Articles/Essays – Volume 23, No. 4

Of Pleasures and Palaces

(1961)

I sat waiting in the downstairs living room in the “House of Happiness” where only a correct, efficient, middle-aged nurse interrupted a grueling aura of lost wills, defeated pluck. The inmates, whose residence in the “House” indicated graduation from the central hospital, were considered either cured enough now to assume passive roles in organized society or sufficiently enfeebled to pose no more of a threat to nursely control than idiot children (“Time to take your pill, deary; Now . . . that’s a good girl!”).

The head nurse, whose educated cheerfulness assured me a text book welcome, had gone to fetch my Aunt Lois, whose transfer from the hospital to the “House” had coincided with my return home for a vacation, of the homecoming kind which a writer convinces himself is necessary every half-decade or so. And now I was to bring her home again, “completely cured,” the hospital officials had assured my father, by the marvels of modern therapy.

Waiting in the phantasmal silence, I watched the fingers of the older inmates pick at doilies while the younger and more mobile wandered from couch to rocking chair to window, often humming the substances of a fractured tune. Like lazy cats they searched out a patch of sunshine, a couch, a window curtain —lazy cats, clawless, purring harmony, quizzing the mystique of furniture with fixed and empty eyes.

Presently I felt the burn of eyes on the back of my neck, and turned. A stringy hawk-faced young woman lay curled like a fetus upon a couch, frowning me into focus. Spittle ran from her lower lip. She met my gaze with an idiot smile, then made a picket fence of her hand in front of her face. Her eyes, through the palisades, registered nothing as words stumbled through a guttural monotone:

“You wanta-see Loiey? Do ya? What for? Who you?” Her body uncoiled like a stiff rope, and she shuffled toward me, her arms rigid against her flanks. I scrambled to my feet and retreated to a conversational distance. But she staggered forward like a stunned boxer, her face looking up, her mouth close enough to my chin to bite it. She tapped a middle finger hard against my collar bone: “You Loiey’s boyfriend? If you him, you better git on out of here. Loiey, she don’t love you no more. Are ya? You Loiey’s lover? You better not.”

The nurse reappeared in the doorway. “Cynthia! Upstairs! Right this minute!” The command struck the woman like the whip that sends the tamed tiger back to his cage.

The nurse smiled professionally. “Sorry,” she said, dismissing the incident. “Your aunt will be here in a moment. She’s fixing up her room. I didn’t tell her who you are . . . thought she’d kind of enjoy the surprise.” Turning, she shouted up the stairs: “Loiey dear! Please hurry now! Don’t keep your gentleman waiting.” To me: “She’s so meticulous . . . sometimes takes an hour to make her bed. Every little wrinkle, you know. We’re so pleased with her behavior . . . so much better . . . we almost hate to see her leave us . . .”

Before I could utter the expected banalities, her eyes shot past my shoulder and she cried, “Uncle Billy!” I turned to see an old man methodically squeezing his crotch. “Come with nursey . . . hurry now!” She swept past me, pulled the dropsical old man from his chair and led him away, presumably to a bathroom. He followed like a bear on hind legs.

Soon the nurse reappeared, closely followed by an unbelievably fat, ugly woman whose only show of animation existed in the slow exercise of eyes which lay buried in face-flesh, like two small brown buttons in a mass of gelatin. I had no way of knowing, until first the child-nose, sharp and thin, then the legs, still slender, and then I remembered a Lois-echo from another time:

“Through the lightning and the thunder, and I wished so hard it would quit, Daddy’d hold me close and say through his beard: ‘Lois, my little Queen, what ever is to become of you . . . when I die!’ ”

Before I could speak, the nurse said, “Aren’t you the same one — ten, twelve years ago?” I nodded, my eyes fixed upon the still unknowing figure whose eyes had not yet registered recognition.

“I’ll just leave her with you,” the nurse said. “And when you’re ready you can sign the papers. Loiey dear, now be a good girl, won’t you? Your gentleman wants to be alone with you for a few moments.” She squeezed my aunt’s hand and left.

“Aunt Lois?” I said, my mouth brushing her ear and kissing her cheek. “Do you remember me? Your nephew—Carl’s son.”

Her eyes turned upon me slowly and a smile began to labor through the swollen flesh of her cheeks.

“This is roses—They’re growing beside a huge, huge river.”

“Why, why . . . Al-vin—is that you?” Her voice rose like a timid resurrection from the cemetery of silence —its assonance, like that of the deaf, a steady whine, without inflection. “It’s not really you —is it? Where have you been so long . . . ? Why dearest, what happened to your hair . . . ?” Her lips proved barely able to manipulate under the weight of flesh obstructing their movement. “Are you feeling well, dearest?” she whined. Her hand touched and retouched my face, like a beggar woman examining, wanting a mink coat. “You look awfully old, my dear . . . Oh, I’m all better now, you know . . . Did Nursey tell you? She’s nice. She says I’ll never have to go back to that dirty old hospital again. . . . Did you come to get me? She takes me to Sunday School every Sunday . . . I hope so because it’s been twenty years ago, you know . . . Did Nursey tell you? Except that awful time when your father . . . why did he hate me so much? I would have stayed home that time if he hadn’t hated me. And I pay my tithing too, every bit of it . . . I make five dollars a month doing the wash . . . but I’m awful tired and my back aches most all the time so you see I really do need a vacation .. . I pay the Church fifty cents a month . . .”

“Why don’t the lion lay down with the lamb? The lamb’s willing, I can tell you that!”

A good many ears had tuned in, and I saw Cynthia malingering at the top of the stairs, descending two steps at a time, in jerks, like the minute hand of an old grandfather clock.

“Let’s go out on the porch and talk,” I said. “Or maybe take a drive, or walk to the drugstore. Would you like that?”

“Walk?” she said stupidly. “Where is there to walk to?”

I led her outside. She followed as if groping through blind cellars. “I got my things all ready,” she said. “It’ll only take me a minute. I haven’t got very much . . . not very much at all.” The whine continued, barely connecting the wistful spaces between words.

Outside, I expected her step to brighten as I placed her hand against my arm. But she stumbled through the same endless cellars, dumb to the maples, the box elders, the brilliant Utah summer sunshine.

“Green Willow, let’s walk up to Pine Canyon and not anybody else but us. And build a campfire under Cemetery Rock with all those cliffs and all, and hawks floating around in the sky as free and pretty as you please, and the wind whooshing down slow then fast so it’s sort of cold but not too much and yelling across the gorge and getting a couple of echoes back from the cliffs. Just us: and whistling, or singing, or climbing a tree, and nobody to point a finger at us and say, ‘No/’ Let’s go there tomorrow . . . and take a lunch. Okay?”

***

(1949)

From the living room window I watched Dad’s car turn down the road and saw a thin figure in the back seat bobbing like a child arriving at the town parade. Before the car had stopped, the figure jumped out and shrieked theatrically into the dome of a summer Utah sky. It was Aunt Lois —back “home” at last.

I had been well coached and, in addition, had read my aunts’ and uncles’ letters in which they had discussed the sensitive matter of Dad’s trying to rehabilitate Aunt Lois. From these letters I was to understand that the family wanted to help their unfortunate sister just as much as Dad did, but they simply believed that taking her out of the state hospital now was not the best thing to do, either for her, for society, or for the family. The letters revealed other secrets too:

. . . I swear that everything she ever did or said turned into trouble with a capital T. . . since you didn’t have to live with her after father died and we moved to Logan, you can’t know her as well as we do . . . believe me, Carl, she was hell on wheels and all that you learned through hearsay I can confirm through experiences . . . Please understand, I am not condemning her —we all realize her predicament is not entirely her fault. She’s had her share of bad luck, but . . . and it may even be, as your letters have suggested, that since she is still comparatively young and her major misfortunes occurred over eight years ago, she might be able to take a place in society again. I can only say that I doubt she’s changed that much. . . . There are others to think of too. And what about your responsibility to the family as a whole? Is it worth reopening the family closet in full view of the families with whom we all spent our childhoods . . . ? Have you considered the welfare and possible embarrassment of your own family? What about Laura? And what about Alvin? Certainly, you can’t expect a mere college boy not to be influenced.

She raised her arms limply, in the manner of a ballet dancer, and sucked in a deep breath. She was lean, lean as wire, just as I remembered her when on special occasions we visited Grandma Simmon’s house in Logan during my childhood, and I listened impishly to the fragmented whispers of this most beautiful and wicked member of my father’s family.

I walked out to the porch and waited, watched her, watched Dad, saw the embarrassment and tension work over his face, felt thrill and fear work into the excitement of my own responsibility:

Remember, your mother and I will be working at the elevator, so whether Lois can be helped to live a useful life depends more on you than us. You’ll be with her most of the time. Now, I don’t expect you to take unreasonable abuse, but when she tries your patience, remember she has been in an institution for over eight years, and if only half of what she told me about conditions in that hospital is true—well, I just can’t live at peace with myself knowing that my own sister is subject to such humiliation. If we can’t help her now, she’ll probably have to stay there the rest of her life. Think of these things and be kind to her . . . study her diaries, study the letters from your aunts and uncles. Maybe the conditions described in them will piece together the whole picture and help you confront your tasks with understanding. You’re young, but I think you can be man enough not to judge her . . . don’t let me down.

At the gate she closed her eyes dramatically and her lips dropped loose, as if the hand of a kindly God would surely caress her—from the trees, the wind, anywhere. Then she saw our rose bush. She ran toward it and buried her face in the petals. “Oh,” she squealed. “Red red roses! Aren’t they just love-ly?” Her voice too, unlike any Sim mons voice I’d ever heard, crackled with inflections of excitement, affectation, romance, discovery. Dad smiled and cupped her elbow in his hand, guiding her toward the house. I sensed that her joy not only brought him pleasure but refortified his hope that he could prove his brothers and sisters wrong . . . that the face of their worldliness and higher education (which he much admired) would not, in this instance, prove superior to his dogged faith. But I was afraid, for he was again believing what he wanted and needed to believe. It was so like him . . . stubborn, gracious, believing .. . to act upon the state psychiatrist’s faint admission that Lois might recover stability in her childhood environment. And no more than typical that he would discount the voices of his brothers’ and sisters’ misgivings.

“But Carl,” she protested, her fingers tripping over the roses, “how on earth do they get water?” I couldn’t hear Dad’s reply but saw him point toward the ditch. Almost shouting, she trilled: “Why that’s wonderful! Can you imagine that? From a harmless little old ditch! Why I thought they’d at least need a river!” They had almost reached the first tree when Mother called them back to help with the packages.

She always assumed the world owed her a living. Her motto was: Let everybody else do the world’s work and abide by the stuffy standards of decency—I’m Lois, I was born to have fun. . . . We know her all right —only too well. Back bone enough to recover? Just how much backbone did she show when she found out she was pregnant?

As they walked up the path under the trees, Aunt Lois looked all around her, as if in wonderland—first to the East Mountains and to big Baldy Mountain, and down the ridge to the cliffy gorge, Joe’s Gap; then to the range of the West Mountains, sloping off to the Pescadero foothills, running off to the pasture lands where her father’s cattle had once grazed; then into the thick-limbed poplars edging the village roads and house lots and down finally into the earth-stiffened path leading to the house of her brother, who alone among the twelve had chosen to stay in Utah and manage the family farm. I wondered what scenes passed through her mind as her eyes skirted over the unchanged landscapes of her childhood in the valley where she, the twenty-fourth and final child of her polygamous father, was born.

Suddenly about halfway up the path, she dropped the dress box she was carrying as if it deserved no existence in the scheme of her new life. “Oh,” she squealed and threw her arms around Dad’s neck, kissed him, and began to cry. Her face broke into an expression of overjoy. Emotion, normally not detectable in Dad’s expressions, worked up into his throat. But he gently broke her away, his hands firmly pressing back her thin, rounded shoulders. Right then even in its cut of resolution, his face reflected a shade of panic, as if he suspected reality creeping up on him, like the first movements of an avalanche of terror.

Dear-sentimental-fool-of-a-brother-whom-I-love-beyond-all-humans-on-the face-of-this-sorry-earth: Listen, Carl, it will never work. And it isn’t a question of insanity. Because actually, there isn’t a sane person in the whole family—except me. And Lois isn’t the craziest by a long shot—you are! Every time I think about your damn big-heartedness I get sick. Why? Because you’re the only person I care to remember from the “good old days” of our childhoods. And the memory makes me bitter because you remind me of the many times I played you for a fool and how little I have justified your persistent faith in me. . . . Did you ever stop to think that nine-tenths of the mischief caused in this mess of a world emanates from people who “try to do good”?

When I opened the door for them, Aunt Lois’s glance reduced me to a footnote in the family catalog. “No!” she exclaimed. “This can’t be my little curly top!” She leaned over the sharp edge of the dress box and ran her hand through my thick hair and kissed me wetly on my lips. “MMMM,” she said. “A big college man already.” She stepped back, looked me over. “And so hand-some!”

Inside the house she dropped the dress box on the floor and struck a cheesecake pose, graced with slender, shapely legs, a thin waist, and too-thin arms. Her face, close up, retained the animation of youth but not the coloring. “Thereyou go,” she trilled. “I guess I’m still a million dollar baby!” But her laughter faltered and by the time she added, “Aren’t I?” her countenance was straining for assurances. Dad put his arm around her and said, “Sure, Lois, you’re as .. . beautiful … ” He detested that word, not only because it contradicted his Puritan values but it specifically symbolized the sort of vanity which had accompanied Lois’s downfall. “.. . Uh, nice-looking as ever, Lois.” Then, as if addressing a jury of unseen opposition: “You’re just as good as anybody else.”

First that criminal . . . then, well, marriage was all right for ordinary folks, fools like us, but not for Lois Simmons . . . the gay and happy life . . . no regard for our feelings . . . then the baby . . . then the strychnine . . .

But beautiful was exactly the word she needed. “Am I beautiful?” she asked. “Really?” Her eyes believed, then dimmed with doubt. Quickly, Dad led her to the Victrola. While cranking the handle, he pointed to the record already on the turntable. His hand trembled. “I’ll bet you remember this, don’t you Lois?” he said. She read the label, and an indulgent smile worked slowly over her face. Dad’s eyes glistened, and it was plain that “Turkey in the Straw” contained some meaning that Mother and I were shut out from. The violin began, scratching and wailing, tunneling from the past, and Dad offered his hand and swung her into a quick two-step. His agility surprised me, not so much the bounce of his stocky body, but the vigor of his spirit. She squealed happily but, badly out of step, soon faltered, then quit in confusion. “Oh, Carl,” she pouted, wringing her hands helplessly. “Not that old pioneer stuff!” Her brother’s eyes flashed a hurt, but he rallied a smile and again picked up the threads of their game. I’d never seen him act up so. He bowed and said, “As my lady wishes!” She giggled, arched her brow, and offered him a limp hand, which he slightly kissed with the aplomb of a half-baked count. “Anoth-ah time, pah-haps,” she said. She wiggled away, like a movie queen, turned and laughed, her whole face breaking pixie-like into squeezed-up lines of wrinkle. Her tribute to wantonness—even in sport—brought flickers of embarrassment into Dad’s eyes.

Carl, do you honestly think she will ever fit into a Relief Society ladies’ quilting party? Or a Sunday School class? And what else is there for her to do back home? You’ve got to think of the time she’ll have on her hands. You mentioned her helping you at the elevator or getting a job in one of the stores in Rockland. Lois, handling money? Have you forgotten her escapades with the criminal . . . ?

Dear Diary: When everything is all right again and Ralph is out from jail, I will get away from them. All of them, and run away with him and help him rob stores or do anything else he wants me to do.

I didn’t know to what degree Dad expected me to indulge such goings on. Embarrassed, I picked up the packages and took them into the spare bedroom not knowing when or how my Great Role should begin. Above the splat and crackle of deer meat that Mother had begun to fry, I could hear Dad and Aunt Lois laughing, on her terms, like children playing as they pleased in a candy house they themselves had built. I remembered the little signs I had seen in Dad’s eyes, and I thought: How is Dad going to succeed where his own father and mother had failed?

Dear Diary: Father was a mean old man. He couldn’t stand to see anyone having a good time, or laughing. I was playing in the yard with two or three other kids and we were laughing and he came over very gruff and threw my doll over the fence, and said: “What’s all the cackling about? Go do something useful for a change, ” and made me go pull up pig weeds the rest of the day.

And about Mother, Diary, well, for all the trouble I caused her, she never once accused me of hurting her. Instead she’d always say, “Oh, Lois, if you only knew how you were hurting your father. “And he was dead, mind you, died even before we moved to Logan. (Mother said we moved so we could all “get a good education, ” but I think she mostly wanted to get away from the first family.) She always talked as if he were still living, and when I’d ask her how could I be hurting him when he was dead she’d say, “He isn’t really dead, Loiey, he’s watching you every minute of every day and he feels terrible about the things you say and the naughty things you do.” She had me believing that stuff too. Like to have scared me half to death when it’d thunder and storm. I’d get spooky feelings, like he was really right close to me, like I could almost see his beard and his cane and his big wrinkled hands — watching me and groaning about how bad a girl I was, and never following the way of righteousness like he taught, and cussing the whole family for moving from the family farm to the “evil” city. I’d be so scared, Diary, I’d promise myself in the pillow I’d be good the next day and all the rest of the days if only the thunder and lightning would just go away and take him out of my mind. But the next day I knew he was really dead, so I’d go on doing and saying the same ole things over again.

Since Dad had to attend a bishopric meeting that first night, he asked me to take Aunt Lois to Aunt Cally’s. As the last survivor of the underground days of polygamy, as Grandma Simmon’s youngest sister, and as the woman who danced the last quadrille with Grandpa the night he suffered his last stroke and died, Aunt Cally had earned the highest respect. Unspoken protocol demanded that she would be the first among the few relatives remaining in the village whom Lois must visit.

Aunt Lois minced over the crude cross-lots trail as nervously as a killdeer. When we reached the lane she stopped suddenly and looked directly into my face, reflecting the mischief of a little girl with some grand scheme up her sleeve.

“Listen, we don’t want to go see old Aunt Snickly-Fritz,” she said. As she spoke, she was already flying.

“You don’t think I can run? Why, I used to win all the girls’ races.” She sped away, throwing her head back recklessly. “See?” she yelled back over her shoulder, “I guess I can still ru . . . ” She stumbled and instantly reached out for the fence wire. By some miracle of dexterity, she did not quite fall.

“Are you hurt, Aunt Lois?” I said, jogging up.

“Oh, just a scratchy bit,” she laughed. One of her fingers showed consecutive pinheads of blood, and when I looked down she impulsively smeared the blood across my face and laughed. “There you go!” she shrieked. “I’ve got my mark on you now!” Then she plopped the bleeding finger into her mouth and laughed, and in the dark I did not know how bad the finger was so we walked back home; she, talking periodically over the top of her finger, which she kept between her teeth, biting down hard when she laughed.

As the days went by, I realized that what Dad had told me about the predominance of my role was true, especially since he and Mother often worked far into the night at the grain elevator in Rockland. Sometimes she went with them. She typed extremely fast, and Dad said he knew he could get her a job with one of the Rockland business men after the grain season. But she tired quickly, couldn’t work more than two hours, and spent the larger portion of the days home with me. I timed my fence fixing and other miscellaneous chores so I could be with her most of the time. Usually, she was passive, childlike, pleasant. She liked our walks across the foothills, went into raptures over wild flowers, asking simple questions about the life-death cycle of plants. But I could not exactly determine whether her questions and her seeming acceptance of my answers were genuine or center stage. And her moods, switching impulsively from hilarity to moroseness, often seemed edged with cunning.

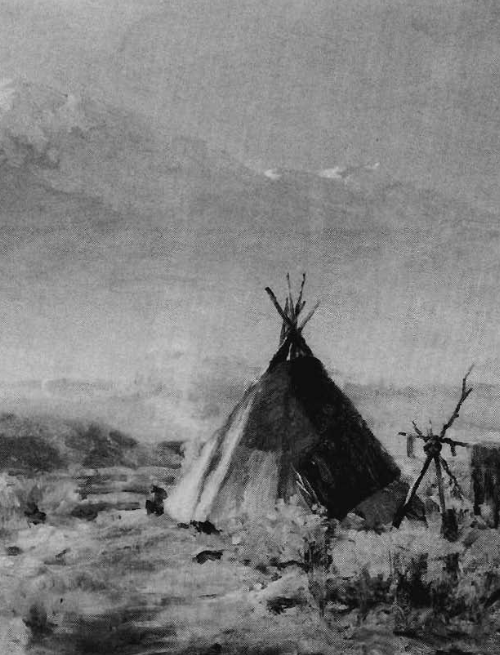

She was most content when we would prepare a lunch, drive the pickup to the foothills, walk through the mountains, and end up our excursion sitting on Cemetery Rock in the Joe’s Gap gorge. There we listened passively while the wind hummed through the chokecherry bushes and the pines swayed out from the cliffs. I was surprised to hear her quoting sizable passages of poetry—principally from the English Romantics—Byron apparently her favorite. She told me reading poetry was all she ever did in high school.

But her night moods were entirely different. The door between our bedrooms ordinarily lay shut, but Lois, the first night, had announced, “We’ll just leave it open a teeny-weeny bit, won’t we?” then added emphatically, “So we can breathe.” But the second night when I absent-mindedly closed it, she leaped out of bed, threw the door wide open, her eyes sparkling with fury as she shouted: “Will you please Judas Priest Almighty leave this door open!” Boom! The door struck the wall . . . then silence . . . then a pillow thudded against the open door. My laughter brought her head bobbing around the door frame and a shoe sailed over my head. In her fury there seemed an element of enjoyment, of luxury. “You coyote bastard,” she said, her voice trembling. “You screwy southpaw,” I said, laughing. In that way we bantered, like children, until finally her repartee melted into compulsive giggling. Sometimes her squeals spilled into her pillow as the paroxysm made her unable to speak. Often she would fall asleep between spasms of laughter. It was as if all the carbonated laughter and nonsense of childhood had been bottled up and was only now exploding. But this belated spilling from the general grimness of her past was only the froth of her personality. As I learned a few evenings later:

I woke, sensing motion from her room. I listened closely. A word, a phrase, half-whispered, blended into the light thump and patter of rapidly moving feet. She sang, softly:

I met a mill-ion dollar ba-by—

In a five and ten-cent store . . .

She answered herself in whispered, dry, sensual, unsung, throaty tones: “And he said, ‘Baby, do you want any more?’ and I told ‘im, ‘Why sure, lover, sure I want more.’ ”

You made—me love you—

I didn’ t wanna do it . . . I didn’t wanna do it . . .

Breathing heavily and, “Oh yes, I did. I sure guess I did!”

I got up, went to the doorway. Unperturbed, she blew a kiss my way and immediately drew me into the mesmeric atmosphere which had spread itself throughout the room. It was not a matter of pretending—the room had become a ballroom, gigantic, palm leafed, deepened in echoes of soft trumpet, muted in shadows, and the spell was such that I could imagine myself bedecked in tuxedo and silk hat, she in freshest taffeta. And the dream-world magic of her creation seemed to hold all that life might have been for her, if, as the family so often said, “things had been a little different.”

“Don’t you dare tell me to go to bed,” she whispered thickly, spinning on her toes, tossing her arms high above her head, making her wrists go limp. “Watch this . . . this is the way we danced.” The ghost orchestra commenced a waltz, while she dreamed her head back and danced . . . upon marble floors beneath crystalline chandeliers—

Ever in dreams . . . with you . . . I’ll sway-ay . . .

To the waltz . . . you saved . . . for me-a . . .

Turn turn te-ti tu . . .

She stumbled upon the bed, sighed sensuously, cupped her chin under her hand, looked through me, frowned a bit.

Diary: If they put me in a cell with him that would be hunky-dory with me. Because just give us a floor and we will make the music . . .

Her eyes narrowed and as I gradually came into their focus, the ballroom slipped away and the tones of trumpet faded. I turned to leave.

“Wait,” she said. “I want to tell you straight to your face … “

“What?” I said, not really asking anything . . . sensing a battle I didn’t want to fight, or even know about.

“The trouble with you,” she continued. “You’re like the rest of them.” She sat up, intense. Her voice leveled and was like cold water. You poor damn chicken, living in these Lord shielded mountains. You don’t know straight up.”

I didn’t say anything. I both knew (the nerve of conscience?) and didn’t know (the bliss of personal myth) what she meant. But I felt instinctively it was right that she should unleash the furies tormenting her, and right—perhaps for my sake as well as hers—that I should listen.

She motioned me to sit beside her on the bed, and I had to obey. For in that moment she changed from the ballroom belle into my aunt, privileged, like all aunts, to admonish. She was not “poor Aunt Lois” now either, needing therapy; no, a woman now, and I a boy.

She took my hand, faced me squarely, and demanded: “Look at me. Get serious. Do you think I’m a million dollar baby? Or not?”

I squirmed. “Well . . . I . . . ,” and begged somebody for inspiration. “What did Ralph think?”

She took the name in stride, as if it were perfectly natural that I should know about Ralph Turner. But I sensed that the river of her intention—whatever it was—had taken another course.

“Ah, Ralph.” Her voice stroked the name, and a small smile pushed her lips down. Her eyes glowed and the smile tripped back and forth. A big curtain rolled back and there stood this woman, small, defiant, afraid, in the center of the stage, alone.

“I can tell you one thing: I meant more than a million to him, and I cost him more than money. Isn’t it crazy? He was the only guy I ever wanted to give everything to. Everything I had. And for nothing.” Her voice stumbled. “Absolutely nothing.” The irony of the here and now must have struck her mind. She snickered, her smile fixed and grim. But her tongue idly ticked into another song and took her away again, to center stage.

We were sitting on top—

On top o’ the wur-uld . .

Her eyes snapped. “And we’ll get back up there too,” she said. “Because we don’t need a house, a car, a job —nothing. Just to be together. That’s all.” Suddenly, she threw my hand back. “I know, damn you,” she said. “You don’t have to say it, you think everything’s over. You think I’m only your rutty old aunt and he’s a withered up old jailbird and he won’t ever get out and you think I’m crazy waiting for him when I could have any man I wanted. But what do you understand about our kind of love? Nothing, that’s what. Absolutely nothing! Oh they’ll tell you all right he’s the scum of the earth, a common crook —oh they got it all figured out real sweet what love is, they know all about it. Love —sweet, sweety pie love: ‘I’ll love you if you’ll be the same church as me and think the same thoughts as me, but when you don’t, oh I’ll still live with you all right but I won’t love you any more, I’ll just feel sorry for you! That’s the way they tell you —that’s all the more they know about love. Well, let me tell you something, Chicken Little, Ralph and me, we loved real big and real strong, rules or no, and we knew better loving than these holy Church lovers, and it wasn’t dirty and cheap either like they say it was. Because they’re dirty and cheap, that’s what I say, Chicken Little, and don’t think I don’t know — I’ve had Saints in bed too, and sure, sure they get real excited, like eating a raw hamburger and treat you about like that too.”

One night the ward missionaries were visiting and Lois strutted out from the bathroom with only a towel around her waist, smoking a cigarette. And when mother ordered her from the room she flew into a rage — right in front of every one—and accused one of those visiting elders of having attacked her one night after a high school party. This incident was only typical of poor mothers heartache and suffering throughout Lois’ adolescence . . .

I made as if to go. “I don’t care,” I said. “Don’t talk like that . . . I don’t care . . .”

. . . When she was small father used to spank her for saying things against the Church, but poor mother, about all she could do was cry her heart out and plead with her not to revile the servants of the Lord . . .

She tensed, as delighted as a fisherman making a strike. “Ha,” she said. “Hurts your holy white ears doesn’t it, Green Willow? Well, listen real close and you might learn something or two for a change—they do it fast too, like they just can’t wait to get it over with so they won’t be late for priesthood meeting. Now—how do you like that!”

“Shut up . . . please . . . it’s none of my business.”

“Oh, you just think it isn’t,” she said, her eyes glistening with pleasure. “And another thing, the Saints got you believing a whole bunch of one-woman-to-one-man-crap, that making love with others breaks the whole thing up. But let me tell you, Green Willow, Ralph made other women and I had other men, we both knew that, but you think we cared? You think that stopped us from loving each other? It’s who you love most that counts and how you going to know you’re the best, how you going to know you deserve to be loved if you don’t have any competition? I tell you we weren’t scared ’cause our love was a great big love, a bigger love than . . .”

“So big it broke up,” I muttered. “Just like the family and the Saints said it would. That’s why the rules are . . .”

“No!” she screamed. And I thought she would strike me. Instead, her hands clenched a corner of a sheet, as if ready to tear it.

“No . . . stronger! Dammit! Stronger than anybody else’s. That’s what you great white-eared Saints don’t understand. You’re all in love with your Lord damn lies and never understand that real life goes deep and is tough and wonderful. I’m his million dollar baby now and forever. But you righteous bastards got to put us away and spit on us ’cause you’re afraid. Sure, we had an accident, that’s the tough part, but we dared anyhow, we dared to . . .”

Whether she’s our sister or not the fact remains she tried to take the life of an unborn child, and perhaps her own life as well, for all we know . . . is this the kind of person you want in your home?

“Sure, that’s when you Saints step in ’cause we’re weak then, helpless—you got too damn many laws and too damn many places to put people in. You wait around jealous, wishing you had guts enough to have some of our strength. Then we have an accident, a little bad luck, then you leap on us like a pack of jackals, trying to chew us to pieces. No, you don’t want us around to remind you of your sweet little dull routines . . . so you can cluck your tongues and say ‘See: Told you so!’ Sure, it’s easy to keep out of trouble—get married, eat, sleep and have sex once a month, twice if you feel real naughty. Ha!—that’s living? No, you can’t stand anybody who lives outside the nicety, nice little rules—you’ve got to huddle together like a bunch of nanny goats in a storm and congratulate each other how nice and holy and sweet and righteous you all are.”

“Why tell me?” I said. “You expect me to go out and preach your gospel? You think I’m a living image rulebook on correct courtship and marriage? I don’t know about these things and don’t care. Why don’t you leave me alone?”

She dismissed my protest with a wave of her hand. “Oh, you’re a green little willow,” she said. “I’d just as well talk to a damn post. Why, I’ll bet you never made a woman in your entire life. You’d like to though. Only you can’t. You’re protected by these holy mountains and these Lord God people who’re nine-tenths dead since the day was born. Think you can escape? Ha! Just try it. Oh you’ll get out of this part of the country all right —that’s not what I mean. Sure, they’ll send you on a mission, but by that time they’ve stolen your mind so you can’t learn anything except what they’ve told you to—and you’re so far gone you think great poetry consists of those sticky little verses in the Relief Society magazine about seagulls. Oh no, you’ll never be put away, just dopes like me. You’ll come back, marry a chaste little Mormon girl in the temple—just like you’ve been told to do—make love in your holy underwear, and commence having babies once every year or so.”

I felt afraid. Not of her, but of what she was saying. I felt cold, wanting to clutch tightly at the pontifical coat of orthodox religion, to hold the warmth in, against the bitter winter’s wind of my aunt’s malcontent.

“Just you hold the phone a minute!” I said. “I might be your green little willow, but maybe I can see things you can’t. All right, so maybe the Church rules don’t fit every particular personality, every single condition in life. But suppose the Church made exceptions. Suppose it tolerated your kind of medicine. Why, the whole structure would collapse. Aunt Lois, can you imagine the confusion, the terrible panic of human beings scrambling like animals for the shelter of a belief they couldn’t find? No—civilization has got to maintain simple lines of authority to feed hope into people—simple rights and wrongs, a simple system of reward and punishment, simple superstitions and fears—Oh, have it your way then! Not only simple but simple minded. Doesn’t matter. The people have to have guidance and hope, or else they’re lost . . .”

“Good!” she shouted, her eyes sparkling. “Damn good. I hope I live to see the day! I hope every damn one of the smug bastards gets as lost as they’ve made me be. Church people!—they’re the Lion, they rule the whole damn forest, and the dreamers are the lamb. Why in hell’s name can’t they lie down together? The lamb’s willing, I can tell you that!”

“Is it?” I said. “I don’t think so. Because the Saints have had to be dreamers too, early in their history. But they organized and built an empire. That’s why they’re the Lion now, and indestructible. And if the Lion ignored the lambs, they’d bunch up and destroy him with their own dreams. Then the lambs would organize and protect their own, feeding in the beginning upon the Lion’s corpse.”

She smiled, apparently pleased with the flow of words. Her eyes twinkled. “Shut up,” she said. “You talk too much. And where’d you get all those fancy words?”

I smiled back as our seriousness broke for a moment, and we laughed softly, together. “Well, Aunt Lois,” I said, “you’re not the only one who has read a few books and developed a few original thoughts.”

She propped the pillow against the bedstead and gathered her knees under her chin. Weariness spread across her features, accompanied by a certain atmosphere of contentment. She sighed, stretched, pulled her lips into a grotesque twist that started as a yawn and ended as a pout.

“Green Willow,” she said, “isn’t it the funnest fun being lazy? Like walking up to Pine Canyon and not having anybody along—or building a campfire under Cemetery Rock with those cliffs and all, and hawks floating around in the sky as free and pretty as you please, and the wind whooshing down slow then fast so it’s sort of cold but not too much, and yelling across the gorge and getting a couple of echoes back from the cliffs. Just us, and whistling or singing or climbing a tree and nobody to point a finger at us and say ‘No!’ Let’s go there tomorrow . . . and take a lunch. Okay, Green Willow?”

Dear Diary: I could count the stars easier than I could count the number of no’s in my life, not only all the things they wouldn’t let me do but all the things we never had: No money, no space to live in, no fun, no freedom, no friends.

Her eyes went very far away again. “It was peaceful like that sometimes in the mountains before we moved to Logan. It was a mess too in that little old log house, but sometimes it would be calm and you could dream. I remember that dirt roof, how the rain leaked through on terrible nights. And the trap door that used to go down into the tunnel where Mother told us Father used to hide when the marshals would come after him for having two wives. I never saw the real tunnel, it was just a potato cellar by the time I was born. But why I remember the dirt roof is when it rained I’d get scared and cry and he—Daddy—would come over to my bed and pick me up, and some times it’d thunder and lightning like mad, and he was so big, you just can’t imagine how big he was, such an awful big and strong man, even old like he was, and his chest broad and thick and warm to snuggle against, and I’d sniff against his shoulder trying to keep on crying so he wouldn’t put me down because I knew nothing could ever hurt if he’d just keep holding me. I felt strong and brave next to the thump thump beat of his big heart and because I knew he’d fought about as many Indians as he’d baptized, and rode the Pony Express and been shot at by marshals and a hundred other adventures. He’d walk back and forth with me in his arms and hum ‘Turkey in the Straw’ right slow, or ‘Rock of Ages,’ and say through his beard, muffled in his beard, his voice very quiet, muffled through his beard . . .”

She stifled a whimper, managed to go on. “‘Loiey,’ he’d say, ‘Loiey, my little Queen, whatever is going to become of you when I die?'”

She shoved her fingers into her mouth and bit down hard. She sobbed and her eyes filled.

“Go on,” she whispered huskily, getting back control. “Go on to bed; you got no right to make me talk all this junk. None of your damn business!”

She plunged into bed, face down, and jerked the covers over her head. Her hands clutched the pillow tightly. Underneath the blankets her feet kicked once, like a nerve.

Dear Diary: Daddy was holy all right, but sometimes he’d be ornery to every body and get away with it. Nobody’d dare cross him, and that’s when I liked him most—when he wasn’t so holy, he was a real shoot-em-up, in fact. Yes sir, he was a damn good hell’n bent shoot-em-up. Drank like a fish and got in fights at the dances. Licked everybody who said no to him and carried the prettiest girl off on horseback. His father was a big wheel in the Church—almost as high as the president—so he thought he could get away with anything and he did too. But he got his comeuppance one night when he rode his horse up the churchhouse steps and right into the dancehall . . . shot out the lights, just like in the movies. Scared the living hell out of everybody. That’s when he was kicked out of the Church and that scared the hell out of him—you bet your fanny he came crawling back. And like when he did anything, he went the whole way, he threw away his plug and his bottle and never touched tobacco or liquor the rest of his life. Whole hog or nothing — like the way he treated the bums that’d sometimes wander to our house, he’d either give them all the food we had in the house and put them up for the night, or he’d kick their fannies and yell at them all the way down the road, ‘For God’s sake go out and make a living and be respectable like everybody else!’ Anyhow, overnight he changed from the slickest dressed shoot-em-up cassanova to the raggedest preachingest Mormon that ever lived. Why, Mother used to say he preached sermons with his chore clothes on and you could hear him yelling three miles away.

But Diary, what’s funny is everybody else inherited the sermons, but I got left with all the shoot-em-up.

The days went on. But not the same. She had turned a corner and was frightened. She castigated me at every opportunity, furious that I should have glanced into the world of her private emotions and, by so glancing, remind her that hate and love are not easily divisible. She became cruel, petty, sulky; she complained about the food; she didn’t have enough room; the bed creaked. Why couldn’t she go to Rockland at nights alone; a hell of a way for a brother to treat his own sister, just like she was in jail; and there wasn’t even any coffee in the house. She played practical jokes, like putting sugar in the salt shakers, and screamed hilariously at the results. I met these juvenile plays for attention with as much tolerance as I could muster.

One evening she sauntered happily from her room into the living room, where I was reading. She had cheese-caked before, but not quite this boldly. She was wearing only a towel tied around her waist. She stood beside the couch, her chin thrust high and arrogantly.

“Well,” I said, looking up. “Mighty lovely. But don’t you think it’s a little conservative?”

She knocked the book from my hand. Her nostrils quivered and her eyes flashed fire. “Don’t you realize your Dad hasn’t bought me a new dress since I got here? Not one! Here I work my fingers to the bone, cooking and cleaning this Lord almighty house and what do I get for it? Not a red cent. You just stuff your bellies and never even say thanks. And what do you do? You lazy little cockroach, you just sit on your butt all day and read longhair books and won’t even help me. And don’t think I don’t know why you never help at the elevator—sure, you gotta stay home and spy on your loony aunt, tend her like she’s a baby. And they give you anything you want, too, like you’re a king or something, but what do / ever get? Two smelly old house dresses and a cheap Sunday dress, and only one pair of silk stockings. I’d just as leave be in jail. Can’t go anywhere or do anything but just work. Every livelong bastard day!”

I got up, shaking with anger. I wanted to hit her but remembered Dad’s entreaties for kindness and patience, his sympathetic portrayal of her life in the asylum. “How many dresses have your other brothers and sisters bought you?” I said, struggling for complete self-control. “Now forget it. Go get dressed. I’ll fix supper. You won’t have to do anything. I’ll even fix you a cup of coffee.” Unknown to her, I had at last persuaded Dad to bring home a pound of coffee — the first and last that ever “disgraced” our cupboards.

I walked into the kitchen, affecting unconcern. She stormed into the bedroom. “You haven’t got any blood!” she screamed. I forced myself to ignore her. A period of silence. Then her voice, inflected with sarcasm, teased from the bedroom.

“What’s the matter . . . you scared, Green Willow?”

“I just don’t believe in incest, that’s all,” I said. I tossed it off lightly, tried to whistle over the kitchen work.

“Oh of course not,” she said, sarcastically. “I know you’d think it wasn’t proper. But the real reason is it’s too damn dangerous for your timid damn soul . . .”

I purposely banged pans and closed cupboard doors. But her voice rose louder. “You’d say it was nasty and sinful, but you’re just afraid what people would say if they found out, or if they didn’t, what your phoney conscience with all the ghosts in it would say—oh, yes, you’re a big boy, but you still believe in ghosts don’t you?—Like the great big bad ghost of God, and the big bad ghost of my damn-hell father who I hate. You hear that, wet ears? I hate him!”

I tried hard to make my silence tell her I didn’t care. But I did care. I was trembling from head to foot. I wanted to choke her, literally choke that voice out of existence.

“I hate my old man and I’ve hated him every minute of my life. So put that in your pipe and smoke it!”

“You know all the answers, don’t you?” I said. But my words had the effect of gasoline on a fire.

“Oh you wanna make love to some juicy little Saint gal out in the alfalfa patch all right, but you ain’t got the guts to take a chance of knocking her up and having the Saints turn against you and having to make it alone in the world and find your own ways and rights and wrongs. You gotta borrow the rights and wrongs you been spoon-fed because you’re afraid to think anything by yourself, or think anything respectful of yourself.

“Oh you don’t need to pussyfoot your old Aunt Lois, you’re gutless and the reason is you’ve been hammered so much that it’s more righteous to take the easy way out—never do or think anything against the tried and true principles—them Lord damn principles that don’t make you a human being but nothing but a hell machine popping out morals a mile a minute. Oh I could tell you some pretty stories about the Saints. What’s the difference between them and me is just they never got caught. Oh they ain’t so holy . . . I could tell you some stories . . .”

Whenever Dad had asked me about her progress, I had given him hopeful answers. Even as she degenerated, I had come to believe, like him, in the miracle of her recovery. But now I would have to tell him.

“They got their mark on you . . . they got you buffaloed, you green little willow. I thought you had some imagination, but you don’t know any more than . . . than a castrated polecat. Oh, sure, you’ll be bishop some day, just you watch and see, and you’ll probably be the best and dumbest bishop this hell-damn town ever had. Just go right ahead, you green little fool!”

She began to cry. And my rage gave way altogether to a bitter kind of sorrow. I could not find the source of my feelings; but for the first time they seemed to reach beyond the actors in my own life, to encompass all of the human family—the Lois’s and Dad’s and me’s and everyone, bewildered and caught in webs of limitations spun of the materials of tragedy. And we—all of us—seemed blameless. And it seemed to me through the eternal dust of human intention—intention built mainly with fabrics of good will—surely Someone might have intervened, if Someone only cared enough.

I sat down and stared into the black window. The reflection startled me.

Her sobbing continued. “Don’t cry!” I shouted. Then silence settled deep, deeper than the silence of mountains. Suddenly a splendid light flashed through the semi-darkness of the room. The headlights from a car had shone against the wall, crawled the sectioned window pane, jack-knifed, merged into the ceiling, a blend of grace, spread easily over most of the ceiling, crawled down the side of the opposite wall then slid over my face. The window pane bars made a cross on my body. The car’s tires whined down the highway.

The car brought my mind from the mystery of pains and disunity in the universe of the human soul back to the necessity of fixed routines. The folks would soon be home, tired, hungry. I began slicing potatoes into a frying pan, thinking how ridiculous the eating of food is.

I hardly realized or cared that her crying had stopped, until a wail of song streamed from the bedroom, like a wisp of smoke, wandering its way through an exquisite, waning strength.

. . . and he’ll be big and strong . . .

the man I love . . .

Her tones fell sensuously, hopefully—as if she might yet spin a worthwhile reality from the invisible fibers of miracle. This quality of hope textured the singular and fatal stillness of the rooms. In my mind’s eye I pictured her lips curving and pale, trembling in search of coherency—the spirit of her hanging on—to some frail limb of hope—seeking decency, knowing the ineffable terms, rejecting all of them, except her own, whose meanings she couldn’t explain because they had no support, no framework in the judgment of her fellow humans.

She appeared in the doorway, her cheeks a dull-red from rouge, like a kewpie doll’s, and her face whitened with a thick layer of face powder. Her hair stretched loom-like above her ears, bobbed in back. Her eyebrows were penciled darkly with mascara. She wore her Sunday dress and high-heeled shoes. Her eyes gleamed unreal, twicking a pretention of merry wickedness . . . a serious mischief which fashioned for herself a queenship with subjects unnumbered and unknown.

I decided to do my best to make something grand of this scene, for it would be the last one. She’d have to go back to the asylum. I knew I’d have to tell.

“Here,” she said, striding toward me. “Let a good-for-nothing kitchen slave show you how to slice potatoes.” She grabbed the knife and recklessly spliced a potato in half. “This is all I’m good for.” Her face cracked into a wreck and she wept, without control.

Suddenly, and with a gasp of frustration, she lowered her arm and lunged. The blade sliced thinly over my open palm, but I caught her wrist before the point reached my groin. Helplessness came into her eyes as the knife dropped to the floor. Then she looked at the small smear of blood on my hand and raised it to her lips.

“Are you going to tell?” she whispered. I sensed she knew the Great Game was finished now, and was glad.

“Yes,” I said. “But understand, I don’t blame you. . . . I feel different about things . . . you don’t know . . .”

“Thinking’s no good—no good at all,” she said. “Come on, I want to play the piano. There’s a song-story I dreamed up in the hospital. And it’s just for you. All the lights out now, but the lamp.”

From the corner of the living room, I watched her seat herself fastidiously at the piano, as if the knife incident had never happened. She made a quaint picture of light and soft shadow, as lightly, tenderly she stroked the keys of the treble cleff, playing indiscriminate rolls. Her fingers coiled like stiff ropes above the keys as her hands jack knifed beneath her wrists. This was her right hand —tender, controlled, passionate, sympathetic, purely prospecting for rhythms, meanings, coherency. The probing was honest—bound to find something. There—the threat of a melody, almost like chimes. Suddenly her left hand struck like a cobra at the bass cleff, creating dissonant chords, resembling thunder. The pastoral-like melody fled, like a shadow in a burst of lightning. The chords rumbled violently, sound crowding upon sound, like animals stampeding into a wall. Then the left hand fell away and plunged limp into her lap. Silence —she looked at me. Her brow arched and out of the shadows came her voice:

Red sails in the sun-set . . .

Way out on the sea . . .

Oh carry my loved one

Home safely to me . . .

“This,” she said, racing her right hand fingers over the keyboard, “this is roses—red roses; and they’re growing beside a huge, huge river. And this,” her left hand again struck—”is the roaring, roaring river! And the roses … ” again playing only the right hand —”grow right beside this river, very brave and beautiful little things, not hurting a living soul. But the river” . . . Thump! Crash! Thump! . . . “It just keeps crashing up over the red-red roses, and every time it washes back it leaves the roses weaker and weaker until pretty soon they’ll have to give up. What else can they do? Their bushes are so small, you know, and they’ll be washed away and die. Where? Oh let me tell you where . . . let one who really knows tell you where:”

Down th e rive r of gold-en dream . . .

Drifting along , singing a song . . . of love . . .

She moaned and her head dropped over the keys. But only for an instant. Returning sweetly to her parable, she said, “But this river isn’t like the river of golden dreams. This is a helluva bastard river—you know? It don’t have good feelings and it don’t have beautiful dreams; and it don’t care about red-red roses, even if they’re just minding their own damn business and wanting to be free and beautiful in the sunshine . . .”

The right hand continued to dance, as softly as if a sparrow were running up and down the keys.

She smiled and laughed shortly. “And to think,” she said, “to think I tried to kill you. That’s darn near funny.”

“Maybe it wasn’t exactly me you wanted to kill,” I mumbled. She laughed scathingly. “Page 107, Introductory Psychology! Think you’re awful smart, don’t you. All that big time analysis stuff. What do you know about life? And what do those guys who write the big books know about it either? They just read—they don’t really live. But please—don’t interrupt a lady. I’m telling you a song-story. Maybe it’s too hard for you to understand, since you can’t track it down in a book. Well, I’ll start all over again. You see, the left hand music is a big flood river and the right hand is flowers—red-red roses, remember?—growing on the bank of the river. And the thundery old big river washes over the red-red roses whenever he feels like it, and he’s so mean it’s awful hard for the red-red roses to keep alive . . . they get all wet and dirty and chokey. See what I mean?”

Her left hand hit the bass keys with such force the room seemed to rock in a vertigo of sound. “Now maybe they’ll get swept away by the river.” Her voice was pitched high now — sonorous, majestic, and above the thunder. Louder . . . louder. “Maybe he’ll just pull ’em up by the roots and throw ’em away on the shore, all wet and soggy, and . . . dead! Oh, he’s an ornery old bastard. He don’t have no pity, not for anybody!”

She stopped playing, but her foot remained on the fortissimo pedal, causing the bass sounds to cascade with echo. Clearly a phase of the concert had ended. The twangy metal echoes died slowly, the room grew still, and she looked down into her hands, lying limp, palms upward, on her thighs. Then slowly, the right hand rose again, circled high, arched above the keys, then again touched them. As she played—only the right hand—she eyed me narrowly and spoke, as to a child: “Now pretend maybe the red-red roses—maybe sometime just one of them, just one measly little old flower —wild and beautiful and tough — will be so hell-damn almighty stubborn, so full of the Judas Priest Devil that the old man river can’t carry it away, and he’ll have to leave it alone cause it’ll be just twice as stubborn as he is. Oh, I don’t know if it’ll ever happen. And what do I care anyhow? But I’d sure hell-damn like to see it!”

Her mood shifted, and she pried into another melody. “Anyhow,” she continued, “that’s why you can’t hear the right hand very well — but it’s prettier, dontcha think?” She cocked her ear and her smile cued the right hand —into a dainty pirouette up and down the scale. “Just think! If I didn’t play the right hand at all there wouldn’t be any melody—just nonsense and thunder. So even if you can’t hardly hear it, I guess it’s worth playing after all, isn’t it?” She smiled and added, flatly, “Or is it?”

“Why not just plant the roses farther inland?” I murmured.

She laughed. “Ha! That’s all the sense you got! Whoever heard of a rose living without water?”

“You could move them a little ways back,” I said. “Far enough so the flood wouldn’t reach them, anyhow.”

“Oh, no,” she said crisply. “You don’t understand. The river follows you wherever you go. You’d die if you did that . . . for sure. I mean, you gotta live, haven’t you? So you better not be straying off; no, you better be staying close to it so you can at least fatten up before it kills you. It usually takes its good old time, you know, because it likes to tease and torment; but if you got away you’d die—die in a minute. No, you got to stay close—and fight.” She smiled again, pixie like. “The red-red roses, I mean.”

I felt time running out. I motioned her to the couch. She sat down beside me.

I put my arm around her as she leaned her head against my neck and shoulder. With my other hand, the one with the dried blood on it, I held both of her hands. They lay small and white and passive in mine, seemed anxious to be held.

“Aunt Lois, don’t think you are the only one with big bad rivers. They are not just one thing, or one person, or one group of persons. Grandpa had his rivers too,—you, for instance. And maybe he was wise enough to foresee that the Church would be your big bad river, after all.”

“Maybe that isn’t what I mean,” she said. “You don’t know.” She sighed, affectionately. “Anyhow, don’t read me that damn psychology book. I’m tired.” Then she pressed her face firmly against my neck and spoke into my flesh: “When they get home just tell them to take me back, the game’s all over. Don’t go into this other stuff. Your Dad wouldn’t ever understand. Nobody would. Anyhow, I’m too tired for a lot of words and fuss and bother. And someday maybe you’ll understand our little secrets . . . someday . . . but not now . . . you don’t know anything, yet.”

We didn’t speak again. . . . Once she opened my hand and kissed the palm.

In a few minutes car lights flashed in the window. Our eyes followed the slow march of the foursquared image, climbing the side of the wall opposite us, up the ceiling, then down again into our faces. We heard the sound of the car door, slamming shut, penetrating the vacuum of the night. She sat up, her eyes alert, darting wide with preparation for the next few moments’ reality. She glanced nervously at me, smoothing her dress. Her lips tightened, and she wet them with her tongue. Then—quickly, for she had forgotten—she dabbed a doilie upon the spot where the blood from my hand still marked her lips.

Dad’s voice sounded from the porch. “A busy night!” he said, opening the door. “Sure seems good to get back home!”

***

(1961)

The hospital stood tall and dominant at the south end of Center Street. It was a convenient place to turn around. In the seat beside me she stared blankly ahead; her arms resting folded upon her mountainous stomach.

“Well, it’s goodbye to all of that,” I said, making the U-turn.

“Those was sure funny things you talked about in the drug store,” she said, her voice whining. “My goodness, I don’t remember all those silly things about me.”

(Try, a voice said: if you’re a writer, you’ll try —once more.) “But I didn’t tell you about the red-red roses, did I? A long time ago you told me a story about them. Do you remember?”

“Oh,” she whined. “Roses is all right, I guess. But flowers kind of bother my sinus. My health isn’t as good as it used to be, you know . . .”

As we drove past the “House of Happiness,” she shifted the blubbery mass of her body and with great effort stood on her knees, facing the “House” squarely. She cupped both hands over the half-opened car window, like a child watching a parade, not understanding.

“What are people like out there? —in the outside world?” she said.

“Like fools,” I said. “Always trying to do things they can’t do.”

She settled back into the car seat. “Well, I don’t know if I’ll like it after all,” she said. “Cynthia, she was awful sweet to me, you know. Nursie said I’m cured now . . . But you think it’ll be all right? Outside, I mean? The Lord blesses those that pays their tithing . . . and I pay, . . . every time.”

“Sure, Aunt Lois,” I said. “You’re just as good as anybody else.”

I pressed down on the accelerator. There was a bad stretch of road through the mountains. And Dad had promised Aunt Cally we’d be home early.

Before dark.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue