Articles/Essays – Volume 04, No. 4

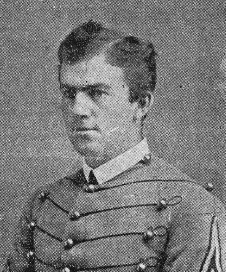

Willard Young: The Prophet’s Son at West Point

A common object of humor among visitors to Mormon Country in the nineteenth century was the large number of children. Many travellers’ accounts contain a version of the story of Brigham Young’s encounter with a ragged street urchin:

“Who’s child are you, Sonny?”

“I’m Brigham Young’s little boy. Please sir, do you know where I can find him?”[1]

In her portrait of her father, Susa Young Gates denies this view, stating that the relationship of Brigham Young to each of his fifty-six children was both intimate and affectionate.[2] This, despite his heavy responsibilities in connection with the political, economic, and religious affairs of the Church and territory. A study of the correspondence of Brigham Young with one of his children, Willard Young, confirms this view, and reveals, in addition, hat the President was not only a master colonizer, but also a master letter writer. The career of Willard Young also demonstrates the potential leader ship among the young people reared in the Church in Utah Territory in the last half of the nineteenth century.[3]

Willard Young was born in Salt Lake City on April 30, 1852. He was the third child (and only son) of Clarissa Ross Young, and the thirtieth child of Brigham Young. His mother died when he was but six years of age, so he was reared by his “aunties” in the large Brigham Young household in the Lion House. His independent spirit was exhibited as early as the age of thirteen. He and his half-brother Ernest had observed that their father believed in work as well as play, so they asked him if he would permit them to leave school and go to work. As told by his sister, Susa Young Gates:

Father told them they must go back and talk it over with their mothers and older sisters and then come to him. They returned with the desired consent and then father told them that he wanted them to stay by their decision; they could work a while and then go to school a while. He was quite willing that they should work for one r more years and then they would perhaps be willing to go to school and work hard at that. They went to work on the farm in teaming and woodhauling. After a year they were eager enough to get back in school.[4]

Apparently, Willard, at least, did “work hard” at school, for he was “the best scholar and strongest boy” at the Deseret University (forerunner of the University of Utah) in Salt Lake City.[5] When word was received from the Secretary of War in May, 1871, that a vacancy existed at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, and that William H. Hooper, Utah’s delegate to Congress, had the privilege of naming a candidate, President John R. Park of the university suggested Willard.[6] He had just turned nineteen. When Willard asked his father if he could accept the appointment, the Prophet replied: “I will let you go, but will send you as a missionary.” His name was then presented in the general priesthood meeting for a sustaining vote and his name was carried on the missionary list for the next twenty years.

Already an elder, having been ordained at the age of sixteen, Willard was set apart under the hands of the First Presidency to go to West Point, with the following blessing:

We set you apart to this mission and we seal this Priesthood upon you, even the Priesthood of the Most High, with the blessings pertaining thereunto, that you may go and fulfill this high and holy calling and gain this useful knowledge, and through the light of truth, make it subservient for the building up of the Kingdom of God.

President Young’s characteristic solicitude and fatherly advice are reflected in his first letter to Willard, dated May 19, 1871, shortly before his departure for New York:

In entering the Academy at West Point you are taking a step which may prove to you of incalculable advantage. You are thereby enjoying a privilege which falls to the lot of comparatively few. You will do well to treasure up the instruction so abundantly provided there, that in after years you may be prepared to take a place in the foremost ranks of the great men of the nation. Experience will teach you that the greatest success does not attend the over-studious, and a proper regard must be had to physical as well as to intellectual exercise, else the intellectual powers become impaired, and, therefore, bodily recreation and rest are as necessary, as they are beneficial to mental study.

Every facility will be afforded you at home by your friends, in the furtherance of your studies, and I have no doubt that a straight- forward, manly, upright course on your part, will gain you friends and ensure you valuable aid from your fellow students.

Bear in mind above all, the God whom we serve, let your prayers day and night ascend to him for light and intelligence, and let your daily walk and conversation be such, that when you shall have re- turned home, you can look back to the time passed at West Point and see no stain upon your character. You will doubtless have your trials and temptations, but if you will live near the Lord, you will hear the still, small voice whisper to you even in the moment of danger. Attend strictly to your own business, be kind and courteous to all, be sober and temperate in all your habits, shun the society of the unvirtuous and the intemperate, and should any person ask you to drink intoxicating liquor of any kind, except in sickness, never accept it. Select your own company rather than have others select yours.

If at any time you feel overtaxed or homesick, seek relaxation in the Society of our Elders in New York, or in other places where they may be travelling, that is, when the rules of the Institution or special license, permit you leave of absence.

Write to me frequently, and any assistance you need, that I can furnish, will be provided. May God bless you and preserve you from every snare and give you His Holy Spirit to light your path before you, and help qualify you for usefulness in His Kingdom.

Your affectionate father,

Brigham Young

Willard’s tour of duty at West Point enables us to observe the adapt ability of young “pioneer” Latter-day Saints for this kind of training. As the first native Utahn to enter West Point, he attracted nation-wide attention. This was particularly true because his father was an almost mythical symbol of qualities both good and bad. In his class of “plebes” was also the first Negro appointed to West Point; so the New York (and other) newspapers featured these facts in sensational articles for several weeks. An interviewing columnist for the New York Herald described him as “a fine, manly looking fellow, robust and tall, and, taken altogether, the best looking man physically among the greenies . . . frank in speech.” He had, wrote the reporter, “conducted himself in such a straightforward way that he has already made no small number of friends among the cadets.” When the re porter asked him what he would do about going to church, he replied good humoredly:

I will do the best I can. It makes no difference to me what church I go to so long as I do what is right. The fact is the Mormon principle is that there is good to be found in every church, but we believe that we have in our church all that is good.

The correspondent concluded:

My opinion of him is that he ought to pass. He would make a splendid officer. Some of the cadets laugh at him because he won’t smoke, and he complains of having heard more hard swearing since he came to West Point than he ever heard in his life before. But he has such extraordinary notions—extraordinary in a West Point view—of what a good man should be, that I think he would make a capital anti-swearing missionary, if not a capital officer. . . . [H]e is a capital fellow, . . . and is, to all appearances, “a man for a’ that.”[7]

In his second letter, dated June 17, 1871, President Young comments on some of this “newspaper talk.”

We were all well pleased to hear from you, and to know that you passed a successful examination. This news was considered of sufficient importance to be flashed across the wires with the general telegraphic dispatches. . . .

It appears from some of the eastern papers, they are rather exercised over your admission among the cadets & one correspondent writing from this City to the N.Y. Herald, wants to know, “Will the boys permit the outrage;” it is easy to guess the source whence this emanated, some member of the notorious ring here, who leave no stone unturned to create friction between us and the Government. You are aware how signally they have failed and this malicious though very paltry effort only serves to show them up as they are. . . .

We are having a novelty in the shape of a Methodist camp meeting located on the Orson Spencer lot just across the street north of Henry Lawrence’s house. Meeting is held in an extraordinarily large tent said to accommodate 3000 persons. I am not aware they have made any converts as yet, though a large number of our people at- tend nightly. We have advised all to attend, young and old. I have only been present at one meeting. The affair is very dry. Mr. [W. H.] Boole who preached on that occasion put me in mind of an old, dried up wooden pump, laboring and creaking in a dry well, working very hard but producing no water. I understand their services will close tomorrow.[8]

Though you are absent from us and far from home and your dearest friends, be assured we are not unmindful of you, our prayers are constantly exercised in your behalf that you may be kept free from the contaminating influences that will doubtless surround you. Let me again advise you that you cannot be too careful to shun the temptations of the day. We are not afraid of you, but you are in a more conspicuous position, probably, than you realize; the eyes of many are upon you to see what is likely to be your future. You will meet with those of your companions who will try every means to induce you to deviate from the path of virtue, but with a firm front, you can easily parry every such effort and still be kind and courteous, and rest assured that this course will win for you far greater respect, even from the unvirtuous, than that which would follow, were you to fall in with the dissolute habits of the day.

Above all things, seek closely to the Lord. Pray for His Holy Spirit to guide your steps and to deliver you from every snare.

Write to us often, and at length; your letters will be looked for with pleasure. . . . When you write I would like to learn in detail the routine of your daily life, and what your studies will consist of. Whether your friends are allowed to visit you, & if so, are they restricted to certain times? Indeed, a brief description of the entire rules of the Academy would be quite interesting to us, and might furnish an interesting article for the News.

P. S. I am particularly desirous to know the regulations about visitors, because, if allowed, I shall request all our elders visiting in your neighbourhood to call upon you. . . .

At West Point the regulations required the cadets to attend chapel serv ices unless the parents had religious scruples against them doing so. As indicated in his interview with the reporter for the New York Herald, Willard had no reservations, but thought he should write to his father to see what he thought about it. He received an answer, dated July 25, 1871:

We would like to learn in detail the routine of your daily life; what your duties and exercises consist of; what the regulations are about visitors; whether ladies have access to the cadets & under what restrictions, if any. This last is a matter I am quite concerned to know about, as I understand you cadets are exceedingly popular with the fair sex & some of them are very, very dangerous when so dis- posed, just for the sake of having a laugh at their victims; shun such as you would the very gates of hell! They are the enemy’s strongest tools, & should be resisted as strongly. Beware of them! . . .

The Bishop [John Sharp, who had visited Willard during a trip East on business connected with the Union Pacific Railroad] tells me, you are kept so busy, that you have barely time to attend to your correspondence. All who have written to, or spoken with me are well satisfied with your course, so far, and the Bishop assures me that whatever may have been the feelings of the cadets toward you at first, you are now looked upon by them as “a pretty good fellow.” I will go still further with this, and say that we hope yet to see you set a pattern for all of them. By exhibiting your character, & the principles you profess, in your daily walk and conversation, and by refraining from every appearance of evil, you will not only be admired by the good and the upright, but you will command that respect, that even the most unvirtuous are willing to accord to those who truly deserve it. There is no question but that you can do a great deal of good among your fellow students and we hope to see you accomplish it. No matter what the world at large believe, or say about the Latter- day Saints, if we do our duty, and live for it, we will be found, among the children of men, at the head, & not at the tail.

With regard to your attending Protestant Episcopal service, I have no objections whatever. On the contrary, I would like to have you attend, and see what they can teach you about God and Godliness more than you have already been taught. When the Methodist big tent was here I advised old and young to attend their meetings, for that very reason, but I was well satisfied it would not take our people long to learn what the Methodists could teach them, more than they had already been taught. . . .

In another letter, dated February 17, 1876, President Young had this to say:

I am desirous that you should use the golden time, now upon your hands, to the very best advantage. It may be that you will never have such another opportunity amidst the care and bustle of after life as you now possess. Two things I am very anxious all my sons should be, faithful servants of our Heavenly Father, and useful members in his Kingdom. Integrity to the truth and ability to do good are qualities which I hope will characterize you all. And I will ac- knowledge that I have much happiness in the thought of how well my boys are doing at the present time. . . .

It must be very encouraging and pleasing to you in your thoughts of home, to realize the present activity in the works and feelings of the Saints whilst the progress of the work of God is made manifest in so many quarters. From every point we receive encouraging news from our missionaries out in the field and baptisms are not un- frequent. . . . When we think of the vast amount of preaching our elders are doing far and wide out in the world, the spirit of reformation amongst gathered Israel, the work of the Father commenced amongst the degraded children of Lehi, and the spreading out and strengthening of the settlements of the Saints, we cannot come to any other conclusion than “Zion is growing”, nor refrain from praising our God for his manifest and repeated preservation of his people from the evils the enemies of righteousness seek to bring upon them. . . .

Such was the encouragement and advice of an indulgent and interested father. At the end of his first year Willard stood second in his class in mathematics, but thirty-second in French, and in general standing, seventh. His progress continued good during the years that followed, and he graduated with the class of 1875. For the four years, out of forty-three students in his class, he ranked second in discipline, fifth in engineering, sixth in ordnance and gunnery, eighth in mineralogy and geology, and fifteenth in law. In general standing, he was fourth in his class.[9]

Upon graduation he was commissioned 2nd Lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers—one of four in his class receiving this appointment. He first served with the School of Engineers at Willitts Point (1875-1877), then on the Wheeler Survey in Idaho, Utah, Nevada, and California (1877-1879). For a four-year period (1879-1883) he served as assistant professor of civil and military engineering at West Point; the student of whom he was proudest was General George W. Goethals, who later achieved fame when he directed the construction of the Panama Canal. While at West Point he courted and married Harriet Hooper, daughter of the Congressional Delegate who had appointed him to the Academy. Harriet is described as having been “really beautiful, graceful, and cultured, as measured by the highest standards of New England’s social ‘400.’ ” The marriage seems to have been a completely happy one. To their union were born five daughters and one son, of whom three daughters and the son survived childhood.

After his tour at West Point, Willard was appointed to take charge of the Cascade Canal and Locks, Oregon (1883-1887). The construction of these works made possible the navigation of the Columbia River throughout its 230-mile length.[10] Upon completion of this assignment, Lieutenant Young then proceeded to Portland, Oregon, to take charge of the harbor works on the coast of Oregon for the years 1887-1889. His next assignment was in Memphis, Tennessee, in connection with construction on the Mississippi River (1889-1891).

While Willard, now a captain, was at Memphis, the First Presidency of the Church (Wilford Woodruff, George Q. Cannon, Joseph F. Smith) was arranging for the establishment of new academies and colleges which would provide additional secondary and advanced training for Latter-day Saint youth. Brigham Young, before his death, had deeded properties in Cache Valley for the establishment of the Brigham Young College at Logan, and in Utah Valley for the founding of the Brigham Young Academy at Provo. The President was in the process of establishing a similar college in Salt Lake City at the time of his death in 1877. After various legal complications in the settlement of his will had been overcome, the Young family, in 1890, agreed to donate to the Church properties on which to erect and maintain a college in Salt Lake City equivalent to the Brigham Young College and Brigham Young Academy. The First Presidency thought Willard was the best-equipped man to direct the contemplated college; early in 1891 they asked him to resign his Army commission and return to Salt Lake City to become the school’s first principal. Captain Young replied to them, under date of May 6, 1890, as follows:

I shall be very glad to resign from the Army to assume the duties mentioned . . . . Both my wife and myself are pleased at the thought of going back to Salt Lake to live, as no other place ever has, nor, I believe, ever can seem like home to us. We are both very much gratified at the confidence that the call to such a position implies.

He served as the founding principal of what became known as Young University during the years 1891 to 1893. He later served as City Engineer of Salt Lake City (1893-1895); Assistant Chief Engineer, Pioneer Power Company (a Church enterprise), 1895-1896; and as the first State Engineer of Utah, 1897-1898. He was also the first Adjutant General of Utah and first commanding Brigadier General of the Utah National Guard.

In 1898 America declared war on Spain. Many had expected that the Mormons would “sit this one out,” as had been the case during the War Between the States. Although Utah had been granted statehood, her elected representative to Congress, Brigham H. Roberts, was denied a seat because he had been married (before the Manifesto of 1890) to more than one wife.[11] Anti-Mormon sentiment still was rampant throughout the nation (seven million people had signed the petition against the seating of Roberts). Nevertheless, it was President Woodruff’s advice that the Saints demonstrate their patriotism by assisting with the war effort. At his suggestion, an editorial was published in the Deseret News, urging young Mormons to “do their full and valiant duty” in responding to the nation’s call to arms.[12] One of the first to volunteer—indeed, one of those who urged President Woodruff to encourage all young male Latter-day Saints to volunteer—was Willard Young. Described as a “very magnetic person and entertaining conversationalist,”[13] Major Young was appointed colonel of the Second Regiment of U.S. Volun teer Engineers, and served in that capacity from May 1898 to May 1899. Upon his release he was commended by President William McKinley for valiant service in connection with the provision of sanitary works in Cuba.[14]

At the end of the war, Colonel Young went to New York City as general manager, and later president, of the National Contracting Company (1899—1902). During these years he supervised the construction of some of the works of the Niagara Falls Power Company; the main drainage works of the city of New Orleans; several sections of tunnels for the Boston Subway; a sewer system for Boston; and a dam for the Hudson River Power Company, near Glen Falls, New York. He continued in private engineering practice from 1902 to 1906.

During these years in New York City, Colonel Young and his wife used the rather considerable property which Harriet inherited from her father to send their children to the best schools. Their son, Sidney, went to West Point, while their three daughters, Hattie, Claire, and Alice, were enrolled in Vassar. Nevertheless, father and mother saw to it that the children attended Sunday School and Sacrament meeting. The only available service in New York was conducted in Brooklyn by missionaries. To reach it the six Youngs, who lived in a fashionable home on West 81st Street, had to rise early, take a half-hour streetcar ride to the East River, change to a ferry boat to cross the river, then take another car ride for another mile or so. At the meetings, they found two to four elders and about a dozen members. This required thirty-six nickels for fares, but their greatest joy came from inviting the elders to return with them for Sunday dinner. Diary entries show that they “made it to meeting” virtually every Sunday. Clearly, this metropolitan engineer and Mrs. Young honored their heritage and the religious system which their fathers had been instruments in establishing.

In 1906 Colonel Young was called once more by the First Presidency of the Church—this time to become the President of the Latter-day Saints University in Salt Lake City.[15] He served nine years in this capacity (1906- 1915), after which he acted as counselor to the president of the Logan Temple.

Upon America’s entry into World War I in 1917, President Young, although past retirement age, once more volunteered for Army service. He was appointed United States Agent in charge of all Army engineering work on the Missouri River, serving from 1917-1919.

At the close of the war, the Colonel returned to Salt Lake City and served for the remainder of his life as Superintendent of Church Building Construction. He was likewise a member of the Church Board of Education, and of the Ensign Stake High Council. He died in Salt Lake City in 1936, at the age of 84.[16] At the time he was the oldest living son of Brigham Young.

As the first native Utahn to become an important officer in the Army, and the first to attain national eminence as an engineer and educator, Colonel Young helped to establish the heritage of achievement, of broad and helpful service, and of honor and faithfulness that Latter-day Saints seek to emulate.

[1] Or, as Artemus Ward put it: “He sez about every child he meats call him Pa, & he takes it for grantid it is so.” Artemus Ward, His Book (New York, 1865), p. 83.

[2] Susa Young Gates, in collaboration with Leah D. Widtsoe, The Life Story of Brigham Young (New York, 1931).

[3] In the Manuscript Section of the L.D.S. Church Historian’s Library and Archives, Salt Lake City, are located the papers and diaries of Willard Young. His “Name File” includes various letters written by President Brigham Young to Willard during the 1870’s, some of his addresses and sermons, and various biographical information compiled by the Assistant Church Historian, Andrew Jenson. His “Diary File” includes eleven diaries. Entries begin with September 15, 1877, and include entries for the years 1877, 1878, 1879, 1880, 1882, 1883, 1890, 1898, 1902, 1905, and 1906. These are primarily “professional diaries,” with notes on his various assignments and activities as an engineer. The present article is compiled from information in these two files, and from other sources as cited.

[4] The Life Story of Brigham Young, p. 347.

[5] Deseret Evening News, June 8, 1871.

[6] There is an 8-page typed statement about his call to West Point among the papers in the Willard Young “Name File.”

[7] Reprinted from the New York Herald in the Deseret Evening News, June 8, 1871. The same issue reported he had passed his exams.

[8] The Methodist revival was the first non-Mormon religious revival in Utah. Mention of the revival is found in Edward W. Tullidge, The History of Salt Lake City and Its Founders (Salt Lake City, 1886), p. 543; Orson F. Whitney, History of Utah (4 vols., Salt Lake City, 1892-1904), II, 823-824n; B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church . . . (6 vols., Salt Lake City, 1930), V, 495-496; and T. Edgar Lyon, “Evangelical Protestant Missionary Activities in Mormon Dominated Areas: 1865-1900” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Utah, 1962), pp. 150-151. From these sources we learn that Brigham Young publicly urged Latter-day Saints to attend the revival meetings and that several thousand did so. When one of the Methodist ministers—there were seven—expressed a wish to address the Sunday School children of Salt Lake City, Mormon leaders arranged for some 4,000 of them to at tend the evening of Sunday, June 4, in the Salt Lake Tabernacle. The Deseret News of June 19, 1871, stated that there was no indication of a single Latter-day Saint convert during the eight-day revival. The Salt Lake Tribune reported on June 15, 1871, that as the result of five days of meetings there had been “one professed conversion.”

[9] Letter of June 30, 1875, of “Ex-Army Officer,” in Deseret News, Journal History of the Church, this date. The Chicago Times is reported to have commented as follows on Willard Young’s graduation and high standing: “It has been said that polygamy results in the impairment of the mental faculties of the offspring, but this does not seem to prove the theory.” Journal History of the Church, July 2, 1875, p. 1.

[10] The Salt Lake Herald for July 12, 1885, has a long article on his work in Oregon.

[11] R. Davis Bitton, “The B. H. Roberts Case of 1898-1900,” Utah Historical Quarterly, XXV (January, 1957), 27-46.

[12] “No Disloyalty HereV’ Deseret News, April 25, 1898, and Journal History, this date.

[13] Deseret Evening News, March 11, 1898, quoting the Cheyenne, Wyoming, Sun-Leader.

[14] See “Sons of Utah Honored,” Deseret Evening News, June 4, 1898.

[15] On. April 4, 1892, Willard Young had asked the Saints assembled in general conference to approve a request to the First Presidency that they appoint a committee of five to consider a plan for founding a Church University. The motion was seconded by Elder Francis M. Lyman and carried unanimously. The committee consisted of Willard Young, Karl G. Maeser, James E. Talmage, James Sharp, and Benjamin Cluff. The following day this committee recommended the establishing of “an institution of learning of high grade” to be known as the “Church University.” Upon a motion by Elder B. H. Roberts, the motion was carried unanimously. Previously there had existed an L.D.S. College and the infant “Young University” which Willard Young had directed. After one year of operation (1893- 1894) the “Church University” was discontinued and the Church threw its support to the University of Utah. The former institution then became known as the Latter-day Saints College. In addition to various high school and vocational courses, the faculty taught college-level courses in religion. In a sense, the L.D.S. College in Salt Lake City functioned as a kind of L.D.S. Institute of Religion for students at the University of Utah. In 1930, most of the departments were discontinued and the institution became the L.D.S. Business College.

[16] Obituaries of Willard Young are found in: Salt Lake Tribune, July 26, 1936; Salt Lake Telegram, July 27, 1936; The Deseret News, July 28, 1936.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue