Articles/Essays – Volume 08, No. 2

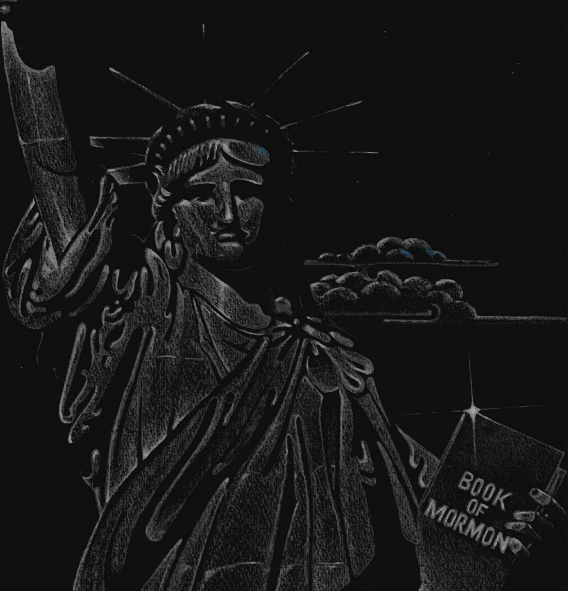

The Gospel, Mormonism and American Culture

This issue of Dialogue emphasizes the relationship between Mormonism and American culture. John Sorenson’s lead article on “Mormon World View and American Culture” sets the stage by attempting to make a distinction between the gospel perspective and the culture of the United States. He tries to determine those aspects of the restored gospel that are unique so as to separate them from those cultural values Mormons sometimes confuse with the gospel.

This theme is reflected in most of the other pieces in this issue. In her short story, “The Willows,” Eileen Kump writes about a period in our history when Mormons prided themselves on their uniqueness and in which, out of necessity, they separated themselves from the rest of America and vigorously resisted any incursions into their mountain fastnesses. Some Mormons in the Great Basin Kingdom didn’t even consider themselves Americans, and at times openly resisted the government.

A contrast between that time and the present is seen in Mark Leone’s article, “Why the Coalville Tabernacle Had To Be Razed.” Leone argues that the ease with which the Church tore down one of its most beautiful historic buildings is related to the extent to which it has adapted itself to the modern world and suggests that it is this very adaptiveness which may explain the Church’s continuing vitality. Not all Mormons will agree with Leone, however, as evidenced by Frederick Buchanan’s note on Cornerstone, a group of Latter-day Saints who are “dedicated to the preservation and continued use of buildings having a significant historic and aesthetic place in the Mormon experience.”

In his essay “Good-bye to Poplarhaven” Edward Geary attempts to illustrate that American culture is making new inroads to the fields of Zion, with encouragement from the Saints, who seem all too willing to give up their clean air and clear water for a greater share of American technological progress.

Michael Coe, a distinguished non-Mormon anthropologist and archeologist, presents some outspoken views on the extent to which Mormons, in their zeal to prove the gospel, have used archeological “evidence.” As critical as Coe’s views are, they represent an important side of the Mormon-American dichotomy.

In the Letters to the Editor section and in a lengthy letter in Notes and Comments by Martin Gardner there is a continuing dialogue on Mormonism’s Negro doctrine, a significant case study in the Mormon-American culture debate. Some have felt that the Negro doctrine is clear evidence of the influence of American culture on the Church, and others have argued that the Church’s refusal to bend to contemporary cultural pressures to change the doctrine is a clear sign that the Church is not influenced by culture.

All of these writings demonstrate that the relationship between Mormonism and American culture is a highly significant one, and, as Sorenson tries to show, one that we must seek to understand. In a larger context it can be seen as part of a conflict that has always existed between the way of the world and the way of the Lord.

The problem of being in the world but not of it has faced the children of God in every generation. Rather than live with such a conflict some have sought safety by secluding themselves from the country of the worldly and, like the nun in Gerald Manley Hopkin’s poem “Heaven-Haven,” have fled “to fields where falls no sharp and sided hail/And a few lilies blow.” Trusting neither themselves nor the world, such persons seek safe and secret islands of the mind and the spirit. Others, caught by the lure of lovely and lascivious things, venture into the enemy’s territory never to return. Like the profligate young Augustine they find the world’s “cauldron of unholy loves” too inviting.

Those who find neither of these options acceptable have the most difficult and perhaps most dangerous lives, for they must live with the conflict between cultural customs on the one hand and gospel principles on the other. Those who face this conflict do not seclude themselves from the world nor surrender to it, but attempt to stabilize their lives between these extremes. To do this they must have a clear understanding of the gospel as well as the culture in which it is lived. With out such an understanding the two become confused and the demarcations between them indistinct.

An example of this can be seen in the response of some Christians (including Mormons) to the recent corruption in American government at the highest levels. Those who have been apathetic toward these events or who have gone to great lengths to rationalize them have allowed the gospel perspective to be overshadowed by indifference or partisan politics. The gospel allows for neither of these responses, for the Christian’s duty is to counter corruption in all its forms and to avoid neutrality on any moral issue. As Thoreau said, “There is never a moment’s peace between vice and virtue.” In a recent address in which he referred to “these troubled times—a Watergate, and lying . . . and deceit, and immorality and a breakdown of decency and of law and order in our country,” President Harold B. Lee suggested that it was precisely the gospel principles that form “the foundation that you . . . need in order to stand up against these things that are rolling past, rolling as an avalanche of filth and an undercurrent that threatens the very basic foundations on which this country has been founded” (italics added).

President Lee’s remarks emphasize the fact that the Church has a significant role to play in the conflict between the gospel and the world, for its function is to be a vehicle whereby the gospel is transmitted to particular cultures. But just as there is a tension between the world and the gospel so there is at times a tension between the Church and the gospel. Although it is an inspired institution, the Church does not always perfectly reflect the gospel (as it did, for example, in the time of Enoch) simply because those of us who constitute the Church do not fully live the gospel. The Church is a mirror of our collective attempt to follow the teachings of Christ.

Those who do not understand this have difficulty when the gospel and the Church come into conflict, as they sometimes do; such persons either abandon the Church for the gospel or abandon the gospel for the Church. The challenge of true discipleship, however, is to live the gospel in the world and in the Church, to be witnesses of Christ “at all times, and in all things, and in all places that ye may be in” (Mosiah 18:9).

By keeping the gospel’s perspective clear we may be able to transcend the limitations of our respective cultures and more completely fulfill our destiny, as individuals and as a Church. As John Sorenson concludes: “When the time comes that Mormons in the central homeland come to the realization that they too are constrained by cultural ways which have nothing directly to do with the gospel they espouse, the result could be a kind of Copernican revolution with attendant new insights into the Church and the scriptures and the meaning of life.”

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue