Articles/Essays – Volume 03, No. 1

Mormon Architecture Today: The Lamps of Mormon Architecture, A Discussion

FERGUSON: Most Mormons are basically ignorant of architecture and the idea of architecture as much as they are ignorant of art and the idea of art, and there is no chance in the public schools for them to get that kind of education. The Church, although it sometimes says that it is a total statement of man’s environment, doesn’t make an effort to educate people in these matters. Maybe the place to begin long-term thinking is with educating the membership of the Church so that they will demand something more than they have now.

BERGSMA: I have always felt that to make people aware of good architecture and good design you should start with the home and household articles. (But perhaps in the L.D.S. Church, the chapel is where Mormons spend the most time.) It is like the old Scandinavian tradition. You have a beautiful cup and a beautiful saucer and a beautiful spoon and a beautiful rug and you live with it, and you are born wrapped in good taste. An awareness of handsome things becomes a part of the people. So I say that you don’t have to start at too high a level.

FERGUSON: When people find out that I am an architect they want to know my opinion of Church architecture, Church architects, the chapels that we are building, etc. Usually I give them a candid opinion, and they are surprised because I speak of things that they have never thought of before. It is not difficult to make some concepts very obvious to them, such as how one enters a building (Is there any real sense of entry?) or the relationship of the ever present recreation hall to the chapel or sanctuary. It just appalls and amazes me that most Mormons can go to the chapel day after day, week after week, and it never seems to dawn on them. I am almost sure it is because they have never found themselves in a great space or a great religious structure.

I agree that education is the process, but there are those of us who don’t want to wait until we are old and are hopeful that something else happens. We know how people get into a position where they can make a decision and how long it takes them to get to that position. Those of us who would like to see improved architecture have wondered if decisions about artistic matters might be made in some other way than through authoritarian direction from above.

SALISBURY: The only other way is to suggest a change in the theology.

MOLEN: I don’t think you have to change the theology. I think you have to point up the heresy—the absolute heresy—of building mediocrity.

I think you could point out that, after all, the Church did build the temple and they did take forty years building it and they had three different ways of getting stones down and all of the significance of this. Now we take one plan and we put it in the mountains and on plains and do all the terrible things that we have done with expandable plans, etc., and I think this could be obvious to many people. I think that this kind of thing has to be said in a very piercing, biting kind of way. SALISBURY: YOU are saying then that we’ve got an historical precedent that we can point out to our leaders, and this historical precedent is something they can understand because the buildings were constructed during the time that a lot of them were growing up.

MOLEN: Yes, we do have in the old buildings such valuable historical precedent, because much of the old is really quite good.

BERGSMA: There are two kinds of education. In one you can catch the young people and so the problem is solved for years to come, but then of course we want to do something now; so, get someone in authority and convert him. I am not being facetious when I say this. It is a reality. I think you all know it. I think you know that should someone in the Church office building tomorrow morning decide that great architecture is going to come from this Church, the rest of us would be running our fannies off trying to get it. Again, in the Utah Mormon circle you have a distinct advantage. If you educate everybody, in time they will all get the picture, but if you don’t they can be told; and once someone at 47 East South Temple decides to tell them, every community is going to not only preserve good things, but they are going to be careful, and they are going to grow in taste. If they don’t know what taste is, someone will make sure that they do because it has become part of the program.

MOLEN: What we have now is socialized architecture—we really do in every sense —bureaucratic, socialized architecture. And I think you could make a very clear case of this.

What is the difference really between what they are doing and what is being done in socialist countries (except that maybe the socialists have a lot sharper bureaucracy than we’ve got in the Building Department)? I think that we can make a really strong stand that this is violating principles that are the real foundation of the Church.

CHRISTENSEN: Practicality is a key here. The men who run the Church are in a sense like the men who run any big business; that is, they have a purpose and they gauge their success by how well they fulfill this purpose. In other words, the Church is attempting to spread its word to as many people as it can in the world and to change the lives of those people with its gospel. I think the brethren recognize the value of the Tabernacle Choir, for instance, because it has proselyting value. They can send it around the country and it advertises the Church. They can see its value.

The Church sees no value in good architecture. What’s the difference? You build a structure; you dedicate it; you hold your meetings in it; and where is the value? Now we have been talking about education. We’ve got to educate people to the value of good architecture in terms of the goals and the objectives of the Church. There is such a thing as bad environment, and there is such a thing as good environment, particularly for religious experience, and somehow we’ve got to get to them that this has value, that if they spend their money for this and spend the time and the interest, that it is going to pay dividends.

SALISBURY: You’re not completely right though. The Church has recognized the value of architecture. A year ago, the Improvement Era had a whole section on the new chapels that are being built in Europe and South America, praising them for their part in the proselyting effort.

CHRISTENSEN: You’re right, but goodness is equated with newness. If the paint smells new, the carpet is thick, the building is new and therefore good. This is not what we’re speaking of.

FERGUSON: I’d like to adjust a little bit what you’ve said, because I think funda mentally I would agree with you that there is something being neglected, but the Church is very much interested in good buildings, in roofs not leaking, in concrete foundations being adequate, in structural members being of the best quality they can afford and being properly built so that when an earthquake comes it doesn’t knock the building down.

They are interested in good building. They don’t seem to be interested in good architecture. I think it would be well to draw some distinction between what good building is and what good architecture is. The good building has to do with the new paint, the new carpet, etc., whereas good architecture has to do with environment, and what is terribly important to religious architecture—emotion.

What kind of an emotion should you evoke in a person through this religious structure that you build? What are legitimate forms for Mormon architecture, for Mormon chapels?

BERGSMA: Again I think that more than just talking one may go back, as someone mentioned, to history to show the values. The trouble with the Tabernacle is that not only is it a great building but it was a great building, which automatically makes anything on the same piece of ground great. My cross-campus students ask me every year about the Temple and you know you can’t say very good things about the Temple because it is just such a fantastic symbol. It is probably one of the greatest symbols you could create, but as architecture it is not very significant. Then when you tell them that the Church information building is a 1930 to 1939 style, I don’t think they understand that.

You’ve got to convert enough people to get someone to listen and then you’ve got to make a sacrifice to get something started. You can also quote, for example, a lot of things that were said about the Oakland Temple. The San Francisco papers were filled with the most vicious comments about the ugliness of the building and trying to get citizens groups to try to stop it because they said it was such an unpleasant looking birthday cake. Let the general membership see some of the criticism that was leveled against the Church via some of its architecture. And it can’t all be negative. I mean you’ve always got to balance it.

CHRISTENSEN: But when the people in the Church read about that very building, they read it in the Improvement Era. And what did it say—what a great building it was, when in fact it is not. Somewhere along the line Mormons have got to realize that most qualified people don’t believe that the Oakland Temple or the Salt Lake Bureau of Information are great buildings—they are merely eclectic architecture.

MOLEN: Many Mormons don’t think those are great buildings. Our own people are terribly distressed about the quality of our architecture. They ask, “Why are they all alike?” “Why are they all such funny looking things?” They are ashamed; they are embarrassed. A lot of people were humiliated by that thing in New York—the total insensitivity of making a World’s Fair Pavilion look like a temple. BERGSMA: Should anyone under any circumstances ever put up a fake temple, let alone half or part of a fake temple?

SALISBURY: Pop art. It was at least contemporary.

FERGUSON: Let’s get back to chapels. The potential of a Mormon Chapel is something really to get excited about in an architectural sense.

BERGSMA: I have only been in two ward houses and both of them were undistinguished and I’ve commented several times to groups of Mormons at firesides that I wouldn’t have felt much different in the chapel had I had a basketball in my lap. My comment basically was that I had no sense that I had arrived any place. I wasn’t in a gymnasium; it was definitely a ward house—I would have felt the same say, for example, if I had had a magazine in my lap. There was no religious connotation to the place. This is what has got to be conveyed to these people—that their chapel space is not religious.

CHRISTENSEN: Interestingly enough, it has been suggested that some of the University chapels are a little better than the regular ward houses, and one of the things they have done is to take that so-called cultural hall and move it away from the chapel so there is a chance for separation from this basketball type activity. In the average Mormon chapel, if the crowd is pretty good they open up the back wall and you’ve got your basketball court there; if you go into that same chapel on Tuesday night when they are having M.I.A., they do exactly what you are talking about. The kids run wild through there. How can they ever develop any sense of reverence?

SALISBURY: This is a big problem in the Church that we hear stressed repeatedly: reverence. The effort to achieve reverence has been going on for years and somehow people can’t link the two, the physical environment and the achievement of reverence.

MOLEN: Most Mormons want a chapel just like their living room, and that’s exactly what our chapels are like. They are carpeted. The very place they probably shouldn’t carpet. It ought to be a little more austere kind of place.

People are always complaining about reverence and I think this is a point that could be made—that people simply don’t recognize where they are because it isn’t a different place. It’s like every other living room, but it has a higher ceiling. It’s cozy and it’s so darn friendly that people just blab as soon as they get inside the door. Now, some people say this is good. It’s sort of a country club and they don’t want to change. On the other hand, the classrooms, that ought to be the warmest and most cheerful places, are the most austere, cold, white shells that you could ever put people in. Why would kids ever want to remember the classroom as a pleasant experience of an exchange between student and teacher, when really to most kids it’s just impossible to endure the place that long?

If we could compare all the breakthroughs that are being made in classroom architecture in what we call our primary and elementary schools and take some of that thinking, there is an awful lot of knowledge that we could apply. But we are not even thinking about it. There was an experiment in which they put rats in white cages and rats in colored cages with buttons to push, etc., and found that the rats in the more colorful, stimulating environment solved the rat mazes faster, etc. But we put all the kids in white cages and there is nothing memorable about a Sunday School class. There is nothing individual about it.

SALISBURY: A lot of people feel about our chapels like they do about our schools—that we spend too much money on them. Do better facilities really make for better learning?

MOLEN: The real answer is that if you had classrooms where people could really try to relax it might be better for communication, but real communication doesn’t occur. And a white shell with tin chairs is not the place for it to happen.

FERGUSON: There is a very powerful kind of symbolism in the Church having to do with light and if you read into the doctrines of the Church you frequently come upon the word light as a symbol of truth and goodness and God—”Truth and Light.” Just that one idea when applied to a chapel really gets me excited. MOLEN: It is more positive than a cross in pure symbolism.

FERGUSON: It has fantastic possibilities, but then I go to church on Sunday and if you don’t believe I am making sacrifices, I am, because I go to a chapel that has not a seed, not a trace of the use of light in a symbolic sense. There is a window and a brick panel and a window and a brick panel and a window and a brick panel.

BERGSMA: This is one of the strong things you can tie into if there is something that you can prove about the Mormon Church and its theology and its basic direction that relates to “light.” It’s hard to convey because people don’t know what light is, compared to windows and light. You’re talking about a spiritual quality—the essence of light as opposed to lightness.

Well, I would say that generally speaking the people who throw stones at Mormon religious architecture, who are non-Mormons, criticize the lack of continuity between what they understand as the Mormon faith, the Mormon principle, and the expression in the building. Therefore, if you could go to the Brethren and say, “Do we believe in these principles, and if so where are they in our buildings?” Or conversely, through the survey of these old buildings of the times in the past where you have done these things, “Why don’t we do it now?” These are the types of things I think are communicable as opposed to shouting or withdrawing or blackballing. It’s much like Ruskin’s “Seven Lamps of Architecture.” What are the principles or “lamps” that should guide, or be apparent in, Mormon Architecture?

May I ask you another thing? I have heard quite a bit about testimony. That you give testimony in the ward houses.

FERGUSON: That’s true. This then is another key: the importance of the spoken word as opposed to the importance of liturgy.

BERGSMA: I was a Lutheran for many years and on some occasions we used to have to give testimony, but you always saw everybody’s backs, and even as a youngster I used to think this was terrible—facing towards the minister and giving testimony. If testimony is that important, why isn’t there some way then that people can see.

Now these are the kinds of manifestations of truths of the Church that should have their manifestation in floor plan and form.

MOLEN: The human figure when standing should feel very much at home in the chapel, rather than having something so cathedral-like that it would be dwarfed. You can’t do what is being done by other churches. It’s got to be totally different.

FERGUSON: YOU go to a cathedral and you watch the drama, a liturgical drama created by the priest. He relates himself to the axis of the church as he puts his arms out and as he raises his staff and so on. It may be that you don’t agree with him, religiously, but you must admit that it’s a beautiful drama and this configuration, this axis—it means something. When you go into a Mormon building there is none of that. The axis is there and it looks a little bit stupid when what you really want is a feeling of brotherhood and the feeling of enclosure so that the spoken word can be heard and you can see a person’s face and you sit across from him. You know there is something about sitting across from a person rather than looking at the back of his head that allows you to feel more like a brother to him, I believe, and that really ought to be a part of the thing along with the light.

SALISBURY: That arrangement exists in the Tabernacle—in all of the old tabernacles around the state where there are seats around the side. You sit up in the gallery and you see so and so across the way, and there is more of a sense of participation than in our chapels today.

FERGUSON: That was a great thing.

BERGSMA: Now you’ve got two “lamps.” But what are other things that one can take right out of the Mormon scripture or out of the general scripture that you cannot just dismiss as unimportant but can point to and say, “Look, this building just doesn’t do it.”

FERGUSON: There is not a religion that I know of that teaches respect for an individual to the extent that Mormonism does, that you as an individual have always existed as an individual. There will never be another like you. You are unique in history and time.

SALISBURY: Which is a quality that makes us in a sense equal to God himself.

FERGUSON: Now if we truly appreciated individuality we would look for individual people to design individual chapels and appreciate the chapel as a statement of an individual.

BERGSMA: You could carry this one step further to the point that young people as a group on a college campus demand something different from a group in a farming community like Heber and demand something quite different from the middle class area of Kearns, which would demand something different than the upper class area of Federal Heights. But it could be that they should all be alike. This is another point to be considered.

CHRISTENSEN: This is certainly one valid point in opposition to the way the Church Building Department gives architects a set of plans and asks them to put their stamp on it instead of trying to solve an individual problem.

MOLEN: Another point is that we believe in the concept of continuous revelation—that God is always communicating with man. This also gives man the responsibility of saying something back to God, and what are we saying in our Churches? We are saying back the worst things possible. We are giving Him warehouses.

SALISBURY: Ten years ago we were giving Him back mediocre replicas of New England protestant churches, which is really great. He gives you a new revelation and you give Him back a leftover from the Reformation.

BERGSMA: I can give you one better than that and I use it in my class all the time: When the eclectic period arrived no one thought much about it, and I always show a picture of the Church Office building, copied directly from a pagan temple, but they don’t think a thing about it because the Catholics, the Presbyterians, and the Episcopalians have all used this pagan architecture.

What about baptism? Is it done in your chapels? If so, this is a meaningful part of the Church; I am looking for more “lamps” of Mormon architecture.

SALISBURY: Typically, a baptistry is built in conjunction with the gymnasium, so that a common dressing room can be used.

BERGSMA: Perhaps it should be void of dramatics. Maybe it is supposed to be common and ordinary.

FERGUSON: No. This is very important. You are supposed to prepare your children for it. This is the first step.

BERGSMA: If it is special, then it shouldn’t be treated like a second-rate thing.

SALISBURY: But we have the problem in Mormonism of having things special without letting them become ritual.

BERGSMA: Are you afraid of them ending up as worshipable things?

MOLEN: Right.

FERGUSON: We are iconoclastic—boy, are we iconoclastic.

MOLEN: And yet we have more symbolism than anybody else.

BERGSMA: But they had stained glass windows in the old ward houses, stained glass pictures of Christ.

FERGUSON: Well, another of these “Seven Lamps” that you are talking about I think would be the idea of truth. The Mormon idea is that truth is to be found everywhere and that we are to seek truths in everything. Now there is a truth in building. There is a truth in organizing spaces into the proper sequence.

SALISBURY: And a truth in the use of materials.

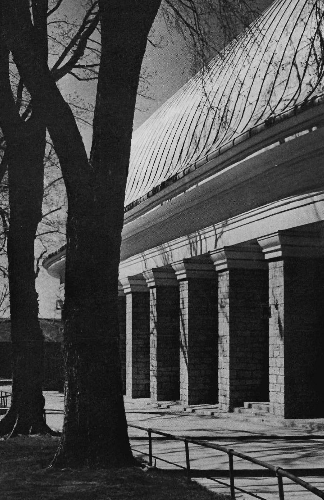

CHRISTENSEN: It has been said that secular architecture—barns, and so forth—is more truthful than religious architecture and that these structures are perhaps more religious than some of our so-called religious edifices. Along this line then is the fundamental fact that we are direct and truthful, and that’s why the Tabernacle is truthful, because it is direct in its use of materials and structural system.

BERGSMA: I am not trying to depreciate the point but to emphasize that it is difficult to convey in layman’s terms. We’ve got to get down to something which is tangible, such as the truth of related functions to one another, and that there is a truth of form that people might be able to understand.

FERGUSON: Well, there is another aspect to it too, and that is that there is truth in the experience of building, in the craftsmanship. There is something sacred to the true craftsman and the true artist about putting something together. Ron was speaking earlier of the chapels with carpets and paintings and so on, and I like to call that cosmetic architecture, because the thing goes together slam-bang and then you slurp on all of these coverings so that the true building, the building itself, is covered up with layer after layer of caulking and painting.

BERGSMA: Let’s get back to another point that is allied. What about permanence?

CHRISTENSEN: You build for eternity.

FERGUSON: No, you don’t worry about it because the millennium is upon us.

SALISBURY: But the theory is, you prepare yourself as though the millennium were tomorrow, but you build to last for a thousand years.

CHRISTENSEN: Speaking in terms of these “lamps,” eternity is certainly an important concept in Mormonism.

BERGSMA: But outsiders say, “How can it be such an eternal religion with such temporary buildings.” For example, look at the Temple. It looks eternal. There is something about it that is eternal. There is something about the Tabernacle, too, that has an eternal quality, that looks like it would last for one thousand years.

MOLEN: You know, though, as bad as Mormon architecture is, there is an awful lot of junk that is being built as church architecture.

BERGSMA: Yes. In every religion.

SALISBURY: Yes, but this is the true church.

BERGSMA: But the Catholic church has by far the most distinguished architecture of this generation.

FERGUSON: In my opinion, the best is in Europe. I think the best contemporary church architecture is being done in Germany and Switzerland.

MOLEN: And in Japan.

FERGUSON: Now maybe I should define what I think is good about them. In the first place, they are not cosmetic. You see what the building is made of and the materials are used in an honest way. Secondly, there is a structural system that is apparent. Thirdly, where liturgy is important it is used with an appropriate framework, and where the spoken word is important, it is made to be important.

BERGSMA: A religious building should be a work of art, the greatest thing that man is capable of giving back in terms of producing a beautiful thing. This is the old Catholic idea from the Gothic Age when communities were definitely trying to out-do their neighbors for the greater glory of God.

MOLEN: Nothing was too good. They were giving their very best.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue