Articles/Essays – Volume 35, No. 4

Where the Walls of the World Wear Thin | Judith Freeman, Red Water

As Red Water opens, John D. Lee, an adopted son of Brigham Young, a member of the Council of Fifty, a leader in the Host of Israel (the private militia formed by General Joseph Smith), is being put to death by a firing squad. “‘Center my heart, boys. Don’t mangle my limbs.’ Five shots rang out, and then another five coming so close together they sounded like one slightly drawn-out explosion. He fell back on his coffin, dead” (p. 5). It is a nineteenth-century, classically somber scene, with both winter and spring hovering in the wind that never stops blowing.

Inspired by the writings of the late Juanita Brooks and her own rich imagination, author Judith Freeman has produced a fascinating account of three of the nineteen wives of the infamous John D. Lee: Emma Batchelor Lee, Ann Gordge Lee, and Rachel Woolsey Lee. Though this book is a novel, the work is based on extensive research in journals, letters, and pa pers from Special Collections of the J. Willard Marriott Library and the American West Center at the University of Utah, the Huntington Library, the Utah Historical Society, and private collections. With a strong feel for the harsh landscape of southern Utah, the demands of colonial Mormonism, and the challenge of being sister wives to such a controversial man, Freeman enters into territory where some writers might fear to tread.

In three sections entitled “Emma,” “Ann” and “Rachel,” Freeman essays what it must have been like to be one of three wives with different temperaments, dispositions, and ages, who found themselves situated among the Saints in a polygamous milieu in the rough and tumble frontier society of pre-statehood Utah. All in the face of dishonor. As the settings shift from Harmony, to Corinne, to Kanarra, to Lee’s Ferry and Moenabba in the Ari zona Territory, Freeman examines the sacred and profane aspects of these women, their hearts and minds, their loyalties and the why of their loyalties, their spirituality, their sexuality, and the headstrong nature and willfulness of some, the straight-line obedience of others. All of this is rendered against the uncertain backdrop of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, each of the wives pinned to this moment in history, her life ultimately tainted by the blood that flowed there.

The character of Emma seems to fascinate Freeman more than that of the other wives, though much of the history of Lee and his family is explored in this section (Emma’s account takes up nearly half the book, approximately 150 pages of 321). As she reminisces from her lonely place in Lonely Dell (Lee’s Ferry) where she can always hear the roar of the Colorado River and smell the musky odor of arrowweeds and willows and clay mud, Emma accounts for the wives who’ve come and gone, the genealogy and psychology of the family structure, and the heavily-laden question in the minds of the wives about who was re sponsible for the Mountain Meadows Massacre. How did this all fit into their belief in the Gospel and the Holy Doctrine of Plurality of Wives? How did this affect their loyalty? Their sense of themselves? In this novel, Emma seems to be the most sensible, clear headed, and objective of these wives and the one to emerge with the least scarred sense of self. When Lee could not be present for the birth of her last son, she delivered “my own child with my son there to help me and I never thought of holding it against him” (p. 19).

Very little actual research material is available on Ann Gordge, and the story of “Ann” feels to be written more from the imagination than the others. After Lee has died and Ann has left the fold, Freeman opens the section on Ann as she rides “hunched up against the wind, letting her feet dangle loose from the stirrups, her eyes half shut against the billowing dust” (p. 171). She’s traveling through stern country dressed as a man and riding a horse in a north/south/up-and-down-the-territory search for her stolen gray mare Vittick, the “finest-blooded horse she had ever owned, and due to foal soon” (p. 173). This situation ups the ante on the dramatic curve of this section’s plot. Freeman has a fine sense of horses and horsemanship, as well as for the physical territory Ann rides while trying to recapture her horse.

Ann has always been a natural woman who is sure of her sexuality and Lee’s attraction to her, even at the age of thirteen when he first noticed her and took her for a wife. But apparently she never wanted to be a mother, let alone the mother of the three children she bore Lee. Before his execution, Ann had decided not to join Emma and Lee on the Colorado River (p. 165), leaving two of her children, Sam and Belle, with Emma and her youngest son, Albert, with her brother for safekeeping. But nothing being as simple as it seems, the reader is shown the vulnerable side of the independent Ann. She pauses in the midst of her search for Vittick to stand for a long while above the ranch of her childhood where her brother now lives. She watches Albert crossing the barnyard in weak morning light and considers “the possibility of walking down the hill and surprising them all.” But, ultimately, she can’t imagine the moment of parting. “She could not see how she might take leave of the boy again, or what she would say to her brother if he asked why she did not take her son with her now” (pp. 243, 244).

The final section about Rachel (called “The Mouse” by her sister wives) is rendered in quotations from her journal. Whether these are real or imagined, Freeman doesn’t say, but most likely they are a combination of both. The quotations are terse, and Rachel comes across as a woman who won’t indulge her emotions or her fears. Straight ahead seems to be her course. No flinching. After all, she’s the most devoted of Lee’s wives until the bitter end. (Of note is the fact that Rachel’s sister, Aggatha, had been Lee’s first wife, her youngest sister, Emoline, was the eleventh wife, and he’d also married their widowed mother, Abbagail, at the age of sixty “for her soul’s sake” (p. 45). There were four Woolsey women in the cast of Lee’s wives.) However, in a telling moment, Rachel experiences an uncommon vulnerability when she realizes she’s never been loved in the self-less way that Emma and Ann love each other, not even by her own sister Aggatha, whom she’s idealized and from whom she’d never received such affec tion. In the final section, which be longs to Rachel, Emma returns to Harmony after Lee’s death to reclaim Ann’s daughter, Belle, who’s been “on loan” to Rachel. Emma, who had nursed Belle from the time she was born and whose intentions are to raise the girl as her mother would have wanted, is told she cannot have the girl. In a display of complex human emotion, Rachel justifies her actions by thanking the Lord above that “at least two of her (Ann’s) children have been spared a life with such a creature for a mother. She is not only a fool but a liar and I expect she’ll come to a bad end” (p. 319).

The central question of the text seems to be the culpability of John D. Lee in the Mountain Meadows Massacre and how that cancerous unknown affected these three women. Was Lee, whom his wives addressed as “Father,” a fine man, honorable at every stage of the game? Was he a complicated man who might use his power or position unethically? Was Lee (who in real life was posthumously restored to church member ship in 1961) a scapegoat for the Brethren? Other questions spin out from there: were the wives treated fairly in this polygamous situation? Were the wives honored enough or was it more important for each of them to lay down her questioning and individual impulses in the service of God’s Kingdom and the Principle? Can any human live the Principle in all fair ness? What of the individual in the tide of the collective?

The finest offering of this novel is Freeman’s compassion for each of these wives and her understanding of the complexities of human nature in the face of an absolute which does not prove to be an absolute after all. In this text, questions of the how and the why of the Massacre, the innocence or guilt of John D. Lee, remain open. But the feeling remains that there were many people caught in the web of their self righteousness who could not allow for the truth of the matter to emerge.

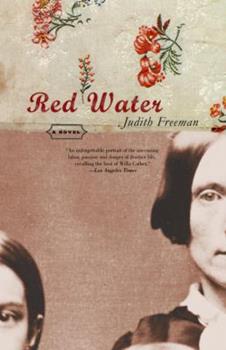

Red Water, by Judith Freeman (New York: Pantheon Books, 2002), 321 pp.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue