Articles/Essays – Volume 40, No. 2

Once upon July

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

What hue lies in the slit of anger

ample and pure as night

what color the channel

blood comes through?

—Audre Lord

At home it was hot . . . days and days above a hundred. I could imagine the leaves of summer wilting in the afternoon heat. But that was so far away on the other side of the equator.

Here it was cold. Although it was July, I had on my parka and a sweater as I walked down a rough, cobble-stoned street shaded by two-story, pastel-colored adobe walls. I listened to the sibilant clipping of Bolivian Spanish and the soft guttural rattle of Aymara as people negotiated prices and shared gossip in the small stores whose light rushed out, like warmth, into the narrow street.

It was July 1994. My teaching duties had finished at Brigham Young University; and come that fall, I would work at Colorado College. My mother’s health was improving, and I felt I could go to Bolivia. I was staying in an inexpensive hotel, in a cold, narrow room. Instead of a window it had curtained, glass doors that opened onto a second-floor balcony above the street by the market. It was noisy and had a lumpy, uncomfortable bed, but it brought back memories. I had stayed here years ago when I came to this small, but important, town on Lake Titicaca to do field research. But I really wasn’t talking with anyone. I felt wilted, as if the water of my life had evaporated under a mean sun.

I was trying to write a book about Bolivia and Mormonism, the book I was given leave to write before BYU announced it would not retain me after my third-year review. My leave, though, had disappeared in writing a lengthy appeal of their decision in vain, in hoping futilely for reason and brotherhood in that process, and in many nights on hospital couches, sometimes sleeping fitfully and sometimes praying desperately for my mother’s life to be spared.

I felt I had withered to a faint, green speck, the size of a period. At night, every night, I relived the harsh words spoken and written about me at the university and my anguish about my mother who wanted so badly to live that she let them slice her stomach in three sections to peel it back, remove her wilted liver and connect over hours and hours of painstaking surgery a new one from someone else’s tragedy. When I wakened, I ached. I did not have a firm hold on who I was, but I knew there had been a long, leafy sentence before the period I now had become.

Somewhere, I suppose, I knew it was really a semicolon with more to come. But I felt small, fetal, and closed at the end of an existence that somehow kept gracelessly slipping past the period’s guard.

As I wandered around town like some silent wraith, I could feel the cobbles through the soles of my shoes, as if I walked only on periods and couldn’t even wish for commas, colons, or question marks.

I had first come to this town almost twenty years before on a P-day excursion with my district of missionaries. I remembered my awe at this hamlet watched over by an old, elaborate, Moorish basilica in honor of the Virgin of Copacabana. She was named after the town. But the sur rounding terraced hills and the deep blue lake whose distant shore I could not see dwarfed her massive church. I had been back many times as an anthropologist and had lived there for some months nine years before while doing fieldwork.

Then I was a Latter-day Saint, nursed with faith and swaddled with identity. Now I did not feel I was anyone. I had become used to nightmares at night and silence, emptiness, and solitude during the day.

***

A year before, on a June evening in 1993, I awaited the much-belated results of my third-year review from BYU. I knew what was coming, but I hoped I was wrong. I waited and waited, anxiety surging through my veins.

To survive the wait on that June evening, I threw myself over and over into the sultry melody, filled with saudades, of Heitor Villalobos’s Bachianas Brasileras Number 5. Whether in the cellos or the wordless soprano, I, too, would sway soulfully in the delicious presence of absence de scribed by that Portuguese word that cannot find a mate in English. The music reminded me of other cultures, other worlds, other ways of being, and other feelings as I waited.

Around 2:00 A.M. on that sultry summer’s night, the chair of the anthropology department, John Hawkins, his face sharpened by tension and his voice weakened with grief, walked through my apartment’s open door with a letter from the university retention and tenure committee. He read the letter to me, his voice conveying a sense of almost disbelief. In his decades at BYU, he had never heard of the university firing people at third-year review. He was in shock. He had not believed me when I predicted this would happen. Oddly, I felt a strange calm, perhaps still from the music, and perhaps from finally reaching what I had felt for several months was likely to happen.

We discussed strategy, and he expressed his loyalty and support, although I know that I was difficult for him. He had struggled to find ways to mentor me and to rein in what he saw as self-destructive, or perhaps just quixotic, tendencies. He had warned me not to report, in an article on Mormon masculinity, what I had been told about the Church Office Building being a phallic symbol, but his warning didn’t make sense to me. John felt people might be deeply offended by comparing a symbol of something sacred to them, the Church, to genitalia, despite the rich Freudian associations. Yet to me, it all seemed so obvious and so ho-hum. But he was right. That image, and indeed the article, threatened many people, as did my research on the guerrilla movements that were targeting the Church in South America with bombings and missionary assassinations.

At the long table where the university’s vice presidents heard my second appeal during the fall of 1993, BYU President Rex Lee slyly argued that, while the image was not legally obscene, it felt so in the context of Mormonism. He challenged my use of Freud, whose thought he felt was much discredited and had no place in the academy. One of the vice presidents insisted over and over that by using Freud I had done something unacceptable in the academy.

Then it was my turn to be in shock. I felt as if I had moved into a world where everything was not what I had always assumed it was. White was gray and red was orange. Freud was taboo. What the guerrillas had said about Mormons was interpreted as my words. I was made out to be a bad anthropologist who just wrote personal essays; but as they also seemed to suggest, I was such a good anthropologist that I had quit being a Mormon, since I was guided more by anthropology, they felt, than the gospel. I suffered from a peasant-centered view that mangled my science, yet I wrote such interesting essays that the accuser hoped I would stay at the university, even though it seemed to me he was doing everything to keep me from staying.

John had warned me, but I had not understood and instead had published that evidently offensive image and had spoken many other things that evidently offended many men at BYU. I still could not believe how strongly offense was taken.

Another time John and I were sitting on the lawn outside the Harris Fine Arts Center, after listening to Elders Neal A. Maxwell and Henry B. Eyring deliver diatribes against critical theory and so-called postmodernism, because of challenges these bodies of thought made to authority. As we sat there, against a background of passing legs, John shifted the subject and said, “David, you wouldn’t be in trouble if you only dressed differently.” I did not know that there was a dress code that disapproved of how I was dressed—in sandals, jeans and a bright-colored shirt. At most universities I would have been almost conservative in my dress. Another BYU anthropologist sent the message through his son that I was a good ethnographer and that, as a result, he could not understand why I had not figured out how the system worked. But, as I asked John, bewildered, “Why didn’t you tell me there was an unwritten dress code? I didn’t attend this university as a student, so came to it unaware of its culture.”

John, in his dress slacks, light pastel shirt, tie, and spit-shined shoes, struggled to understand me. He had gone out of his way to recruit me, treated me as a younger brother, and, uncomfortably, sat beside me when the representative of the university committee rejected his arguments on my behalf, refused his observations of procedural irregularities, and attacked the department’s integrity and quality. The committee claimed that John had provided the dagger with which they slaughtered my record. He was hurt because he had never intended such an effect.

A little over a month later, in November 1994, John left his classes to sit with me all day in the LDS Hospital waiting room while the surgeons struggled, hour after hour, to give my mother a new liver, despite the shriveling of a critical artery or vein needed for that vascularly rich organ. He brought me food.

Alan Wilkins, who had been appointed associate academic vice president in the fall of 1993, if I remember correctly, and President Rex Lee both called the intensive care waiting room while we struggled with fear and anxiety, to express support and to tell me my mother was in their prayers. As I stood in the harsh light of the reflectively waxed hospital hall and people pushed past my huddled back, they also asked permission to speak with my stake president about my personal worthiness. I interpreted this as a trap. It made their well-wishing cruel. I refused to give up my legally sanctioned priest-penitent privilege because I thought it a bad precedent but gave them permission to ask me the temple recommend questions, if they were worried about my worthiness. They did not call back.

I was furious that they tried to use my time of anguish to persuade me to give up that important privilege, thinking they might have found an ecclesiastical loophole that would release them from ruling on my appeal. They spoke with kindness and solicitousness, but to me their purpose seemed vile.

After two very long operations over two consecutive days, the surgeons told my siblings and me that they had done their best but that there were complications. They did not know if the transplant was a success.

We were allowed, from time to time, in the shock trauma intensive care room where they were caring for my mother. She seemed a pale, haunted cyborg with all the machines attached to her, larger tubes down her throat, and smaller tubes draining various wounds in her abdomen. She oozed blood through those smaller tubes; and minute by minute, still smaller tubes dripped a constant supply of new blood into her veins.

She wanted to live. Twenty years previously she had received an unknown disease, later called hepatitis-C, from just such a bag of blood. Year after year she had less energy and had more trouble concentrating as her skin yellowed and physicians struggled to understand why her liver was scarred when she never drank alcohol and had no history of hepatitis. Yet she wanted to enjoy her grandchildren, perform on the organ, and continue her research. She wanted to return to her parents’ homelands in Friesland and Yorkshire again.

I had accepted the job at BYU in 1990, despite serious misgivings and concerns, because I needed to be by her side and my father’s side as she fought. After my first four months, in early 1991, my father died of a sudden heart attack. Grief devastated my mother. As she weakened and required more constant care, the “Council of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve” issued its “Statement on Symposia,”4 and my stake president, Kerry Heinz, took a sudden interest in my writings and speeches. My mother said, “Son, I trust you will listen to the Lord. I believe in you, but I cannot pay attention. I have to devote all my energies to fighting for my life.”

During the intervening years, my sister-in-law and I had to make her meals, even though her sense of taste was troubled and her dietary requirements ever more exacting. Nothing was ever good enough. She watched and recorded all the cooking shows and assiduously collected recipes for us to try. She had constant appointments with a host of medical specialists as they drew ever more blood until her arms were mottled black, brown, and purple. One day a doctor said, “Too bad you’re in your mid-sixties; otherwise you would be a good candidate for a transplant.” We were shocked, because we had been led to believe that a transplant was, in fact, the goal, that we were struggling to keep her in good health while waiting for a liver to become available. But she had never been placed on the list.

We hustled. We found the right doctors and got her on the list, requiring ever more visits to another host of specialists and meetings with successful liver recipients. Around this time John made his night-time visit to my apartment with the fateful letter, and President Heinz called me in one last time. He had a pile of selections from my writings and partial transcripts of my talks with phrases highlighted in florescent yellow by, presumably, some unknown Church bureaucrat, along with the full texts I had provided him. After a long and difficult conversation, he said, “David, this may cost me my Church career, but I can find no reason to hold a court on you. I am washing my hands of this situation.”

For almost two years before this, 1991–93, he would call me in every few months to speak with me about something I was reputed to have said or written. Sometimes our conversations were angry. Often they involved long questions and disagreements as well as attempts at understanding, but always they were difficult and tense.

He had not known me before being instructed to call me in. As a result he spoke with my bishop to try to understand me. Richard Lambert was my bishop. An attorney and distant relative of mine, he also claimed friendship with Michael Quinn, who had been forced out of BYU in January 1988. Bishop Lambert always expressed interest, support, and love. During one long conversation in his office, we were talking about the difficulties of being single and thirty-something in the Church. Somehow the conversation turned to God, and I started to cry. I could not believe the tears that flowed down my face nor the sobs that shook my chest, since I cried only in private. But I was crying in front of him, because of his care, because I trusted him, and because everything was so very hard.

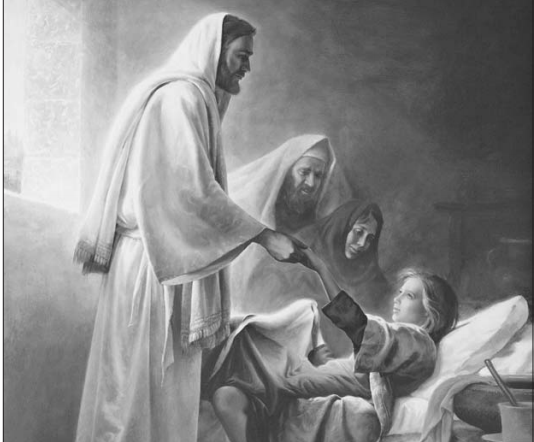

He asked if he could give me a blessing. As he placed his hands on my head, I continued to weep. He gave a long blessing that opened me and let me know that God loved me and that I had favor in his sight. Big, heavy tears poured down my cheeks, darkening the front of my shirt.

***

While my mother was still in the hospital during the fall of 1993, slowly gaining strength and color, my aunts and my two brothers insisted I keep my reservation to go to the national anthropology meetings in Washington, D.C. I did not want to go. I wanted to be at the hospital, to watch and help. They insisted. I booked my flight.

When in Washington, the American Anthropological Association meets at the Hilton off Connecticut Avenue. I sat in the entrance watching people swirl around, leadenly talking to those I knew. Inside I was at the hospital. My confidence in myself as a scholar and anthropologist was slipping. The phrases used to attack me and my scholarship echoed insistently. I wrote only I-centered essays. I did not do research. Anthropologists would dismiss my work as unworthy. My mind muted the myriad voices of support, acceptance, and approval.

I could not stand to be in the building and walked down Connecticut Avenue and across the bridge over Rock Creek to go to another hotel where the American Academy of Religion, I believe, was meeting. The street was icy, and it was bitingly cold. But the sharpness of the air as it stung my cheeks felt good against the overwhelming hurt inside.

I roamed around the book exhibits and sat for awhile in that hotel before deciding to return to the Hilton. As I crossed the bridge over Rock Creek’s deep chasm, a strong feeling imposed itself on me. Jump. Jump. It will be over. Jump.

It frightened me. I did not have the confidence that I could resist it. I was so afraid of walking near the edge that I walked down the middle of the bridge, in the road, frightening the drivers. But I could not trust myself near the sharp, icy edge.

***

When I returned from Washington, my family insisted I fulfill a contract to spend three weeks in Colorado teaching a block class on world systems theory, since I was on leave from BYU. I went, but I did not want to be there either. I wanted to be at the hospital. In Colorado Springs, other than when I was teaching or prepping, I would sit in an armchair in the apartment provided by Colorado College and wait for it to become night so I could go to bed. Yet every night I had nightmares.

While I was sitting in that chair that cold and dark December of 1993, Alan Wilkins called me. He apologized for not calling me earlier. He said that the decision of the BYU vice presidents regarding my appeal had already been released to the press but that I should have received it first. He said they had turned down my appeal. I was effectively fired.

I asked when the university would give me a copy of its reasoned responses to the issues in my appeal. He said no such thing would be forthcoming. I said, “That means, Alan, that you are firing me without letting me know why. When will I be informed as to the reasons for my firing?” He said they would not tell me. I pushed. He hesitantly admitted that the vice presidents had looked into the future and decided I would be a detriment to the Church and for that reason they were letting me go.

My head spun. “You mean you are firing me for something I haven’t even done?”

Alan, tall, thin, dark-haired and solicitous, known for his applications of anthropological theories of culture to understanding corporations, had entered my case when he was named associate academic vice president the year before. My relations with the administration prior to that had been difficult and conflicted. Alan brought a smoothness, an apparent concern for my well being, and an important civility into the process. He was so nice. It was seductive.

But in that niceness and solicitousness, I felt hurt. What the administration did struck me as nasty. It was hard-ball, vicious politics, in an ostensibly religious context of brotherhood. Alan’s kindness, ironically, made it hurt more.

When my block class ended, I drove back to Utah over the snowy Colorado Plateau and went to the hospital. Shortly before Christmas they released my mother.

***

When I awoke one morning in my Bolivian room, my breath was visible and winter’s chill had stiffened my joints. Frost feathered the glass panes of the doors as the first bus honked its horn in warning of its pre-dawn departure.

I dressed: long johns, pants, shirt, sweater, extra socks, gloves, parka, cap and a long scarf of alpaca wool wrapped round my neck. It was too cold to type. Unusually cold.

The stars of the Milky Way, like a flickering band of white, so wide it covered half the sky, still shone in the almost-dawn sky, challenging the town’s faltering lamps. Like a million cobbles, it paved a path from horizon to horizon. It was a thaki, a ñan, a road for souls to wander from death to life as it stretched from horizon to horizon. So many points. So many luminous bumps.

I sat on a rustic bench in the market huddled over a glass of hot api, a fruit-flavored, purple corn gruel. The air filled with the rush of kerosene flaming under huge kettles of api, coffee, and milk as the market women, made bulky under layers and layers of skirts, sweaters, and shawls, called out to each passerby and ladled many a cup of purchased warmth.

They say the dawn is dangerous. It is the coldest time of night, and it is humid. It is when it freezes the hardest, when frost is like a tangible being, falling from the night sky and haunting your every breath. I sat, staring into my api’s purple and white swirls while tearing at a piece of bread, as if I had no language, no way of sharing my thoughts with others. My thoughts were too much. They were the entire night’s sky that somehow would have needed to be stuffed into words and sentences. I could not do it. And so I sat, my hands slowly warming but my heart cold, listening as morning slowly came.

When the bells rang, calling people to first mass, I too got up, wrapped my scarf firmly about my neck and creakily made my way to the basilica gleaming white in the morning’s first sun. I sat on the hard pews, among a huddle of pilgrims and townsmen in the vast stretch of church, gold leaf, and colonial religious art. I looked up at the baroque, golden altar, an excess of movement and yellow light, at the dark Virgin, child in arms, among the panels and levels of a vertical spiritual world.

I listened to mass, standing and sitting, trying to repeat the prayers, “Padre nuestro que estás en los cielos, santificado sea tu nombre . . . ” the choir and organ sounding reedily behind me. This wasn’t my tradition, but I tried to participate and to feel the faith of the pilgrims. As we knelt, and around me they prayed, I felt their yearnings, their pain, their desires. My back tingled and tears moistened my eyes. I looked at the Virgin, but she seemed so distant, so loving for others. She wasn’t mine.

When mass ended, I walked down to the lakeshore around the intensely blue half-moon bay where umbrellas awaited visitors and tables stood empty. Boats, small wooden boats with outboard motors, were firing as they filled with passengers and headed into the seeming endlessness of the lake, a swelling, azure void.

***

The Christmas of 1993 was the last Christmas, but we had hoped it was the beginning of many. We gathered ’round the tree, my mother still with tubes in her arms, to watch my niece and nephews open gifts as they chattered and chirped with excitement. We all were surprised to find among the mound of presents gifts to each of us from my mother.

“But, Mom, you were in the hospital for almost two months. When did you shop?”

“I asked someone to buy them for me and have them wrapped.” My gift was a long, heavy box containing a baritone set of wind chimes tuned to a Javanese scale. I had stood in Shapiro’s a month or so before, sounding it softly, over and over, while my cousin shopped. Of all the wind chimes on display I liked that one the best. Its resonant notes had an almost transcendent sound, as if in their vibrations they could create a new world.

***

I used to carry a beeper and for months I lived, waiting for it to sound. All of us—my brothers, my mother, and I—had been given them, part of the waiting for the doctors to find my mother a liver. Every day she was weaker, her mind more fragile from the toxins. It was harder and harder to make food she would eat, much less like. I wore that beeper all through September of 1993 as, instead of writing my book, I labored over two hundred-plus pages responding to the ambiguous and inconsistent allegations of the university. I showed in great detail how they were not true, but how, even if they were true, they still had no standing in BYU’s regulations. I gathered hundreds of pages of supporting documents, creating a mass of more than a thousand pages. But the beeper did not sound.

I went to the appeal dressed in a suit and accompanied by John Hawkins, my department chair, to argue my case. I do not remember in much detail what happened other than sitting around a table with all those suit-clad, white men saying bad things about me and my record. It was solemn and decorous. The only woman present was a secretary scratching out a transcript to which I would never be allowed access.

We were sworn to confidentiality concerning the content of the meeting. They argued that this provision was for my protection, but I did not need that secrecy. I was willing to let the public into the hall. But they obliged me to agree. I had to accept the secrecy, since I hoped this would be a rational procedure and that they would rule on the facts. I had expended an extraordinary amount of time preparing to argue them.

Del Gardner presented the university’s case. An economist, he wrote an essay published shortly before the university’s hearing arguing that most of sociology and, therefore anthropology, was unacceptable social science because of roots in so-called conflict theory. I felt we answered every one of his points cogently. Perhaps the most telling was when he claimed to be quoting me, but I pointed out that he was citing a block quotation. Those words were direct quotations from someone else—not my voice, but the material I was analyzing.

At one point, while I was articulating some argument, the beeper went off. For months I had awaited it, and now it went off. That meant my brother and I had a little over an hour to get my mother and ourselves to LDS Hospital. A liver was en route. Flustered, I had to explain the situation to the men and excuse myself to start making calls, while they continued their discussion.

It turned out that beepers sometimes beep in vain. It was a false alarm.

I made a second appeal, accusing the various committees of being blinded to my record because of the religious tensions surrounding the case. Rex Lee and BYU Provost Bruce Hafen took advantage of that appeal to bring allegations of academic citizenship violations against me, by which they meant that they felt I had not fulfilled my obligations as a member of the university community. They had already besmirched my scholarship, one of the three areas in which faculty are evaluated. Now they were challenging my citizenship and service to BYU and the larger community. Only the quality of my teaching was left untouched. The judges of last resort became, instead, prosecuting attorneys. This was the first time anyone had ever accused me of violating the moral standards of good citizenship because of the Mormon masculinity article or for any other reason. I felt we dealt well with the issues; but at the very end one of the vice presidents, Robert Webb, I believe, spoke for perhaps the first time to deliver the coup de grace. He said, “David, if it ever comes to a conflict between your discipline and the Church, with which will you side?” In honesty I answered, “I hope the Church.” But I knew it was not good enough.

***

I spent October of 1993 writing a paper to be presented as the Glen Vernon Memorial Lecture at the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion meetings in Chapel Hills, North Carolina. It was a great honor for a junior scholar to be asked to present a named lecture at a professional meeting, and I put into it all of the energy that did not go into the daily care of my mother and constant trips to doctors’ offices.

As I left to fly to the conference, I had a strong feeling of dread. When I arrived, I tried to call home. The phone rang busy for almost an hour. I stayed by the phone to keep trying. Finally I got through. My mother had collapsed with massive bleeding from her esophagus. The liver had caused the blood vessels there to expand and become ever thinner. Finally they broke. Before the beeper could legitimately sound, I was at an airport in North Carolina.

Fortunately the paramedics had arrived almost immediately. They rushed her to St. Mark’s Hospital where her surgeon happened to be at that precise moment. In the emergency room, I am told, he had an argument with the staff over protocol. They refused his instructions. So he had my brother forcefully push down on bags of blood to get it quickly in her system and make up for the lost blood. They life-flighted her to LDS Hospital while I was trying to catch the next flight back to Salt Lake. Nothing was flying out until the next morning. I left my paper for someone else to read and I returned to Salt Lake devastated, exhausted, and frightened.

***

After Christmas 1993, I dreaded returning to teach one final semester of classes at BYU where I had been so publicly shamed. I sat in my darkened room and sounded the wind chimes over and over. It seemed there was no one around. Almost no friends, no support. I had only the chimes sounding over and over in the dark.

I love teaching, but that semester I dreaded going to class. It seemed somehow indecent to have to remain at the university for another five months after they had fired me. When I would arrive on campus, I would walk toward my office or classroom, head up and eyes forward but focused on some invisible point, without seeing the people around me. I knew everyone had seen me in the press.

One day I was walking through the bookstore when I heard my name. Instead of continuing forward, eyes fixed ahead, I turned. It was a former student who had formed part of a group who wanted to study liberation theology. I taught an extra class so they could have the chance to read and discuss this important current of Latin American thought.

He said, “David, I have to ask you something. What is the real reason you were fired?”

I said I did not know; there seemed to be many shifting issues but it was hard to put my finger on precisely what the reasons were, particularly since the university would not tell me. When I had asked Alan Wilkins, he said I could sue and maybe then they would tell me.

The student, eyes on the ground, shifted and hesitated. “They’re saying the real reason is that you were sleeping with your male students. Look, a lot of us fought for you. We put our necks on the line, and I have to know if it is true.”

I felt as if someone had thrust a dagger repeatedly into my chest. I do not know how I managed to stay standing and continue talking with him. No, I told him. It was not true. I had heard a similar rumor that the “real” reason was a long-term affair with a female staff person. Now the rumor-mongering had dragged my students into the mud. For days I walked dazed, that accusation ringing in my head, before I realized that it was how those opposing me tried to explain to themselves my interest in the students and my dedication to teaching. Originally the administration attacked me for inadequate scholarship; then they besmirched my citizenship. Now through the rumor mill, someone was grinding my reputation as a teacher out of existence.

***

Toward the end of February 1994, I received a phone call from the American Association of University Professors. They said they could not intervene in my case, although it was filled with red flags. Had there been one more witness, they said, to a conversation between Rex Lee and me, they would have initiated an investigation.

At the first hearing, Rex Lee passed me a note in Spanish, asking if he could meet with me. Rex was courtly and solicitous. He always treated me with respect but for some reason I was also aware that under that surface of decorum was a wrestling match, although I was never quite sure exactly who was wrestling whom.

He asked me why I didn’t just get a job somewhere else and resign from the university. I said that academic hiring wasn’t that easy; it was a process requiring months, generally involving national searches. The next phase of academic hiring in my field would not start until the next fall. He said that, although I had presented a creditable appeal, there was no way that I would prevail and that I should save myself embarrassment by leaving.

I was stunned. Here was the judge of last resort in my case admitting his prejudice against my case before I had even finished presenting it. He added, very delicately, that the board of trustees would never allow the university to find in my favor, no matter what arguments I might raise. He then offered to speak with them and see if he could arrange some kind of payment to encourage me to resign.

I told him that I had worked hard on my appeal and that I believed in the process. I also said that I believed in the academic freedom issues and that they needed ventilation, but that I would listen. Later he called me with an insulting financial offer, which I rejected, and the appeal continued.

President Lee told me we were cousins. Evidently his family had been sealed in the temple into the Shumway family. My grandmother was a Shumway. In my mind I started seeing this struggle as filled with kin ties and histories that went far beyond the immediate event. It was a social drama with evidently clean lines in public, but behind the scenes were confusing and overlapping connections and histories.

A friend told me, on credible evidence, that, on a number of occasions, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve phoned President Lee and challenged his manhood because he “wasn’t doing anything” about Knowlton and Farr. Cecilia Konchar Farr, a professor of English, was eventually dismissed along with three others at the third-year review. I was told that President Lee was ordered to fire us but that he resisted, with considerable difficulty, arguing that the process needed to be allowed to play itself out. He held out for institutional order. I do not know the truthfulness of this report, but I would like to have known the pressures exerted on this man dying of cancer who had been known in the Reagan administration for his integrity. President Lee had told me he had been warned that academic freedom would be the hardest issue he would ever face as president of the university.

***

One day in Bolivia, starting at thirteen thousand feet, I climbed the steps leading up the hill Calvary. I carried stones with me, as if I were a pilgrim, to leave them like cares or sins at each station of the cross. I arrived at the halfway point, winded and tired from the altitude, my nails starting to turn a light shade of blue. I sat on a boulder and watched a rezador, a native offerer of prayers, do his preparations. For some reason I was drawn to him and asked if he would pray for me. He burned incense and gave it to the winds and mountains. He offered beer to the earth, the cross, and the saints. And he blessed me with it as I repeated after him a set of prayers to cleanse me of cares.

Another part of me could not believe I was undergoing this ritual, standing between the massive Cerro Juana, the highest peak nearby, and the rolling waters of the lake that splashed against the foot of the hill Cal vary more than a hundred feet below. This was not my religion. It was not my culture. It was not my way. Yet off and on over two decades I had seen the rezadores at work. They moved me.

***

After my mother came home from the hospital, my brothers, their families, and I nursed her with the help of various home care nurses. We would bathe her, change her dressings, administer her medication intravenously, check her temperature and her blood pressure, bathe her and prepare special meals. This was the rhythm of our days, as she gradually gained strength and began to care for herself. As spring came, then summer, she started going out to church and to visit friends. The promise of a new life stretched falsely before her.

During the spring semester of 1994, after I had been fired and was living in a new ward, a new bishop, who was a workmate of my former bishop, called me to be gospel doctrine teacher. It was a challenge to go before the class and teach the scriptures. Inside I ached. I did not know what I believed any more. I felt beaten and mauled. But I had to stand and teach the official view of the Old Testament. I put a lot of time into preparation. I went to the library and worked through the main biblical commentaries and other works. I thought through the structure of history and the nature of Old Testament society. And to the degree that this information would not contradict too overtly the manual, I presented it as explanatory background. Most people seemed to love it, and the class kept getting bigger.

After almost every class, however, someone would leave a note on the music stand that held my manual and scriptures accusing me of heresy. Obviously someone in the class did not like what I—and many of the people in the class—had to say. That person held a different view of Mor monism from mine. But instead of speaking to me, instead of arguing for his interpretation, he would leave a handwritten note on the stand calling me to ideological repentance.

Furthermore, the bishop told me that “spies from the Church Office Building were coming to listen closely” to what I might say. I doubt that these were the same persons. The tension of this surveillance and the discrepancy between my scarred but aching soul and the vigilance I had to exercise over what I said was wearying.

Later, when I had accepted a teaching position in Colorado, I tried to go to church, but I could not. Instead of worshipping, I would either get very angry or very depressed, so I stopped attending. Similarly I could no longer wear my garments. The fabric hurt, like so many fine needles poking me, every time I would put them on. So I learned to walk without the clothing and without the institution that had informed every waking moment of mine for a very long time—arguably for my whole life. Life felt very empty and lonely. I did not know how to live without those clothes and that identity.

***

One day during my stay in Bolivia, I walked to my room and tried writing, but my laptop looked back at me vaguely accusingly, a bright empty light in a cold, dark room. I roamed the town’s streets watching people, as if by seeing their ordinary joys, hungers, and pains I could somehow unfold myself from that dry, faintly green point into a broad, outreaching leaf, while under my feet each single cobble made its rounded finality known.

“Señor David, Señor David.” I turned and looked into the broad, open smile in the round face of my tocayo. He and I shared the same name. When I first came to Copacabana to do field work, he was the first person I met. He had been standing just past the bus door, a twelve-year-old boy, inviting us to come to one of the hotels he represented. I walked with him, and he became my friend, assistant, and guide during the year I kept coming back to stay sometimes for months at a time. But I had not seen him in more than a decade.

He came running forward, a man now, tall and angular. “Señor Da vid, it is you.” And he drew me into the abrazo, the hug of recognition and greeting.

***

Three months later, wishing for life, my mother died.

“Guai a chi con gioia vitale

Vuole servire una legge ch’è dolore!”

(Woe to him who filled with vital joy

desires to serve a law that’s only sorrow)

—Pier Paolo Pasolini

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue