Articles/Essays – Volume 05, No. 1

The Mormons in Early Illinois: An Introduction

The Illinois period of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints commenced eight years after the founding of the Church in Fayette, New York on April 6, 1830, by Joseph Smith. From New York the Church spread westward into northern Ohio and western Missouri. During the early 1830’s, the headquarters of the Church was in Kirtland, Ohio. Due to internal difficulties, apostasy, and persecution, members of the Church in this area eventually joined the other main center of the Church in Missouri.

Mormons had been in Missouri as early as 1831, where they centered around Independence in Jackson County. As in Ohio, they had difficulty with their neighbors and were driven from Jackson County in November, 1833, to settle across the Missouri River in Clay County. Under pressure they left Clay County in the summer of 1836 for the uninhabited north half of Clay County, which was soon organized into the “Mormon County” of Caldwell. There Church headquarters were established at a place called Far West.

The area around Far West built up quickly. To this new center of Church activities came the Ohio Mormons (in 1838), as well as many from Canada and the eastern United States who had joined the Church through missionary activity. This sudden influx created new conflicts, and mobs, motivated primarily by political, economic, and religious reasons, again plundered the Mormons, who prepared for defense; a near state of civil war existed. On October 27, 1838, the Governor of Missouri, Lilburn Boggs, signed the “Ex termination Order” which read in part, “. . . the Mormons must be treated as enemies and must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public peace. . . .” Church leaders were imprisoned and the rest of the Church membership had the choice of denying their faith and making peace with the mobs, or of fleeing the state. Thousands sought asylum in the state of Illinois and in Iowa Territory. Many spent the winter of 1838-39, and the spring of 1839, in and around Quincy, Illinois, whose citizens were sympathetic toward the destitute Mormons.

Finally on April 16, 1839, Joseph Smith and other leaders of the Church were allowed to escape from their prison in Liberty, Missouri, and joined the members of the Church at Quincy. Shortly after his arrival there, Joseph Smith purchased land at Commerce, Illinois. The first purchase was made May 1, and on May 10, Joseph Smith and others took up residence in Com merce.

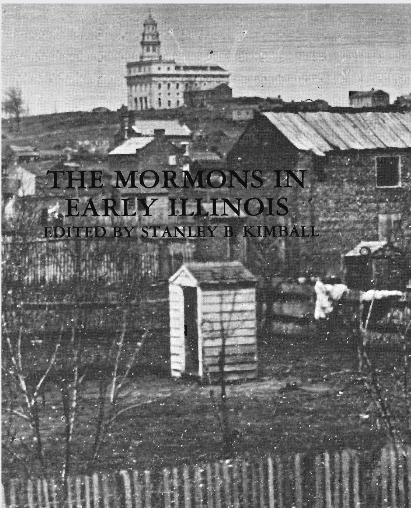

Throughout the summer of 1839, members of the Church came into the Commerce region. They cleared the land, drained the swamps, and built houses. In September streets and lots were laid out in a new area adjacent to Commerce. It was called Nauvoo, a name which Joseph Smith said was from Hebrew, meaning “beautiful place of rest.” By the end of 1840, the city had a post office and had been granted a city charter by the state of Illinois.

The Charter made Nauvoo virtually a “city-state” with its own militia, the Nauvoo Legion, which became an army of about 3,000. Joseph Smith was determined to provide protection against a repetition of past persecutions.

Nauvoo grew fast as members and new converts from the East, Canada, and the British Isles flooded into the city. No accurate census was ever taken, but by the summer of 1841, Nauvoo had 8,000 to 9,000 inhabitants. Between 1844 and 1846, with more than 12,000 residents, Nauvoo was the largest city in Illinois.

For a variety of reasons—mainly religious and political differences, the enmity of apostates, and the envy of surrounding communities—persecution began again. Work on the Temple and other enterprises was slowed down by mob harassment. The situation worsened and was climaxed by the murder of Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum in June, 1844, while they were in protective custody in the Carthage jail awaiting a hearing on charges of treason.

Following this act the Nauvoo Charter was repealed, and mob activity, only partially checked by the state militia, grew in intensity. During the fall of 1845, an agreement was made between the Church and a commission from the State of Illinois that the Mormons would leave the following spring. But the mistreatment of the Mormons continued and the first members of the Church under the leadership of Brigham Young left Nauvoo in February, 1846. By September of that year the last members of the Church had left Nauvoo and joined the exodus to the West, eventually re-settling in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake. Their Temple stood as a symbol of their faith until November, 1848, when it was burned by those who feared it might attract Mormons to the area again.

In 1961 the Lovejoy Library of Southern Illinois University at Edwards ville began collecting materials pertaining to the early history of the Mor mons in Illinois. The major purpose in this effort was to do what had never been done before—to bring together copies of as many primary sources regarding the early history of the Mormons in Illinois as possible to better enable qualified scholars and students to understand this important phase of Mormon, Illinois, and American history.

The collection consists of about 84,000 pages of material, much of which is on microfilm. My Sources of Mormon History in Illinois, 1839-48: An Annotated Catalogue of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University was printed by Southern Illinois University in 1964 and a second edition, revised and enlarged, was printed in 1966.

As the logical outgrowth of this collection, the growing interest in Nauvoo because of the work on Nauvoo Restoration, Incorporated, which was established in 1962, and the inadequacy of research on this important phase of U.S. history, the library decided to sponsor a conference on “The Mormons in Early Illinois.” At this conference, held May 11, 1968, eight papers were presented—six of which make up this special section in Dialogue. I served as Conference Chairman and the three sessions were chaired by William K. Aldefer, Illinois State Historian; Richard S. Brownlee, Director, State Historical Society of Missouri; and John Francis McDermott, Research Professor, Humanities Division, Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville. In addition, a special exhibit, “Old Buildings of Nauvoo: A Photographic Report,” by Harold Allen, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, was displayed.

The object of the conference was to bring together the best available scholars in and out of Mormon circles to present papers on topics of their own choice. No “problem” or special theme was selected; the emphasis, rather, was placed on non-partisan papers based on new research in primary sources.

Collectively, however, the papers are much more than an interesting potpourri. A theme of sorts—”Were the Nauvoo Mormons really Ameri cans?”—did emerge and was developed mainly through the analysis of Nauvoo politics, recent historiography, and mid-nineteenth-century fiction. The following are some of the questions which were raised by the conference. What was primitive Mormonism? Why was there such intense hatred of the Mormons? Why was most early literature on the Mormons produced by hack writers? What is the trend and quality of current literature on the Mormons? Why was the search for identity by the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints so protracted?

The papers presented here were written by scholars of different religious persuasions and academic backgrounds and reflect different approaches—i.e., historical, cultural, economic, political, and bibliographic. Understandably (and fortunately) the authors do not always agree with one another in interpretation. Flanders, for example, considers the Mormons to have been true Americans—”Jacksonian entrepreneurs”—a position that Bushman does not hold. Most of the conclusions are given in a tentative tone and the authors invite further scholarly study and analysis of the many unused or inadequately used primary sources. The existence of the microfilm collection at Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville, should greatly abet future study of the Mormons in Illinois.

I would like to thank Robert MacVicar, former Vice-President of Aca demic Affairs at Southern Illinois University, for support in making the conference possible. I also thank John C. Abbott, Director of the Lovejoy Library at Southern Illinois University (and a contributor to this section) for his sustained interest and encouragement in relation to the collection and the conference. And I am grateful to the S.I.U. Office of Research and Projects for their assistance. Finally, the contributors and I are grateful to the editors of Dialogue for their willingness to publish the papers and illustrations in this special issue.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue