Articles/Essays – Volume 24, No. 1

I Married a Mormon and Lived to Tell This Tale: East Meets West

I have enthusiastically accepted the invitation to share my experiences as a “cultural Jew” married to a “cultural Mormon.” Kenneth and I have been married almost twenty-three years. I have lived in Salt Lake City since 1971 and before that for nine months when we were first married.

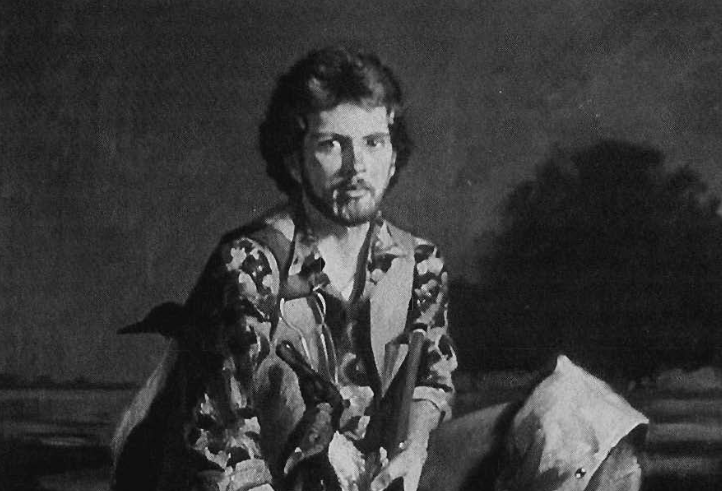

I met Ken while we were both working for the New York City Youth Board, a social service organization that worked with ghetto dwelling gang members and their families. Ken had come to New York as a social worker after graduating from the University of Utah. He was the first Latter-day Saint I had ever met. Back then in 1966, I thought Mormons still dressed in somber suits and long skirts and rode in buggies. This is despite the fact that I was a graduate of an academically challenging university and had traveled to Europe and Israel. I liked Ken before I fell in love with him, though I confess we had been acquainted only three weeks before we knew we’d marry. What’s more, I had never thought I’d marry out of my religion. But I was drawn to Ken’s sense of humor, his love of learning, his concern for people living in poverty.

Ken recalls being surprised that my parents opposed our marriage plans. He had thought only Mormons were unhappy when their children married out of their religion. My parents were so desperately unhappy that they secretly and uncharacteristically hired a private detective in the hope of discovering something unsavory about Ken or his family. They discovered nothing negative, of course, but that still didn’t mean that we received my parents’ blessing—quite the opposite.

Orthodox Jews traditionally go into mourning when a child marries a non-Jew, just as if he or she had died. My parents, who ate only Kosher food but attended synagogue in their small New Jersey town only on major holidays, considered doing this but decided not to. While I had always had a warm and loving relationship with my father, he could not bring himself to speak to me for two years. My mother, more practical perhaps, attended our marriage ceremony in a judge’s chambers; but we asked her not to attend the party we threw for ourselves, since she was obviously not in a celebrating frame of mind. From my side of the family, only one aunt and uncle, who themselves had a mixed marriage, came to our wedding. We received no gifts from my formerly close-knit family, though my twenty-one-year-old brother was secretly supportive. Fortunately I can report that later my parents grew to love and appreciate Ken and his family; in fact, his mother and mine visited Israel together. My most religiously practicing aunt and uncle enjoy a very close relationship with Ken.

In contrast to the tension from my family, Ken’s divorced Mom and I met several months before the marriage and immediately liked each other. A very devout Latter-day Saint, she understood that Ken loved me, and she was never other than supportive of our marriage. I assume that she has hoped I’d convert, but, wisely, she has never actively tried to influence me to do so.

After our honeymoon, she hosted a reception which was my intro duction to practicing Latter-day Saints. Used to lavish Jewish receptions that inevitably featured copious amounts of food at a sit-down dinner, I was surprised by large numbers of guests—so many people and so little food! I was very touched, however, when a man in his late seventies, a former bishop, told me, “You’re marrying for the best reason . . . love.”

After nine months in Salt Lake, we moved back to New York City for Ken to earn his master of social work degree. We cannot recall anyone there discussing religion. Utah had been different, however. People asked me if I were “a member.” I remember sarcastically and in culture shock telling Ken that I wanted to reply, “No, I’m not a joiner.” This awkward phrase has not been put to me in years, thank goodness. Accustomed to New York City’s diverse ethnic culture, I was also caught off guard by the fair-skinned, fair-haired homogeneous appearance of the Latter-day Saints. In a crowd, I was obviously different. I remember hearing an elderly neighbor whisper loudly to her husband as I walked by, “Isn’t that the Jewish girl?”

Ken and I returned to Salt Lake City after he earned his master’s degree, and he began working as the director of a social services program. Participation in religious services was and has not been a priority for either of us. I now attend synagogue services only when specific programs interest me or when friends’ children are being Bar or Bat Mitvahed (ceremonies for thirteen- year-olds). I also attend Holocaust memorial services and Israel independence celebrations. Other than funerals, Ken has attended only two LDS services since we met—the farewell and homecoming meetings for his mother’s mission to London. Furthermore, I have not attempted to indoctrinate our children in the teachings of Judaism. Ken and I agreed from the start that our children would be reared with the best moral and ethical code we could provide, but in no formal religion. Our teenage sons have friends who practice their various religions in varying degrees. The boys have not, though, been drawn to any religion whose services they have attended.

While I may not be an observant Jew, I do enthusiastically identify myself as Jewish. I value Judaism’s traditions and culture and honor those in my family who have been practicing members. I’m very proud of my heritage, as Ken is of his. However, while I lived in New York City and when we first moved to Salt Lake, I didn’t seek out any Jewish organizations or support. But I did always contribute financially to Israel. Maybe I should digress and observe that Ken supports, or at least never minds, my check-writing to charitable causes. Whether or not they are Jewish charitable organizations is beside the point for him. He simply endorses ways to fight poverty or support the arts that go beyond LDS tithing contributions. For my part, I think the LDS practice of tithing is wonderful, and I observe that the contribution and volunteer ethic is especially strong in both of our cultures. As I have knocked on doors and volunteered many hours, so has my dear mother-in-law and so did my very Jewish mother until her death. If volunteerism hadn’t been so much a part of Ken’s church upbringing, he might not have been so tolerant of the many hours I have given to many causes, especially to the National Council of Jewish Women here in Salt Lake City.

I must note, however, that when I have solicited for the Cancer Society and the Heart Association, I have gathered that some Latter day Saints think that because they tithe, they don’t need to contribute to other causes. Perhaps their resources are stretched, but I cannot help but wish that they would consider themselves part of a larger whole, not just the LDS community.

Unfortunately, I have not always felt this type of connectedness with those of other faiths. I grew up in a predominantly Catholic community. Because education was not a priority in my New Jersey hometown, my parents sent me to a small Hebrew-English school through eighth grade. I received a wonderful education, but I was embarrassed to be seen leaving for school when the neighborhood kids were enjoying their Christmas and Easter vacations. Towns people who didn’t know my dad was Jewish would often make anti-Semitic statements in his presence. He’d never confront these insensitive people, but he would come home and tell his family. Perhaps because I’m accustomed to being part of the minority, I can accept certain political decisions made by the LDS majority in Utah. However, I am offended when public prayers are made “in the name of Jesus Christ.” Ken understands this and has made me feel a little less offended by explaining that to Mormons, it’s not a prayer if it’s not said this way. I have shared this explanation with Jewish and Catholic friends who have also bristled at such prayers in public.

Ken and I were the first in our families to receive college degrees, and our parents were especially proud of our educational achievements. To an extent, our cultures share a love of words, books, and knowledge. There is a difference even here, though. When I asked a friend, Jewish by descent only, what he thought made our shared culture unique, he replied after some thought: “We have more books per capita in our homes. The only other comparable group is the Boston Brahmins, and they have more money and have been educated for more generations.” The Sunstone Mormons I know love books too, but in some segments of the LDS populace I sense a reluctance to study and probe, an attitude totally foreign to my culture. I am also dis tressed by a persistent, vocal, ultra-conservative element in the Mormon population.

I see connections between our cultures in regard to family emphasis too, but even here there are shades of difference. We all say we love children. Jewish people feel they are demonstrating this when they choose to have two or three children to whom they can give all the enrichment they can afford and spend as much time as possible nurturing. By contrast, I sometimes sense that in the Mormon culture the emphasis is on quantity. On this point, Ken sides with me and my culture. We waited six years and had a home and nest egg before our first child was born.

On related themes, both of us feel that people with many children in public schools should pay more in taxes toward their children’s education, but Ken is less comfortable than I am with pro-choice stands. His discomfort, I maintain, can be directly traced to his religious back ground.

Conservative people in Utah see me as a “spunky woman”—the opposite of passive. Perhaps I would have had the same spunk had I been raised a Latter-day Saint. Ken’s paternal grandmother, reared in the home of a Manti, Utah, patriarch, I’m told, was unconventional enough to succeed in door-to-door sales in the thirties at the same time pursuing her love of opera singing and rearing five children. My maternal grandmother and mother were not passive either. I have taught my own brand of assertiveness to a number of LDS friends—as the Jewish ones haven’t shown a need. My Mormon subjects have been eager students. I have helped them handle problems with everyone from school administrators to plumbers, husbands to divorce lawyers.

As for Ken, his reaction to my refusal to passively accept what I feel to be unjust ranges from cheers of support to mild amusement to downright horror. During the height of debates about the E.R.A., he received a letter from Church authorities lamenting the lack of involvement of some Mormon wives in Relief Society and instructing him to tell me to get involved! It isn’t the nature of our relationship to tell each other what to do, and, to be honest, I had to read the letter twice. It was so foreign to my culture, I couldn’t believe what I had read. On the other hand, if I were an Ultra-Orthodox Jew, this sort of dictum would be expected.

I am here to share my perspective with you, and my Jewish friends see me as one who knows more about LDS religion and culture than they do. Am I right in counseling my Jewish friends to be honest with Mormon missionaries and other proselytizing people instead of simply being gracious but feeling inwardly resentful? I confess I was taken aback when four members of the bishopric arrived unannounced one evening as Ken and I were unpacking in our new home. It was without malice that I said, “I hope you didn’t come to talk about religion.” The bishop didn’t miss a beat and replied, “No, we just want to meet our new neighbors”; Ken and I and the four men had an enjoyable chat. Latter-day Saints should be aware that the Jewish religion not only doesn’t encourage proselytizing, it makes it difficult for people who seek to convert. Perhaps this explains my extreme reaction when the bishopric came to call. A visit with missionary motive was alien, if not antithetical, to my background.

While the Word of Wisdom was not something I was aware of before I met Ken, it was not an issue on which we differed at heart. Moderation in all things. Wine is used in the practice of the Jewish religion, but Jewish people have traditionally had a low alcoholism rate, although this is changing among the less practicing. My parents would always offer guests one drink. I never saw anyone drunk, and I drink very little. On the other hand, until he moved to New York City, Ken had never been at a party with alcohol where he didn’t witness drunken behavior. His active LDS friends would ask him why he wasn’t wild, since he didn’t have the constraints of his religion. His answer was that he isn’t basically a wild person. I am happy that smoking is anathema in his culture. I stopped smoking my one cigarette a day when we began dating. I’ve never been sorry.

For all of our cultural and religious differences, Ken and I have as much or more that we share. Both enrich our marriage and our lives. We still share what brought us together: the arts, travel, political discussions, our many and varied friends, and of course parenthood.

When Karen Moloney, who organized this panel, asked the only rabbi in Utah to come up with a synagogue-attending Jewish person married to a practicing Latter-day Saint, he drew a total blank. Hence you’re hearing from me. When I asked a close friend who is president of the synagogue’s women’s group if she thought I was qualified to offer this presentation, she replied, “Wilma, you’re the most Jewish person I know.”

You figure it.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue