Articles/Essays – Volume 10, No. 3

Illustrated Periodical Images of Mormons, 1850-1860

Image history—how the Mormons were viewed by others—has been a fruitful approach used by several historians during the past decade. Studies of press coverage of Mormonism have been produced by Richard Cowan, Brigham Young University; Dennis Lythgoe, University of Massachusetts; and Jan B. Shipps, Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis. Leonard J. Arrington, Church Historian, and Jon Haupt have studied the treatment of the Mormons in nineteenth century novels, and Richard Cracroft, Brigham Young University has looked at the same subject from the point of view of humorists. Now Gary L. Bunker and Davis Bitton, professors of psychology and of history at Brigham Young University and the University of Utah respectively, are examining visual images of the Mormons in an effort to understand the emotional overtones of the anti-Mormon crusade of the nineteenth century. The present article is the continuation of a project first presented at Brigham Young University in November 1975.[1]

In a speech in the tabernacle on June 19, 1853, Brigham Young observed:

(some) thought that all the cats and kittens were let out of the bag when brother Pratt went back last fall, and published the revelation concerning the plurality of wives: it was thought there was no other cat to let out. But allow me to tell you . . . you may expect an eternity of cats, that have not yet escaped from the bag. Bless your souls, there is no end to them, for if there is not one thing, there will always be another.[2]

During the 1850’s, these cats and kittens were used by the media to create a public image of Mormonism that would endure into the twentieth century.

Although the two preceding decades contributed to the negative reputation of Mormonism, the impact was more regional than national; there was not a true popular consensus concerning the alleged threat of Mormonism.[3] The martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith and the subsequent involuntary exodus to the West even aroused some national sympathy.[4] Then came the 1850’s—and by theclose of the decade media depictions of the Mormons, both textual and pictorial representation, had firmly established the national stereotypes of Mormonism. There would be later embellishments and elaborations as new events transpired, writers wrote, and artists plied their craft, but these would be variations on themes laid down during or before the ante-bellum period.

Three important developments combined to fix the negative stereotype of Mormonism. First, the social climate in the United States permitted, even encouraged with impunity, open hostility to unpopular ethnic, racial and religious groups. As historian David Brion Davis showed several years ago, the antipathy toward Mormons and other similarly perceived groups, owed more to the paranoia of the American population than to any genuine threat.[5] Second, several incidents in Mormon country in the 1850’s stimulated resentment: the public avowal of polygamy in 1852; clashes between Mormon leaders and U.S. officials that led to the “runaway judges” in 1853 and their charge that Utah was a dictatorial theocracy; the Utah War of 1857-58 that reiterated these same charges of a polygamous, autocratic, treasonous Mormonism and raised the question to a higher level of national consciousness; and, finally, the Mountain Meadows Massacre, which, when evidence was uncovered and publicized, confirmed all the worst suspicions. From the point of view of anti-Mormons, a better stereotype of Mormonism could not have been provided had it been specifically staged for that purpose.

The third development in the establishment of the Mormon stereotype was the emergence and proliferation of the illustrated periodical. “The illustration mania is upon our people,” observed the Cosmopolitan Art Journal in 1857. “Nothing but illustrated works are profitable to publishers; while the illustrated magazines and newspapers are vastly popular.”[6] The Lantern, Yankee Notions, Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly Newspaper (later Leslie’s Weekly), Harper’s Weekly, Vanity Fair and The Old Soldier all began publication during the 1850s, and all displayed Mor monism both textually and pictorially.[7] There had been other important vehicles of expression before—books, pamphlets, broad sides, almanacs, separately published prints—but none of these had as much power to shape attitudes among large numbers of people as did the illustrated periodical. At the outset of the Civil War both Harper’s and Leslie’s weeklies exceeded the 100,000 circulation mark, and the monthly Yankee Notions sold 150,000 copies as early as 1858.[8] Words and pictures worked together then to produce the unkind stereotype.

In 1851, federally appointed judges Brocchus and Brandebury left Utah and returned to Washington with charges that the Mormons were disloyal to the United States, that they were practicing polygamy, and that Brigham Young had been guilty of malfeasance as governor. Pro and con discussions of these charges included a highly critical editorial in the St. Louis Republican accusing the officers of abandoning their posts.[9] The Lantern, an illustrated weekly, offered a satirical account, as follows:

Judges are not recognized in the Scriptures of Utah—especially United States Judges, two of whom have been compelled to make their exodus to the Atlantic Slope. Their feet were beautiful upon the mountains, for they journeyed briskly. And the twain have writ a chronicle, and the chronicle is true. Their record saith there is no division in the Mormon Church, but rather multiplication. The High Priest, even Brigham, hath forty wives spiritual, and all the forty are under twenty-five. . . . And there be other Saints, whose matrimonial crops are plentious and heavy in the cradle of the husbandman; for Utah is not a barren land. . . . Now the Prophet Young, whose given name is Brigham, denieth the authority of this Nation, and goeth for the “solidarity” of the Mormon peoples and opposeth intervention. And lest the righteous be tempted with the public silver and gold, he seizeth and putteth it away privily, where no man can find it. And the Saints are satisfied with the Prophet and mourn not the loss. All these things, and more also, are writ in the Chronicles of the Judges, who tarried awhile in the land.[10]

This incident illustrates that very early polygamy and hostility to the United States were linked together in portrayals of the Mormons.

A fascinating lithograph published in the April 1852 issue of The Old Soldier employed double entendre to exploit the twin themes of polygamy and Mormon defiance (see illustration l [Editor’s Note: For all illustrations, see PDF below]).[11] A brief textual commentary supplemented the caption:

Nothing short of disgrace, disaster, and defeat can await the United States troops, should they be reckless enough to attack the Mormons of Deseret in their formidable entrenchments. Protected by such “Breastworks” they may safely banish fear, while with their Light Artillery they can raise such a noise about the ears of their enemies that neither tactics or discipline for a moment can withstand. Total annihilation must inevitably result.

The simple reversal of sexual role expectation subtly maligned both Mormon men and women. The most remarkable thing about this lithograph is the way it anticipated the Utah War and provided a humorous situation that would be exploited later on.

Most of the illustrations published between 1852 and 1856 focused on polygamy. Some of them were relatively innocuous. For example, Thomas Butler Gunn, a cartoonist for The Lantern, had Brigham Young exclaim to Horace Greeley, “Say, Brother Greeley, Have you got the Mormon Life of Scott fixed yet? If yer Have, I guess I’ll take a thousand, as I should like to give a copy to each of my wives!” (see illustration 2).[12] While the exaggeration of the number of wives produced the primary humor, the language conveying the image of a backward Brigham added another ludicrous element. In 1854 Yankee Notions’ first cartoon on Mormonism depicted the “fashionable arrival” of “Mr. Pratt, M.C. from Utah, twenty wives and seventy-five children.”[13]

Two years later the same periodical began the use of animal symbolism to capture the essence of Mormonism. A sketch of a rooster surrounded by hens was captioned “A foul (fowl) piece of Mormonism.”[14] Polygamy could be thus portrayed, or hinted at, while at the same time establishing an image of the Mormons as somehow less than human.[15]

When misunderstandings between the Mormons and the federal government led to the sending of an army under General Albert Sidney Johnston to the Utah territory, Brigham Young insisted on his rights as governor and prepared to resist an unprovoked and unlawful invasion. The result was the short-lived Utah War, consisting mainly of harassment of the advancing federal troops by Mormon guerillas, a delay of the army, a threat of Mormon evacuation of their Utah settlements (partially carried out by the Big Move) and eventual settlement and reconciliation.[16] During much of 1857 and 1858, this campaign provided subject matter for the national periodicals.

The Buchanan administration did not escape ridicule for this needless expenditure of energy and funds. But for the Mormons, the War simply provided a new occasion to bring them repeatedly onto the public stage as objects of ridicule—as polygamists and traitors. A Philadelphia lithographer seized the opportunity to make some quick money, and offered for sale an illustration of fine detail and flagged captions that was essentially a restatement of of the early “Breastworks” idea (illustration 3).[17] The theme had received an added boost from Mormon leader Heber C. Kimball’s 1857 tongue-in-cheek remark: “I have wives enough to whip out the United States.”[18]

By this time two of the new illustrated weeklies—Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly and Harper’s Weekly —had surpassed their journalistic rivals. More than any of the others, they established the illustrated weekly as a permanent fixture of American media. And, significantly, both of these periodicals showed unusual interest in the Mormons and the Utah War.

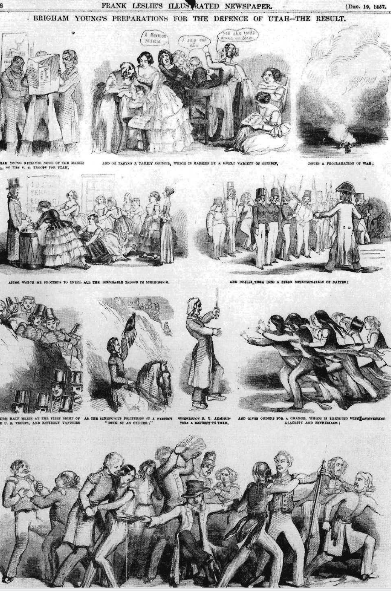

The first “Mormon” cartoon appeared in Leslie’s on December 19, 1857 (illustration 4). It was a serial cartoon which anticipated the comic strip of a later period, and containing the popular theme of a female Mormon militia, but with a new twist: the fickle female troops lose combat readiness the minute the dashing gentile appears! With Mormon men unable to match the allurements of their gentile counterparts, the Utah War comes to an end.

Six months after the appearance of the serial cartoon, an artist for Leslie’s, Justin H. Howard, sketched another imagined resolution of the war (illustration 5). Soldiers from Johnston’s army were hiding under the huge hoop skirts of the Mormon women, who, according to the caption, made “An Amicable Settlement Of All Their Difficulties.”[19] Another cartoon by Howard on the same page parodied Brigham Young, complete with balloon caption, fleeing “from the wrath to come.” It was the image of a cowardly leader apparently leaving his wives and children to fend for themselves (illustration 6).

Harper’s Weekly, the other highly successful illustrated weekly, was offering its own satirical version of the U.S. invasion of Mormon Utah. The first Mormon cartoon published in Harper’s Weekly appropriated the familiar theme of Mormon women, who, according to the caption, made “An Amicable Settlement Of All Their Difficulties.”[20] Another cartoon by Howard on the same page image was not enhanced by his caricaturization as the dull, piggish caretaker of Brigadier General Bombshell’s bevy of wives (see illustration 8). [21] And like Leslie’s, Harper’s gave its satiric version of the consummation of the war (see illustration 9)[22] The shackled Mormon men were obliged to watch as their consorts catered to their beguiling captors. There was a mixture of condescen sion and self-congratulation inherent in the theme of the “dashing gentile.” Such cartoons ridiculed their subject, but they also entertained, and humor may have provided a pretext for the acquittal of conscience.

Of all of the illustrated weeklies of the 1850’s, none could compare with Harper’s Weekly in the space allocation given to the Mormons. Nearly every week during 1857- 58 there was either an article, brief news item or illustration. The negative editorial stance towards the Mormons was never in doubt, as the following sampling of news dispatches and articles suggests:

February 21, 1857. In regard to the Mormon children, they appear like a neglected uncared-for set, generally dirty and ill clad. The majority of them are girls, and this troubles the women very much, for they know a female is doomed to slavery and a life of misery . . . These children are suffered to grow up in ignorance and vice. Without the hallowed influence of home to restrain them, they are vicious, profane and obscene.

May 23, 1857. The Bishop of Provo, a creature named Carter, officiated at the funeral of Nash, and after concluding the prayer over the dead body of the father, turned to the weeping girl, informed her that she was now unprotected, and must become his wife! In less than ten days she was forced to yield, and now swells the number of Carter’s “spirituals” to seven.

October 31, 1857. A great number of missionaries are engaged in the fields of China, and especially in the manufacture of tea, into which, during their labors, they incorporate an insidious but fatal poison . . . These poisons are various kinds. Some are so slow that long periods elapse before they take effect . . . One poison within the knowledge of Brigham possesses qualities that remain inert in the human system for year before its fatal consequences are developed.

November 28, 1857. But why should not someone suggest to these perserving Saints that South America contains thousands of square leagues of unoccupied territory, blessed with a glorious climate and a fertile soil, where no government would molest, no soldiers attack them, and where they might work out their problem in safety for at least a century to come?

With few exceptions the illustrations in Harper’s Weekly were more benign than these discordant verbal accounts. On October 10, 1857, three illustrations showed Brigham Young’s family going to church, in their family parlor, and at a family dinner. A family dinner. A fourth panel was a view of a Mormon dance with a high ratio of females to males. But the title, “Scenes in an American Harem,” was sufficiently titillating to make up for any lack of excitement in the pictures themselves. Most of the additional thirteen pictorial representations were engravings taken from the photographs of David H. Burr, the Surveyor-General of Utah Territory and the Deputy Surveyor, a Mr. Mogo.[23] There was nothing sensational about the photographs, mostly selected scenes in Salt Lake City, but the accompanying text managed to convey invidious connotations. For example, “The Calaboose in Salt Lake City” was described as the place where gentiles were incarcerated whose “crime was that of being American citizens.”[24] The residence of Heber C. Kimball, “the most vulgar and profane man in the Mormon church,” was matter of factly shown with a damning commentary: “His ‘spirituals’ frequently run away from him, and when at home quarrel so much that he finds several separate buildings absolutely necessary. Our view of his group of dwellings is the best evidence of the fact.”[25] Thus the negative message could be carried by the picture, by the accompanying text, or by both.

When Yankee Notions printed “Ye Popular Idea of Brigham Young and his Followers” in April, 1858, it effectively distilled the contemporary view of the Mormons (illustration 10).[26] At the same time the illustration demonstrated the power of pictorial shorthand to convey a number of ideas. The goat caricature of Brigham Young was a symbol of lust. The horns of some of the prostrate followers was not a new idea, but was an early graphic representation of that image.[27] The enthusiasm of the females in the background, apparently for Brigham Young, was one of many stereotypes of Mormon women, some of which went directly contrary to this view. The wild-eyed facial expressions on the adherents to this singular faith underscored their peculiarities. And the flag of liberty in the midst of the Mormons was a parody of the “indiscriminate allegiance” of the submissive followers.

A companion cartoon in the same issue of Yankee Notions presented another persistent theme (illustration 11). The ultimate origin of a cooperative alliance and common destiny of Mormons and Indians was theologically grounded in the Book of Mormon. Suspicion of actual Mormon complicity with Indians originated in the 1830’s, but the possibility of alliance had been renewed with the Utah War.[28] “God Almighty will arouse every tribe and every nation that exists in the East, West, North, and South,” said Heber C. Kimball, “and they will be on hand for our relief.”[29] When the bellows of exaggeration and distortion blew the sparks of substance, an enduring image was forged from the fire. The grotesque caricature of the Indians symbolized the contempt in which they were held, and linking the two unpopular groups in the public mind did not prove a boon for the public relations of either the Indian or the Mormon.

The crowning blow to any Mormon hopes that their national reputation would turn favorable or dissipate with time was the Mountain Meadows Massacre of 1857, in which members of a wagon train from Arkansas were killed. This unfortunate event was investigated as early as 1858. The present scholarly conclusion is that local Mormon leaders in Southern Utah were mainly responsible for the massacre, and that Brigham Young did not know about the action until it was too late to stop it.[30] During the closing four decades of the nineteenth century, however, there was a lingering suspicion among non-Mormons that Brigham Young had been personally responsible. The mere fact that the incident occurred in the midst of the Mormons in sparsely settled Utah was enough to create a powerful negative symbol. On August 13,1859, Harper’s Weekly published a front-page expose of the massacre with accompanying sketch. Already thought of as strange and exotic because of plural marriage, the Mormons were also seen as stupid, dishonest pawns of a cruel, tyrannical prophet—motifs nicely combined in the Mountain Meadows Massacre, which, incidentally, appealed to the perennial human interest in murder and violence. During the post-Civil War generation, few if any subjects would be repeated more often in the visual portrayal of Mormonism.

Were not the Mormons partially responsible, then, for the shaping of their own dubious public image? Since treatments of media coverage understandably differentiate between the image and the reality, it is easy to assume that the public reputation of any group as conveyed in words and pictures is largely trumped up. Yet the essence of caricature, indeed its whole effectiveness, lies in the kernel of truth selected by the artist or writer and then magnified in grotesque proportions. The Mormons did in fact practice polygamy; they did express misgivings about the United States, and they did participate in the Utah War; a massacre did take place, and so on. We maintain, however, that selecting certain points, magnifying them, and taking them out of context for purposes of ridicule created a severely distorted view of the Mormons. Balanced discussions were never included in the satirical articles or cartoons—but of course they could not be if the satire was to have its intended effect. So the Mor mons were in part responsible for the unfavorable stereotype of themselves that became standard, but this does not mean that the stereotype was ultimately fair or accurate. Stereotypes never are. Blacks, Jews, Poles, Germans, Japanese, Chinese—any study of other group stereotypes demonstrates the same point.[31] Our analysis of the image of the Mormons is thus a case study of a larger phenomenon.

An illustration in the February 11, 1860 Vanity Fair summarized the legacy of the 1850s for the image of Mormonism (illustration 12).[32] A sub-human, horned Brigham Young gestured with one hand at a sign warning gentiles, with the other hand firmly secured to his “Pandean, polygam pipe.” The illustrator’s idea derived from a news account detailing Young’s recent illness: “When he is seen he has his head muffled up in a handkerchief.” Imagination then took over. The text filled in the details.

The Mormon Hierarch has long been playing a game of “blind man’s bluff” with the government of this country—a game in which we are sorry to think the government has allowed itself to be so utterly cornered that the muffler should, long since, have been conferred to Presidential features. But matters are now so bad at Polygamutah, that even Brig. Young himself declines, perhaps, to give his countenance openly to them, and, therefore, keeps the blinder on so as to be blind to what is going on about him. . . .

It is high time for that Pan to be “brought over the coals.” Territories are less savage when abandoned to their primitive bears and indigenous buffaloes, than when subjected to the half-civilized influence of such a socialism as the Mormon megatherium: and we doubt if the Valley of the Lake of Salt, in the days when no footmarks fell on its crystal-frosted soil save those of the fierce beast of the mountain and plain, ever displayed, have so beastly a sight as that of the grizzly goat-herd, Brigham, leading his hoofed and homed flock to the sound of his Pandean, Polygam pipe.”[33]

With the coming of the Civil War, slavery, the other “twin relic,” diverted the attention of the nation and the media away from Mormonism.[34] Rarely does war give people of a participant nation respite from the rigors of life, but the isolated Mormons now had time to patch wounds from what had been a one-sided war of words and pictures. It was only a matter of time, however, before the verbal and pictorial war against the Mormons resumed with fresh ammunition, more sophisticated weaponry and a new cadre of soldiers.

Picture Credits

1. Mormon Breastworks and U.S. Troops—Courtesy The American Antiquarian Society 2. Scene at the Tribune Office—The Library of Congress

3. Brigham Young From Behind His Breastworks Charging the United States Troops—Courtesy The American Antiquarian Society

4. Brigham Young’s Preparations for the Defense of Utah—The Result—The Library of Congress 5. The Mormon Ladies Make an Amicable Settlement of All Their Difficulties—The Library of Congress

6. Flight of Brigham Young, From a Drawing Done Here On The Spot, By Our Own Clairvoyant Artist—The Library of Congress

7. Brigham Young Mustering His Forces To Fight The United States—Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

8. Affairs At Salt Lake City—Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

9. Frightful Scene of Carnage and Desolation at the Sack of Salt Lake City By The United States Troops—Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

10. Ye Popular Idea of Brigham Young and his Followers—The Library of Congress

11. Defiant Attitude of Brigham Young and Ye Indians Towards Ye Uncle Sam—The Library of Congress

12. The Veiled Prophet of Polygam Utah—The Library of Congress

[1] [Editor’s Note: There is no footnote 1 in the body text of the PDF] This article is part of a larger project by the authors dealing with pictorial images of Mor monism between 1830 and 1914.

We would like to acknowledge the able assistance of Georgia Bumgardner, curator of Graphic Arts at the American Antiquarian Society.

[2] Brigham Young in Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latterday Saints’ Book Depot, 1855- 86), 1:188.

[3] Examples of early works portraying the Mormons in negative colors are Eber D. Howe, Mormonism Unvailed (Painesville, Ohio, 1834); John C. Bennett, The History of the Saints (Boston, Mass.: Leland and Whiting, 1842); Henry Caswall, The City of the Mormons (London, England: G.G.F. and J. Rivington, 1843); and Origen Bacheler, Mormonism Exposed (New York, 1838).

[4] See Davis Britton, “American Philanthropy and Mormon Refugees, 1846-1849” (unpublished); and the brief “Tea and Sympathy,” in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 3 (Spring, 1968): 142-144.

[5] David Brion Davis, “Some Themes of Counter-Subversion: An Analysis of Anti-Masonic, Anti Catholic, and Anti-Mormon Literature,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 47 (September i960); 205-24; and John Higham, Strangers In The Land (New York: Atheneum, 1975), preface to second edition. We are aware that prejudice is multicausally determined. Space does not permit us to discuss the complex determinants, but the brief statement in the text is intended to refer to that complexity.

[6] Frank L. Mott, A History of American Magazines: 1850-1865, 5 vols. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1957), 2:192.

[7] “Yankee Doodle and John Donkey eked out brief careers at the end of the forties, the Lantern threw its glimmer over Millard Fillmore’s last two years in the White House, and Yankee Notions held out from 1852 into the seventies. But the first magazine to establish itself firmly in political caricature was Harper’s Weekly, founded in 1857. Then, in the fateful month of John Brown’s raid, December 1859, Vanity Fair appeared: … ” Allan Nevins and Frank Weitenkampf, A Century of Political Cartoons (New York: Scribners, 1944), p. 13. Novels published during the same period have been studied by Leonard J. Arrington and Jon Haupt, “The Missouri and Illinois Mormons in Ante Bellum Fiction,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 5 (Spring 1970): 37-50.

[8] Frank L. Mott, A History of American Magazines: 1850-1865, 5 vols. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1957) 2:10, 182. The Old Soldier, The Lantern and Vanity Fair were less successful, lasting six months, eighteen months and three years respectively.

[9] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols. (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1957), 3:535-37.

[10] The Lantern, 17 January 1852.

[11] Old Soldier, 1 (i April 1852). A note in the file at the American Antiquarian Society by the late director of the Society, Clarence S. Brigham, suggests: “This set of lithographs in the Old Soldier was published in 1852 at 69 Nasaau Street, New York. John L. Magee was listed as a lithographer at 69 Nasaau Street, in New York Business Directory for 1852-53. He executed similar lithographs. It has been thought that these lithographs were by David C. Johnston, but in no way are they like his work, and he was in Boston in 1852.”

[12] The Lantern, 18 September 1852, The caption alluded to the common practice of the day for newspapers to print inexpensive books written by Sir Walter Scott and others. See Russell Nye, The Unembarrassed Muse (New York: Dial Press, 1970), 25.

[13] Yankee Notions, July 1854.

[14] Yankee Notions, May 1856.

[15] On animal symbolism, see more generally Leonard J. Arrington and Davis Bitton in topical history of the Church (forthcoming).

[16] On the Utah War see James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1976), ch. 9, and supporting bibliography.

[17] The lithograph is in the graphic arts collection at the American Antiquarian Society. The curator of graphic arts there did not know the source of the print except that it was “for sale at 217 Walnut Street Philadelphia.” It may have been a separately published print. The estimated date given to the lithograph is 1857.

[18] Heber C. Kimball in Journal of Discourses, 5:95, 250, sermon delivered 26 July 1857 and 20 September 1857.

[19] Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 5 June 1858.

[20] [Editor’s Note: In the PDF body text, this is labeled as a second footnote 19] Harper’s Weekly, 28 November 1857.

[21] [Editor’s Note: I could not find a footnote 21 in the text, so I placed it here] Harper’s Weekly, 1 May 1858.

[22] Harper’s Weekly, 22 May 1858.

[23] The experience of Burr and Mogo in Utah may have contributed mor e to the image of Mor monism than their rather mundane photographs. They reported being harassed severely by Mor mons. See Harper’s Weekly, 1(31 October 1857), 694. For more detailed descriptions of relations between the two surveyors and the Mormons see: Gustive O. Larson, The Americanization Of Utah For Statehood: (San Marino, California: The Huntington Library, 197a) p. 14 and Nels Anderson, Desert Saints (Chicago, 111.: University of Chicago Press, 1966), pp. 149-52.

[24] Harper’s Weekly, 6 November 1858.

[25] Harper’s Weekly, 18 September 1858.

[26] Yankee Notions, April 1858.

[27] Cf. Karl E. Young, “Why Mormons Were Said to Wear Horns, ” in Thomas E. Cheney, ed., Lore of Faith and Folly (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1971), pp. 111-12. As early as 1842 General Wilson Law, in a conversation with Joseph Smith, had said, “Well, from reports, we had reason to think the Mormons were a peculiar people, different from other people, having horns or something of the kind; but I find they look like other people: indeed, I think Mr. Smith a very good-looking man. ” Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Saints, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., i960), 5:214.

[28] See for background Lawrence G. Coates, “A History of Indian Education by the Mormons, 1830-1900” (Ph.D. dissertation, Ball State University, 1969).

[29] Journal of Discourses, 5:278.

[30] On the massacre the standard treatment is now Juanita Brooks, The Mountain Meadows Massacre (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950).

[31] Gordon W. Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (Garden City, New York: Doubleday Co., 1954).

[32] Vanity Fair, 11 February 1860. According to Frank Weitenkampf, H. L. Stephens did the car toons for Vanity Fair. Frank Weitenkampf, American Graphic Art (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1942), 229.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Between 1861 and 1865 there was a grand total of six relatively brief references to the Mormons in Harper’s Weekly, a far cry from the example of years 1857-1860. To be sure, the Mormons were not forgotten during the Civil War, but there were far more pressing priorities.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue