Articles/Essays – Volume 09, No. 1

Phrenology Among the Mormons

On 2 July 1842 the Nauvoo Wasp contained a letter from A. Crane, M.S., professor of phrenology, alluding to the “large number of persons in different places” who wished to know “the phrenological development of Joseph Smith’s head.” Having examined the Prophet and obtained his permission to publish the results, Crane gave his analysis under the usual phrenological categories. The Prophet rated high in Amativeness, Philoprogenitiveness, Approbativeness, and Self-esteem; in other words, he was “passionately fond of the company of the other sex,” exhibited “strong parental affection” and “ambition for distinction,” and possessed “highmindedness, independence, self-confidence, dignity (and) aspiration for greatness.” Besides being printed in the newspapers this chart was copied in the Prophet’s “history” with this comment: “I give the foregoing a place in my history for the gratification of the curious, and not for respect to Phrenology.”[1]

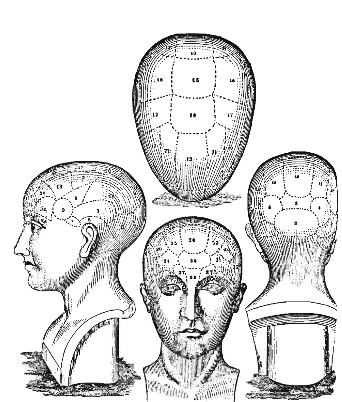

Phrenology was still a fairly new thing in America. The founders of phrenology in Europe, starting at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, were Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828) and J. G. Spurzheim. The movement had spread to the British Isles and during the 1820s and 1830s to the United States. The chief architect of the phrenological movement in the United States of the century were the “phrenological Fowlers”: Orson Fowler, Lorenzo Niles Fowler, their sister Charlotte, and a brother-in-law Samuel Wells. More than anyone else the Fowlers made phrenology a rage for several decades, so that “to be phrenologized was a perfectly routine, even fashionable thing to do. . . .”[2]

More than a few Mormons participated in the new enthusiasm at least to the extent of obtaining phrenographs. On 14 January 1840, Joseph Smith had obtained an examination at Philadelphia from Alfred Woodward, M.D., who filled out one chart on “measurements of the head” and one rating the Prophet’s faculties.[3] A comparison of the 1840 and 1842 readings reveals differences as well as similarities:

| Woodward | Crane | |

| Amativeness (love between the sexes) | 16 | 11 |

| Philoprogenitiveness (parental love) | 16 | 9 |

| Inhabitiveness (love of home) | 15 | 5 |

| Adhesiveness (friendship) | 15 | 8 |

| Combativeness (resistance, defense) | 12 | 10 |

| Mirthfulness (wit, fun) | 15 | 10 |

| Acquisitiveness (accumulation) | 12 | 9 |

| Imitation (copying) | 12 | 5 |

The Crane rating is on a scale of 12, whereas the Woodward rating is apparently on a scale of 20. The inconsistency between the two may help to explain the Prophet’s reserved attitude in 1842. Nevertheless, he was willing to submit to another examination in October, 1843. As recorded in his history, “Dr. Turner, a phrenologist came in. I gratified his curiosity for about an hour by allowing him to examine my head.”[4]

During these same years other Mormon leaders obtained phrenological ex aminations. The Nauvoo phrenologist Dr. Crane examined Willard Richards, Brigham Young, and others.[5] On June 24,1842 Wilford Woodruff recorded in his journal: “I called upon Mr. A. Crane M.D., professor of Phrenology, who ac companied me to my house and examined my head and the heads of my family and gave us a chart of each head.”[6] In the fall of 1843, when several Mormon apostles were in Boston, they called at the Fowler studio and obtained readings.[7] And it appears that Hyrum Smith was examined sometime before his death on 27 June 1844.[8]

In 1845 a young convert to Mormonism, James H. Monroe, was showing more than a little enthusiasm for phrenology. Employed as a school teacher for the children of Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and other prominent citizens, Monroe wrote in his diary on 25 April:

My time was spent, when not occupied with my school, in reading Fowler’s Phrenology, a very valuable work in my estimation, and containing much information of especial benefit to me in my present capacity, as it enables me to form a better opinion of the tastes, feelings, and powers of my little protiges [sic] and thereby suggests the proper mode of education, and tells me which faculties are necessary to be cultivated. I think I must make out a chart of their heads with a description of their character as shown by the development of their organs, and then concoct a plan for their education in accordance with those principles.[9]

He did just that, at least for some of his students. On 29 April he finished a chart of young Joseph’s head, “which admitted to be correct by his mother.” About the same time he observed that William W. Major, the artist, had well developed faculties of Constructiveness, Color, and the perceptive organs in general. In John Taylor he noticed large organs of Ideality, Mirth, Weight, and Combativeness. “This enables him to write poetry and combat[iveness] enables him to sit a horse well and makes him fearless in breaking colts, &c. I noticed the heads of individuals very much now, and hope I shall continue the practice as I expect to make it appli cable in all my business.” A few days later he was examining the heads of Oliver Huntington (large organs of Combativeness, Destructiveness, and Amativeness) and John Huntington (large organs of Firmness and Constructiveness). Monroe was determined to live in accordance with phrenological principles.” As he said, he was “fully satisfied of the truth of the science.”

James J. Strang, who became head of a splinter group after the death of Joseph Smith, showed some interest in phrenology. The first issue of Strang’s newspaper, The Northern Islander, printed his own phrenology in detail. And one of his best advertisers was the firm of Fowler and Wells, for whom he listed and described upwards of twenty titles in the final issue of the Islander.[10]

That interest in phrenology crossed the plains with the Mormons is indicated by a letter written in late 1852 by a Mrs. L. G. W. in Salt Lake City. “The Phrenological Journal,” she said, “has taught me how to govern and instruct my children, how to know a good person from a bad one, and is a never ending source of re flection, knowledge, and happiness. Large charts of heads hung up in a convenient place in a house for children to look at, soon interest them and by degrees they acquire a knowledge of the science.” She went on to say that the books she had purchased from the Fowler and Wells “Book room” were of “great value” in Utah. She regretted that she had not brought more of them.[11]

In 1869-70 the recently reorganized Female Relief Society of the Fifteenth Ward in Salt Lake City included reading and study as part of its program. One of the most popular sources of reading material, according to the minutes in the Church Archives, was the Phrenological Journal. Although this periodical had reading material on various topics, such as an article on the duty of parents to their daughters which the Relief Society ladies read, their willingness to draw from it indicates a general feeling of friendly interest in phrenology and associated subjects. And in the remoteness of Utah’s Dixie, Martha C. Cox, thirsty for reading matter, borrowed a few books from James McCarty. She added in her journal, “I also read Fowler’s Phrenological Journal which, with the N. Y. Tribune was always found on McCarty’s table poor as he was.”[12]

Not only were Mormon interested in phrenology; phrenologists were also interested in the Mormons. The Fowlers and others included the Mormon areas in their itinerary, something they would not have done had there been no clientele among the Saints. Furthermore, the periodicals published by the phrenologists included comments on the Mormons. These articles were not always friendly. In 1857, for example, a lengthy article based largely on John Hyde’s Mormonism—Its Leaders and Designs expressed the same distaste for Mormon practices as found among the American bourgeoisie in general. The editors did add the following comments:

The portrait of Joe Smith indicates an excellent constitution, good practical talent, but not great originality. The base of his brain was large, and his passions naturally strong. Self-Esteem and Firmness were large; hence he had a strong will and great pride and desire to be his own master, and to take the lead of others. Cautiousness was not large, but Secretiveness and Acquisitiveness were marked traits. His credulity was strong, but his Conscientiousness decidedly weak.

Brigham Young had a large head and a splendid intellect. His Constructiveness, joined with intellect, gives excellent power of combination and administrative capacity. He ap pears to have large Spirituality, which gives credulity, enthusiasm, and romantic spirit and possibly he half believes his own superstitious teachings. . . . His large body, abundant vitality and nervous power give him magnetism which he possesses in so high a degree.[13]

There is no unrestrained admiration here, obviously, but the phrenologists, who apparently had seen engravings of the Mormon leaders, did admit that they possessed some positive qualities.

One of the contact points between Utah and the Eastern phrenologists was the Salt Lake City firm of Ottinger and Savage, in whose bookstore the various publications of the Fowler-Wells publishing house were sold. Reciprocally, Ottinger and Savage provided some paintings and photographs that were admired by the phrenologists. In 1869 Samuel Wells published the phrenograph and biography of Ottinger.[14] Following one of several excursions to the West, during which he called upon his friends George Ottinger and Charles Savage, Wells wrote that he had “examined the heads of hundreds of the representative men and women of the Mormons.”[15]

In 1871 Wells received a photograph of Brigham Young from Charles Savage. Wells remembered that he had met Young and “taken his measure” years before and proceeded to comment on Brother Brigham’s phrenological characteristics. Some of the most interesting observations from this fairly lengthy article are as follows.

Though born with the spirit of a captain, he is not arrogant, over-dignified, or at all distant, but rather easy, familiar, and quite approachable. . . . He will be kindly to friends, family, and young, and indeed to all his household and people; but for every dollar ex pended in behalf of any person, he will exact its return with interest.

. . . He has large Ideality, Sublimity, Imitation, and Mirthfulness; and he is a natural orator, a wit, an actor, and he may be said to be a perfect mimic. . . . As to the number of his wives or children we know nothing except by hearsay, but we have every reason to believe that Brigham Young is today less sensual in his habits than many who profess to live lives of “single blessedness.”

In almost any position in life, such an organization—with such a temperament—would make itself felt, and would become a power within itself. . . . God will hold him accountable for the right use of a full measure of talents. .. . He may be a saint—he is probably a sinner—but he is neither a fool nor a madman.[16]

Although Wells carefully refrained from endorsing Mormonism or plural marriage, it is obvious that he admired Brigham Young.

Wells may have been influenced toward a positive evaluation of the Mormon leaders by Edward Tullidge, who contributed several articles to the Phrenological Journal. He was writing such articles at least as early as 1867. In a letter to Brig ham Young, Tullidge describes the visit in company with Apostle Orson Pratt to the Fowler studio in New York City on 13 May 1867:

The Office was quite in commotion at the presence of a Mormon Apostle, and as a privilege both the principal phrenologist and the proprietor, Mr. Wells, had to lay hands on brother Orson’s head, one after the other, not hearing each other, and then brother Pratt to their amusement and friendly feeling expressed a desire to do the same for them at some future time.[17]

Tullidge went on to mention Pratt’s prayers that the editors would “accept my articles in the exposition of God’s work and truth. . . .”

It was probably Tullidge who in 1871 supplied the periodical with an article evaluating the leaders of the Godbeite movement in Utah. Elias L. T. Harrison was described as having a forehead “massive with Causality, and Comparison very large.” Cautiousness and Conscientiousness were said to be the largest organs in the head of Henry W. Lawrence, “which is decidedly the head of the practical and enterprising man. . . .”[18] Although Tullidge had been excommunicated along with other followers of the New Movement, he remained friendly. As his later writings demonstrate, he retained more than a little admiration for Brigham Young and other leaders. Since he was in touch with the editors of the phrenological periodicals, he was for several years probably the main channel by which information about the Mormons was conveyed to these journals and their readers.[19]

A real burst of phrenological excitement occurred in Utah in the year 1872. In late January Professor McDonald of Scotland was giving lectures on the subject at the Tabernacle. At the lectures he drew “very large audiences” and in giving individual examinations he did a “rushing business.” Finishing his series in Salt Lake City, McDonald left for Provo.[20]

Just after McDonald’s departure, the city buzzed with excitement at the arrival of the greatest of them all, Orson S. Fowler. Besides lecturing on phrenology itself, Fowler gave lectures on such subjects as “Female Health and Beauty Re stored,” “Love, Courtship and Matrimony,” and “Manhood; its Strength, Impairment and Restoration.” This entire series was repeated once for a “ladies only” audience.

There was some skepticism expressed and some good-natured raillery directed at Fowler. It was a standard part of his lecture, it seems, to call for someone from the audience to be examined publicly. When the professor asked for two people in his opening Salt Lake City lecture, there were “loud calls” for James B. McKean, the militant anti-Mormon judge. McKean steadfastly refused. Bishop Edwin D. Woolley assented “good humoredly” and ascended the stand. Then the audience called for E. L. T. Harrison, editor and publisher of the anti-Mormon Salt Lake Tribune, who agreed from “a sense of public duty.” The two victims were seated facing the audience, “the bishop’s face wrinkled with smiles, and Mr. Harrison looking as serious as if the axillary revolution of the earth was on the point of being reversed.” Fowler analyzed both men, concluding with a dramatic comparison. As the Salt Lake Daily Herald described the scene:

With his left hand on the caput of the bishop and his right on that of Mr. H., he thus comparatively commented, beginning on the left and alternating: This character is centriputal, that centrifugal; this is a circle, that a triangle, this will obstinately keep in the rut of the old road, that hankers after cross roads and new cuts; this orthodox, that heretical; and so on, continuing the contrast in almost all of the prominent characteristics, and making the two gentlemen in every respect the antipodes of the two Dromios.[21]

The Salt Lake Tribune, Harrison’s newspaper, was not impressed with Fowler’s performance. It reported that the examinations “disgusted very many of the audience” and that “any new beginner could have done better.”[22]

Typical of the humorous ridicule to which Fowler and his phrenology was subjected was the story of the lady who asked him to examine her baby and tell what professions he was suited for. The professor felt that infant’s head and said, “Madam, I find the organ of benevolence enormously developed. It is as prominent as a pigeon’s egg. Train up the child to give alms to the poor. He will someday be President of the society for the prevention of indigence to the starving. Madam, my fee is ten dollars.” She paid the fee, took the child home, applied both thumbs to the organ of benevolence and “squeezed it until the depression would have held a walnut.” The child grew up and, as the story concluded, “for twelve years has supported his parents by stealing.”[23] Even the report of this story, however, was softened by the statement: “Professor Fowler’s reputation is so firmly established that poking such fun at him can’t hurt it.” In general, the reaction of the Deseret News and the Salt Lake Daily Herald was friendly, open-minded, and positive. And the reports seem agreed that attendance at the lectures was consistently large and enthusiastic.[24]

A large part of Fowler’s activity on such tours was in giving private examinations; in fact, the lectures served the purpose of “druming up” business. The newspaper advertisements reminded Utah readers that he was available for consultation by individuals or small groups at the Townsend House.

One of Fowler’s stated reasons for coming to Utah in 1872 was to find out whether the mental health and physical development of the children of polygamists were as high as those of monogamous families. When asked to state his conclusions, he showed a characteristic ability to avoid offending either his Mormon hosts or the larger American public: he hadn’t seen enough to draw final conclusions; the children of polygamists were not inferior; this should not be understood as taking a position either for or against polygamy.[25]

Fowler was interested to discover the Mormons’ organ of veneration to be highly developed. The Tribune responded as follows:

The Professor the other evening told the public that he found in the Mormon head the organ of veneration largely developed. Of course he has. Mormon theocracy and obedience to the Priesthood without asking any questions is founded upon this same organ of veneration. . . . We would sooner “bet” on the small venerative bump than on the large, for the bump No. 7 bring forth Books of Mormon and theocracies and perpetuates delusions.[26]

In late 1881, Orson Fowler’s itinerary brought him back to Utah. On 11 December, one of Utah’s most ambitious young men, James H. Moyle, later a prominent lawyer and political leader, obtained a reading, borrowing two dollars to make up the five dollar fee. Here is what Moyle wrote in his journal:

As soon as he placed his hands on my head he said you should be a leader among men, told me in conclusion that nothing but success was before me. Said I was not conceited but was very far advanced in approbativeness. Said I should marry [a] wife that is rather stingy as I did not know how to keep money as I was extremely benevolent, one who would always say Yes! Yes! . . . Said I had immense brain measuring 23 1/6 inches. That I was a perfect steam engine, had wonderful vital force. Never stop[p]ed until I had thoroughly mastered any subject taken in hand. Was not satisfied with doing as well as others. Wanted to [do] more than anybody else. Said I would make a good clergyman. . . . Said I would make a good teacher, or politician or lawyer which he gives as preference if I natural[l]y leaned that way. . .. Advised me to eat less to be smarter.[27]

During the next few days young Moyle attended three different lectures by Fowler and bought one of the Fowler books. It is intriguing to speculate as to how much the examination influenced him in his choice of a career, for he did go on to study law and later entered politics.

Fowler returned again in 1884. Among those he examined in 1884 was William S. Godbe, one of the leaders of the Godbeite schism since 1869. Fowler said:

He has very positive characteristics. His positiveness is calculated to make him a great many enemies, and a great many friends. His enemies hate him to death, his friends love him correspondingly. He is a two-edged sword, a divider among the people. .. . He must be fighting something all the time. . . . Everything he feels and thinks must burst out like a young volcano. He cannot see anything he thinks wrong without pitching into it and holding on. . . . He is as stubborn as a mule and must not be driven or he will become more obstinate than before.

When a voice from the audience asked about his spirituality, Fowler responded that his spiritual proclivities were strong but “unlike those of others.” When Godbe asked about his conscientiousness, the professor, never at a loss for words, replied, “Your motives are substantially correct; I don’t say that all your actions are.”[28]

Examples could be multiplied. Mormons who received phrenological readings between 1840 and 1891 included Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, Wilford Woodruff, Willard Richards, Brigham Young, George A. Smith, Heber C. Kimball, Orson Pratt, John E. Page, Alfred Cordon, Elias Smith, James J. Strang, Matthias Cowley, James Bunting, James S. Brown, Joseph C. Rich, George Reynolds, Amasa Lyman, Charles C. Rich, N. V. Jones, George Q. Cannon, O. S. Clawson, E. L. T. Harrison, Edwin D. Woolley, Christopher Layton, Christopher M. Layton, William Blood, Jesse N. Smith, Sanford Porter, Andrew Jensen, Elizabeth Williams, John D. Lee, Orson F. Whitney, Franklin S. Richards, J. B. Toronto, James H. Moyle, William S. Godbe, William Spry, Daniel Wells, and Abraham H. Cannon. Some of these had more than one delineation.[29] Undoubtedly many others visited phrenological studios, but even with these names there is clear enough indication that many Mormons felt perfectly free to investigate what phrenology had to offer.

It would be a mistake to make too much of these contacts, which may have been about the same response as that of Americans in other parts of the country. But it is clear, at least, that there was no obvious incompatibility between Mor monism and phrenology. To understand why these Mormons might have been attracted to phrenology it will be necessary to review some of the assumptions and enthusiasms of phrenology during the nineteenth century.

The proponents of phrenology considered their work to be scientific—an effort to study mind, personality, and character objectively, quantitatively. Some of its assumptions were that mental phenomena have causes that can be determined; that anatomical and physiological characteristics have influence upon mental behavior; and that the mind is not unitary but is dependent upon localized functions of the brain. It is easy to see, perhaps, that such an approach to the study of human personality seemed an improvement over the highly impressionistic, subjective approaches of the past.[30] Moreover, as a recent writer has pointed out, “It was the first system that permitted detailed analysis of the human brain with out the inconvenience of autopsy.”[31] Since development of a particular area of the brain would manifest itself in a slight expansion of the cranium at that point, feeling and measuring bumps would provide an objective analysis of the person’s strengths and weaknesses. Or so it was believed.

It might be thought that phrenology was deterministic, one’s character being inevitably determined by his physiology. But in fact there was a strong “self improvement” strain, based on the assumption that faculties could be consciously developed through exercise. The notion of original sin, or anything like it, was quite foreign to the phrenologists, who accepted the notion of individual responsibility. In Fowler’s phrenological treatises each faculty is discussed in terms of the following categories: very large, large, full, average, moderate, small, and very small. One whose bumps had been measured could thus read a description of his own score on each faculty. But importantly each chapter concludes with specific advice under the headings “to cultivate” and “to restrain,” indicating that some thing could be done in the direction of improvement. The consistency of such assumptions with the Mormon thrust toward individual progress and self-perfection is obvious; although the advice given by phrenologists was not the only approach to improving oneself, it was specific, supposedly scientific, and quite consistent with Mormon morality. In practice, a phrenologist proceeded from the assumption that men were potentially good, potentially perfectable, and not borne down by the weight of original sin. Mormonism would find such ideas congenial.

Recognition of an interrelationship between the physical and the mental or spiritual led phrenologists to encourage the pursuit of health. Exercise was encouraged; simple wholesome foods were recommended; tobacco, tea, coffee, and alcoholic beverages were condemned. While such interests, exposed by the phrenologists in their lectures and periodicals, overlapped with other health movements of the age, it is obvious that early Mormons could readily agree with many of the recommendations. In a way, it might seem, the restored gospel and modern science were leading to the same conclusion.

The phrenologists were highly critical of medicine as it was practiced. In addition to simple “natural” foods and exercise they recommended various forms of hydropathy, the use of water to effect cures. Drinking of water, warm or cold, and the use of different kinds of sprays, washes, and baths were recommended. Some of these enthusiasms were shared by the followers of Samuel A. Thompson’s system of botanic medicine. Again it should be obvious that Mormons, with their hostility to the established medical profession, their preference for spiritual administration and hydropathy, and their receptivity to some of the Thomsonian precepts, would find a large area of agreement with the phrenologists.[32]

Interested in racial types, the phrenologists found a correlation between physical characteristics and traits of personality. Showing an incredible willingness to generalize, they lumped men within each race together under certain traits. One phrenologist, for example, explained the reluctance of the Indians to accept Christianity on the basis of the size and shape of their brains.[33] Physical characteristics in the final analysis were the consequence of moral choice, a naturalistic interpretation that is perhaps not far from the racial assumptions found in the Book of Mormon.[34]

Finally, consider the way in which phrenology was treated by the orthodox Christian clergy. Although individual clergymen were sympathetic and occasion ally even enthusiastic, the basic attitude was one of condemnation, as the Chris tian clergy denounced what they considered to be the atheism, materialism, and determinism of the phrenologists. To some extent the charges were valid although they were generally exaggerated and without real understanding. The phrenologists did not readily accept an immaterial reality, and in fact one branch of the movement was avowedly materialistic. Others accepted the point of view expressed by Edward Hitchcock: “It is as easy to see how an immaterial soul should act through a hundred organs as through one.”[35] This was close to the ridicule of “immaterial reality” by Orson Pratt and other Mormon leaders. Since both the Mormons and the phrenologists were scorned by the more respectable spokesmen of the Christian clergy, they had something in common. Actually the phrenologists were not atheists. Most of them agreed with Orson Fowler’s admiration of early, Biblical Christianity while they attacked the creeds and ceremonies of modern Christianity, which they saw as apostate.

In short, while Mormons could be attracted to phrenology by the same curiosity experienced by other Americans, they had in addition certain theological affinities, circumstantial alignments, and common opponents that help to explain the at traction. There seemed nothing in the way of an obvious incompatibility and at least suggestions of a complementary relationship.

In addition to these several affinities, phrenology offered one great attraction to Mormons through the nineteenth century. At a time when they were denounced and caricaturized by the press, when their public image was pitifully negative, here were men of national renown who treated them politely, recognized intelligence and strong character in their leaders, and were remarkably “non judgmental” in their comments on Mormon society. When the crusaders were making sweeping claims to the effect that polygamy resulted in inferior, handicapped children, for example, Orson Fowler’s claim that the Mormon children were normal must have been most welcome.[36] Inclinations to condemn phrenology must certainly have been tempered by the recognition that this science was valuable in promoting a relatively positive image of Mormonism.

Having recognized that more than a few Mormons showed some interest in phrenology and that the phrenologists had at least some interest in the Mormon leaders, we should recognize that as early as the Nauvoo period some Mormons were more than a little skeptical. In late 1841 a warning was printed in the Times and Seasons about Dr. William Campbell, alias Samuel Rogers, “a professed phrenologist.” This man was a member of the Church who had “got in debt as much as possible, until the latter part of November, when he borrowed a horse and some guns under the pretext of going a hunting, and left the country.”[37] This statement is hard to evaluate because financial irresponsibility was ample reason for condemnation. Two years later, on 6 May 1843, Joseph Smith had an interview with an unidentified lecturer on mesmerism and phrenology. His “history” notes briefly: “Objected to his performing in the city.”[38] On another occasion he challenged a believer in phrenology to prove the idea of localized functions of the brain.[39] These various brief encounters fall short of an outright condemnation, and the Prophet, as already noted, was willing to submit to examinations for the sake of “curiosity.” In 1843, Brigham Young described his visit to the Fowler studio in these words:

At the request and expense of Elder L. R. Foster, I visited Mr. O. S. Fowler, the phrenologist, at Marlborough Chapel, with Elders Kimball, Woodruff and Geo. A. Smith. He examined our heads and gave us charts. After giving me a very good chart for $1, I will give him a chart gratis. My opinion of him is, that he is just as nigh being an idiot as a man can be, and have any sense left to pass through the world decently; and it appeared to me that the cause of his success was the amount of impudence and self-importance he possessed, and the high opinion he entertained of his own abilities.[40]

In the Nauvoo Neighbor of 14 May 1845 we read the following:

Mr. McLeake has been feeling some of the heads at Nauvoo; nothing yet has been dis covered more than is common to the heads of other cities, only that the Navooans have large bumps of patience and wisdom.

Mr. McLeake has a touch of measuring the geography of the head as a carpenter would a barn, and then calculates the various appointments; and he calculates some things about right.[41]

This in the spirit of fun, not an angry rejection.

In William Smith’s newspaper the Wasp (Volume 1, No. 3) there is a description of Thomas Sharpe, leader of the anti-Mormon forces at Warsaw:

Tom Sharp’s snout is said to be in the exact proportion of seven to one compared with his intellectual faculties, having upon its convex surface fourteen well developed bumps.

These bumps signified fourteen traits, the fist among them being “Anti-Mormonitiveness.” Another take-off, reminiscent of Melville’s phrenology of a whale in Moby Dick.

A more serious answer to the claims of phrenology was advanced in the Millennial Star in 1864 by an Elder George Sims. His “Remarks on Phrenology” point out the tentativeness of any supposed scientific knowledge; the difficulty of interpreting the “bumps” satisfactorily; the Mormon belief that blood had at least as much to do with character traits as did the brain or the shape of the head; and that the faculties were not so important as the use to which they were put, a point with which the phrenologists would have readily agreed. An editorial note by George Q. Cannon reiterates some of the same points: the difficulty of correct interpretation, the importance of the Spirit of God, the impossibility of accepting phrenology as “a perfect science.” But these strong reservations did not stop Cannon from admitting, “We do believe there is some truth in phrenology.”[42]

Six years later, during the excitement aroused by the visit of Orson Fowler to Utah, Cannon was less than enthusiastic, to judge by his remarks before the school of the Prophets, as paraphrased by the secretary: “Elder G. Q. Cannon said as there was several Phrenogical [sic] Lectures going to be delivered in the city, he would just say that he did not believe much in that science, and hoped the Elders would not patronize them, especially in having charts of their own characters taken. Several once prominent members of the church have had their charts taken, and it seemed to puff them up so that they eventually apostatized, A. Lyman, W. Shearman, &c.”[43] This statement again seems to fall just short of a rejection of phrenology as such.

Interest continued among the Mormons, as indicated by various entries in diaries during the closing decades of the century. In 1876 a lecture on phrenology was given in the 8th Ward in Salt Lake City.[44] A few years later, in 1883, the Presiding Bishopric took notice as follows:

Enquiry was made of the standing and character of a Mr. Cederstrom who is going the rounds of the Mutual Improvement Associations, lecturing on the subject of phrenology and the testimony of Bro. Mortensen was that he was not a member of the church, having been cut off by Bp E D Woolley in the 13th Ward many years ago.[45]

Still, there is no indication here of condemnation of phrenology as such. It is apparent that over the years the Mormons had received conflicting signals from their leaders. On the one hand there were the various indications of skepticism and even statements coming close to condemnation of the phrenologists. But on the other hand prominent Mormons, including some general authorities, continued to obtain delineations. Moreover, there were scattered references to phrenology that did not take a stand one way or the other but at least appeared friendly. “We must learn to look ahead and live in anticipation, or as the phrenologists say, we must cultivate the bump of hope/7 said the Times and Seasons in 1845.[46] “As the phrenologists say”—such passing allusions occurred elsewhere.[47] And in some writings, especially those of Hannah T. King, the phrenological terms and assumptions appeared quite naturally.[48] It is not surprising if Mormons felt that phrenology had implicit institutional support. More accurately it enjoyed a suspension of judgment.

Toward the turn of the century two returned missionaries, Nephi Y. Schofield and John T. Miller, invested their energy in the study of phrenology. Schofield graduated at the top of his class from the Fowler-Wells sponsored American Institute of Phrenology. By so doing, he was designated a Fellow of the A.I.P. in October of 1896.[49] The following summer John T. Miller “graduated as a first class Scientific Phrenologist” from the Haddock Institute of Phrenology in San Francisco.

Soon Schofield began to apply his newly acquired skills. The Phrenological Journal of March 1897 reported: “The readers of the Salt Lake City Herald are being favored with character sketches of the leaders in that city, written by Nephi Y. Schofield, F.A.I.P., and well done they are too.”[50] He must have been extremely pleased when President Wilford Woodruff consented to a personal examination. President Woodruff’s phrenograph was written on 28 February 1897 and appeared later in the Phrenological Journal.[51] In the tradition of Fowler and Wells, Schofield did not confine his efforts to phrenological examinations. He submitted a scholarly paper to the New York Phrenological Conference and the paper was published in June of 1898.[52] The same issue contained a phrenological delineation of John T. Miller written by the editor, Jessie A. Fowler.[53]

When John T. Miller returned from his training in San Francisco he and Schofield opened an office in Salt Lake City. They advertised that one could get a phrenological examination as cheaply as a pair of shoes ($3.00). By November of 1898 Schofield wrote: “[I] am doing all the professional work that I can find time to devote to it, and in connection with Prof. Miller of Provo, Utah [I] am making a specialty of interesting and converting the school teachers and the educational classes of the State to Phrenology, and with encouraging success.”[54]

Anti-Mormons had occasionally used phrenology to attack Mormonism and its leaders. In 1902 Schofield found a different revelation from the principles of phrenology: “. . . science demonstrates clearly and conclusively that he [Joseph Smith] was not an imposter.”[55] But the most important event of 1902 for phrenology among the Mormons was the publication of a Western version of the Phrenological Journal—The Character Builder, destined to continue until the 1940’s. Miller and Schofield were the prime movers. These two Mormon phrenologists made successful inroads of acceptance, if not conversion, to phrenology within the educational community. The early issues of The Character Builder contained phrenological descriptions of the general superintendent of LDS Church Schools (Dr. J. M. Tanner), the superintendent of Salt Lake City Schools (D. H. Christensen), the president of Latter-day Saints University (Joshua Hughes Paul), the state superintendent of public instruction (A. C. Nelson), and other educational figures.[56]

The Human Culture Company was incorporated in November of 1903 with Miller as President and Schofield as Vice-President. The corporation was established to promote lectures, correspondence courses, summer schools and the sale of phrenological material. Among the prominent stockholders were Mr. Franklin S. Richards, the philanthropist Jesse Knight, the State Treasurer J. D. Dixon, the attorney Henry Lund, and “some of the leading educators of the Intermountain West.” By 1905 Miller and Schofield were “sending out about 60,000 copies of The Character Builder a year, besides several thousand books on human culture.” This must have been a circulation of about 5,000 per issue.

The Character Builder enjoyed some official Church support. In 1906 and 1907 the First Presidency sent copies to “a few hundred missionaries.” The Salt Lake Stake sent $108.35 m contributions. Miller summarized some of his success as follows:

Hundreds of stake and ward officers have testified to the importance of our lectures and the work of the Character Builder, and have aided with money, time and influence. A number of Bishops and Stake Presidents have invested $10 each. During five years $40,000 worth of character building literature has been circulated and thousands of our best crop— boys and girls—have been led to purer thinking and nobler living. Our work fits into all organizations; requests for lectures come to us from parents’ classes; religion classes; M. I. associations; elders and seventies’ quorums; lesser priesthood and relief societies. In visiting the wards to give lectures we frequently hear bishops and other workers say that no work is more needed than this.[57]

It should be observed, however, that Miller was attempting to raise money and was obviously concerned about the possibility that the venture would collapse. Furthermore, phrenology was not mentioned specifically in the letter; typically it came across in indirect and diluted form or in the phrenographs printed in the magazine.

Nephi Schofield dropped out of sight, perhaps due to differences with Miller, perhaps due to his duties as credit manager at Z.C.M.I., which started in 1914.[58] The same year Miller moved to Los Angeles. But some Mormon support continued. On a lecture tour through Oregon and Idaho in the summer of 1918, Miller was invited to speak at two quarterly stake conferences and his lectures were arranged by the presidencies of the Raft River, Curlew, Blackfoot, Bannock, and Oneida Stakes.[59] Miller’s phrenological articles appeared in Church periodicals in 1910, 1912, 1919, and 1929.[60] The October 1927 Character Builder was devoted to the “phrenologist” Karl G. Maeser. Maeser had used the language of phrenology in his book School and Fireside (1898), and Miller did not forget it.[61]

Among those whose phrenological readings were published between 1903 and 1918 were Orson F. Whitney, Lulu Green Richards, F. W. Openshaw, Zina D. H. Young (from a photograph), Mrs. F. S. Richards, Charles R. Savage, Dr. John R. Park, President J. T. Kingsbury, Evan Stephens, and (from a photograph) Eliza R. Snow.[62] Phrenology was still clearly associated with some prominent and respect able Mormons.

The 1930s and 1940s must have been difficult years for the committed Mormon phrenologist. More adequate scientific explanations of human behavior were being put forth, and modern psychology was being introduced into the academic institutions of Mormon country. Full of frustration, John T. Miller wrote in 1938 to Apostle Reed Smoot, a member of the Brigham Young University board of trustees.[63] Desperately trying to benefit from the reputation of Karl G. Maeser, the great educator, Miller wrote, “I think the time is ripe to begin a revival of Dr. Maeser’s work. . . . The BYU should lead the world in such a revival but they have nobody trained to teach that science.” Miller saw himself as defending “the true science of mind that has been lost to the world” from “the vicious behaviorism of Dr. [John B.] Watson.” To this end he had given lectures at BYU, where he had received a cordial reception except for one “young psychologist” (Prof. Wilford Poulson). Miller wrote to Apostle Rudger Clawson, who presented the letter to the Council of Twelve. The Twelve then referred the matter to the First Presi dency with a recommendation that the question be investigated. Miller noted that David O. McKay admired his “fearlessness” and added that John A. Widtsoe was “very friendly” to his work. Then Miller appealed to Smoot: “You having been a student of Dr. Maeser . . . are the logical man to lead in a movement that will revive the spiritual education of Brother Maeser. . . .”

But the proposed phrenological revival did not get off the ground. There was no room for phrenology in the respectable departments of psychology, and neither Apostle Smoot nor any other leader was apparently disposed to take up the banner Miller was trying to pass on. The death knell of phrenology among the Mor mons was sounded in November 1940, when The Character Builder under the heading “Phrenology Outlawed” sadly noted: “The old city governments in the cities of the Angels and Saints made it a crime to use the true science of life.” The crowning blow was the Deseret News’s refusal to print Miller’s rebuttal.[64]

If phrenology was ultimately treated mainly as a curiosity by most Mormons, this was due largely to the adequacy of Mormonism as a theology and a religion. The Mormon leaders, those who might claim to be spokesmen, always refrained from fully embracing the “science.” Individuals who were more enthusiastic were on their own, so to speak, taking their own chances. As long as there seemed to be some scientific support for the assumptions of phrenology, it could appeal to individual Mormons, but by the early twentieth century it was losing whatever respectability it once seemed to have. It is an indication of self-confidence and internal adequacy that, with respect to phrenology at least, Mormonism had never gone overboard.

It may be worth noting that some of the appeals of phrenology were already supplied by Mormonism in other ways. The thrust for self-improvement and education were already present in Mormon thought and did not require phrenological underpinnings. Those who sought examinations were interested in their personal characteristics, aptitudes, and potentialities. The phrenological reading seemed to offer a combination of fortune-telling and vocational aptitude test under the guise of scientific objectivity. It was personalized, based as it was on a careful examination and measurement of one’s head. A highly personal message was the expected result. But Mormonism already had something that accomplished much of the same purpose—the blessing from a patriarch, who would place his hands on one’s head and pronounce words referring to past lineage, present status, and future possibilities, not on the basis of scientific measurement but by divine guidance. In experimental terms, however, the results were quite similar. The blessing was highly personal, was trusted in, and served as a guide and an inspiration. Obviously, those having faith in this whole process would find the patriarchal blessing at least as reliable as the phrenological examination. Without question far more Mormons obtained patriarchal blessings, copied them in their journals or otherwise cherished them, than obtained readings from phrenologists.

For a few years, then, phrenology aroused interest among some Mormons as it did among other Americans. A few Mormons were enthusiastic and found a complementary relationship between their religion and this pseudo-science. Most benefits of phrenology were already available to Mormons on other grounds, however, and with the fading of phrenology’s scientific responsibility it lost its appeal. The refusal of Mormon leaders to subscribe to causes and movements such as phrenology could have its disadvantages at times, for they could seem to be unreceptive to the science and progressive causes of their day. But in the final analysis such a reserved attitude prevented the Mormon religion from becoming too closely linked with fads and temporary enthusiasms and was a source of strength.

[1] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 6 vols., (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1949), 5:52-55. We have quoted above from the handwritten version in the Church Archives. The published version contains slight editorial alterations in brackets, as follows: “I give the foregoing a place in my history for the gratification of the curious, and not for [any] respect [I entertain for] phrenology.”

[2] John W. Davies, Phrenology Fad and Science: A 19th Century American Crusade (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955), p. 37. See also Madeleine B. Stern, Heads and Headlines— The Phrenological Fowlers (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971), pp. 17, 62, 134.

[3] Alfred Woodward file, Archives of the Historical Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter referred to simply as Church Archives). This file contains three handwritten versions of the Woodward phrenograph: the original charts of Woodward, a copy by Philo Dibble, and a copy found in the papers of John Taylor. The “faculties” are de nominated according to the standard phrenological usage of the time. For definitions see any early book on the subject, as, for example, O. S. and L. N. Fowler, Phrenology: A Practical Guide to Your Head (Reprint, New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1969).

[4] Smith, History of the Church, 6:56. Inconsistency between readings was one of the factors arousing Mark Twain’s skepticism. “I am aware that the prejudice should have been directed against Fowler instead of against the art; but I am human and that is not the way that prejudices act. . . .” Neider (ed.), The Autobiography of Mark Twain, b\it.

[5] The Wasp, 9 July 1842 (Willard Richards); 16 July 1842 (Brigham Young). These readings can be found printed in Smith, History of the Church 5 158-60 and in E. J. Watson, ed., Manu script History of Brigham Young (Salt Lake City, 1968), pp. 118-20.

[6] Wilford Woodruff Journal, Church Archives. Volume and page numbers are not supplied in journal references where the date of entry is adequate as a means of locating the passage.

[7] Who called on the Fowler studio for an examination on 20 September 1843? There is a slight discrepancy in the sources. All agree that Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and George A. Smith were among the number. A letter from George A. Smith dated 19 September (Church Archives) says that Orson Hyde and John E. Page were also there. Joseph Smith’s history, compiled by his scribes, does not mention Page but does mention Orson Pratt. (Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints [Salt Lake City, 1950], 6:37). Brig ham Young’s history omits mention of Hyde, Page, and Pratt but mentions Wilford Woodruff. E. J. Watson (ed.), Manuscript History of Brigham Young, pp. 150-51. Wilford Woodruff says that “the Twelve” called at the Fowler studio, probably meaning those of the Twelve who were in Boston at the time. Woodruff Journal, Church Archives. Perhaps there were several visits; the examination of George A. Smith as found in the Church Archives is dated 14 September 1843.

[8] “Though the Editor never examined the head of Joe Smith, he has minutely examined, and will sometime lay before his readers, the developments,, phrenological and physiological [,] of Hyrum Smith, which unquestionably were strongly allied to those of Joe except less strongly marked.” American Phrenological Journal, 7 (1845), 298. (Hereafter APJ.)

[9] James M. Monroe Diary, MSS 343, Coe Collection, Beineke Library, Yale University. Juanita Brooks has assembled some biographical information on Monroe in On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 1844-1861, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1964), i:i2n.

[10] Strang’s phrenology was published in the first issue of the Northern Islander. For excerpts from this document, a remarkably perceptive evaluation of Strang, see Robert P. Weeks, “For His Was the Kingdom, and the Power, and the Glory . . . Briefly,” American Heritage, 21 (June 1970), 4.

[11] AP7,17 (1853)/ 47-

[12] Martha C. Cox Journal, holograph, pp. 83-84, Church Archives.

[13] APJ, 37 (1857), pp. 58-62,112.

[14] APJ, 49 (March 1869), 109-110, as quoted in Madeleine B. Stern, “A Rocky Mountain Book Store: Savage and Ottinger of Utah,” Brigham Young University Studies, 9 (Winter 1969), 144-54.

[15] APJ, 51 (January 1871), pp. 44-45.

[16] The Illustrated Annuals of Phrenology and Physiognomy (New York: Samuel R. Wells, Publisher, 1871), pp. 38-40.

[17] Edward Tullidge to Brigham Young, 14 May 1867, Brigham Young Papers, Church Archives.

[18] APJ, 51 (July 1871).

[19] Tullidge was in communication with E. L. Davenport of the office of the Phrenological Journal. Tullidge to Davenport, 9 May 1871, photocopy of holograph, Church Archives.

[20] Salt Lake Daily Herald, 27 January 1872. We are indebted to Noel Barton for calling our attention to material on the 1872 visit of Orson Fowler.

[21] Salt Lake Daily Herald, 31 January 1872.

[22] Salt Lake Tribune, 30 January 1872.

[23] Salt Lake Daily Herald, 6 February 1872. Poking fun at phrenology was a national pastime. Oliver Wendell Holmes described a visit to the studio of “Bumpus and Crane” and had great fun with the outlandish phrenological terminology. Even funnier is Mark Twain’s description of how one phrenological bump would almost inevitably be neutralized by its opposite and how the examiner, to his great surprise, found Twain’s head to contain a cavity in one place instead of an expected bump. “He startled me by saying that the cavity represented the total absence of the sense of humor!” Stern, Heads and Headlines, pp. 131-33, 183-85. However, as Stern demonstrates, both Holmes and Twain were quite capable of taking phrenology seriously.

[24] Salt Lake Daily Herald, 6 February 1872. “He has drawn very large audiences during the entire course” (Salt Lake Daily Herald, 27 January 1872). The lecture “was attended by a very large audience” (Deseret Evening News, 15 February 1872).

[25] Deseret News Weekly, 7 February 1872. For a later, equally cautious, statement by Fowler on this same question, see the Territorial Enquirer, 13 June 1884.

[26] Salt Lake Tribune, 31 January 1872. Cf. the suggestion that Fowler should examine the heads of the Mormon leaders in a public demonstration. “If the celebrated Fowler got into Brigham’s head, he would find another Mormon problem. He would discover large causality, comparison, humor, agreeableness, human nature, benevolence, veneration, spirituality, hope, no organic lack of conscientiousness, small self-esteem and strong social sympathies; and what the deuce Fowler could manage to do with this group of organs we don’t know, unless he overbalanced them with large destructiveness, acquisitiveness, secretiveness, will power, ambition, tremendous jaws, eagle nose and a lion mouth that could bite a head off.” Salt Lake Tribune, 30 January 1872.

[27] James H. Moyle Journal, Church Archives.

[28] Deseret Evening News, 4 June 1884.

[29] Specifk dates and documentation for these phrenological examinations have been arranged in tabular form. The authors of this article will appreciate hearing of additional specific examples.

[30] Davies, Chapter 1.

[31] Andrew E. Norman introduction to reprint of O. S. and L. N. Fowler, Phrenology: A Practical Guide to Your Head (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1969), p. vi.

[32] For a few indications of hydropathy among the Mormons see Ogden Kraut, A Brief History of Rebaptism (Dugway, Utah: n.d.), pp. 8-10.

[33] Davies, pp. 154-56.

[34] Not only do the “curses” experienced by the Lamanites in the Book of Mormon fall into this category, but the whole Mormon effort to relate human races to supposed actions in the pre-existent state asserts physical consequences to moral choices.

[35] Davies, p. 151.

[36] J. H. Beadle, for example, saw the deleterious effects of polygamy in the “strange dullness of moral perception, a general ignorance and apparently inherited tendency to vice” on the part of the Mormon children. Quoted in Kimball Young, Isn’t One Wife Enough? (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1954), p. 24.

[37] Times and Seasons, 3 (December 1841), 638.

[38] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City, 195°)/ 5 :383- The following words in the handwritten version were crossed out and not included in the published version: “thought we had been imposed upon enough by such kind of things.” History of Joseph Smith, Church Archives.

[39] Joseph Smith, History, 6:56.

[40] E. J. Watson, ed., Manuscript History of Brigham Young, pp. 150-51.

[41] This was P. S. McLeake, whose phrenology of Elias Smith is available (photostatic copy) at the Western Americana collection, Marriott Library, University of Utah. According to James M. Monroe, McLeake “says he is going to be baptized and settle here [in Nauvoo].” Monroe Diary, 13 May 1845.

[42] Millennial Star, 26 (1864), 451-54. The editorial addendum can be ascribed to George Q. Cannon on the basis of internal evidence, p. 454.

[43] Minutes of the School of the Prophets, 20 January 1872, Church Archives.

[44] Salt Lake Stake Deacons Quorum Minutes, 1873-77, entry for 11 April 1876, p. 182. #1809, Church Archives. Olof Cedarstrom (or Oluf Cederstrom), the “widely known professor of phrenology,” died at age eighty in Lehi in 1908. Deseret News, 1 May 1908 and 5 May 1908. He seems to have immigrated to the United States in 1857. Emigration Records of the Scandinavian Mission, 1854-63, p. 50. He did not come to Utah until 1863. Perhaps it was during this intervening period that he learned phrenology. On 7 September 1864 an Oif [?] Cedarstrom was fined for giving whiskey to the Indians. Journal History, 7 September 1864. We are indebted to Richard Jensen, research associated of the Historical Department of the Church, for these details.

[45] Presiding Bishopric Meeting with Bishops and Lesser Priesthood Minutes, 1879-1884, Church Archives.

[46] Times and Seasons, 6 (1845), 981.

[47] Times and Seasons, 5 (1844), 468; Woman’s Exponent, 10 (1882), 147.

[48] Hannah T. King’s “portraits” are in Woman’s Exponent, 8 (1879), 6y, 75, 83, 91, 102-03.

[49] APJ, 103 (January 1897), 49.

[50] APJ, 103 (March 1897), 144.

[51] APJ, 106 (December 1898), 193-95.

[52] APJ, 105 (June 1898), 183-86.

[53] APJ, 105 (June 1898), 181-83.

[54] APJ, 106 (November 1898), 169.

[55] The Juvenile Instructor, 37 (1902), 261.

[56] The Character Builder, 4 (May 1903), 13-16; 4 (October 1903), 195-97; 4 (January 1904), 314-16; 5 (August 1904), 107-09.

[57] John T. Miller letter, 15 November 1907, BYU Archives.

[58] Obituary in Salt Lake Tribune, 29 July 1940.

[59] “The Editor’s Lecture Tour,” The Character Builder, 31 (1918), 306-08.

[60] “Marriage Adaptations,” Young Woman’s Journal, 21 (1910), 98; “The Mirror of the Mind,” Young Woman’s Journal, 23 (1912), 547-49; “Character Analysis of President Brigham Young,” Young Woman’s Journal, 30 (1919), 330-32; “Character of President Brigham Young,” Improvement Era, 32 (June 1929), 639-41.

[61] Karl G. Maeser, School and Fireside (Provo, Utah, 1898), pp. 14, 314.

[62] The Character Builder, vols. 3-5,18, 24, 30-31.

[63] John T. Miller to Reed Smoot, 26 August 1938, John T. Miller file, University Archives, Brigham Young University.

[64] The Character Builder, 48 (November 1940), 25.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue