Articles/Essays – Volume 23, No. 4

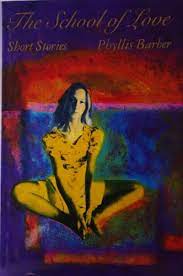

Strange Love | Phyllis Barber, The School of Love

Disparate voices of contemporary short story writers, among them Alice Munro, Margaret Atwood, Raymond Carver, Louise Erdrich, and even Mormon author Linda Sillitoe, all use external situations to probe the inner life of characters. All are authors busy with nuances of the craft, sharing at the very least a concern with characters in credible, if sometimes minimal life situations. In this reading context, I found Phyllis Barber’s collected stories in The School of Love to present eccentric, strange territory in the land of current fiction. Though many of her stories begin in the “real” world, they drift into a landscape of dream and fantasy — worlds where the familiar suddenly becomes unfamiliar, where sanity approaches madness, where time warp defies chronology, where known intersects with unknown, and understand ing takes on private symbology that calls for translation. Yet we’ve all traveled in these realms not real, and they reflect in an eerie way the deepest of our personal realities.

Many people read fiction to learn about human behavior; Phyllis Barber’s stories call upon us to learn about the human heart—especially about our own hearts. That’s why, the more I think about it, her title seems entirely apt, even though when I first read the collection I wondered. Surely someone looking for conventional boy-meets-girl romance would find the title puzzling, if not misleading. For here we are schooled in love that defies conscious expression — love that wells up from the subconscious and that we only half recognize.

Barber’s dual epigraph, “God is love” (1 John 4:8) and “Love is strange” (Sonny and Cher), points to her indefinable mix of the sacred and the profane, the rarefied and the downright strange. Take the story “Tangles” for instance. The nymphet child, Alice, sleeps with her teddy bears — palpable bears of gray and brown and white. The white bear even has a music box inside. And Alice’s father is real enough too —no dream daddy at all, but one who types and scolds and gives advice, and whose balding head Alice kisses. But what of the figures who are less certainly real? There is the man who follows her home from school and who reappears at various points in the story. He wants to touch her golden hair—to braid it, she thinks, into a cord and to lead her away. What part of this man with “yolky” eyes is real, what part nightmare, what part a girl’s surreal conception of the men her father says “only want one thing”? Is he archetype or actual; sinister or holy? One moment (in dream or in reality) the man narrows his unnatural eyes to scream, “Respect for the man”; the next moment he is kissing Alice’s cheek, kneeling holily and whispering, “Love one another,” and then, Christ-like, lifting her up while reassuring her, “Be not afraid” (p. 22).

Here is a girl on the brink of sexual love, frightened, confused, mixing the little girl love she’s known with mysteries of sacred love and with the equally strange adult love to which she now must be initiated. The only male/female love she’s known till now has been for her bears (who all seem to be Teddies) and for her father—all of this getting bizarrely mixed up in her rite of passage. We’re told that Alice joins the circus. We’re told that The Dwarf there fondles her with his “nubbed digits,” “kneading” and “tweaking” between her legs until The World’s Big gest Lady interrupts and they go back to their game of canasta. Violation seems to happen in a stuffy tent, or does it rather happen in a nightmare enactment of Every woman’s fears? At one point in the story, we do know for sure that Alice has crossed the line between sleeping and waking. In this identified dream-vision, Alice’s father becomes one with the bears, his mechanical wind-up words proclaiming, “I love you most of all”—something per haps most every girl subconsciously wishes could be true—that love could be for a known and gentle father rather than for a strange and threatening man.

This father/daughter motif appears in two other stories in Barber’s collection — “Silver Dollars” and “The Glider” — where it is again clear that father love goes beyond filial devotion. This archetypal theme is not one that women freely discuss or even consciously admit; it brushes too close to the taboo. But it does well up as a familiar in Barber’s impressionistic tales; at least it did for me. Other readers will find their own meanings; Barber demands that sort of reader participation. She says as much in her artistic credo (“Mormon Woman as Writer,” Dialogue, Fall 1990), implicitly embracing as her own goal, Mario Vargas Llosa’s description wherein “the truth (one or several) is hidden, woven into the very pattern of the elements constituting the fiction, and it is up to readers to discover it, to draw, by and .. . at his own risk the ethical, social and philosophical conclusions of the story” (p. 110). This accurately describes Barber’s own method. In her Dialogue essay she reiterates that “much of the bur den of interpretation lies with the reader who will make out of words what he or she wishes” (pp. 112-13). If Barber’s stories, so wondrously diverse and imaginative, have a formula, it is this —readers must be engaged in the intricate weaving process, must add their own strands to the warp of fantasy, the weft of reality.

Though Barber’s stories in their wild imaginative flights defy ready classification, each does have commonality with what Carlos Fuentes has called the “privileged” language of fiction—providing access to life centers that we do not and cannot read discursively. People who choose not to understand fiction deny its unique psychic language—symbology that can bring us a deeper understanding of things we may not always want to hear, helping us to discover qualities and meanings not always apparent even to ourselves. Another commonality is that all central characters are girls or women involved in a quest for some aspect of love—females in archetypal stages of love.

Each of the stories in this collection deserves separate and close analysis: each deserves time and engagement. Meanings are not readily or conventionally accessible but require tapping of our deeper, sometimes suppressed sensibilities. While the story “Tangles” is unique within this set of unique stories, it does typify some aspects of the whole. In “Silver Dollars” and in “Tangles,” we see teen girls on the brink of passage to womanly love, trying to use father love as a model, yet trying to break away from that familiar love as well. In “Love Story for Miriam” and in the brief impressionistic piece, “Almost Magnificence,” we see spinsters who for one reason or another have been denied the passage to romantic love. In “Baby Birds,” we observe mother-love that is unstinting. “Anne at the Shore” (a wonderful self-creation myth), “Criminal Justice,” and another mere glimpse, “White on White,” all explore self-love thwarted, discovered, or created, and in the three thematically related stories, “Radio KENO,” “Oh Say Can You See,” and “The Argument” (another fragment), we read of love that has run amok in motive and manifestation.

Again, Barber’s discussion of her own technique defines her approach as candidly as any author’s confession of method I’ve seen. Read her collection with the following apologia in mind:

I like to explore time warps, the edges of sanity, impressionism, experimental language, oblique approaches to the subject of humanity. I like subtlety more than dramatic intensity. I believe that truth is found in small places, not always in heroic epics. I am attracted to stories with barely discernible plot lines. Maybe this is because I, as a woman, have learned to survive by not being obvious. It threatens me to be seen too clearly. Sometimes I adopt bizarre imagery and situations in my fiction, maybe hiding behind a veil of obfuscation. Maybe this could be considered a female ploy—an invitation to “Come in and find me.” (1990, 118-19)

If Phyllis Barber’s fiction is deliberately obscure, it is never coy. Go into The School of Love and find her; go in and find yourselves.

The School of Love by Phyllis Barber (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1990), 113 pp., $14.95.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue