Articles/Essays – Volume 10, No. 3

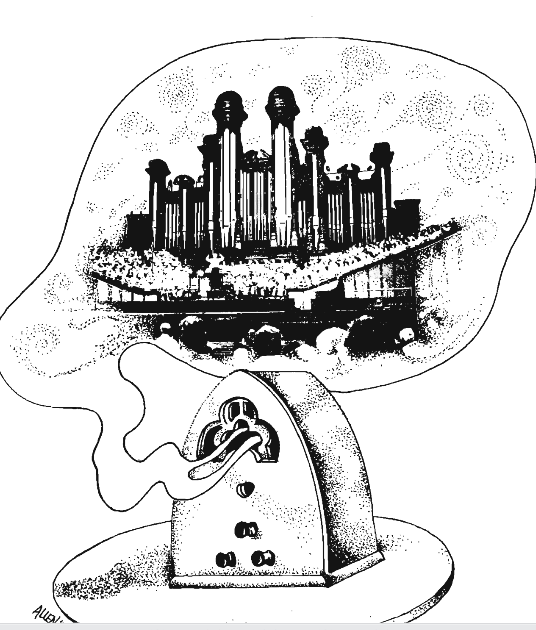

The Church as Media Proprietor

Small wonder that churches use the mass media as a broad-based platform for information and persuasion. The communications marvels of our century make it possible for the LDS Church to reach a wide audience indeed, even a worldwide one, and the revolution in delivery systems is still in its infancy.

It is sometimes suggested that the pulpit has actually been replaced by the media, and this observation has some merit, although the media are by no means all-powerful. They have become indispensable in “setting the agenda”—deciding what topics society will discuss (with the pulpit often taking its cue from media reports). Information on television and radio and in the papers make it possible for people to find a way of sharing values and moving toward goals. The media give people information they need just to cope with daily life.

The Church benefits not only as a user but also as an owner of community newspapers and broadcasting outlets. Through them it can express a viewpoint in a calm and continuing way without directly committing its leaders. Through them it gains direct access to the community without having to become either supplicant or purchaser.

On the other hand, there are drawbacks to being part of the communications industry. The first is that all media are under assault. Their motives, methods and consequences are being examined, often under fire, and a burgeoning literature about journalism is often uncharitable and hypercritical. Television is accused of pandering to the basest tastes, of corrupting morals and focusing on the antisocial—especially the violent—as well as the irrelevant and transitory. Some critics see television’s banal situation comedies and action adventure programs as dangerously proselyting an ethic all their own. Similarly, critics believe the press can deliver more thorough and believable news that show the positive dynamism of human affairs.

Some virulent criticisms are overstated, yet no church should ignore them even if it is not a media entrepreneur. Some critics shout that media values are essentially un-Christian. If they are correct, the church message itself can be adversely perceived: As Jefferson observed in one of his darker moments, the truth itself becomes suspect by being put in a polluted vehicle. A message has to come from a credible source if it is to be believed and acted upon.

The second risk for the proprietor is that readers, listeners and special interest groups demand the medium be an outlet for their views, however self-serving, however much at variance with those of the church. Unless they are responsive to these pressures, church media, such as KSL and the Deseret News, face the charge of being mere propaganda vehicles—an especially sensitive point in the broadcasting industry, which is obliged by law to provide broad-based opportunities for community discussion and rebuttal. Such criticism is especially cutting when the proprietor also operates a conglomerate, as the LDS Church does through its ownership of a daily newspaper, AM-FM and TV broadcasting stations and interlocking arrangements with other media in Utah. Because the airwaves presumably belong to everyone, failure to program in the broad public interest invites loss of a licensee’s permit. The argument is also being advanced that the same requirements be imposed on the print media, although a “right of reply” for candidates for public office has been rejected by the Supreme Court.

Not many churches take such risks. The LDS Church is almost unique in operating a community-oriented media conglomerate in addition to its public relations arm, film-tape distribution system, book publishing and filmmaking enterprises.

The Ministering Media

Within the LDS Church are controlled publications ranging from mimeo graphed newspapers to the Church News and the church magazines. Church newspapers and magazines do not attempt to portray the whole human comedy or offer something for everyone. Usually they do not tackle hard and controversial issues, and they take a cautious and even reverential stance toward church leaders. They are primarily psychological community centers that emphasize success stories and reinforce the church message. Any church press can enlarge on such a function only when authority and membership are receptive to criticism and change. Thus some of the major denominational magazines, such as Presbyterian Life, The Lutheran and The Episcopalian get high marks not only for technical excellence but also for willingness to discuss hard, secular and religious issues.

Church radio and TV programs are usually bland as well. They can be faulted for lack of a consistent point of view. It can be argued that despite thousands of hours allocated to church programs as a public service obligation, what is broadcast in the name of religion is often neither good religion nor good broadcasting.

Because church ownership of daily newspapers has never been significant in the United States, the Deseret News is really an anomaly, born in a theocracy and continued as a sort of universal joint between the church, its members and an increasingly secularized world. The Christian Science Monitor, to be sure, endures, but it is more a newsmagazine than a general newspaper, and is pitched above the daily rancor reflected elsewhere in the press.

Perhaps the closest parallel to the Deseret News is L’Osservatore Romano of Rome. Nearly as old as the Deseret News—it was founded in 1861—it too began almost as an accident of history when the Pope was temporal king of the Papal States of Central Italy. It too answered critics of the hierarchy and became the unofficial voice of its church, operating through the leadership’s lay intermediaries. Its policies reflect the Church’s but it does not speak directly for the Pope. Throughout Western Europe, which has a long tradition of church political parties and a supporting press, newspapers are freeing themselves of direct party and church ties and are seeking wider audiences.

There is such an incredible harvest of richness and diverse reading in the better newspapers—and I would include the Deseret News—that one is tempted to avoid the discussion of whether or not the press does in fact fall short of its most essential function—that of giving an accurate, unbiased and reasonably comprehensive view of the world. It is fairly easy to get an audience by focusing on concrete, overt events and engaging personalities—even events contrived to call attention to themselves. It is much more difficult to illuminate processes that explain the forces that gave rise to the event.

News selection is further complicated by the huge increase in the range of problems that should concern everyone in an interdependent society. These put a tremendous strain on organs of information. Really important processes take a long time to gain public identity and focus. It is not until these processes affect great numbers of people that the media, as a rule, report them comprehensively. Hence the blind spots in reporting on great movements like black liberation and the woman’s movement. The comfortable habits of reporting passing events are not at all adequate to reporting, much less giving background and predicting such news in our dangerous and complex world.

The special pleader has therefore learned to manipulate the media because he or she understands the limitations and the needs of the media’s approach to news. The demonstrator, the impresario of the pseudo event, the noisy dissident all can call attention to their causes. The media today face a special obligation to avoid being used and to avoid creating events by the mere act of report ing them.

Can newspapers and broadcasting outlets break out of traditional molds of gathering and presenting information? Yes, but not quickly or easily. They are tied to similar sources of news, similar ways of gathering and presenting information, similar syndicated and network arrangements. The Deseret News can effect only modest improvisations upon what it receives from news and syndicated sources and in how it covers the news—advertising acceptability standards being a bit more stringent than in most papers. There is very little difference in coverage between The Salt Lake Tribune and the News. The Tribune covers the Church almost as completely and only a little less deferentially. The differences are chiefly in emphasis and technique. The similarities were especially pronounced in the way both papers covered the Allan Howe incident, even though it presented highly discretionary legal and ethical dilemmas for the press.

If we are disheartened by the way the media cover political campaigns and some other aspects of government, we can be reassured by the way the adversary relationship between government and the press has worked to preserve freedom. We can also point to the increasing willingness of people to recognize that the press not merely reflect life but superimposes a value scheme on what it chooses to report. Press meetings and journals still emphasize problems of freedom, as they should, but they also deal with media responsibilities and possibilities. Taken as a whole, and discounting the too-raffish, lunatic and sensation-seeking fringe, newspapers are much less frivolous than they were a generation ago and incomparably more reliable and interpretive than 50 years ago; and TV, despite some lamentable lapses and a propensity to over-report, some times betters the print media.

In this imperfect world, operating a community mass medium has to be viewed as something of an expression of faith in the ultimate prevalence of truth, a doctrinal point in the LDS Church and one of the cherished assumptions of the democratic process: John Milton’s ideal of the truth ultimately emerging from the welter of competing tongues and persuasions, the pollsters view that over the long haul people act rationally in their own best interests and society’s if they can get the right information. Watergate tested these assumptions and validated them.

In a 1968 document, the World Council of Churches recognized that as instruments handled by human beings, the media often will be less than totally adequate. It urged that churches lay aside suspicions and invest time and money to help raise the standards of the media and to involve themselves with news organizations. These are outlooks consistent with the long-time willingness of the LDS Church to face the risks the media present.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue