Articles/Essays – Volume 11, No. 1

Gambit in the Throbs of a Ten-Year-Old Swamp: Confessions of a Dialogue Intern

How does an English graduate student who wants a visit to the East Coast, instruction in the American political system and an introduction into the Mormon publishing world satisfy these three ambitions in one two-month gambit? Simple—she packs herself off to Washington D.C. on the BYU Washington Seminar program, spends Thursday evenings and Fridays learning about government from government officials, and works Monday through Thursday as the first official intern for Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. My two-month stay provided me with more than eight units of academic credit.

Memories of my internship are merged with memories of the weather. I didn’t believe the descriptions I had heard of Washington’s summers—no one had effectively conveyed the strange sensation of living in a swamp three hundred million years ago (a phrase I lifted happily from an apropos Smithsonian exhibit). I blessed Mary Bradford’s air-conditioning every time I entered her home and descended (after having revived myself with three cups of water at her kitchen table) to the basement office of the journal. I spent a lot of time in that basement, answering an endlessly ringing phone, reading back files, typing, keeping abreast of submissions, proofreading galleys and leaving my critical gems in the folders of manuscripts under consideration.

The pervasiveness of my weather memories surprises me now but may help to explain, though not entirely, the feeling of loneliness I associate with my internship. Occasionally for several days running I was the only staff member working there, sometimes neglected, sometimes with too little work to keep me involved and productive. Perhaps the ever-lurking weather intensified the oppression I sometimes felt.

There were other moments of reckoning. I was taken aback when a fellow excitedly inferred from my employment with Dialogue that I was a “liberal Mormon,” a term I had earlier used myself as a tool of censure. I felt acute disillusion when some dear friends overseas refused to submit articles for the upcoming international issue—on principle. And I felt frustrated noting that my major accomplishment for the week had been to finagle a car and take a pile of backed-up manuscripts to the photocopy center: when a writer fails to submit his manuscript in triplicate, a staff member must have two or more copies made before the manuscript can be mailed to board members for critiques.

But there was excitement, too, not the least of which was the arrival of the daily mail. The Dialogue office anchors one end of countless hotlines leading to points all over the country. Who could pass up the chance to read letters from people as diverse as Dialogue contributors, editors and readers? Through reading the daily mail—as well as reading widely in the magazine—my glimpse into the Mormon publishing world became characterized with some very real, very interesting people.

There was also excitement the day boxes of the “media” issue arrived—and staff members scattered throughout Washington D.C.’s environs gravitated quickly to Mary’s basement. Even I, who had not worked on the issue, felt the curious pleasure of seeing ideas turned into print. Excitement throbbed, too, when the galleys arrived for the Book of Mormon issue.

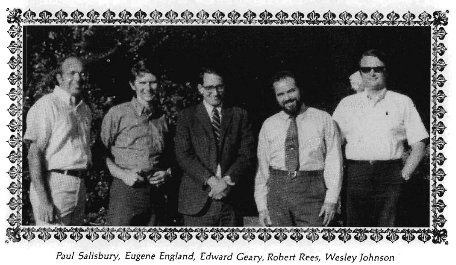

And I felt respect—respect for Lester Bush in his willingness to track the Spalding manuscript story in all its convolutions, aiming always, in his thoroughly scholarly fashion, at the truth; respect for the complimentary professional skills of Mary Bradford and Alice Pottmyer; respect for a manuscript submission process which not only selects quality writing for publication, but also makes the submission process itself learning experience (manuscripts are returned with individual comments, not a form letter); and respect for an editorial board whose time and energy are devoured by this process, but who receive no tangible compensation for their service. Certainly, were the process abandoned of securing three individual critiques on each submission, manuscripts could be returned to writers far more speedily. But the board is committed to helping writers improve. Though critiques may be inaccurate as well as divergent, at least the writer knows how his work has been received. A form letter contains no such individual feedback.

However, the experience which I recall as the most satisfying occurred at the typewriter downstairs. I had been delighted when Mary assigned me to solicit articles, essays, stories, poetry and artwork for a future issue of international theme. Largely owing to my own travels, I am committed to recognition of overseas Mormons, persons out of the mainstream of American Mormon intellectual life and whose achievements are, therefore, often overlooked. Now as never before ours is an international church; the Gospel is not more true in American Fork than it is in Thailand, though perhaps in Thailand we can see its principles more freshly, vividly for its relief against a foreign surface. Writing letters to my overseas contacts and others who had previously expressed interest in the project carried for me the sweet satisfaction of doing something about something I believe in.

It was rewarding to know that in Mary’s basement my ideas and abilities were trusted. This was a professional, not an academic experience. Reading manuscript submissions from some of my own professors, manuscripts not always selected for publication, faded the distinction for me between teacher and student. For example, Mary asked me to critique the poetry of a professor who had been less than thrilled in my own writing ability. And there was heady satisfaction in using whatever critical acumen I have developed as an English major, not on literature of past centuries already acknowledged as great, but on literature being written now by very real, very interesting people. How revealing to learn the process whereby one submission is rejected while another heartier piece is embodied in print and launched on a career of its own! The value of cooperative education lies, of course, in just such realizations as these.

I got to know Dialogue in Mary’s basement last summer. Spot-checking the journal’s new ten-year index and filling orders for back issues were good ways to acquaint myself with individual issues. Later, when I arrived home in California at the end of my internship, I spread my newly acquired set of Dialogue back issues on our dining room table. The effect was dramatic. I could not deny the pride I felt in having contributed (even when simply herding correspondence, files, telephone messages and Mary’s three children) to the general body of talent and skill which has produced ten years of artistic, scholarly journals. Not every article within those pages appeals to me; but I will remember my joy last summer in discovering the poetry of Margaret Munk, Sherwin Howard and Clifton Jolley. And I will remember reading Eugene England’s “Great Books or True Religion,” Mary Bradford’s personal essays, Thomas Schwartz’ essay on Clinton Larson’s poetry and Bruce Jorgensen’s appraisal of the verse of Carol Lynn Pearson.

I joined the Church in 1969 and started college as an English major two months later. I have been wondering ever since what role good writing should play in the Church. After all, I have met at least one Church member who circumspectly removed all novels from his bookshelves because he didn’t feel the Savior would approve. I have sat through countless discussions in BYU English classes on the subject of Mormon literature, sometimes despairing at the futility of theorizing rather than writing. And I became familiar last summer with one journal’s attempt to perpetuate not only quality writing in a spectrum of disciplines, but also quality format. My experience as a dialogue intern was sometimes frustrating and lonely, is tied to the oppressiveness of a Washington summer, and though I cannot always endorse everything Dialogue does, nevertheless, before I returned from my two month sojourn to the crisp Utah air, I left ten dollars (student-rate) in the basement and became a subscriber to Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought—a project which carries for many the sweet satisfaction of doing something about something they believe in. I have been defending it in office and cafeteria discussions ever since.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue