Articles/Essays – Volume 39, No. 4

Maturing and Enduring: Dialogue and Its Readers after Forty Years

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Introduction

Just about twenty years ago, the editors of Dialogue commissioned a general survey of subscribers. The results were published in its spring 1987 issue under the title, “The Unfettered Faithful,” intended to evoke an image of religiously committed readers who felt free to explore the issues and frontiers of Mormon thought beyond the conventional treatments in official Church literature. The purpose of this article is partly to replicate and compare more recent survey results with the earlier ones. Our title refers not only to the “maturing and enduring” of our faithful readers (two-thirds of whom are now older than fifty), but also to the same developments in the journal itself, which has passed through many editorial hands and has survived more than one period of crisis in its forty-year history, even in recent years. Another purpose for this article is to provide both a descriptive and an analytical overview of the traits and interests of Dialogue readers at the opening of a new century, at least as indicated by those readers who responded to our survey.

The earlier survey was conducted entirely by mail during 1984. The database at that time included approximately 2,900 names, of whom four-fifths (2,300) were current subscribers and the rest recently lapsed. Persistent follow-up efforts produced an eventual return rate of about 60 percent of that database (-1,800), with no appreciable bias perceptible from nonresponse, except for an underrepresentation of Utah subscribers and of women. This survey was conducted during 2005 with a database of about 3,500, but this time including only about half that many current subscribers, plus another 300 whose subscriptions had lapsed recently. The rest were long-term lapsers or customers who had purchased something from Dialogue but had never subscribed.

Respondents this time were given the option of sending back paper questionnaires by mail or taking the survey on the Dialogue website. Despite strenuous follow-up efforts, the return rate this time reached only 50 percent among current subscribers and about 30 percent among lapsed subscribers and others. Of those who did respond, three-fourths used the mail-back option, and one-fourth used the internet. Nonresponse bias was again apparent from the underrepresentation of women, probably because the addresses we had were in the husband’s name for most of the households. Altogether, from the entire database and from both mail and internet respondents of all kinds, we received 1,332 usable questionnaires. On the whole, a question-by-question comparison between the 1984 and the 2005 surveys shows surprisingly few differences on a percent age basis. We will point out some similarities and differences as we go along.

Respondent Type and Results

Since respondents were of different kinds (current subscribers and otherwise) and had responded in different ways, we wondered whether our results had been affected by any of three factors distinguishing the respondent types: (1) whether the respondents who took the survey electronically (via our website) answered the questions differently from those who responded on paper by mail; (2) whether the respondents who were lapsed subscribers answered the questions differently from those who were current subscribers; and (3) whether those who were long-term subscribers responded differently from those who were more recent subscribers. Comparisons of these three kinds determined that, on the whole, no statistically significant differences appeared in the responses to the various questions. There were, however, a few exceptions to the “no differences” generalization:

1. As might be expected, those who responded to the survey through the Dialogue website were noticeably younger, in general, than those who responded by mail. They were also more likely to be male and returned missionaries, but somewhat less inclined than mail-in respondents to be orthodox in their beliefs about the Book of Mormon and about how to deal with Church policies with which they disagreed.

2. Lapsed subscribers, when compared to current subscribers, were considerably less likely also to be regular readers of other LDS-related publications (e.g., Sunstone, the Ensign, Journal of Mormon History), so it is not that they have been replacing Dialogue with this other reading. Lapsers were also somewhat more likely than others to be female and to be in their middle years (ages 31-50), when many of life’s stresses seem greatest; but somewhat less likely (60 percent vs. 72 percent) to regard Dialogues tone and content as objective and independent; or to say that Dialogue contributed to their spiritual experience.

3. The length of subscription among all respondents, was positively correlated with age, sex (male), and educational attainment. Also, shorter-term subscribers were more likely than longer-term ones to visit the Dialogue website; to prefer issues of Dialogue devoted to single themes (as opposed to varied content); and to be interested in downloading individual articles. Short-termers were less likely, however, to be readers of other LDS-related publications, or to find “most” enjoyable the personal essays, book reviews, and letters published in Dialogue. In response to the question about how they had first learned of Dialogue, most cited friends and family members, no matter how long they had been subscribers. A surprising number of subscribers, however, under “Other,” wrote that they had first learned about Dialogue from classmates in LDS institutes, at BYU, or at other colleges. Only “charter” subscribers in any numbers (20 percent) cited “advertisements” as their first contact with Dialogue—referring perhaps to the start-up ads circulated in 1965.

These few differences in responses by subscriber type are not of the kind or magnitude that might make it difficult to generalize about what sorts of people read Dialogue. Let us begin, then, with a fairly high level of generalization: the modal reader.

If responses to our questions were not much affected by currency or recency of subscription, or by paper vs. electronic response to the questionnaire, then how might we generalize about our subscribers? What other characteristics would go into a “portrait” of the most common kind of Dialogue subscriber today (at least, among those who responded to our questionnaire)? The modal respondent is a home-owning, married man over age fifty with a post-graduate degree. He is either in retirement or approaching it, resides in either Utah or California, is a life-long member of the LDS Church and a returned missionary, and attends sacrament meeting virtually every week. He regularly reads the Ensign and many other religion-oriented publications besides Dialogue. He has subscribed to Dialogue for at least ten years, reads half or more of every issue, finds the editorial tone and content of Dialogue to be generally objective, and feels that the journal contributes to his spiritual and religious growth. He is inclined to be supportive of Church programs and policies, although he might express some dissent privately to leaders before going along; and he regards the Book of Mormon as a divinely inspired document, even if it is not literal history.

Demographic Traits of Readers

About three-fourths of our respondents were men (perhaps an artifact of patrilineal household addresses). This is the same proportion as we found in our 1984 survey. Some 81 percent of our readers are married, again the same proportion as in that earlier survey. Other marital categories were also about the same.

We are not surprised to see that most of our readers are relatively old. About 64 percent are over age fifty (more than 40 percent are over sixty). Almost exactly the same total proportion (60 percent) was between ages thirty and fifty in our earlier survey. These are probably the same people, in large part, but just twenty years older, so we are still not reaching many in the younger half of the age range, especially those below age forty (only 17 percent now compared to more than 40 percent in the earlier survey).

In our earlier survey, 55 percent of our readers lived in the western states (Rockies to the Pacific Coast), and all the rest were scattered elsewhere. Now 72 percent are in the western states (including 33 percent in Utah and 17 percent in California—i.e., half of all respondents). The rest are scattered around the country, with some 10-12 percent now found in the Northeast. Fewer than 1 percent are in the rest of the world combined.

Dialogue readers have always been well-educated. Some 41 percent have doctoral degrees (about the same as in the earlier survey), and 31 percent claim master’s degrees, up from 26 percent earlier. The proportion with bachelor’s degrees is now 21 percent (similar to the 1984 figure of 25 percent), but readers with no college degree are fairly scarce (now 8 percent vs. 12 percent earlier).

Home ownership is up a bit (90 percent vs. 82 percent earlier), probably a function of the aging of the readership. The proportions of respondents who are self-employed and those who work for others have both declined, while the retired fraction has gone up to one-fourth—obviously a function of aging. Sixty-four percent remain in the work world, and the rest are homemakers or otherwise engaged. Only 2.5 percent of our readers are students.

Variable Levels of Commitment to Dialogue

Maintaining Subscriptions

There has not been much change between the two surveys in how long respondents have had subscriptions. A third have subscribed for less than ten years, another third for twenty-five years or more, and a final third in between. One in six respondents is still a charter subscriber. Our newest subscribers (< 4 years) account for more than a fourth of the total, so our marketing efforts seem relatively effective, though this figure is a little lower than that reported in the 1984 survey.

In that survey, only 14 percent reported that their subscriptions had lapsed. Today about a third of the respondents admit that their subscriptions have lapsed, for longer or shorter periods. We asked them to write their reasons. Studying these has led us to conclude that most of the reasons are simply pretexts that could be neutralized through skillful promotion and marketing, rather than serious explanations for lapsed subscriptions. For example, a common complaint was a lack of time or money to keep up on the reading; this reason reflects priorities in subscribers’ lives rather than disaffection with the journal. Other common reasons include a loss of interest in LDS matters generally, or in the Church itself, due to changed outlooks across time and life-stages. Quite a few blamed “circumstances” or their own negligence for the lapsed subscriptions, suggesting the continuing need for proactive follow-up on lapsers.

Subscriptions have not increased for more than a decade. Throughout most of its history, Dialogue (like similar journals) has suffered an annual nonrenewal rate of 10-20 percent, which must be replaced with new subscribers if the journal is to survive. It is only the time, energy, and initiative of our business director that have enabled Dialogue subscription levels to remain fairly stable (between 1,700 and 2,000) in recent years. The increasing online access to all such journals is likely to undermine even further the appeal of printed copies, so it is a constant struggle even to maintain subscriptions, let alone increase them whenever possible.

When we get new subscribers, they tend to come from about the same sources as twenty years ago. Some 57 percent report having been referred by family members, relatives, or friends, compared to 61 percent in the earlier survey. This figure suggests the need for special marketing efforts with current subscribers to get them to help recruit friends and relatives.

Reader Satisfaction

Sixty-nine percent of our respondents claim to read half or more of each issue of Dialogue, but they don’t share it with others as frequently as respondents did in 1984. At that time, only a third of the readers failed to share their copies of the journal with others; but now the figure is over half. That might mean that the more possessive subscribers are inadvertently forcing others to get their own subscriptions; however, that does not seem to be the case. Among married subscribers, only 44 percent of the men share their copies with one or more others (presumably including their wives), while 60 percent of the women share theirs.

More than two-thirds of the respondents regard the content and editorial tone of the journal to be “objective and independent,” while another 15 percent find that the tone and content seem to vary with the topic under discussion. Only 10 percent judged the tone “negative and hypercritical,” but a near-matching 8 percent found it “bland and uncritical.” This distribution of responses was very close to the same in the earlier survey, an interesting consistency in reader judgment across time. Those respondents who chose to amplify their choices with comments generally seemed to understand that tone and content are bound to vary across time and topic. Perceptions about tone and content, furthermore, did not vary much by age or education level. Church attendance did not influence the “objective” verdict very much, but the “negative and hypercritical” opinion was noticeably higher among those who attend LDS services regularly (12 percent) than among those who do not (2 percent).

A few readers felt strongly enough about tone and content to record personal peeves. These comments were far more likely to express irritation over negative and hypercritical elements perceived in the reading of Dialogue than over bland and uncritical qualities. Elaborations written in for other questions, too (e.g., “what would you most want to change if you were editor,” and “what would you try hardest to keep the same”), constantly stressed the importance of fairness, balance, openness to varied viewpoints, and the like, while also objecting to articles that seem negative and hypercritical about the Church. The latter objection occurred three or four times as often as comments calling for more pointed or “courageous” criticism of the Church. Aside from tone, the write-in responses also complained fairly often that some of the articles were too academic, technical, or over the heads of readers.

Another indication of reader satisfaction is found in the responses to whether Dialogue “contributes to the enrichment of my personal religious or spiritual experience.” A decisive 82 percent agreed, either strongly or somewhat, again an interesting consistency with the 89 percent in the 1984 survey. This feeling about Dialogue‘s impact on spiritual life was not related to age, education, geographic location, or mission experience, but it was a little more likely among women than men and among regular church-goers. An unusually large number of respondents also wrote comments on this topic, the overwhelming majority being elaborations on the “agree” responses—some of them virtual “testimonies” about Dialogue’s effect on their spiritual growth. On the other hand, the main purpose for elaborating on a “disagree” response was to take issue with what seemed to be the premise of the question, namely that Dialogue was supposed to enrich personal spiritual experience. That is, disagreeing respondents were not particularly unhappy with Dialogue but simply did not think readers should expect a spiritual experience from it—only an intellectual one. Interestingly enough, this kind of comment came both from non-LDS (or ex-LDS) readers and from devoutly LDS readers, who simply thought readers should look elsewhere for their spiritual nourishment. Nearly half reported using Dialogue material, at least occasionally, in the Church classes they teach.

Preferences of Dialogue Readers in General

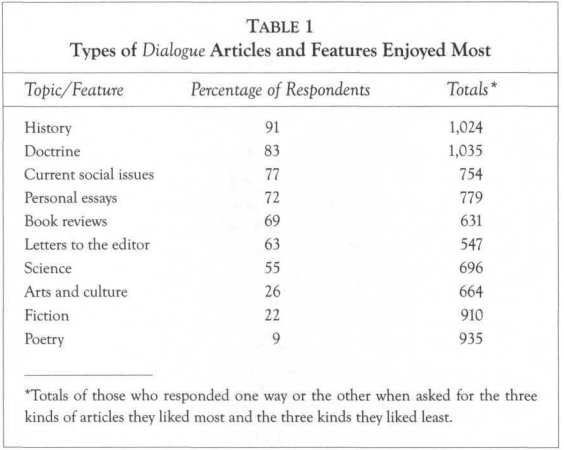

It is remarkable to see the stability of readers’ preferences in Dialogue content across the past twenty years. When we compare their rank-ordering of “most” and “least” favorite topics then and now, the figures are almost identical. They still show rather strong preferences for articles on history, doctrine, and current social issues, though with some drop in the last category. They like personal essays, book reviews, and letters to the editor. They look with considerably less favor on poetry, fiction, and articles dealing with the arts. (See Table 1.)

[Editor’s Note: For Table 1: Types of Dialogue Articles and Features Enjoyed Most, see PDF below, p. 89]

Two-thirds of the respondents, in 2005 as in 1984, prefer varied content rather than issues devoted entirely to one topic. However, 87 percent, the single strongest preference, is for issues containing small clusters of articles on a given theme or topic. At the same time, there appears to be some interest in future books made up of collections of articles on common topics or themes, taken from back issues of the journal. (Write-in suggestions especially identified history, doctrine, and social issues as favored topics for such anthologies.) There might be a marketing opportunity here for small print-runs of thematic books. Half of the readers said that they would buy such topical books (of reprinted articles), even if they could download their own copies of individual articles from the Dialogue DVD or website.

Other Mormon-Oriented Subscriptions

Readers of Dialogue read fairly broadly in other Mormon-related publications. Two-thirds (68 percent) reported subscribing to (or regularly reading) the Ensign (compared to 77 percent in the earlier survey). Other literature published under LDS Church and/or BYU auspices, and consulted by our readers, include BYU Studies (29 percent vs. 34 percent earlier); Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (17 percent); and FARMS Review of Books (13 percent). The last two, of course, were only just getting started twenty years ago.

In the “unsponsored” sector, the biggest overlap occurs with Sunstone, which is regularly read and/or subscribed to by 68 percent of our Dialogue readers (up from 60 percent in 1984). A fourth of our subscribers also get the Journal of Mormon History (25 percent, up from 20 percent earlier). Thus, Dialogue seems to have benefited mutually from our various collaborations with Sunstone and the Mormon History Association. Our readers also subscribe to the Utah Historical Quarterly (13 percent, down from 18 percent earlier), the John Whitmer Historical Association Journal (9 percent, scarcely read earlier), Irreantum (the AML journal—9 percent, scarcely read earlier), and the electronic FAIR Journal (6 percent, nonexistent earlier). However, in the case of Exponent U, only 17 percent of our readers report subscribing, down from 43 percent in the earlier survey, a drop perhaps attributable to editorial difficulties in maintaining a regular publication schedule at Exponent II.

Besides the list of Mormon-related journals and magazines provided for readers to check off in responding to this question, the survey invited them also to write in lists of “Other” periodicals that they were regularly reading. Unfortunately, the question did not specify that it was referring to “Other” literature of a religious kind, so respondents listed an enormous variety of periodicals of all kinds, professional and popular, religious, political, social, literary, and even hobby-related. The religious periodicals they wrote in included some of the newer Mormon-related ones (e.g., Mormon Historical Journal) as well as non-Mormon (e.g., Christianity Today). A number of electronic journals or sites were also listed (e.g., Meridian, Times & Seasons). Dialogue readers are especially focused on religion, but clearly they are widely read in many other fields as well.

Readers Preferences: Variations by Age and Sex

Age Differences

Age and length of subscription are obviously somewhat related, so correlations of responses by subscriber longevity often track those related to age. However, neither age nor subscription length produced many important differences in how respondents answered the survey questions. For example, age was not a factor in readers’ perceptions about the tone and content of Dialogue or about the influence of the journal on their personal spiritual experience. In reader preferences, though, younger readers did not favor personal essays and book reviews as much as older readers did. The older the readers, the more likely they were to enjoy letters to the editor, but the less likely to enjoy fiction. Otherwise, age made little difference in such preferences. (See Table 2.)

[Editor’s Note: For Table 2: Percentage of Dialogue Content Preferences by Subscriber Age, see PDF below, p. 91]

A positive correlation appeared between age and the number of other religion-related periodicals to which readers subscribed—perhaps a simple function of financial resources. We wondered, however, if the kind of journal to which readers subscribed (besides Dialogue) might differ ac cording to age. To examine this possibility, we first divided the other journals into (1) faith-promoting (Ensign, Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, FARMS Review of Books, and FAIR Journal; (2) neutral (Journal of Mormon History, Utah Historical Quarterly, Irreantum, and AM CAP Journal); and (3) “edgy,” meaning somewhat adventurous intellectually (e.g., Sunstone and feminist publications). This rank-ordered trichotomy was definitely correlated with age, but in a surprising way. The older the respondents, the less likely they were to subscribe only to periodicals in the faith-promoting category (see Table 3, row 1), and the more likely they were to subscribe to all three kinds including those in the “edgy” category (row 3). Otherwise, age made little difference.

[For Table 3: Percentage of “Other” Subscriptions Correlated to Age and Table 4: Dialogue Content Preferences by Sex, see PDF below, p. 92]

Our younger readers were somewhat less likely to live in Utah, more likely to live in the northeastern United States, and more likely to be fe male than were older respondents. They were also far more likely to have responded to the questionnaire electronically and to have visited the Dialogue website frequently. These differences by age suggest that a different “profile” for Dialogue readers will emerge after another twenty years.

Differences by Sex

Sex is more closely correlated to respondent preferences than is age. Women seem to share men’s strong interest in history, doctrine, and book reviews, but not by such large margins; they are much less interested in science. However, women are far more interested than men in personal essays, fiction, poetry, and the arts, and even more interested than men in current social issues. (See Table 4.)

Men and women were not very different in their judgments about the tone and content of Dialogue. By large margins, both sexes found the articles generally objective and independent; but men were twice as likely as women (11 percent vs. 6 percent) to find Dialogue hypercritical and negative. Nor did men and women differ much in their belief (by 80 percent or more) that Dialogue has contributed to their personal spiritual experience, but women were somewhat less likely to use its articles in preparing Church lessons or talks, perhaps, we hypothesized, because their teaching assignments more often involve youth or children. As for their tastes in other LDS-related literature (faith-promoting, neutral, or edgy), men and women did not differ to any significant extent.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 5: Frequency of Attendance at Religious Services, All Respondents, LDS and Others, see PDF below, p. 94]

Finally, women were more likely than men (a third vs. a quarter) to have been short-term subscribers (< 4 years), and a little more likely to have let their subscriptions lapse (41 percent vs. 32 percent). Both men and women are likely to read half or more of each issue, but women were more likely to share their copies with others (53 percent vs. 41 percent). Women are more likely than men (two thirds vs. half) to have first learned about Dialogue from personal contacts.

Religious Commitment and Its Implications for Dialogue Readers

Basic Indicators of Religious Commitment

Fully 90 percent of our readers are Latter-day Saints, mostly “lifers” but including 11 percent who are converts. The 1984 figure was 94 percent. Some 6-7 percent of respondents described themselves as no longer affiliated with the LDS Church. Most of these are now affiliated with other denominations. Only seven readers (not 7 percent) are members of the Community of Christ (formerly Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints).

Of today’s respondents, 67 percent attend LDS services every week and another 11 percent attend “most weeks.” This total of 78 percent is down from the 88 percent in 1984 for all respondents, LDS and otherwise. Also, 61 percent of today’s LDS readers are returned missionaries, a question not asked in the earlier survey. Interestingly, however, 41 percent of even the non-Mormons (probably former Mormons) also served LDS missions. (See Table 5.)

Today’s Dialogue readers are somewhat less docile than earlier readers in their attitude toward the LDS Church and its truth claims, though the differences are perhaps less than we might expect from the publicity given to dissenters in recent years. When asked what a Church member should do “when faced with a Church policy or program with which he or she does not agree,” 9 percent responded that a member should accept the Church position and try to comply (compared to 10 percent twenty years ago). Thirty percent agreed with the next response category: “express your feelings to leaders but then go along,” down from 37 percent in 1984. The total of these two categories together (“accept and comply,” plus “express disagreement but comply”), produces a category that might be called “supportive” (39 percent), down from 47 percent in the 1984 survey. The other categories, indicative of more serious dissent (“dissent privately” and “gather support from others”), are higher than the same responses in 1984: a combined 28 percent then, 44 percent now. Written comments usually said something like “it depends on the situation” or were mixtures of two or more of the four standard responses. (See Table 6.)

[Editor’s Note: For Table 6: Preferred Action When Disagreeing with a Church Policy, see PDF below, p. 95]

The past twenty years have also seen some decline in Dialogue respondents’ acceptance of the traditional LDS claims about the Book of Mormon. The 1984 survey asked whether the Book of Mormon is “authentic in any sense”; 94 percent said “yes.” The figure from the current survey is also 94 percent but in a more complicated way. Both surveys asked the “yes” respondents to identify “in what sense” they regarded the book as “authentic.” Interestingly enough, more responded to this question about the kind of “authenticity” than had responded “yes” in the first instance, suggesting that some of those who said “no” still found the Book of Mormon “authentic” by some definition. To accommodate respondents who said “no” but then identified the Book of Mormon as authentic in one of the categories, we reclassified some of those responses, bringing the “yes” total to 94 percent.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 7: Beliefs about the Book of Mormon, see PDF below, p. 96]

The interesting shift, however, is the kind of authenticity attributed to the Book of Mormon. In 1984, 63 percent gave the orthodox answer that the Book of Mormon is a literal historical record; the current figure is 36 percent (41 percent for LDS only). In other words, the percentage of those who accept the literal historicity of the Book of Mormon has de creased; current respondents are more likely to have a less literal understanding while still accepting the book’s authenticity. Twenty-three percent of current respondents agreed with the statement: “Its historicity might be doubtful, but its theology and moral teachings are of divine origin.” Only 14 percent had checked that answer in 1984, a noteworthy difference. In 1984, 77 percent of respondents were in the first two categories combined (literal historical record plus perhaps not historical but with divine theology and moral teachings). Now the combined figure is 59 percent. The next category was: Its moral teachings are sound and pleasing to God (10 percent then, 13 percent now), followed by the fourth category of authenticity: not divine but rather an authentic nineteenth-century product (7 percent then, 15 percent now). (See Table 7.) Another 7 percent of current respondents agreed that it was authentic “in other ways”—mainly restatements or minor qualifications of the four basic choices.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 8: Church Attendance by Book of Mormon Beliefs, see PDF below, p. 97]

No doubt the outpouring of scholarly literature on the Book of Mormon during the past twenty years (whether apologetic or critical) has influenced these figures. Some 70 percent of our readers acknowledged that such literature has influenced them “a great deal” or “somewhat” in their views on the Book of Mormon. The survey asked readers who answered “no” (did not consider the Book of Mormon “authentic in any sense”) to offer their own explanations for the book’s origin and contents. The written responses often conflated these two issues, but the most common explanation was Joseph Smith’s own imagination, while the second most common response was, in effect, “I have no idea.” Nonbelievers tended to explain the book’s contents as nineteenth-century ideas taken from Smith’s environment, fraud, or plagiarism (though with no clear idea about the specific source of the plagiarism).

As indicated in Table 8, however, a more “relaxed” definition of Book of Mormon “authenticity,” from literal history to simply divinely inspired scripture, is apparently not associated with a significant decline in Church activity. Attendance weekly or more often is characteristic of 81 percent even of those who hold this less orthodox view. Combining “weekly or more” attendance with those who attend “most weeks” yields a total of 93 percent of readers in this category (“divine origin”), virtually the same as for those holding to the traditional “literal history” view (97 percent combined). Indeed, a majority (59 percent) even of those who attribute no divine origin to the Book of Mormon claim regular Church attendance.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 9: Dialogue Respondents on a Composite Scale of Religious Commitment, see PDF below, p. 98]

Religious Commitment and Demographic Variations

Religious commitment might be defined in many different ways, but our questionnaire permits us to define it only operationally and in terms of only three components: Church attendance, acceptance of Church policies, and beliefs about the Book of Mormon. However, rather than attempting to measure the impact of each of these three commitment indicators separately, we have combined them into an additive and scaled index to create a composite Scale of Religious Commitment that cumulatively takes into account the respective weights of each indicator. Thus, the more “orthodox” a person is on each indicator, the higher will be his or her religious commitment score. Table 9 displays the distribution of respondents on this scale.

Measured on this scale, a third of our respondents (32 percent) occupy a middle category of religious commitment, but half are in the two highest categories (total of 47 percent). We discovered, furthermore, that this general distribution is only slightly affected by some demographic factors, but not nearly so much by age as one might suspect. Table 10 shows that religious commitment rises in about the same pattern in all age groups (columns). The youngest age group has the largest percentage of any groups reaching the “most” committed category (37 percent), but otherwise there is really very little difference across these distributions by age.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 10: Percentages of Religious Commitment by Age, see PDF below, p. 99]

Education level, sex, and marital status made little difference in religious commitment. Residents of Utah and of the midwestern states appeared in the two highest levels of religious commitment more often than did readers from other areas. Not surprisingly, LDS members, and especially returned missionaries, were the most likely to appear at the highest levels of religious commitment, while non-LDS, reaffiliated, and ex-LDS readers were most likely to appear at the lowest levels—an obvious artifact of the particular operational definition and measurement of religious commitment used in this particular study.

Influence of Religious Commitment on Reader Preferences

Religious commitment obviously matters a great deal in the lives of LDS members generally, but applying our Scale of Religious Commitment to various questionnaire responses revealed little or no difference in many of the responses. For example, in respondent preferences for topics in Dialogue articles (history, doctrine, science, etc.), religious commitment did not distinguish much among readers. In Table 11, however, reader attitudes toward Dialogue’s “tone and content” were correlated with religious commitment. At least half of the most highly committed experienced Dialogue as “objective and independent,” but a fourth of this group found it “hypercritical and negative.” In contrast, three-fourths of the least highly committed found the journal “objective and independent,” while a fifth found it “uncritical and bland.” In general, the “objective and independent” verdict declined with increased religious commitment. However, this trend was offset somewhat by the positive correlation between religious commitment and “depends on the topic.”

[Editor’s Note: For Table 11: Perceptions of Dialogue Tone and Content by Religious Commitment, see PDF below, p. 100]

As already observed earlier, readers in general find that Dialogue contributes to their spiritual and religious experience, a perception that increases with religious commitment, but more in the middle ranges of commitment than at the highest level. The same general pattern appears in using Dialogue lessons and talks. Not quite half of the most highly committed report such uses of Dialogue, but more than half in the middle ranges do so, while very few at the lowest end of the religious commitment scale do. This pattern suggests the interesting implication that appreciation for the spiritual contribution made by Dialogue to religious life is even greater among readers with moderate-to-strong religious commitment than among the most strongly committed.

A certain wariness about resorting to “extra-curricular” reading material among the most highly committed can be seen also in their relative lack of exposure to the recent scholarly and scientific literature on the Book of Mormon, which most of them report has influenced them “slightly or not at all” in their understanding of that book of scripture. In contrast, 52 percent of the least highly committed report “a great deal” of influence from such literature.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 12: Use of Other Mormon-Related Literature by Church Commitment, see PDF below, p. 101]

The same wariness among the most highly committed can be seen in their “other” religious subscriptions. They were the most likely to subscribe exclusively to periodicals of the “faith-promoting” variety, while the least highly committed were, as expected, the most likely to take “edgy” journals. Actually, however, most Dialogue readers were very eclectic in their preferences for this “other” literature. The largest category of choice among the entire range of religiosity was the middle or “most mixed” combination. (See Table 12.)

Implications of the 2005 Survey

Our readers are (perhaps not surprisingly) quite homogeneous in their intellectual outlooks and reading tastes, as the description of the “modal” Dialogue reader shows. Demographic differences, such as age, sex, education level, region of residence, and even frequency of Church attendance generally make relatively little difference in the intellectual outlooks of our readers. Compared with the 1984 survey, this fairly homogeneous readership seems to have remained quite stable for decades. It might therefore be considered our base constituency. Any strategy adopted to increase circulation of the journal should perhaps look first and foremost at new potential subscribers with a similar profile. Any broadening of that profile should probably be sought mainly at the margins. Marketing efforts should always take account of the likely impact of any promotional or editorial strategy upon that base constituency, lest outreach efforts to very different kinds of readers jeopardize the loyalty of the existing base.

The relative homogeneity of this base constituency includes a fairly devout attitude toward Mormonism, though perhaps more of a “Liahona” type of Mormon than an “Iron Rod” type. Elements of this attitude include embracing the essential divinity of the Book of Mormon, if not its literal historicity; attending church regularly; and generally supporting—or at least accepting—questionable Church policies and programs, even if with reservations. This outlook, however, does not condone actions or publications that are perceived as attacking the Church or scorning its truth-claims. A rejection of the negative and hypercritical came through again and again in the open-ended comments written by respondents on their questionnaires—and at a far higher frequency than the opposite kind of comment—namely, complaints that Dialogue had lost its “critical edge” and become too bland.

Readers are not looking to Dialogue as a substitute for the Ensign, to which the great majority of them already subscribe; but neither are they seeking a vehicle to reform the Church or update its doctrines and policies. Our readers expect and want treatments of difficult and controversial issues in LDS history, doctrine, and social life, but they want those treatments to be balanced, if not wholly “objective,” and they want more than one side of a controversy presented, preferably in the same issue of the journal. This characterization comes very close to a similar conclusion about the 1984 survey and for most of the same reasons, which, in turn, seems a close reflection of what Eugene England and his associates had in mind when they founded Dialogue forty years ago. We have, in other words, a tradition. Dialogue also has an established role in the broader LDS culture, described in positive terms even in the quasi-official Encyclopedia of Mormonism.

Unlike 1984, however, our subscriber base is now heavily skewed toward an older age. One reason, of course, is the aging of the founding generation. Another might be the loss of potential subscribers from the younger and middle age groups, who became wary about Dialogue and similar publications after admonitions by conservative Church leaders, starting in the early 1980s, became more pointed and sterner by the end of that decade. A third reason might be the more critical edge that became apparent in a few Dialogue articles during the 1990s and/or an inadequate program for maintaining and building subscriptions in the same general period. The print-run for issues by the end of 1987 had exceeded 5,000 (not all of which would have been for subscribers). About 1990, subscriptions began to fall and, by the end of that decade, stood at less than 2,000, where they have remained, more or less, ever since.

The younger age groups have been disproportionately affected by this drop-off. At present, only 4 percent of Dialogue subscribers are thirty or younger, compared to double that figure twenty years ago. Even those in the 30-40 age group account for only 12 percent (vs. 30 percent earlier). Subscribers in their 40s account for a fifth of our total (19 percent). Taken together, all of these younger age groups (20s, 30s, 40s) total 38 percent of our subscribers. The rest are over fifty. It is not at all clear why Dialogue has not been attracting younger readers with the same success that it attracted their parents’ generation. There seems no reason to believe that younger readers have different tastes and preferences from those of older readers in kinds of articles (see Table 2) or that younger readers are look ing for more “edgy” or adventurous articles (Table 4).

Somehow the students and other younger people among our potential subscribers must be attracted to Dialogue in larger numbers and convinced of the need to become and to remain as committed subscribers. They are crucially important to the survival of Dialogue, not only in the immediate future, but also because, in the long run, they are likely to become the well-educated and affluent supporters who will be able to keep Dialogue going as major donors, as editors, and as members of the board of directors. They need to take to heart the realization that without them and their resources, there simply will be no Dialogue to provide the rich trove of literature that they and their children will be expecting to depend upon.

Like other publications in the LDS “unsponsored sector,” Dialogue will always have to struggle to enlarge its subscriber base or even to maintain it. In this effort, minimizing subscriber attrition is at least as important as enlisting new subscribers. A comparison of lapsed subscribers with current ones indicates that the lapsers are somewhat more likely to be female, single, and middle-aged; to be reading less from any LDS-related publications; and less likely to find Dialogue articles “objective.” However, the “reasons” given by lapsed subscribers when asked to write them down did not, on the whole, reflect dissatisfaction with the journal as much as lack of time or money, their own negligence in failing to renew, or sometimes communication failures with the business office.

As for enlisting new subscribers, the questionnaire shows the importance of referrals from friends and relatives, a source that has consistently brought in about 60 percent of new subscribers. Ads in newspapers and magazines have never proved very effective, but relationships with Sunstone and the Journal of Mormon History prove to be good sources of potential new subscribers. For Dialogue to survive to the half-century mark, it will need the subscriptions and support of a lot more people, especially younger ones, from the “market niche” already reflected in its current subscriber base and from any others who see the value in what Dialogue offers. The board of directors and the editorial team, for their part, will need to remain constantly alert to cultivate and maintain a public image for Dialogue that bespeaks its tradition of religious and intellectual integrity, independence, openness, and balance.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue