him? He’s in the dust.” Rosalinda wrapped herself in her arms and rocked her shoulders. She rolled the stem of the lily back and forth across her upper arm with the flat of her hand. There was a strange play of light in the room.

“What, Mama?” Jessica said.

Rosalinda held the lily as if it were a prayer. “‘They toil not, neither do they spin. Take no thought for the morrow.'” She ran to the door, opened it, and shouted into the wind. “I hear you, Kenneth. I hear you. I’ll try not to be angry or afraid, I promise you, Kenneth. I promise you, God.”

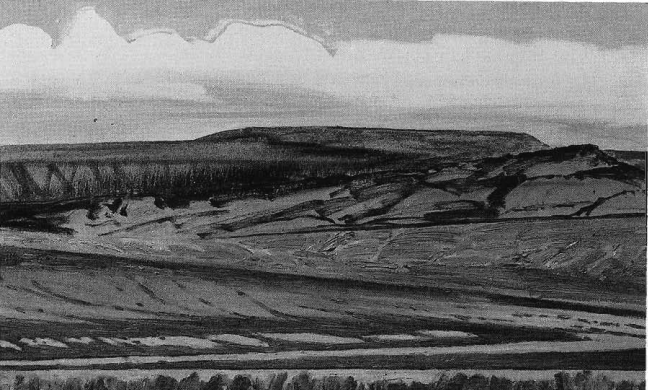

As Rosalinda’s last words died in the frame of the open doorway, the wind ceased. The storm that had been raging for hours stopped as though it never happened. For the first time all day, she saw the sun and the red hills against the bold blue sky.

She ran out on the road to check for signs of the carriage. There were none. Dust covered any track ever made in front of her house—coyote, fox, horse, even carriage wheel.

As she gazed across the trackless sand, she clasped her hands and the flower tightly in front of her, so tight that the seed of faith trapped inside would never, ever escape. The dust-covered vines of the garden rattled like gourds in a final gasp of wind, making music for this moment.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue