Articles/Essays – Volume 28, No. 4

Male-Male Intimacy among Nineteenth-century Mormons: A Case Study

In recent decades a growing number of scholarly journals have given serious attention to the “same-sex dynamics” of nineteenth-century Americans.[1] Included are such conservative publications as the New England Quarterly, Massachusetts Review, Victorian Studies, American Literary Realism, Journal of Social History, Journal of American History, American Historical Review, and U.S. News and World Report.[2] Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought entered this field in 1983 when Lavina Fielding Anderson discussed the same-sex love poetry of Kate Thomas (b. 1871) who published primarily in the LDS periodical, Young Woman’s Journal.[3]

In fact, most of these first explorations of same-sex dynamics emphasized the intense emotional and social relationships between nineteenth-century women. In 1963 William R. Taylor and Christopher Lasch discussed the “sorority” of such relationships, which Carol Lasser later defined as the “Sororal Model of Nineteenth-Century Female Friendship.”[4] In 1975 Carroll Smith-Rosenberg introduced the term “homosociality” into the analysis of these relationships.[5] By the 1980s the academic community had added male-male relationships to the study of same-sex dynamics in nineteenth-century America. Just as men have been researching and writing about female-female relationships, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Karen V. Hansen have been among the principal contributors to the examination of male-male “intimacy” and “intimate friendship” in the nineteenth century.[6]

Of nineteenth-century society, noted historian Peter Gay writes: “Passionate [same-gender] friendships begun in adolescence often survived the passage of years, the strain of physical separation, even the trauma of the partners’ marriage. But these enduring attachments were generally discreet and, in any event, the nineteenth century mustered singular sympathy for warm language between friends.” He adds that “the cult of friendship . . . flourishing unabated through much of the nineteenth [century], permitted men to declare their love for other men—or women for other women—with impunity.”[7] Because nineteenth-century Americans rarely referred to the sexual side of their marital relationships, neither Mormons nor any one else of that era would likely acknowledge if there were an erotic side to their same-sex relationships.[8] It was thus possible for nineteenth-century Americans to speak in the vernacular of platonic love while announcing their romantic and erotic attachments with persons of the same sex. Literary historians have observed this in the work of such nineteenth-century writers as Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Bayard Taylor, Herman Melville, William Dean Howells, Amy Lowell, George Santayana, Willa Cather, Henry James, and Mark Twain.[9] As Lowell’s biographer commented, “[T]hose who had the eyes to see it or the antennae to sense it” would recognize the homoromantic and homoerotic sub-text. Those without such sensitivities would not have discerned this deeper declaration.[10]

Although homoerotic attraction has probably always existed, nineteenth-century Americans (like many other contemporary non-Western societies) did not regard men and women as divided into us-them camps according to opposite-sex versus same-sex desire. In fact, the term “homosexual” did not even appear in American writings until 1892, when “heterosexual” was also used for the first time.[11] As historian E. Anthony Rotundo has commented, this lack of cultural categories for sexual orientation directly affected same-sex friendships.

To the extent that they did have ideas—and a language—about homosexuality, they thought of particular sexual acts, not of a personal disposition or social identity that produced such acts. . . . In a society that had no clear concept of homosexuality, young men did not need to draw a line between right and wrong forms of [physical] contact, except perhaps at genital play. . . . Middle-class culture [in nineteenth-century America] drew no clear line of division between homosexual and heterosexual. As a result young men (and women, too) could express their affection for each other physically without risking social censure or feelings of guilt.[12]

Of women in that era who wrote passionate love letters to one another and lived together, a recent article in U.S. News and World Report reports: “But Ruth Cleveland [sister of the U.S. president] and Evangeline Whipple loved in the waning years of another time, when the lines were drawn differently, the urge to categorize and dissect not so overpowering. Belonging to the 19th century, they were not yet initiated into the idea of ‘sexual identity.’”[13] Evidently, when society, culture, and religion impose no stigma, individuals feel no guilt for activities that seem natural to them.

Like American culture of the time, nineteenth-century Mormonism encouraged various levels of same-gender intimacy which most Mormons experienced without erotic response. In the nineteenth century it was acceptable for Mormon girls, boys, women, and men to walk arm-inarm in public with those of the same gender. It was acceptable for samesex couples to dance together at LDS church socials. School yearbooks pictured Mormon boys on high school athletic teams holding hands or resting one’s hand on a teammate’s bare thigh. It was also acceptable for Mormons to publicly or privately kiss those of the same sex “full on the lips,” and it was okay to acknowledge that they dreamed of doing so.[14] And as taught by their martyred prophet himself, it was acceptable for LDS “friends to lie down together, locked in the arms of love, to sleep and wake in each other’s embrace.”[15] These various same-sex dynamics made life somewhat easier and more secure for nineteenth-century Mormons who also felt the romantic and erotic side of same-sex relations. There was much that did not have to be hidden by Mormons who felt sexual interest for those of their same gender.

While nineteenth-century Americans rarely recorded explicit references to their erotic desires and behaviors, they did write of intense same-sex friendships in diaries and letters. Mormonism’s own recordkeeping impulse offers supportive evidence of such same-sex dynamics. The life of Evan Stephens, director of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir at the turn of the twentieth century, provides a case study in the use of social history sources, as well as being a prime example of the early Mormon celebration of male-male intimacy. For example, First Presidency counselor George Q. Cannon praised male-male love during a sermon on Utah’s Pioneer Day in 1881: “Men may never have beheld each other’s faces and yet they will love one another, and it is a love that is greater than the love of woman.” Cannon, like other nineteenth-century Americans, then emphasized the platonic dimension of this male-male love: “It exceeds any sexual love that can be conceived of, and it is this love that has bound the [Mormon] people together.”[16]

Evan Stephens (b. 1854) directed the Tabernacle Choir from 1890 until he retired in 1916. The Contributor, the LDS periodical for young men, once praised Stephens as a man who in falsetto “could sing soprano like a lady, and baritone in his natural voice.”[17] A tireless composer, Stephens wrote the words and music for nineteen hymns that remain in the official LDS hymn book today, more than by any other composer.[18]

The small, tightly-knit Mormon community at church headquarters in Salt Lake City knew that Stephens never married. A family who had been acquainted with him for decades commented: “Concerning the reason he never married nothing could be drawn from him.”[19] His recent biographer also admitted: “Stephens’ relations with women were paradoxical” and “he avoided relationships with women.”[20] Imagine such a situation today when Mormons begin to whisper about a young man’s sexual orientation if he isn’t married by age twenty-six. Imagine the reaction of such whisperers to the following description of the Tabernacle Choir director’s same-sex relationships as published in the LDS church’s The Children’s Friend.

In January 1919 the Friend began monthly installments about the childhood of “Evan Bach,” a play on the name of German composer J. S. Bach. Sixty-five-year-old Evan Stephens himself authored these thirdperson biographical articles that lacked a by-line.[21] Starting with the October issue, the Friend devoted the three remaining issues of the year to Stephens’s own account of the same-sex dynamics of his teenage life. During the next year seven issues of this church magazine emphasized different aspects of Stephens’s adult life, including his same-sex relationships.

Of thirteen-year-old Evan’s arrival in Willard, Utah, the autobiography began: “The two great passions of his life seemed now to be growing very rapidly, love of friendship and music. His day dreams . . . were all centered around imaginary scenes he would conjure up of these things, now taking possession of his young heart.” The article continued: “The good [ward] choir leader was a lovable man who might have already been drawn to the blue-eyed, affectionate boy.”[22] It was this local choir leader “I most loved,” Evan had earlier written in the church’s Improvement Era, and the teenager “cr[ied] his heart out at the loss” when the twentythree-year-old chorister moved away. “’I wanted to go with him,” Evan confessed.[23]

Concerning the young male singers in the choir, the Children’s Friend continued: “Evan became the pet of the choir. The [young] men among whom he sat seemed to take a delight in loving him. Timidly and blushingly he would be squeezed in between them, and kindly arms generally enfolded him much as if he had been a fair sweetheart of the big brawny young men. Oh, how he loved these men, too . . .”[24] The “men” he referred to were in their teens and early twenties.

The Friend also acknowledged a physical dimension in Evan’s attraction to young men. Its author (Stephens) marveled at “the picturesque manliness with those coatless and braceless [suspender-less] costumes worn by the men. What freedom and grace they gave, what full manly outlines to the body and chest, what a form to admire they gave to the creature Man . . . Those who saw the young men in their coatless costumes of early day, with their fine, free careless airs to correspond, [now] think of them as a truly superior race of beings.”[25]

A continuation of this third-person autobiography in the Friend related that from ages fourteen to sixteen, Evan lived with a stonemason, Shadrach Jones, as his “loved young friend.” The article gave no other reason for the teenager’s decision to leave the home of his devoted parents in the same town. Evan’s employment as Shadrach’s helper did not require co-residence.[26] At the time Jones was in his late thirties and had never fathered a child by his wife.[27] After briefly returning to his family’s residence in 1870, Evan left them permanently. At age sixteen Stephens moved in with John Ward who was his same age and “Evan’s dearest friend.”[28]

Evan explained, “Without ‘John’ nothing was worthwhile. With him, everything; even the hardest toil was heaven.” He added, “What a treasure a chum is to an affectionate boy!”[29] The two friends were accustomed to sleeping in the same bed, since there were eight other children in the Ward family’s house at the time.[30]

After three years in the cramped family’s house, the two young men moved out together. “In my twentieth year [age nineteen],” Evan bought a two-room house (sitting room and a bedroom), and John moved in. The Children’s Friend said that while these nineteen-year-olds were “batching it … [this] was a happy time for Evan and John.” A photograph of Evan standing with his hand on John’s shoulder is captioned: “WITH HIS BOY CHUM, JOHN [J.] WARD, WHEN ABOUT 21 YEARS OLD.”[31]

After six years of living with Evan, John married in 1876, but Evan remained close. The census four years later showed him as a “boarder” just a few houses from John, his wife, and infant. After the June 1880 census, Stephens left their town of Willard to expand his music career. John fathered ten children before Evan’s biography appeared in The Children’s Friend. He named one of his sons Evan.[32]

That article did not mention several of Evan’s other significant “boy chums.” Shortly after twenty-six-year-old Stephens moved to Logan in 1880, he met seventeen-year-old Samuel B. Mitton, organist of the nearby Wellsville Ward. Mitton’s family later wrote: “From that occasion on[,] their friendship grew and blossomed into one of the sweetest relationships that could exist between two sensitive, poetic musicians.”[33] In 1882 Evan moved to Salt Lake City to study with the Tabernacle organist, but “their visits were frequent, and over the years their correspondence was regular and candid, each bringing pure delight to the other with these contacts.” Then in the spring of 1887 Samuel began seriously courting a young woman.[34]

According to Stephens, that same year “Horace S. Ensign became a regular companion [of mine] for many years.” Horace was not quite sixteen years old, and Evan was thirty-three.[35] Evan’s former teenage companion, Samuel Mitton, married the next year at age twenty-five and later fathered seven children.[36] Still, Evan and Samuel wrote letters to each other, signed “Love,” during the next decades.[37]

As for Evan and his new teenage companion, after a camping trip together at Yellowstone Park in 1889, Horace lived next door to Evan for several years. When Horace turned twenty in 1891, he began living with thirty-seven-year-old Evan.[38] In 1893 he accompanied the conductor alone for a two-week trip to Chicago. A few months later they traveled to Chicago again when the Tabernacle Choir performed its award-winning concert at the 1893 World’s Fair.[39] They were “regular companion[s]” until Horace married in 1894 at age twenty-three. The two men remained close, however. Evan gave Horace a house as a wedding present and appointed him assistant conductor of the Tabernacle Choir. Eventually, Horace Ensign fathered four children and became an LDS mission president.[40]

Whenever Stephens took a long trip, he traveled with a young male companion, usually unmarried. When the Tabernacle Choir made a tenday concert tour to San Francisco in April 1896, Stephens traveled in the same railway car with Willard A. Christopherson, his brother, and father. The Christophersons had lived next to Stephens since 1894, the year Horace Ensign married.[41] In August 1897 forty-three-year-old Stephens took nineteen-year-old “Willie” Christopherson on a two-week camping trip to Yellowstone Park, but Evan reassured the now-married Horace Ensign in a letter from there that “you are constantly in my mind. . .” Like Horace, Willard was a member of the Tabernacle Choir where he was a soloist.[42] During a visit to the east coast in 1898 Evan simply referred to “my accompanying friend,” probably Christopherson.[43]

Stephens’s primary residence in Salt Lake City had an address listed as “State Street 1 north of Twelfth South” until a revision of the streetnumbering system changed the address to 1996 South State Street. A large boating lake nearly surrounded this house which stood on four acres of land. In addition to his house, Evan also stayed in a downtown apartment.[44] Willard Christopherson had lived next to Evan’s State Street house from 1894 until mid-1899, when (at age twenty-two) he began sharing the same downtown apartment with forty-six-year-old Evan.[45]

In early February 1900 Evan left for Europe with “my partner, Mr. Willard Christopherson.”[46] After staying in Chicago and New York City for a month, Evan and “his companion” Willard boarded a ship and arrived in London on 22 March. They apparently shared a cabin-room. In April Evan wrote the Tabernacle Choir that he and “Willie” had “a nice room” in London.[47]

Evan left Willie in London while he visited relatives in Wales, and upon his return “we decided on a fourteen days’ visit to Paris.” Stephens concluded: “My friend Willard stayed with me for about two months after we landed in England, and he is now in the Norwegian mission field, laboring in Christiania.” Evan returned to Salt Lake City in September 1900, too late to be included in the federal census.[48] City directories indicate that Evan did not live with another male while Christopherson was on his full-time LDS mission.[49]

In March 1902 Evan returned to Europe to “spend a large portion of his time visiting, Norway, where his old friend and pupil, Willard Christopherson,” was on a mission.[50] During his ocean trip from Boston to Liverpool, Evan wrote that “I and Charlie Pike have a little room” aboard ship. Although he roomed with Stephens on the trip to Europe, twenty-yearold Charles R. Pike was on route to an LOS mission in Germany. Like Evan’s other traveling companions, Charles was a singer in the Tabernacle Choir—since the age of ten in Pike’s case.[51] While visiting Norway, Evan also “had the pleasure of reuniting for a little while with my old or young companion, Willard, sharing his labors, cares and pleasures while letting my own rest.”[52]

Willard remained on this mission until after Evan returned to the United States.[53] After Willard’s return, he rented an apartment seven blocks from Evan, where he remained until his 1904 marriage.[54]

That year seventeen-year-old Noel S. Pratt began living with fiftyyear-old Stephens at his State Street house. Uke Ensign and Christopherson before him, Pratt was a singer in Evan’s Tabernacle Choir. He was also an officer of his high school’s junior and senior class at the LDS University Salt Lake City, where Stephens was Professor of Vocal Music.[55] The LDS Juvenile Instructor remarked that Pratt was one of Evan’s “numerous boys,” and that the Stephens residence “was always the scene of youth and youthful activities.”[56]

In 1907 Evan traveled to Europe with his loyal niece-housekeeper and Pratt. Evan and the twenty-year-old apparently shared a cabin-room aboard ship during the two crossings of the Atlantic.[57] Before their trip together, Pratt lived several miles south of Evan’s house. After their return in 1907, he moved to an apartment a few blocks from Evan. When the choir went by train to the west coast for a several-week concert tour in 1909, Noel shared a Pullman stateroom with Evan. With them was Evan’s next companion, Tom S. Thomas. Pratt became Salt Lake City’s municipal judge, did not marry W1til age thirty-six, divorced shortly afterward, and died shortly after.[58]

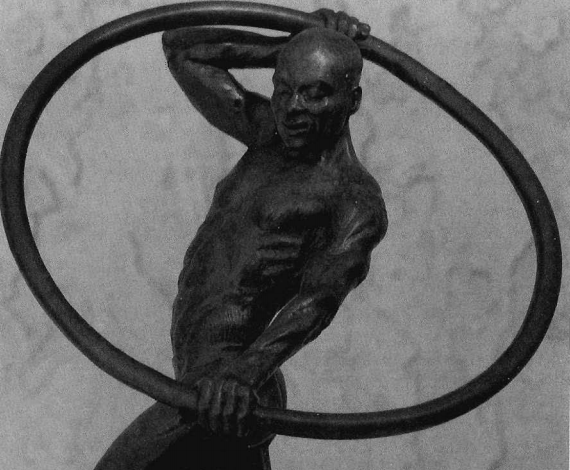

The intensity of Evan’s relationship with Thomas is suggested by a photograph accompanying the 1919 article of Children’s Friend. The caption read: “Tom S. Thomas, a grand-nephew and one of Professor Evan Stephens’ dear boy chums.” This 1919 photograph had skipped from Evan’s live-in companion of the 1870s to his most recent, or as The Friend put it, “the first and last of his several life companions, who have shared his home life.”[59]

Born in 1891, Tom S. Thomas, Jr., was an eighteen-year-old inactive Mormon when he began living with fifty-five-year-old Evan. Tom moved in with Stephens near the time he traveled to Seattle with the choir director in 1909.[60] They shared a house with the matronly housekeeper who was both Tom’s second cousin and Evan’s grand-niece. The housekeeper remained a non-Mormon as long as Evan lived.[61] Thomas had apparently stopped attending school while he lived in Maho with his parents and also during his first year living with Stephens. At age nineteen, with Evan’s encouragement, he began his freshman year of high school at the LOS University in Salt Lake City. Another of Evan’s boy-chums described Tom as “a blond Viking who captured the eye of everyone as a superb specimen of manhood.” The impressive and mature-looking Thomas be- came president of his sophomore class in 1911, and his final yearbook described him thus: “Aye, every inch a king,” then added: Also a ‘Queener.’”[62]

During the last years Evan and Thomas lived together in Utah, the city directory no longer listed an address for Tom but simply stated that he “r[oo]ms [with] Evan Stephens.”[63] He accompanied Evan on the choir’s month-long trip to the eastern states in 1911, the same year he was class president at the LDS high school. However, the choir’s business manager George D. Pyper deleted Tom’s name from the passenger list of the choir and “tourists” as published by the church’s official magazine, Improvement Era.[64] Pyper may have been uncomfortable about same-sex relationships since 1887, when he served as the judge in the first trial of a sensational sodomy case involving teenage boys.[65]

After they had lived together for seven years, twenty-five-year-old Tom prepared to move to New York City to begin medical school in 1916. Evan had put Tom through the LDS high school and the University of Utah’s pre-medical program and was going to pay for his medical training, as well, but Stephens wanted to continue living with the younger man. He consequently resigned as director of the Tabernacle Choir in July. He later explained that he did this so that he could “reside, if I wished, at New York City, where I was taking a nephew I was educating as a physician, to enter Columbia University.”[66] Stephens gave up his career for the “blond Viking” who had become the love of his life.[67]

In October 1916 the Deseret Evening News reported the two men’s living arrangements in New York City: “Prof. Evan Stephens and his nephew, Mr. Thomas, are living at ‘The Roland,’ east Fifty-ninth street.” Columbia University’s medical school was located on the same street. Then the newspaper referred to one of Evan’s former boy-chums: “the same hostelry he [Stephens] used to patronize years ago when he was here for a winter with Mr. Willard Christopherson.” The report added that Tom intended to move into an apartment with eight other students near the medical school.[68] Stephens later indicated that Tom’s intended student-living arrangement did not alter his “desire” to be near the young man. A few weeks after the Deseret News article, the police conducted a well-publicized raid on a homosexual bathhouse in New York City.[69]

In November Stephens wrote about his activities in “Gay New York.” He referred to Central Park and “its flotsam of lonely souls-like myself-who wander into its retreats for some sort of companionship . . .” For New Yorkers who defined themselves by the sexual slang of the time as “gay/’ Evan’s words described the common practice of seeking same- sex intimacy with strangers in Central Park.[70] Just days after the commemorative celebration in April 1917 which brought him back to Utah, Stephens said he had “a desire to return ere long to my nephew, Mr. Thomas, in New York . . .”[71]

Evan apparently returned to New York later that spring and took up residence in the East Village of lower Manhattan. At least that is where the census showed Tom living within two years.[72] By then there were so many open homosexuals and male couples living in Greenwich Village that a local song proclaimed: “Fairyland’s not far from Washington Square.”[73] Long before Evan and Tom arrived, New Yorkers used “fairy” and “fairies” as derogatory nouns for male homosexuals.[74] In fact, just before Stephens said he intended to return to Tom in New York in 1917, one of the East Village’s cross-dressing dances (“drag balls”) was attended by 2,000 people—”the usual crowd of homosexualists,” according to one hostile investigator.[75]

Tom apparently wanted to avoid the stigma of being called a New York “fairy,” which had none of the light-hearted ambiguity of the “Queener” nickname from his high school days in Utah.[76] Unlike the openness of his co-residence with Stephens in Utah, Tom never listed his Village address in New York City’s directories.[77] However, Evan’s and Tom’s May-December relationship did not last long in Manhattan. “After some months,” Evan returned to Utah permanently, while Tom remained in the Village. Thomas married within two years and fathered two children.[78]

Shortly after Evan’s final return to Salt Lake from New York in 1917, he befriended thirty-year-old Ortho Fairbanks. Like most of Evan’s other Salt Lake City boy-chums, Ortho had been a member of the Tabernacle Choir since his mid-teens. Stephens once told him: “I believe I love you, Ortho, as much as your father does.” In 1917 Evan set up the younger man in one of the houses Stephens owned in the Highland Park subdivision of Salt Lake City. Fairbanks remained there until he married at nearly thirty-five-years-of-age. He eventually fathered five children.[79]

However, during the five-year period after Evan returned from New York City, he did not live with Fairbanks or any other male.[80] No one had taken Tom’s place in Evan’s heart or home. Two years after Fairbanks began living in the Highland Park house, The Children’s Friend publicly identified Evan’s former boy-chum Tom S. Thomas as the “last of his several life companions, who have shared his home life.”[81] There is no record of the letters Stephens might have written during this period to his now-married “blond Viking” in the east.

However, Thomas was not Evan’s last boy-chum. Three months after Fairbanks married in August 1922, Stephens (now sixty-eight) took a trip to Los Angeles and San Francisco with seventeen-year-old John Wallace Packham as ‘1tls young companion.” Packham was a member of the “Male Glee Club” and in student government of the LDS University (high school).[82] The Salt Lake City directory showed him living a few houses from Evan as a student in 1924-25. At that time Stephens privately described Wallace as the “besht boy I ish gott.” It is unclear why Stephens imitated a drunkard’s speech. This was the only example in his available letters.[83]

After Wallace moved to California in 1926, Evan lived with no other male. From then until his death, he rented the front portion of his State Street house to a succession of married couples in their thirties, while he lived in the rear of the house.[84]

When Evan prepared his last will and testament in 1927, twenty-twoyear-old Wallace was still in California, where Evan was supporting his education. Evan’s will divided the bulk of his possessions among the LDS church; his brother, his housekeeper-niece, and “Wallace Packham, a friend.” Packham eventually married twice and fathered two children.[85]

When Stephens died in 1930, one of his former boy-chums confided to his diary: “No one will know what a loss his passing is to me. The world will never seem the same to me again.”[86] Although Wallace received more of the composer’s estate than Evan’s former (and now much older) boy-chums, Stephens also gave small bequests to John J. Ward, Horace S. Ensign, Willard A. Christopherson, to the wife of deceased Noel S. Pratt, to Thomas S. Thomas, and Ortho Fairbanks.[87]

As a teenager, Stephens had doubted the marriage prediction of his psychic aunt: “I see you married three times1 two of the ladies are blondes, and one a brunette.” She added, “I see no children; but you will be very happy.”[88] Stephens fulfilled his aunt’s predictions about having no children and being happy. However, beginning with sixteen-year-old

John Ward a year later, he inverted his aunt’s prophecy about the gender and hair color of those described by the LDS magazine as “his several life companions.” Instead of having more ”blondes” as wives, Stephens had more “brunettes” as boy-chums.[89]

The Children’s Friend even printed Evan’s 1920 poem titled “Friends” which showed that these young men had shared his bed:

We have lived and loved together,

Slept together, dined and supped,Felt the pain of little quarrels,

Then the joy of waking up;Held each other’s hands in sorrows,

Shook them hearty in delight,Held sweet converse through the day time,

Kept it up through half the night.[90]

Whether or not Stephens intended it, well-established word usage allowed a sexual meaning in that last line of his poem about male bedmates. Since the 1780s “keep it up” was slang for “to prolong a debauch.”[91]

Seventeen years before his poem “Friends” contained a possible reference to sexual intimacy, Stephens publicly indicated that there was a socially forbidden dimension in his same-sex friendships. In his introduction to an original composition he published in the high school student magazine of LDS University, Evan invoked the well-known examples of Ruth and Naomi, David and Jonathan, Damon and Pythias, and then referred to ”one whom we could love if we dared to do so.” Indicating that the problem involved society’s rules, Stephens explained that “we feel as if there is something radically wrong in the present make up and constitution of things and we are almost ready to rebel at the established order.” Then the LDS high school’s student magazine printed the following lines from Evan’s same-sex love song: “Ah, friend, could you and I conspire/ To wreck this sorry scheme of things entire,/ We’d break it into bits, and then-/ Remold it nearer to the heart’s desire.”[92] The object of this “desire” may have been eighteen-year-old Louis Shaw, a member of the Male Glee Club at the LDS high school where Stephens was the music teacher. Shaw later became president of the Bohemian Club, identified as a social haven for Salt Lake City’s homosexuals.[93]

The words of this 1903 song suggest that Stephens wanted to live in a culture where he could freely share erotic experience with the young men he openly loved in every other way. Historical evidence cannot demonstrate whether he actually created a private world of sexual intimacy with his beloved boy-chums who “shared his home life.” It can only be a matter of speculation whether Evan had sexual relations with any of the young men he loved, lived with, and slept with throughout most of his life. Of his personal experiences, he confessed: “some of it [is] even too sacred to be told freely[,] only to myself.”[94]

If there was unexpressed erotic desire in the life of Evan Stephens, it is possible that only Stephens felt it, since all his boy-chums eventually married. Homoerotic desire could have been absent altogether, unconsciously sublimated, or consciously suppressed. However, historian John D. Wrathall cautions:

Marriage, even “happy” marriage (however we choose to define “happy”), is not proof that homoeroticism did not play an important and dynamic role in a person’s relationships with members of the same sex. Nor is evidence of strong homoerotic attachments proof that a man’s marriage was a sham or that a man was incapable of marriage. It is clear, however, that while strong feelings toward members of both sexes can co-exist, the way in which such feelings are embodied and acted out is strongly determined by culture.

Wrathall adds that lifelong bachelorhood also “should not be interpreted as a suggestion that these men were ‘gay,’ any more than marriage allows us to assume that they were ‘heterosexual.'”[95] By necessity this applies to the lifelong bachelorhood of Evan Stephens as well as to the marriages of his former boy-churns and their fathering of numerous children.

Whether or not Evan’s male friendships were explicitly homoerotic, both published and private accounts showed that the love of the Tabernacle Choir director for young men was powerful charismatic, reciprocal, and enduring. For example, as a member of the Tabernacle Choir from age ten until Stephens’ s retirement, Charles R. Pike traveled with Evan (but never resided with him) and / was a close friend of Elder Stephens until his death.”[96] Evan’s own biographer concluded that Stephens “attached himself passionately to the male friends of his youth, and brought many young men, some distantly related, into his home for companionship…”[97]

Probably few, if any, other prominent Mormon bachelors shared the same bed with a succession of beloved teenage boys and young men for years at a time as did Stephens. The Children’s Friend articles invite the conclusion that sexual intimacy was part of the personal relationship which Stephens shared only with young males.

For Mormons who regarded themselves as homosexual, lesbian, or bisexual, and had “the eyes to see it or the antennae to sense it,” The Children’s Friend of 1919 endorsed their own romantic and erotic same-sex relationships. (About this time Mildred J. Berryman began a study of homosexually-identified men and women in Salt Lake City.[98]) However, for the majority of Mormon readers whose same-sex dynamics had no romantic or erotic dimensions, this publication passed without special notice. The nineteenth-century’s “warm language between friends” covered a multitude of relationships. Evan Stephens and his “boy chums” were only one example.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] For more extensive discussion and bibliography from a national and cross-cultural perspective, see D. Michael Quinn, Same-sex Dynamics among Nineteenth-century Americans: A Mormon Example (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996).

[2] William R. Taylor and Christopher Lasch, “Two ‘Kindred Spirits’: Sorority and Family in New England, 1839–1846,” New England Quarterly 36 (Mar. 1963): 23–41; Lillian Faderman, “Emily Dickinson’s Letters to Sue Gilbert,” Massachusetts Review 18 (Summer 1977): 197–225; Robert K. Martin, “The ‘High Felicity’ of Comradeship: A New Reading of Roderick Hudson,” American Literary Realism 11 (Spring 1978): 100–108; Michael Lynch, “‘Here Is Adhesiveness’: From Friendship To Homosexuality,” Victorian Studies 29 (Autumn 1985): 67–96; E. Anthony Rotundo, “Romantic Friendship: Male Intimacy and Middle-Class Youth in the Northern United States, 1800–1900,” Journal of Social History 23 (Fall 1989): 1–25; John D. Wrathall, “Provenance as Text: Reading the Silences around Sexuality in Manuscript Collections,” Journal of American History 79 (June 1992): 165–78; “Intimate Friendships: History Shows that the Lines between ‘Straight’ and ‘Gay’ Sexuality Are Much More Fluid than Today’s Debate Suggests,” U.S. News and World Report 115 (5 July 1993): 49–52; Mary W. Blanchard, “Boundaries and the Victorian Body: Aesthetic Fashion in Gilded Age America,” American Historical Review 100 (Feb. 1995): 40.

[3] Lavina Fielding Anderson, “Ministering Angels: Single Women in Mormon Society,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 16 (Autumn 1983): 68-69; also discussions of Kate Thomas in Rocky O’Donovan, “‘The Abominable and Detestable Crime Against Nature’: A Brief History of Homosexuality and Mormonism, 1840–1980,” in Brent Corcoran, ed., Multiply and Replenish: Mormon Essays on Sex and Family (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1994), 128, 129–31; Quinn, Same-sex Dynamics among Nineteenth-century Americans.

[4] Taylor and Lasch, “Two ‘Kindred Spirits,’” also Judith Becker Ranlett, “Sorority and Community: Women’s Answer To a Changing Massachusetts, 1865–1895,” Ph.D. diss., Brandeis University, 1974; Carol Lasser, “‘Let Us Be Sisters Forever’: The Sororal Model of Nineteenth-Century Female Friendship,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 14 (Autumn 1988): 158–81.

[5] Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, “The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations Between Women in Nineteenth-Century America,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1 (Autumn. 1975): 1-29, reprinted in Nancy F. Cott and Elizabeth H. Pleck, eds., A Heritage of Her Own: Toward a New Social History of American Women (New York: Touchstone/Simon and Schuster, 1979), in Michael Gordon, ed., The American Family in Social-Historical Perspective, 3rd ed. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), and in Caroll Smith-Rosenberg, Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987).

[6] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985); Karen V. Hansen, “‘Helped Put in a Quilt’: Men’s Work and Male Intimacy in Nineteenth-Century New England,” Gender and Society 3 (Sept. 1989): 334–54; Karen V. Hansen, “‘Our Eyes Behold Each Other’: Masculinity and Intimate Friendship in Antebellum New England,” in Peter M. Nardi, ed., Men’s Friendship: Research on Men and Masculinities (Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1992), 35–58; also Leonard Harry Ellis, “Men Among Men: An Exploration of All-Male Relationships in Victorian America,” Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 1982; John W. Crowley, “Howells, Stoddard, and Male Homosocial Attachment in Victorian America,” in Henry Brod, ed., The Making of Masculinities: The New Men’s Studies (Boston: Allen and Unwin, 1987); Jeffrey Richards, “‘Passing the Love of Women’: Manly Love and Victorian Society,” in J.A. Mangan and James Walvin, eds., Manliness and Morality: Middle-Class Masculinity in Britain and America, 1800–1940 (Manchester, Eng.: Manchester University Press, 1987), 92–122; Donald Yacovone, “Abolitionists and the ‘Language of Fraternal Love,’” in Mark C. Carnes and Clyde Griffen, eds., Meanings for Manhood: Constructions of Masculinity in Victorian America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).

[7] Peter Gay, The Bourgeois Experience: Victoria to Freud, vol. 2, The Tender Passion (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 217.

[8] Still some contemporary readers require that kind of explicit acknowledgement of sex acts on the part of people involved in demonstrably romantic, long-term relationships during which they shared a bed with a loved one of the same gender. See Blanche Wiesen Cook, “The Historical Denial of Lesbianism,” Radical History Review 20 (Spring/Summer 1979): 60–65; Leila J. Rupp, “‘Imagine My Surprise’: Women’s Relationships in Historical Perspective,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies 5 (Fall 1980): 61–62, 67; Walter L. Williams, The Spirit and the Flesh: Sexual Diversity in American Indian Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1986), 162; Sheila Jeffreys, “Does It Matter if They Did It?” in Lesbian History Group, Not a Passing Phase: Reclaiming Lesbians in History, 1840–1985 (London: The Woman’s Press, Ltd., 1993), 23.

[9] By nineteenth-century authors, I mean those who reached adulthood in the nineteenth century, even if they published in the twentieth century. Among other works, see Newton Arvin, Herman Melville (New York: William Sloan Associates, 1950), 128–30; Leslie A. Fiedler, Love and Death in the American Novel (New York: Criterion Books, 1960), 522–38; Gustav Bychowski, “Walt Whitman: A Study in Sublimination,” in Henry Ruitenbeck, ed., Homosexuality and Creative Genius (New York: Astor-Honor, 1967), 140–81; John Cody, After Great Pain: The Inner Life of Emily Dickinson (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press /Harvard University Press, 1971), 135–52, 176–84; Walter Loewenfels, ed., The Tenderest Lover: The Erotic Poetry of Walt Whitman (New York: Dell, 1972); Robert K Martin, “Whitman’s Song of Myself: Homosexual Dream and Vision,” Partisan Review 42 (1975), 1:80–96; Edwin Haviland Miller, Melville (New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1975), 234–30; John Snyder, The Dear Love of Man: Tragic and Lyric Communion in Walt Whitman (The Hague: Mouton, 1975); Jeffrey Meyers, Homosexuality and Literature, 1890–1930 (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1977), 20–31; Robert K Martin, “The ‘High Felicity’ of Comradeship: A New Reading of Roderick Hudson,” American Literary Realism 11 (Spring 1978): 100–108; Georges-Michel Sarette, Like a Brother, Like a Lover: Male Homosexuality in the American Novel and Theater from Herman Melville to James Baldwin, trans. Richard Miller (Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1978), 12–13, 73, 78–83, 197–211; Robert K. Martin, “Bayard Taylor’s Valley of Bliss: The Pastoral and the Search for Form,” Markham Review 9 (Fall 1979): 13–17; Robert K. Martin, The Homosexual Tradition in American Poetry (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979), 3–89, 97–114, 676–90; Deborah Lambert, “The Defeat of a Hero: Autonomy and Sexuality in My Antonia,” American Literature 53 (Jan. 1982): 676–90; Calvin Bedient, “Walt Whitman: Overruled,” Salmagundi: A Quarterly of the Humanities and the Social Sciences, 58–59 (Fall 1982–Winter 1983): 326–46; Richard Hall, “Henry James: Interpreting an Obsessive Memory,” Journal of Homosexuality 8 (Spring–Summer 1983), 83–97; Elizabeth Stevens Prioleau, The Circle of Eros: Sexuality In the Work of William Dean Howells (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1983), 110; Stephen Coote, ed., The Penguin Book of Homosexual Verse (London: Penguin Books, 1983), 203–205, 207–11; Sharon O’Brien, “‘The Thing Not Named,’: Willa Cather as a Lesbian Writer,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 9 (Summer 1984): 576–99; Vivian R, Pollack, Dickinson: The Anxiety of Gender (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984), 134–56; Joseph Cady, “DrumTaps and Nineteenth-Century Male Homosexual Literature,” in Joann P. Krieg, ed., Walt Whitman Here and Now (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985), 49–59; Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life (New York: Harper & Row, 1985), 83, 245–46, 497; John W. Crowley, The Black Heart’s Truth: The Early Career of W. D. Howells (Chapel Hill University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 89, 91, 97–99; Joanna Russ, “To Write ‘Like a Woman’: Transformation of Identity in the Work of Willa Cather,” and Timothy Dow Adams, “My Gay Antonia: The Politics of Willa Cather’s Lesbianism,” Journal of Homosexuality 12 (May 1986): 77–87, 89–98; Robert K. Martin, Hero, Captain, and Stranger: Male Friendship, Social Critique, and Literary Form in the Sea Novels of Herman Melville (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 6–7, 14–16, 26, 51–58, 63–64, 73–74, 105; Sandra Gilbert, “The American Sexual Poetics of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson,” in Sacvan Bercovitch, ed., Reconstructing American Literary History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986), 123–54; Eve Kosofosky Sedgwick, “The Beast in the Closet: James and the Writing of Homosexual Panic,” in Ruth Bernard Yeazell, ed., Sex, Politics, and Science in the Nineteenth Century Novel (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 148–86; Sharon O’Brien, Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 127–46, 205–22, 357–69; John McCormick, George Santayana: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), 49–52, 334; M. Jimmie Killingsworth, Whitman’s Poetry of the Body: Sexuality, Politics, and the Text (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 98–111; John W. Crowley, The Mask of Fiction: Essays on W D. Howells (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1989), 56–82; Susan Gillman, Dark Twins: Imposture and Identity in Mark Twain’s America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 34, 99, 119–22, 124; Robert K. Martin, “Knights-Errant and Gothic Seducers: The Representation of Male Friendship in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America,” in Martin Bauml Duberman, Martha Vicinus, and George Chauncey, Jr., eds., Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past (New York: New American Library, 1989), 169–82; Paula Bennett, “The Pea That Duty Locks: Lesbian and Feminist-Heterosexual Readings of Emily Dickinson’s Poetry,” in Karla Jay and Joanne Glasgow, eds., Lesbian Texts and Contexts: Radical Revisions (New York: New York University Press, 1990), 104–25; Zan Dale Robinson, Semiotic and Psychoanalytical Interpretation of Herman Melville’s Fiction (San Francisco: Mellon Research University Press, 1991), 53, 100; Byrne R. S. Fone, Masculine Landscapes: Walt Whitman and the Homoerotic Text (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1992); Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Tendencies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), 73–103, 167–76; John Bryant, Melville and Repose: The Rhetoric of Humor in The American Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 189–91, 217; David S. Reynolds, Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), 323–24, 391–402, 575–76; Byrne R. S. Fone, A Road to Stonewall, 1750–1969: Male Homosexuality and Homophobia in English and American Literature (New York: Twayne, 1995), 57–83.

[10] Jean Gould, Amy: The World of Amy Lowell and the Imagist Movement (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1975), 259. Gould also discusses the intimate relationship this lesbian poet shared with Mormon actress Ada Dwyer Russell, which likewise appears in Quinn, Same-sex Dynamics among Nineteenth-century Americans.

[11] James G. Kiernan, “Responsibility In Sexual Perversion,” Chicago Medical Reporter 3 (May 1892): 185–210, quoted in Jonathan Katz, Gay/Lesbian Almanac: A New Documentary (New York: Harper & Row, 1983), 232 and note; also George H. Wiedeman, “Survey of Psychoanalytic Literature on Overt Male Homosexuality,” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 10 (Apr. 1962): 386n, and Jonathan Ned Katz, The Invention of Heterosexuality (New York: Dutton, 1995), for Dr. Karl Maria Benkert’s introduction of the term “homosexual” and concept of “homosexuality” in Europe in 1869.

[12] Rotundo, “Romantic Friendship: Male Intimacy and Middle-Class Youth in the Northern United States, 1800–1900,” 10, 12; also Rotundo’s other statement of this view in his American Manhood: Transformations in Masculinity From the Revolution To the Modern Era (New York: Basic Books, 1993), 83–84, and Hansen, “‘Our Eyes Behold Each Other’: Masculinity and Intimate Friendship in Antebellum New England,” in Nardi, Men’s Friendship, 45.

[13] “Intimate Friendships,” U.S. News and World Report, 49.

[14] Quinn, Same-sex Dynamics among Nineteenth-century Americans.

[15] Joseph Smith sermon, 16 Apr. 1843, in Joseph Smith et al., History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Period I: History of Joseph Smith the Prophet, and . . . Period II: From the Manuscript History of Brigham Young and Other Original Documents, ed. B.H. Roberts, 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1902–32; 2d ed. rev [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1978]), 5:361. This is a slight variation on the original minutes of apostle and historian Willard Richards as reproduced in Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980), 195, and in Scott H. Faulring, ed., An American Prophet’s Record: The Diaries and Journals of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books/Smith Research Associates, 1987), 366, both of which show that History of Church failed to print a repetition of the word “locked” before “in each others embrace.” However, in his review of the book by Bhat and Cook, Dean C. Jessee claimed that the omitted word in the original manuscript was actually “rocked,” which intensifies the tenderness involved in same-sex bedmates as advocated by the Mormon prophet. See Jessee’s review in Brigham Young University Studies 21 (Fall 1981): 531.

[16] Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool, Eng.: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 22:365 (Cannon/1881); also Richards, “‘Passing the Love of Women’: Manly Love and Victorian Society,” in Mangan and Walvin, Manliness and Morality: Middle-Class Masculinity in Britain and America, 1800–1940, 92–122.

[17] Evan Stephens (b. 28 June 1854; d. 27 Oct. 1930); Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press and Andrew Jenson History Co., 1901–36), 1:740, 4:247; B. F. Cummings, Jr., “Shining Lights: Professor Evan Stephens,” The Contributor, Representing the Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Associations of the Latter-day Saints 16 (Sept. 1895): 655.

[18] Hymns of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), 11, 17, 18, 23, 33, 35, 55, 61, 74, 91, 118, 120, 183, 229, 243, 254,312,330,337, compared with index of authors and composers.

[19] Richard Bolton Kennedy, “Precious Moments With Evan Stephens, By Samuel Bailey Mitton And Others,” Salt Lake City, 25 May 1983, 8, Family History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah, hereafter LDS Family History Library.

[20] Ray L. Bergman, The Children Sang: The Life and Music of Evan Stephens With the Mormon Tabernacle Choir (Salt Lake City: Northwest Publishing, Inc., 1992), 182; also Dale A. Johnson, “The Life and Contributions of Evan Stephens,” M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1951, 73.

[21] Bergman, The Children Sang, 219, 279.

[22] “Evan Bach [Evan Stephens]: A True Story for Little Folk, by a Pioneer [Stephens himself],” The Children’s Friend 18 (Oct. 1919): 386, 387; for the acknowledgement of Stephens as the subject, see photograph: “PROFESSOR EVAN STEPHENS, ‘OUR EVAN BACH,’” Children’s Friend 18 (Dec. 1919): [468]; Evan Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 65 (Dec. 1930): 720.

[23] Evan Stephens, “Going Home To Willard,” Improvement Era 19 (Oct. 1916): 1090; “A Talk Given By Prof. Evan Stephens Before the Daughters of the Pioneers, Hawthorne Camp, Feb. 5, 1930,” typescript, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City, published as “The Great Musician,” in Kate B. Carter, ed., Our Pioneer Heritage, 20 vols. (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1958–77), 10:86; also Cummings, “Shining Lights,” 654; Bergman, The Children Sang, 49, 54.

[24] “Evan Bach [Evan Stephens]: A True-Story for Little Folk, by a Pioneer,” Children’s Friend 18 (Oct. 1919): 387. Although the phrasing of the sentence would lead the reader to expect the words “gently enfolded,” the published article used “generally enfolded.”

[25] “Evan Bach [Evan Stephens]: A True Story for Little Folk, by a Pioneer,” Children’s Friend 18 (Nov. 1919): 432. The pre-October installments of “Evan Bach [Evan Stephens]: A True Story for Little Folk, by a Pioneer,” contained two references which appear significant only by comparison with the emphasis on male-male love in the October–December 1919 installments. Children’s Friend 18 (Feb. 1919): 47 referred to “an old schoolboy [in Wales] for whom he secretly cherished intense admiration and childish affection.” Also Children’s Friend 18 (July 1919): 254 stated: “Most attractive of all to Evan Bach, were the merry smiling teamsters from the ‘Valley.’”

[26] “Evan Bach [Evan Stephens): A True Story for Little Folk, by a Pioneer,” Children’s Friend 18 (Nov. 1919): 430; Cummings, “Shining Lights: Professor Evan Stephens,” 655, noted that “Evan was employed by a stone mason, whose name was Shadrach Jones . . .”; also Bergman, The Children Sang, 57. Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 65 (Dec. 1930): 720, observed that from 1868 to 1870 he “helped to build stone walls and houses in Willard.”

[27] Shadrach Jones (b. 17 Nov. 1832 in Wales; md. 9 July 1853, no children; d. 1883) in Ancestral File, LDS Family History Library, hereafter LDS Ancestral File; Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:660–61; “[The Welch] In Box Elder County,” in Kate B. Carter, ed., Heart Throbs of the West, 12 vols. (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1939–51), 11:22; Teddy Griffith, “A Heritage of Stone in Willard,” Utah Historical Quarterly 43 (Summer 1975): 290–98. The U.S. 1870 Census for Box Elder County, Utah, sheet 78, mistakenly listed Jones by the first name “Frederick,” as a stone mason, with wife Mary who “cannot write.” The U.S. 1880 Census for Box Elder County, Utah, sheet 72, listed him as Shadrach, with consistent ages for him and wife Mary who “cannot write.”

[28] “Evan Bach [Evan Stephens]: A True Story for Little Folk, by a Pioneer,” Children’s Friend 18 (Oct. 1919): 389, (Dec. 1919): 470; also Evan Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 65 (Dec. 1930): 720; Bergman, The Children Sang, 56; also discussion of the Stephens-Ward relationship in O’Donovan, “‘The Abominable and Detestable Crone Against Nature,’” 142–43.

[29] Evan Stephens, “Going Home To Willard,” Improvement Era 19 (Oct. 1916): 1090; Bergman, The Children Sang, 56.

[30] U.S. 1870 Census of Willard, Box Elder County, Utah, sheet 78. For discussion of the same-sex sleeping arrangements of children in early Mormon families, see Quinn, Same-sex Dynamics among Nineteenth-century Americans.

[31] Evan Stephens, “Going Home to Willard,” Improvement Era 19 (Oct. 1916): 1092; “Evan Bach [Evan Stephens]: A True Story for Little Folk, by a Pioneer,” Children’s Friend 18 (Oct. 1919): 389, (Dec.1919): 471, (Oct.1919): 388; (Mar.1920): 97; Bergman, The Children Sang, 64–65. The Children’s Friend mistakenly gave John Ward’s middle initial as “Y.”

[32] U.S. 1880 Census of Box Elder County, Utah, sheet 73; John J. Ward (b. 23 Jan. 1854 at Willard, Utah; md. in 1876, ten children) in LDS Ancestral File. Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 65 (Dec. 1930): 720, said that in “1879—Accepted a position in Logan as organist of the Logan Tabernacle.” However, he accepted the position in 1880, remained a resident of Willard, and commuted to Logan as necessary (Bergman, The Children Sang, 69). The federal census of June 1880 showed him as a resident of Willard, not Logan. Some of the other dates in Evan’s autobiography are demonstrably in error.

[33] Samuel Bailey Mitton (b. 21 Mar. 1863; md. 1888, seven children; d. 1954); Victor L. Lindblad, Biography of Samuel Bailey Mitton (Salt Lake City: the Author, 1965), 69, 293, copy in Utah State Historical Society; Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:167–68.

[34] Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 65 (Dec. 1930): 721; Bergman, The Children Sang, 75–76; Lindblad, Biography of Samuel Bailey Mitton, 7, 293.

[35] Evan Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 66 (Jan. 1931): 10; Horace S. Ensign, Jr., was born 10 November 1871 and was probably still fifteen years old when Stephens met him in 1887. See Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:236.

[36] Windows of Wellsville, 1856–1984 (Providence, UT: Keith W. Watkins and Sons, 1985), 619; Lindblad, Biography of Samuel Bailey Mitton, 322–60.

[37] “From One Musician to Another: Extract from a letter written by Samuel B. Mitton, of Logan, to Evan Stephens of Salt Lake City,” updated, but signed “Love to you,” in Juvenile Instructor 65 (Oct. 1930): 599; Evan Stephens to Samuel B. Mitton, 7 Dec. 1924, in Kennedy, “Precious Moments With Evan Stephens,” 26–27; Stephens to Mitton, 14 Mar., 19 June 1921, in Bergman, The Children Sang, 236, 238.

[38] Salt Lake City Directory For 1890 (Salt Lake City: RL. Polk & Co., 1890), 274, 580, showed that Horace had a room in a house next to Evan’s house. Utah Gazetteer . . . 1892–93 (Salt Lake City: Stenhouse & Co., 1892), 284, 676, and Salt Lake City Directory, 1896 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1896), 282, 654, showed them living together. Evan referred to their trip “through the Park with me seven or eight years ago,” in his letter to Horace S. Ensign, 18 Aug. 1897, in Deseret Evening News, 26 Aug. 1897, 5.

[39] Evan Stephens, “The World’s Fair Gold Medal, Continued from the September number of ‘The Children’s Friend,’” Children’s Friend 19 (Oct. 1920): 420; “Making Ready To Go: Names of the Fortunate 400 Who Will Leave for Chicago Tomorrow,” Deseret Evening News, 28 Aug. 1893, 1; “The Choir Returns: Our Famous Singers Complete Their Tour,” Deseret Evening News, 13 Sept. 1893, 1.

[40] Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 66 (Mar. 1931): 133; and Salt Lake City Directory, 1898 (Salt Lake City: R. L. Polk & Co., 1898), 272, 712; “Horace Ensign Is Appointed: New Leader for the Tabernacle Choir Chosen Last Night,” Deseret Evening News, 19 Jan. 1900, 8; “Tabernacle Choir In Readiness for Tour of Eastern States,” Deseret Evening News, 21 Oct. 1911, ID, 1; Bergman, The Children Sang, 119, 214; Andrew Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Publishing Co., 1941), 374; Horace S. Ensign and Mary L. Whitney in LDS Ancestral File; “H. S. Ensign Dies At Home,” Deseret Evening News, 29 Aug. 1944, 9.

[41] List of occupants of “Car No. 6” in “The Choir’s Tour: Will Begin Monday Morning and Cover a Period of Ten Days,” Deseret Evening News, 11 Apr. 1896, 8; Salt Lake City Directory, 1894–5 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1894), 219.

[42] Stephens to Horace S. Ensign, 18 Aug. 1897, from Yellowstone Park, printed in full in “Evan Stephens’ Bear Stories,” Deseret Evening News, 26 Aug. 1897, 5; Bergman, The Children Sang, 203. Also, Mary Musser Barnes, “An Historical Survey of the Salt Lake Tabernacle Choir of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” M.A. thesis, University of Iowa, 1936, 93, 136. For the biography of Christopherson (b. 15 Oct. 1877), see Noble Warrum, Utah Since Statehood, 4 vols. (Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1920), 4:736; and J. Cecil Alter, Utah: The Storied Domain, 3 vols. (Chicago: American Historical Society, 1932), 2:484.

[43] “Stephens in Gotham,” Deseret Evening News, 23 Dec. 1898, 4; Bergman, The Children Sang, 205.

[44] Bergman, The Children Sang, 181, 215; “Famed Composer’s Home Gone,” Deseret News “Church News,” 28 May 1966, 6, noted that Stephens lived in this house when he wrote the song. for Utah’s statehood in 1896; also Brigham H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church . . . , 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1930), 6:338.

[45] Salt Lake City Directory, 1894–5, 219; Salt Lake City Directory, 1896 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1896), 214 (Willard Christopherson “bds e s State 2 s of Pearl av.”), and 74 (“Pearl av, from State e to Second East, bet Eleventh and Twelfth South”); Salt Lake City Directory, 1900 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1900), 190, 678. Willard is listed erroneously as “Christensen” in the middle of the “Christophersen” entries on 189–90. His father and brother were also erroneously listed as “Christensen” with Willard, but were listed as “Christophersen” before and after the 1900 directory. See Salt Lake City Directory, 1899 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1899), 203; entry about Willard “Christophersen” in Salt Lake City Directory, 1901 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk, 1901), 198. The 1899 directory was dated 1 May; the 1900 directory gave no specific month for its completion but was based on Willard Christopherson’s co-residence with Stephens prior to February 1900, when Willard moved to Europe. Therefore, Willard moved in with Evan sometime between May 1899 and January 1900.

[46] “Prof. Stephens’ European Trip: Will Begin Next Month and Last for About One Year,” Deseret Evening News, 2 Jan. 1900, 1.

[47] “Evans Stephens Is Home Again,” Deseret Evening News, 21 Sept. 1900, 8; Evan Stephens to Tabernacle Choir, 5 Apr. 1900, in “Evan Stephens On London,” Deseret Evening News, 5 May 1900, 11; Bergman, The Children Sang, 206.

[48] Evan Stephens to Tabernacle Choir, 24 Apr. 1900, from Paris, France, in “Evan Stephens In Wales,” Deseret Evening News, 12 May 1900, 11; also “Evan Stephens Is Home Again,” Deseret Evening News, 21 Sept. 1900, 8; Bergman, The Children Sang, 209; U.S, 1900 Census soundex has no entry for Evan Stephens (S-315).

[49] My method for ascertaining this was to check the Salt Lake City directories for the residence addresses of every male named in the last will and testament of Evan Stephens, also of the members of the Male Glee Club at the LDS high school where Stephens was Professor of Vocal Music at the time, and also the residence addresses of the male members of his music conductor’s training class at the LOS high school during these years.

[50] “Evan Stephens Off to Europe,” Deseret Evening News, 28 Mar. 1902, 2. Stephens claimed that Christopherson “is presiding over the mission,” but he was only presiding over the Christiania Conference of the mission. See Alter, Utah: The Storied Domain, 2:485; Andrew Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1927), 507.

[51] “Evan Stephens to His Juvenile Singers,” Deseret Evening News, 21 June 1902, II, 11. Although not published until June, this undated letter was written aboard ship in April after “we left Boston harbor . . . ” For Pike, see Frank Esshom, Pioneers and Prominent Men of Utah, Comprising Photographs-Genealogies-Biographies (Salt Lake City: Utah Pioneers Book Publishing Co., 1913), 1106; “Evan Stephens Music On Choir Program,” Deseret News “Church News,” 16 Mar. 1957, 15. The city directories show that Pike lived with his parents during the years before his trip to Europe with Stephens.

[52] “Prof. Stephens Home Again,” Deseret Evening News, 29 July 1902, 2.

[53] Ibid.: “No, I don’t bring with me friend Willard . . . . And it is possible it may be another summer before he is released [from his full-time mission].”

[54] Salt Lake City Directory, 1903 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1903), 234, 870; Willard Christopherson (b. 15 Oct. 1877) in LOS Ancestral File.

[55] LDS Ancestral File for Noel Sheets Pratt (b. 25 Dec. 1886; md. 1923; d. 1927); Salt Lake City Directory, 1904 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1904), 679, 801; Barnes, “An Historical Survey of the Salt Lake Tabernacle Choir,” 103; Gold and Blue 4 (July 1904): unnumbered page of third-year class officers; Gold and Blue 5 (1 June 1905): 8 of fourth-year class officers; Courses of Study Offered by the Latter-day Saints’ University, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1901-1902 (Salt Lake City: Board of Trustees, 1901), [4]; Gold and Blue 2 (June 1902): 5.

[56] Harold H. Jenson, “Tribute to Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 65 (Dec. 1930): 722; also Evan Stephens to Samuel B. Mitton, 2 May 1927, in Bergman, The Children Sang, 246. Jenson’s article described himself as “one of numerous boys Professor Stephens’ influence and life inspired to greater ambition.” Born in 1895, Jenson expressed regret in this article that as a teenager he did not accept Evan’s invitation to leave his family and move in with the musician. Apparently he declined that invitation at age fourteen, shortly before Thomas S. Thomas became Evan’s next live-in companion in 1909.

[57] Evan Stephens, Noel S. Pratt, and Sarah Daniels were among the LOS passengers on Republic, 17 July 1907, in LDS British Emigration Ship Registers (1901-13), p. 295 and (1905-1909), unpaged, LDS Family History Library. Bergman, The Children Sang, 180, described Noel as “one of the Professor’s Boys,’” and also examined the LDS passenger list for this 1907 trip (210). However, German did not mention that Noel was listed as accompanying Evan and Sarah on this voyage.

[58] Salt Lake City Directory, 1906 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1906), 727; Salt Lake City Directory, 1907 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1907), 857 (Noel S. Pratt “bds 750 Ashton av.”), 48 (“ASHTON AVE—runs east from 7th to 9th East; 2 blocks south of 12th South”), 1004 (Evan Stephens “res State 1 n of 12th South); “Singers Will Leave Tonight: Two Hundred Members of Tabernacle Choir Ready for Trip to Seattle,” Deseret Evening News, 21 Aug. 1909, 1; Salt Lake City Directory, 1923 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1923), 770. LDS Ancestral File for Noel S. Pratt shows an undated divorce for his recent marriage, although there is no record of the divorce in Salt Lake County. He died only four years after his marriage.

[59] “THE BEAUTIFUL LAKE MADE BY ‘EVAN BACH’ [Evan Stephens],” Children’s Friend 18 (Nov. 1919): [428]; “Evan Bach: A True Story for Little Folk, by a Pioneer,” Children’s Friend 18 (Dec. 1919): 473.

[60] Entries for Thomas Thomas [Jr.] (b. 10 July 1891) in St. John Ward, Malad Stake, Record of Members (1873-1901), 36, 62; Thomas S. Thomas, Sr. (b. 1864), in LDS Ancestral File, and entries for Evan Stephens and Thomas S. Thomas in LDS church census for 1914, all in LDS Family History Library; Salt Lake City Directory, 1909 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polke & Co., 1909), 1038, 1076; “Singers Will Leave Tonight: Two Hundred Members of Tabernacle Choir Ready for Trip to Seattle,” Deseret Evening News, 21 Aug. 1909, 1. For Thomas’s inactivity in the LDS church, the church census for 1914 showed that twenty-three-year-old Thomas was still unordained.

[61] Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 65 (Dec. 1930): 720; Bergman, The Children Sang, 179-82. Evan’s housekeeper and grand-niece, Sarah Mary Daniels, joined the LDS church after his death. She had herself sealed to him by proxy on 5 November 1931. See Kennedy, “Precious Moments With Evan Stephens,” 28; Bergman, The Children Sang, 189. Kennedy mistakenly identified her as Evan’s cousin.

[62] Jenson, “Tribute to Evan Stephens,” 722; The S Book: Commencement Number (Salt Lake City: Associated Students for Latter-day Saints’ University, 1914), 12-14, 38, for photographs of Thomas. However, Stephens was no longer an instructor at the LDS high school when Thomas was a student there. See “Teachers Who Have Taught At the School,” in John Henry Evans, “An Historical Sketch of the Latter-day Saints’ University,” unnumbered page, typescript dated Nov. 1913, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

[63] Salt Lake City Directory, 1915 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1915), 966; Salt Lake City Directory, 1916 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1916), 832.

[64] Thomas S. Thomas was listed in “Tabernacle Choir In Readiness for Tour of Eastern States,” Deseret Evening News, 21 Oct. 1911, III, 1, 19, but deleted in [George D. Pyper,] “Six Thousand Miles With the ‘Mormon’ Tabernacle Choir: Impressions of the Manager,” Improvement Era 47 (Mar. 1912): 132-33; The S Book: Commencement Number (Salt Lake City: Associated Students of the Latter-day Saints University, 1914), 38.

[65] “Before Justice Pyper,” Deseret Evening News, 14 Jan. 1887, [3]; “PAYING THE PYPER: The Awful Accusation Against the Boys,” Salt Lake Tribune, 15 Jan. 1887, [4]; also discussion in Quinn, Same-sex Dynamics among Nineteenth-century Americans.

[66] Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 66 (Mar. 1931): 133; also Stephens to Samuel B. Mitton, 28 July 1916, in Bergman, The Children Sang, 228; telephone statement to me on 14 September 1993 by Alumni Office of Columbia University’s School of Medicine regarding the enrollment of Thomas S. Thomas in 1916. Evan’s autobiography claimed that he resigned in 1914, but his resignation occurred in 1916. See “Evan Stephens Resigns Leadership of Choir; Prof. A.C. Lund of B.Y.U. Offered Position,” Deseret Evening News, 27 July 1916, 1-2.

[67] his could be disputed, since Anthon H. Lund’s diary recorded on 13 July 1916 that the First Presidency and apostles decided to release Stephens as director of the Tabernacle Choir. Lund worried on 20 July that “Bro Stephens will take this release very hard.” Instead, he recorded on25 July that Stephens “seemed to feel alright” (Lund diary, as quoted in Bergman, The Children Sang, 13-14). On the other hand, in the same letter in which Stephens acknowledged that he was personally offended that a “committee recommended my release,” he privately confided that he had actually “deserted his job” (Bergman, The Children Sang, 239). I believe the resolution of this apparent contradiction is that Stephens resented the LDS hierarchy’s decision to release him, yet he had already planned to resign or ask for a leave of absence so he could move with Thomas to New York. Michael Hicks, Mormonism and Music: A History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989), 157, described the conductor’s abrasive relations with the LDS hierarchy which led to this forced resignation. However, there is no indication that LDS leaders were concerned about Stephens’s relationships with young men.

[68] “Salt Lakers in Gotham,” Deseret Evening News, 7 Oct. 1916, Sec. 2: 7; entry for Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in Trow General Directory of New York City, Embracing the Boroughs of Manhattan and The Bronx, 1916 (New York: R.L. Polk & Co., 1916), 2047.

[69] George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books/HarperCollins, 1994), 217, 428n24, for a raid report dated 24 October 1916. The well-known Ariston homosexual bathhouse was located on Broadway and Fifty-fifth Street, only a few blocks from the hotel where Stephens and his boy-chum were staying. However, Chauncey doubts (216) that “the Ariston continued to be a homosexual rendezvous after being raided [in 1903], given the notoriety of the trials and the severity of the sentences imposed on the patrons.”

[70] “Stephens Writes of Musical Events in Gay New York,” Deseret Evening News, 11 Nov. 1916, II, 3. For “gay boy” as American slang by 1903 for “a man who is homosexual,” see J.E. Lighter, ed., Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang, 3 vols. (New York: Random House, 1994-96), 1:872. For homosexual “cruising” in Central Park since the 1890s, see Chauncey, Gay New York, 98, 182, 423n58, and 44ln50, for “cruising” as a term used by nineteenth-century prostitutes (also Lighter, Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang, 1:531).

[71] “Prof. Stephens Enlists As a Food Producer,” Deseret Evening News, 21 Apr. 1917, II, 6. For the program, see “PROF. EVAN STEPHENS, Who Will be Tendered a Monster Farewell Testimonial at the Tabernacle, Friday, April 6th,” Deseret Evening News, 31 Mar. 1917, II, 5; Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 66 (Mar. 1931): 133; Bergman, The Children Sang, 217-18. “Salt Lakers in Gotham,” Deseret Evening News, 10 Mar. 1917, II, 7, reported that the two “well known Utah boys, Frank Spencer . . . and Tom Thomas, nephew of Prof. Evan Stephens,” were still living together with six other students a few blocks from Columbia’s medical school.

[72] U.S. 1920 Census of New York County, New York, enumeration district 802 (enumerated in Jan. 1920), sheet 1, line 39.

[73] Lyrics of a 1914 song, quoted in Steven Watson, Strange Bedfellows: The First American Avant-Garde (New York: Abbeville Press, 1991), 114.

[74] Colin A. Scott, “Sex and Art,” American Journal of Psychology 7 (Jan. 1896): 216; Havelock Ellis, Sexual Inversion, vol. 2 of his Studies in the Psychology of Sex (Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Co., 1915), 299; Earl Lind, pseud., Autobiography of an Androgyne (New York: The Medico-Legal Journal, 1918; New York: Arno Press/New York Times, 1975 reprint), 7, 77-78, 155-56, 189; Jonathan Ned Katz, ed., Gay/Lesbian Almanac: A New Documentary (New York: Harper & Row, 1983), 235; Chauncy, Gay New York, 15, 190, 228; Lighter, Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang, 1:718.

[75] Chauncy, Gay New York, 235-36, 291, and 431n28, for the investigator’s quote.

[76] “Queen” was slang for male homosexual by the 1920s. See Chauncey, Gay New York, 101; list of homosexual slang in Aaron J. Rosanoff, Manual of Psychiatry, 6th ed. (New York: Wiley, 1927), as quoted in Katz, Gay/Lesbian Almanac, 439. However, there is no published verification that “queen” had this meaning as early as the 1914 usage of “Queener” in the LDS high school’s yearbook. Nevertheless, Quinn, Same-sex Dynamics among Nineteenth-century Americans, has verified other examples where the historical citations in slang dictionaries are decades after Mormon and Utah usage (as sexual terms) of such phrases as “sleeping with” and “monkey with.”

[77] Thomas S. Thomas does not appear as a student in Trow General Directory of New York City, Embracing the Boroughs of Manhattan and The Bronx, 1916 (New York: R.L. Polk & Co., 1916), 1660; Trow General Directory of New York City . . . 1917, 1915; Trow General Directory of New York City . . . 1918-1919, 1874-75; Trow General Directory of New York City . . . 1920-1921, 1783-84. Although the U.S. 1920 Census showed his residence address, Thomas apparently withheld that information from the city directory.

[78] Evan Stephens, “The Life Story of Evan Stephens,” Juvenile Instructor 66 (Mar. 1931): 133. Stephens erroneously dated this as occurring in 1914. See also January 1920 U.S. Census of New York City, New York, for Thomas S. Thomas and wife Priscilla in New York City; American Medical Directory, 1940 (Chicago: American Medical Association, 1940), 1126, for Thomas Stephens Thomas, Jr., graduate of Columbia University School of Physicians and Surgeons, and practicing in Morristown, Morris County, New Jersey; “Dr. T.S. Thomas Dies at 78 at Memorial,” Morris County’s Daily Record (22 July 1969): 2.

[79] Kathryn Fairbanks Kirk, ed., The Fairbanks Family in the West: Four Generations (Salt Lake City: Paragon Press, 1983), 318; Salt Lake City Directory, 1917 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1917), 301, for Ortho Fairbanks at 1111 Whitlock Avenue; Salt Lke City Directory, 1919 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1919), 35, £or “WHITLOCK AV {Highland Pk)”; Ortho Fairbanks (b. 29 Sept. 1887) in LDS Ancestral File; Salt Lake City Directory, 1923 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1923), 322; and Evan Stephens holographic Last Will and Testament, dated 9 Nov. 1927, Salt Lake County Clerk, Probated Will #16540, p. 1, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, for Stephens’s ownership of the Highland Park properties, and p. 3 for Ortho Fairbanks as one of the persons to receive “a memento of my regards.”

[80] U.S. 1920 Census for Salt Lake City, Utah, enumeration district 88, sheet 12; and comparison of city directory listings with the names of all males mentioned in the last will and testament of Evan Stephens.

[81] “THE BEAUTIFUL LAKE MADE BY ‘EVAN BACH’ [Evan Stephens]” Children’s Friend 18 (Nov. 1919): [428]; “Evan Bach: A True Story for Little Folk, by a Pioneer,” Children’s Friend 18 (Dec. 1919): 473.

[82] “Los Angeles Entertains Veteran Composer: Prof Evan Stephens Guest of Musical Organization on Coast-A Most Enjoyable Occasion,” Deseret Evening News, 3 Feb. 1923, ill, 6; The S Book of 1924: The Annual of the Latter-day Saints High School (Salt Lake City: Associated Students of the Latter-day Saints High School, 1924), 106, 120; also, Bergman, The Children Sang, 222-23; John Wallace Packham (b. 28 Dec. 1904; d. in 1972) in LDS Ancestral Pile. Packham turned eighteen in the middle of his trip with Stephens.

[83] Salt Lake City Directory, 1924 (Salt Lake City: R.L. Polk & Co., 1924), 741, 927; Evan Stephens to Samuel B. Mitton, 20 July 1924, in Bergman, The Children Sang, 242.

[84] Salt Lake City Directory, 1926, 1003, 1035, 1443, Salt Lake City Directory, 1927, 424, 1044, 1495, Salt Lake City Directory, 1928, 1041, 1534, Salt Lake City Directory, 1929, 151, 1562; Salt Lake City Directory, 1930, 702, 1609 (all published in Salt Lake City by RL. Polk & Co.); LDS Ancestral File for occupants.

[85] “Evan Stephens’ Treasures Divided,” Salt Lake Telegram, 9 Nov. 1930, II, 1; also Bergman, The Children Sang, 214, 216; LDS Ancestral File for John Wallace Packham (b. 28 Dec. 1904), and his obituary in Salt Lake Tribune, 17 Sept. 1972, E-19.

[86] Samuel B. Mitton diary, 27 Oct 1930, quoted in Lindblad, Biography of Samuel Bailey Mitton, 295. Despite Evan’s expressions of love for Mitton in correspondence as late as 1924, Stephens left Mitton out of his will in 1927. The reasons for that omission are presently unknown, but it must have been a surprise for Mitton when he learned this fact after Evan’s will was probated. Mitton and his wife had continued visiting Stephens up through the composer’s final illness, and Mitton’s diary entry showed the depth of the married man’s love for Evan. Despite full access to his diaries, Mitton’s biographer made no reference to his exclusion from the will that remembered all of Evan’s other “boy-chums” and no mention of Mitton’s reaction to that omission. Either Mitton himself chose not to comment, or his biographer chose not to tarnish his narrative of the loving relationship between Mitton and Stephens.

[87] Evan Stephens holographic Last Will and Testament, dated 9 Nov. 1927, 1, 3.

[88] Evan Stephens, “Evan Stephens’ Promotion. As told by Himself,” Children’s Friend 19 (Mar. 1920): 96; Bergman, The Children Sang, 65.

[89] Thomas S. Thomas was the only light-blond boy-chum of Stephens as pictured in Children’s Friend 18 (Nov. 1919): [428], and described in Jenson, “Tribute to Evan Stephens,” 722. Photographs of his seven ”brunette” boy-chums (at least one of whom may have been dark-blond as a younger man) are John J. Ward in Children’s Friend 18 (Oct. 1919): 388; Samuel B. Mitton opposite p. 6 in Lindblad, Biography of Samuel Bailey Mittan; Horace S. Ensign in Photo 4273, Item #1, LDS archives; Willard A. Christopherson in Photo 1700-3781, LDS archives; Noel S. Pratt in Bergman, The Children Sang, 181; Ortho Fairbanks in Kirk, Fairbanks Family in the West, 239; J. Wallace Packham in Deseret Evening News, 3 Feb. 1923, ill, 6.

[90] Evan Stephens, “Little Life Experiences,” Children’s Friend 19 (June 1920): 228.

[91] John S. Farmer and W.E. Henley, Slang and Its Analogues, 7 vols. (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1890-1904), 4 (1896): 90; Eric Partridge, A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English . . . , 8th ed., Paul Beale, ed. (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984), 638.

[92] “Stephens’ Day at School,” The Gold and Blue 3 (14 Jan. 1903): 5. Although some readers might question whether LDS student-editors would knowingly print a sexual message of this kind, even more explicitly sexual items appeared in the student-edited publications of Brigham Young University. For example, the student-editors included an obviously phallic cartoon in BYU’s 1924 yearbook which showed a man wearing a long curved sword, the tip of which had been redrawn as the head of a penis. The caption read: “His Master’s Vice,” a multiple play on words, including masturbate and “secret vice,” a euphemism for masturbation. See Banyan, 1924, 227; also Gary James Bergera and Ronald Priddis, Brigham Young University A House of Faith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1985), 100-103, 255-57.

[93] The Gold and Blue 2 (1 Mar. 1902): 11; Salt Lake City Directory, 1908 (Salt Lake City: R. L. Polk & Co., 1908), 83; LDS Ancestral File for Louis Casper Lambert Shaw, Jr. (b. 17 May 1884); and extended discussion in Quinn, Same-sex Dynamics among Nineteenth-century Americans. However, neither Shaw nor any other young man moved in with Stephens for more than a year after January 1903, and in 1904 Shaw’s fellow student Noel Pratt began living with the music director.

[94] Evan Stephens, “Going Home To Willard,” Improvement Era 19 (Oct. 1916): 1093.